In May 2013, I traveled to Palestine for six months to collect data for a research project that examines the cultural and visual productions of natalist images, including pregnancy and birth. During the time I spent traveling throughout the West Bank and Israel, I took account of the various modes of (re)production of Palestinian women’s bodies. I am interested in asking first, what do cultural and visual artifacts of pregnancy and birth indicate about the materialities of occupation and second, how do Palestinian women negotiate, respond to and challenge such images? One particularly graphic example I examine in my work is a series of t-shirts produced by Israeli battalion members with images of pregnant Palestinian women carrying captions like “One Shot, Two Kills,” “Better Use Durex,” and “Bet You Got Raped.”(1) First uncovered in 2009 by Uri Blau in Ha’artez, the shirts serve as a reflection on how Palestinian women’s bodies become literal and figurative targets. I argue that such cultural reproductions of violence become mediums where militarization is normalized. Pregnancy, from the position of the military soldier, becomes a literal target whereby deliberate violence against one Palestinian woman yields the death of many more Palestinians to come.

Figure 1: Israeli Soldiers’ T-Shirts

Source: http://www.ifamericansknew.org/cur_sit/deadbabies.html

My research in Palestine documented the various ways in which all Palestinian bodies, male and female, are subject to and targeted by the occupying state. In this short piece, I will focus on how gender and occupation intersect in men’s access to care. As a feminist researcher whose research has focused on Palestinian women’s bodies, I am taking this opportunity to realign feminist practice to examine the ways in which all bodies are subject to the intersections of gender, race, class and power. Finally, I will conclude with some reflections on how the current Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement is one means of addressing the forms of power exercised over Palestinian bodies living under occupation.

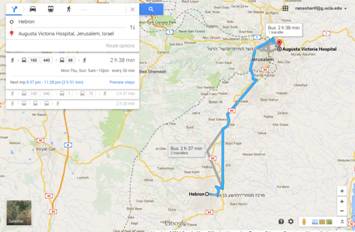

In the space below I will be drawing on participatory observations, specifically moderate participatory observations based on research conducted in the West Bank. The data comes from my own personal writings, observations and participation during my time in the region. I traveled to the West Bank, Israel and Jordan in May of 2013 for six months where I conducted my research. On several occasions during my time in Palestine and Israel, I accompanied bus-rides that transported patients with chronic illnesses such as kidney disease, cancer and/or type I diabetes from the southern parts of the West Bank to the Augusta Victoria Hospital located on the southern side of Mount Scopus in West Jerusalem [Figure 2].

Figure 2: Journey to Augusta Victoria Hospital

Source: Google Maps

The discussion below chronicles the journey undertaken by Palestinian sick bodies to receive life-saving treatment. In what follows, I will be meditating on what such journeys mean for Palestinian (sick) bodies within the context of legal approval for care. Drawing on my own personal accounts and online sources, I hope to illuminate the contours of medical attention for bodies rendered invisible to care. Conceptually, I build on Achille Mbembe’s use of “necropower”(2) to elucidate the framing of bodies in Palestine.

Permission Granted:

Despite the fact that I was really sick, it took a whole day to get the papers from the Israeli authorities for my transfer. At nine o’clock the next morning, we arrived in a Palestine Red Crescent Society ambulance at one of the checkpoints outside Jerusalem. The soldiers stopped us. I heard the driver talking to them, but I didn’t understand what the problem was. I was lying in the ambulance, feeling totally helpless. I, an old man, was seeking medical treatment and it seemed no one was helping me. One and a half hours later, I was finally transferred to the ambulance that had come from Jerusalem to take me to the hospital. (3)Abu Abed’s story is just one of many examples of how Palestinian bodies are exposed to the Israeli state by their pursuit of medical attention. While the ride-alongs I participated in were coordinated by the Augusta Victoria Hospital, each patient was required to obtain their own legal documentation allowing them to receive treatment, and thus access Israeli routes and entry into West Jerusalem. The permits were given at one to three month increments, and appropriate documentation would have to be produced each time a permit application was submitted by or on behalf of a patient.

Abu Abed, 74, from Hebron

The Road Traveled:

Karim and Tariq,(4) ages 16 and 24, are brothers from Hebron. Both Karim and Tariq suffer from a disease caused by a spontaneous gene mutation called autosomal recessive polycistic kidney disease (ARPKD), whereby cyst-like sacs develop on the kidneys and can (and do) accumulate on other organs as well. Due to the severity of their disease, the brothers must undergo dialysis treatment every other day to ensure that their blood rids itself of potentially life-threatening toxins. Both students, Karim in high school and Tariq a fourth-year undergraduate student at the Palestinian Polytechnic University in Hebron, are required to leave their studies and life every other day for medical treatment at Augusta Victoria Hospital in West Jerusalem.

Once I arrived and settled in, I asked Karim and Tariq if I would be able to accompany them on their treatment trip. After making arrangements with the bus driver, they asked me to join. As a United States citizen, I am not required to apply for a permit to enter West Jerusalem. By virtue of my American passport, I am automatically granted access to essentially all of Palestine, including the West Bank and 1948 Palestine, or what is known today as Israel. As a result, the coordinator and bus driver knew I would not pose a problem to their passing through any of the checkpoints and/or barriers they would inevitably encounter.

As seen in Figure 2, according to Google processing time, the route between Hebron and the Augusta Victoria Hospital takes at least two and a half hours, with one transfer. Since the bus we traveled to the hospital in was commissioned for the purpose of transporting patients, no transfers were required, but multiple stops added additional travel time. Karim and Tariq make this trek at least three times a week, more if necessary.It was a Wednesday morning. Karim and Tariq had given me instructions on where to stand on the main route out of Hebron and into Halhul so that I might catch the bus. Their sister, Nuha, joined them.(5) It was 8:30 am when I saw the bus come up the main route. I could see Karim and Tariq standing near the front of the bus, motioning the driver to stop. The bus stopped, I mounted, and we drove off.

The bus was full. People, old, young, infants were dispersed and fortunately they had saved a spot next to Nuha. I sat down and was instantaneously overwhelmed at the sight and sounds of the many bodies—I could not easily distinguish who was sick and who was an escort. Although, I would later figure out that many of those receiving dialysis treatments, like Karim and Tariq, had (creatively) wrapped their forearm where the machine’s tubing attaches. Karim always had his wrapped with a different colored bandana; on this day it was red. Tariq never actually wrapped his forearm, but did wear long sleeve button-ups where he would cover up his left forearm, where the machine’s tubes were inserted.

Hebron was the first major stop, and where a majority of the patients from the southern part of the West Bank came from. We continued north towards Jerusalem on the main highway, and made stops in Tar’umia, the Dheisheh Refugee Camp, and Bethlehem. I had already thought it was pretty crowded when I got on, so was surprised to see how many more [sick] bodies boarded.

Up until that moment, I was too overwhelmed by the thought of the many sick bodies, old and young, crying babies, and noises to notice that there was something wrong. We were approaching the Gilo checkpoint, I think is its name. Gilo is the main checkpoint between the West Bank and Israel. It’s basically the last stop before the patients are taken to the hospital.

[…]

Just before the checkpoint, in Bethlehem, the driver stopped the bus and parked it. He left the bus and sat on the sidewalk, where he began to smoke, and quickly a flood of men from the bus surrounded him. Hands up in the air, people speaking loudly, and the driver visibly distraught. I had no idea what was going on. I just looked, watched and hoped not to get in the way… At this point, the time was approaching 10:30am. All the treatments begin at 11am. Tariq came up and explained to us that for each sick patient, there should be only one escort. The bus was crowded because some had brought more than one person with them.

[…]

We sat there, the time ticked and I remember thinking naively to myself, “what, is he really stopping for a cigarette break?” After a few moments, it seemed that there was some consensus. [Karim and Tariq] approached the window where we were sitting and they quickly motioned to their sister and I to get off the bus. I remember thinking: “um… you guys have dialysis, where are we going? No time to sight-see in Bethlehem.” More naïve thinking.

[…]

We got off the bus. Their sister and I, along with two other young men under thirty who had been outside talking to the driver and an elderly man in his sixties stood in the sun as the bus drove off. It was agreed that rather than us staying on the bus, we would continue the trek to the hospital on our own to offset the overcrowding. The eight of us walked up and down the streets of Bethlehem leading to the checkpoint. The two other young men along with the elderly man were receiving chemotherapy treatment. The elderly man, Abu Nidal, has cancer of the brain. As he recounted his story to us and we approached Gilo, I could not even begin to make sense of this particular time/space formation. After sharing his condition, Abu Nidal said in Arabic, “I will walk and die in my land, they do this to scare us, Allah is bigger than sickness [even death], they will see.”

We arrived at Gilo. They produced their permits allowing them to travel into Israel and I showed my US passport. On the other side we took two other modes of transportation to get to Mount Scopus….Karim was late to his dialysis. Since he has a more aggressive form of PKD he has to be hooked up longer… Tariq took us to the courtyard where we purchased some drinks and his sister and I sat in the courtyard while he went to his treatment.(6)

When considering the “legality” of this experience, on paper it may seem like all formalities are in place: permits to travel, check, bus to travel to desired location, check—not to mention that the bus and its driver need their own approval and permits, nonetheless, check—access for loved ones or escorts, check. In fact, in an article published recently by an Israeli online news source, Aryeh Savir suggests that the number reflected in the title indicates “a dramatic increase” in the number of “Judea and Samaria” Arabs (not Palestinians) receiving treatment in Israeli facilities.(7) Ostensibly, there is much to be celebrated in the overwhelming generosity of the Israeli state in “taking care” of Palestinians from the other side. While Savir suggests that the number of Palestinians receiving care in Israeli hospitals increased dramatically, Saree Makdisi offers a counter-narrative, indicating that due to the separation wall partitioning the West Bank from Israel, specifically Jerusalem from its Palestinian communities, the number of Palestinians living in the West Bank and Gaza who received care in one of the six Palestinian hospitals in Jerusalem decreased by fifty percent between 2002 and 2003.(8) In addition, Augusta Victoria Hospital, where Abu Nidal, Karim and Tariq receive treatment, “registered a one-third drop in its patient load once tightened Israeli controls over Palestinian access to East Jerusalem went into effect.”(9) Juxtaposing Savir’s rhetoric against my observations and existing literature, the facts of gaining access to medical attention challenge the legal premise that care for chronic illness in Palestine is made available. In my summation, it is not enough to suggest that Palestinians are getting treated in Israel or have access to do so without exploring more concretely the processes that entails.

As I watched Abu Nidal, who receives chemotherapy at Augusta Victoria, walking up and down the cobble-stone roads of Bethlehem towards the Gilo checkpoint, I had a visceral reaction. I recall his bald scalp exposing the many scars from surgeries inflicted on him over time to treat his disease. I remember feeling disgusted. Abu Nidal’s life hinges on a permit that must be renewed every three months. Abu Nidal is, however, aware of his location in the necropolitical web created by life under military occupation. His life and death are intimately framed by the material realities of life under occupation. His having to take a two hour bus-ride, having to get off due to overcrowding, having to walk through a city and through a checkpoint, having to produce necessary legal documents and continue to his treatment center by taking two additional modes of transportation on the other side of the Gilo checkpoint was not an illegal infringement of his rights; on the contrary, these are formalities that the sovereign power deploys to maintain and ensure its security and sovereignty. In accessing their medical attention, Abu Nidal, Tariq, and Karim, among the many others, occupy a singular state of exception, where their (material) bodies are always subject to what Achille Mbembe calls the sovereign’s territorialization, in which the occupied subject is constantly and consistently subject to “new set[s] of social and spatial relations.”(10) For Palestinians, who must live out their everyday existence under such circumstances, their material and temporal landscapes must quickly adapt to account for the consistent inconsistencies they face. The boundaries of everyday life are rendered vulnerable to the state’s contortions, while simultaneously needing to be stitched together for the sake of accomplishing the most mundane activities.(11) All episodic flares of trauma are instantaneously absorbed and kneaded into the structures that produce them, ultimately acting as silent killers.

For chronically ill Palestinians, the difficulty of navigating such a fabric of violence is exacerbated by the sheer realities of their disease. Abu Nidal, an elderly man with brain cancer, got off a bus and continued his route by foot. In an attempt to “save time” and offer a quick fix to the over-crowdedness of the bus, his illness took second place to alleviating the material consequences of time/space distortions created by the occupation. However, for how long can he persist? How much longer will such solutions hold when one is suffering from terminal brain cancer? Livia Wick’s work further defines the dynamics of closures and waiting in the West Bank. According to Wick, waiting as a result of closures, “seems to whisper itself in and out of Palestinian history. Its everyday oppression produces uncertainty and insecurity.”(12) Similarly, Julie Peteet has brought into focus the ways in which Israeli existence is contingent upon the “stealing” of Palestinian time.(13) Loss of time, checkpoints, closures and waiting constitute the fabric of everyday life. The exceptional nature of chronic illness is made secondary when the demands of navigating an occupied time and space must take priority: someone or something has to give when a bus full of sick bodies is waiting; permits need to be filed for those seeking treatment and their loved ones, regardless of the nature of the illness.

In 2010, ‘Ala’-al-Din Taslaq of Nablus submitted an affidavit to Al-Haq, a Palestinian human rights organization servicing the occupied Palestinian territories, requesting their assistance in gaining access to medical attention in Israel. In 2009, Mr. Taslaq was diagnosed with colon cancer and was subsequently transferred to Augusta Victoria to receive radiation treatment, which is not available in the West Bank. In order to access the hospital, his wife submitted to the Israeli Health Department of the Civil Administration (HDCA) documentation in support of his application for a permit:

At the [HDCA office in the Huwarra military camp], my wife had to wait for more than three hours in a waiting hall before any [officer] would interview her. Later, an [officer] interviewed my wife for a period of less than one hour and told her that the [HDCA] refused to issue a permit for me on security grounds. My wife presented all the medical reports, which confirmed my need of medical attention at the said hospital, and insisted that she receive a permit for me. At the end of the interview the DCO officer gave my wife a permit, which was valid for one month.(14)While the legal frameworks are instituted in the West Bank by the Israeli military unit, Coordination of Government Activities in the Territories (COGAT), HDCA controls the procedural formalities for seeking such permits. In reality, a colon cancer patient is subjected to these legal frameworks each month, when only given a one-month permit. While it may not seem like too much of a problem to return, the hours spent waiting in line, filing forms, and ultimately knowing one’s life is in the hands an HDCA officer, exacerbate the already trying condition of suffering from a (potentially terminal) illness. For three months, Mr. Taslaq’s wife continued to reapply for permission to access Augusta Victoria, and was given one-month permits. In December of 2010 Mr. Taslaq had surgery to remove a tumor and had an incision made for excretion. In February 2011, he had a follow-up appointment in order to continue with his treatment. His wife again gathered reports, requested documentation from the hospital and submitted the necessary papers in support of the permit. At this point, the HDCA added an additional level to the permit-seeking formality: a Palestinian office was instated, where permits would first go through the Palestinian office and then be transported by the Palestinian office to the HDCA. Mr. Taslaq accounts:

The Palestinian [office] handed the application over to the Israeli [HDCA]. Upon reporting to the Palestinian [office] on the second day, my wife was told that the Israeli side was still examining the issue from a security perspective. Therefore, I lost my appointment. Because an alternative treatment is not available in the West Bank hospitals, my health condition has deteriorated.

In the instances outlined in the pages above, the difficulty of accessing care for sick bodies in Palestine is exacerbated by the material consequences of occupation. As Mbembe has suggested, the necropolitical state is invested in contouring not only the parameters of life (biopower(15)) but also, and perhaps more aptly for the actual life of Palestinians, of death. It is as though life is lived on threads. Buying time, navigating space, accessing units, filing forms, waiting in lines, waiting at checkpoints are all manifestations of the lived reality of Palestinian everyday life that are occluded when one considers only the “legal formalities” Israel has put in place, formalities which seem to allow for access to certain spaces for sick bodies, but in fact hinder or deny every attempt to do so.

From my own experiences on the bus rides with Karim and Tariq to Augusta Victoria, supplemented by reading through documented cases and the existing literature on life under military occupation, it becomes evident that the body’s subjection to intimate spaces of violence violates what life as a cohesive entity might mean, not to mention life plagued by illness.

In conclusion, the discussion above merely points out the ways in which bodies, in this case male bodies, are constantly and consistently negotiating life and death as a result of the structures of occupation. As a feminist whose work focuses on women, I feel it is important to address the ways in which both men and women are subjected to the contours of Israeli occupation. As I briefly indicated at the beginning of this essay, women’s bodies have been and continue to be literal and figurative targets of occupation. What I have attempted to highlight in this short essay are the ways in which Palestinian men’s bodies are also punitively targeted. In this way, the vicious realties of everyday life under occupation, from accessing health care to being pregnant, constitute a necropolitics which affects both women and men.

By way of offering some means to combat the severity of everyday life in Palestine, the BDS movement offers a concrete practice rooted in morality and ethics to challenge and change such circumstances. On various university campuses across the U.S. and the U.K., divestment initiatives have focused on social responsibility clauses built into the structures of all universities that hold the institution accountable for where it sends its money. Companies such as Caterpillar, Elbit Systems and Cement Roadstone Holdings are intimately linked with producing and maintaining the structures, checkpoints, blockades, walls, military equipment and buildings of occupation. As feminists have historically critiqued, challenged and fought against systems of power that render bodies accessible to state and intimate violence, BDS offers a possibility to implement such an agenda.

* PhD Candidate in the Department of Gender Studies at the University of California, Los Angeles. Email ranasharif@ucla.edu. Her dissertation research examines cultural and visual (re)productions of pregnancy and birth in the West Bank, Palestine. In her examination she interrogates what such images indicate about everyday life under military occupation while also asking, in what ways do women challenge, resist and produce their own cultural and visual images? I would like to thank co-editors David Lloyd and Brenna Bhandar for their consideration, support and kindness. I am humbled and honored to be sharing my work in this issue amongst the many amazing contributors.

(2) Mbembe, Achille. 2003. “Necropolitics.” Public Culture. 15:1. pp. 11–40.

(3) “I’m old and sick and my family can’t be with me.” http://www.emro.who.int/pse/information-resources/abu-abed.html (consulted March 2, 2014).

(4) Names and details have been changed to ensure the confidentiality and security of the patients with whom I travelled.

(5) Each patient receiving care can have one murafiq or escort to accompany them; each escort must also apply for a permit to enter Israel on the basis of their family’s medical condition. Such documents must also be renewed. For Karim and Tariq, their parents, sister and brother all had permits to accompany them on their treatment trips.

(6) Sharif, Rana. Journal Entry. May 2013.

(7) Savir, Aryeh. “Israel hospitals took care of nearly 220,000 PA Arabs in 2012.” The Jewish Press. July 30, 2013. http://www.jewishpress.com/news/israel-hospitals-took-care-of-nearly-220000-pa-arabs-in-2012/2013/07/30/ (consulted April 26, 2014).

(8) Makdisi, Saree. 2013. “A Racialised Space: The Future of Jerusalem”. In The Failure of the Two-State Solution: The Prospects of One State in the Israel-Palestine Conflict. Hani Faris ed. New York: I.B. Tauris.

(9) Makdisi, “A Racialised Space”, p. 40.

(10) Mbembe, “Necropolitics”.

(11) In the context of the obesity epidemic in the U.S., Lauren Berlant argues that violence is intricately stitched into the fabric of a society; there is no “real” indication of where it ends and/or where it begins. See Berlant Lauren. “Slow Death (Sovereignty, Obesity, Lateral Agency)”. Critical Inquiry. 2007. pp. 754-780.

(12) Wick, Livia. 2011. “The Practice of Waiting under Closure in Palestine”. City and Society. 23:S1. pp. 24-44. p. 34

(13) Peteet, Julie. 2008. “Stealing Time”. Middle East Report. 248:38. pp. 14-15.

(14) Taslaq, ‘Ala’-al-Din. 2010. “Affidavit No. 5345/2010” for Al-Haq. http://www.alhaq.org/10yrs/reports/testimonies/item/488-affidavit-no-5345/2010. Emphasis added.

(15) For more on biopower and the biopolitical state, seeMichel Foucault. 1979. The History of Sexuality: Volume 1 (New York: Random House); Michel Foucault. 1975. Discipline and Punish (New York: Random House).