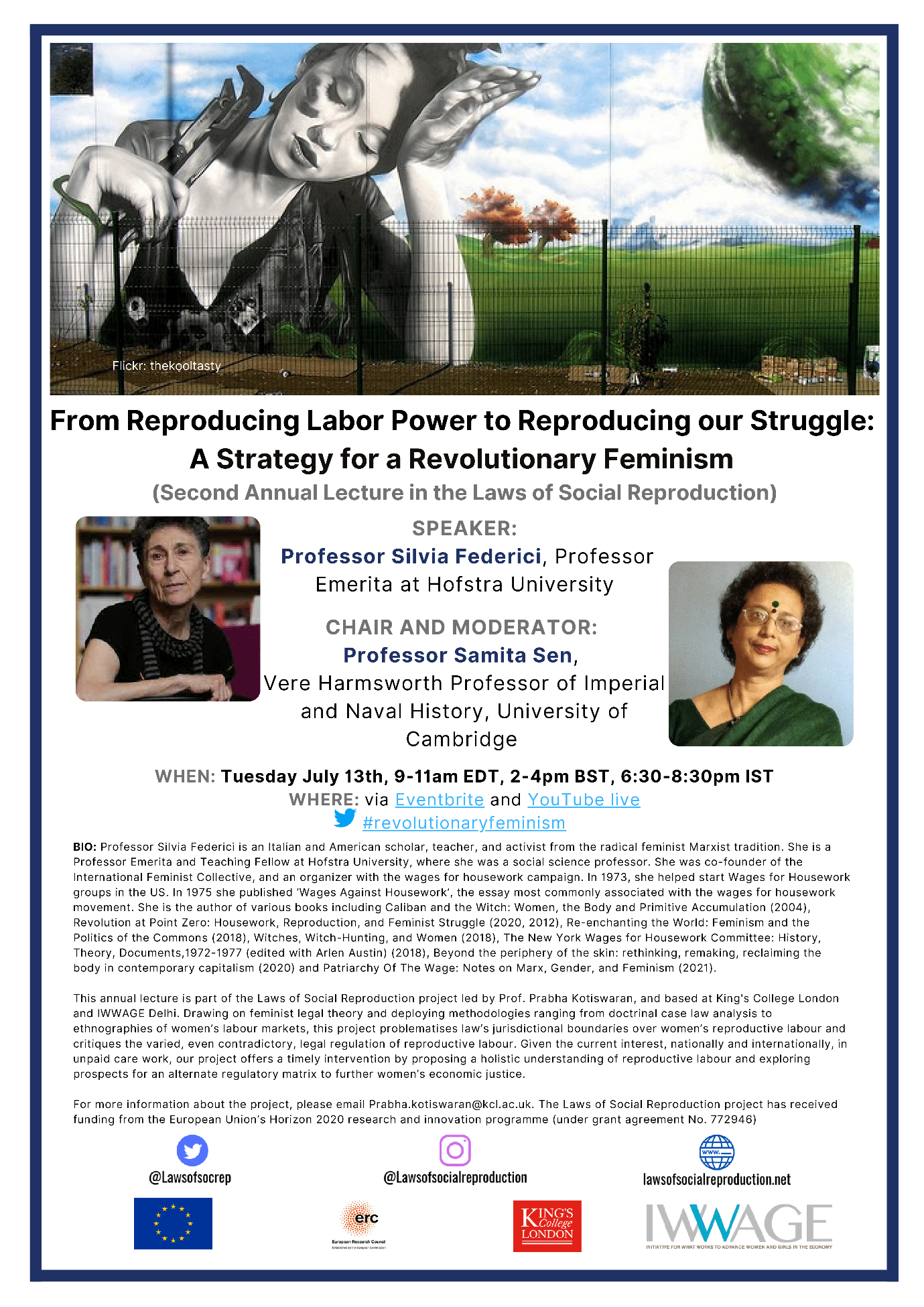

Silvia Federici*

Thank you, thank you Samita Sen and Prabha Kotiswaran for this invitation. And it's a very great pleasure and honor for me to be here with you. And what I try to do in the brief time that I have is to present a few concepts about what I believe has been revolutionary in the feminist program and where I think the feminist program, the feminist struggle, has to go and is already in fact going. The title of my lecture is ‘strategy for revolutionary feminism’. But I want to say first of all, that feminism has already been a Revolutionary War. And, of course, let me be very clear again, I do not refer to the state feminism that was manufactured in the 1970s and 80s and later by the United Nations and several governments whose only purpose was to glorify women’s so-called integration into the global economy, which was a new round of exploitation of women's labour, adding to the exploitation of women's labour in the home. So I want to make very clear that when I speak of feminism, I speak of a very different reality, from the kind of feminism that has been putting on its agenda, equality with men, of course we cannot be against equality with men, but certainly equal with which man? Because the assumption of equality with man is that the male world, the male working class, is not exploited. So obviously those who put on their banner ‘equality with men’ with the heading ‘men’, bearing in mind they mean men of the upper classes, this is the only conclusion one can come to.

But the other feminism has been revolutionary in that it has made visible a whole political terrain of struggle; a whole terrain of exploitation that had been completely ignored by the classical movement of the left: socialist, Marxist, anarchist. And I believe it has uncovered the whole process of reproduction and in this process it has redefined the meaning of work, politics and struggle. It has posed the questions of what is capital exploitation and what is capitalism itself. I think it has been a revolutionary process, a revolutionary contribution. And I must say it is often belittled or forgotten by many of the new theories of social reproduction, and this is why I am particularly concerned, where we are circling that. I think the redefinition of what reproductive work is and what is the specific form of exploitation that women suffer in capitalist society is something that I think is not yet still been completely appreciated. Because this is what has emerged is that we are engaged women traditionally, the majority of women engage in activity, it has a double character with an activity for both that is essential for the reproduction of our life, and therefore is intimately in all its forms involved in the reproduction of life and at the same time continuously captures this thought that finalize, the reproduction of our exploitation to the reproduction of labour power, the workforce etc. That duality, that continuous duality there, has torn women’s lives apart and has also created a continuous daily emotional struggle. Because every time, for example, women have wanted to refuse this work, they've confronted the fact that part of this refusal has appeared as a refusal of relations that tied them to their family, to the people they love, to their children. For the feminist movement to be able to put words to clarify what belongs to capital in a certain way, what in our work, what in this activity has been constructed, has been distorted to benefit capitalist accumulation, to benefit the capitalist organization of work and what we did instead is important, because it is what ties us to the real reproduction of life. I think that to have brought to the surface that contradiction, that contradiction which shapes so much of women’s lives has been a very, very important contribution and it is something that we are continuously dealing with in our lives.

I mean more recently, the call that came from women in Argentina for their reproductive rights, for the women’s strike, brought that contradiction very much to the foreground, showing in fact, women’s refusal to work. Women’s strikes cannot be conceptualized in the way that traditional strikes by the male wage working class have been constructed. Precisely because of their duality; precisely because of their contradiction. There is a tremendous knowledge that I think women have gained as to what is important for our lives and what is not. What aspects of reproductive works should we discard and which ones do we need to transform and revalue? Because I think that one of the dangers in here, I want to come closer to the present, one of the dangers that I think many women, many families have encountered is the pain, the suffering, the exploitation the devaluation of this work. The fact that so much of this work is being done in isolation, in a way that has suffocated our life, has led many women to think: ‘OK, enough, this work we have to do: women’s liberation, women’s emancipation lies completely outside of this work’ right? They dream that if we go outside the home, if we gain a job outside the home, this will in fact open up to us a world of creativity, a world of sociality and in that process, the devaluation of their work happens. And I want to say that in fact one of the tasks, and this is one element of a revolutionary strategy for the feminist movement, is to precisely learn, know to revalue those aspects of reproductive work. Those expert reproductive works that in fact are fundamental to the reproduction of our life, and not to be deluded by the fact that capitalism has penetrated so profoundly in every shape in our life, in the most intimate way to actually discard this work as a whole, and to think that creativity, transformation, liberation lies only outside of the sphere of reproduction. And so in a way, one first element of revolutionary feminist strategies is to reclaim, to regain, to know the importance of the reproduction of life, of reproductive work and reproductive activities. So this is the first thing I would say.

Today, the question of reproduction has come back on the scene in a very explosive way because of the situation that COVID has produced. There are so many women who in the 1980s and 90s had gone to work outside the home and looked for and sometimes gained a certain autonomy through wage-work and they have been brought back to the home. And this in a way seems to me has proven, has demonstrated, the wisdom in a way, of the position that we took in the wages for housework movement of the 1970s which was that we cannot change the condition of women. And by women, I mean women who are not in possession, in control of capital, who have not benefited from the exploitation of other people; women, in the broadest sense of the word, in full awareness of all the differences and the inequalities that exist among women itself, but there is still an element of commonality. The point is that we cannot imagine a process of liberation simply by leaving the so-called home and ignoring the sphere of reproduction. I think it's very important and the events of the last 30-40 years have proven that we in fact are very correct in our understanding. On many different grounds, we've seen, in fact, the majority of women’s work outside the home has not only been a form of liberation, but in most cases it has not even provided a kind of autonomy that was sought for.

For example, in United States today, to a great extent women working outside the home are dependent on loans, loans by pay day companies to actually make do to the end of the month. So, the work outside the home has become accompanied by a massive process of indebtment. Women use the wage to take a loan from one of these companies at an interest rate at times of 50%, which means that they work, work, work in the home, outside the home and yet to pay their loans that will probably follow them - unless we change fundamentally the conditions of our lives - it follows them throughout their lifetime. We have seen also that the majority of the jobs that women acquire outside the home are underpaid and precarious. In most cases, they are an extension of the housework in the home and not jobs that provide a kind of creativity and sociality. Most often they reinforce the kind of isolation that women have suffered in fact in the home. The statistics about women’s health, women’s life expectancy, are in fact, astounding; across the board we've seen, for example, a massive increase of use of tranquillizers, use of antidepressant pills and a decline in life expectancy, all of this and this is before COVID. And now the COVID pandemic has demonstrated that unless we deal with the issue of reproduction - unless we deal with the fact that this society is not taking responsibility for our reproduction - that in fact, the majority of the work, of the reproductive work is still expected of women. That affects the life of the majority of women in every part of the world, whatever else we do, whatever else they do.

I believe that even the old and new discussions and analysis of reproductive work and social reproduction have not come near, and I say it with full knowledge, have not come near to describe what is involved in this work, and particularly what is involved in domestic work. I think it would take the Encyclopedia Britannica to really describe what is the work of reproduction in the life of a woman. Often we speak of childcare; childcare does not even convey what is involved in the process of caring for an infant and caring for a child particularly for the first year of life. And we also forget that for women, in addition to the work of child raising, there is the work of assisting people in their old age, of assisting people through the chronic diseases. This is work that contains so many, so many activities, so many duties, so much emotional stress. I don't think that we have yet found the words to express what is involved in the life of a woman; for example, day after day, year after year, has to take care of a person who is dependent on her for her life because he or she has serious health problems and that work is what is their lifeline. For their parent, for their lover, for their friend. I want to say this because I think that is the actual reality. We say that domestic work, reproductive work, is multitasking, indeed it is really multitasking because it's physical, it's intellectual, is emotional, is psychological and all the work that women do in order to keep the communication in the home; to keep the communication beyond the simple exchange of words, but to actually maintain a process in which people communicate with each other, which is different from speaking to each other. Leopoldina Fortunati has written a very interesting text examining this difference, 1 the fact that we are now more and more speaking with each other in a very instrumental way, but are not communicating, we're not actually speaking to our deepest feelings, to the transformation that we go through our fears, our desires, and about how the new communicative technology, whether it is the computer, the Internet, the phone, the television actually occludes, hides the crisis. A crisis that is rooted in the lack of time, in the lack of energy, because communication is also work, it takes energy to contact really another person. But life is so pressing, it’s so precarious, it's so full of worries that we do not engage any longer in that communication. Although it is women who mostly attempt and strive to keep the communication in the family, and also reconcile all the different crises that can arise.

So the second point I want to make - and it's important that we take it with us as we think about how we change the world – is that in the process of being exploited in a very specific way in the capitalist organization of work we have also acquired a lot of knowledge. Because of the double character of reproductive work, there is also knowledge that we have acquired. There's also knowledge a lot of women have acquired as to what is important about life, what is useful, what it is that gives us life and what it is that kills us. And I think this is a knowledge that women have brought up, bringing it to all the revolutionary movements in which they are involved, the feminist movement, but also the ecological movement. It is not an accident, for instance, that today across the world; from England (I have read articles that women are leading the struggle against fracking in England), to the Amazon. It is women who are really in the front line of the struggle for the defense of the natural environment, the struggle against deforestation, the struggle against monoculture, the struggle for recuperating all the systems of agriculture. They struggle against it - the destruction of mining and petroleum drilling continuously poisoning the water - often having to fight against the men of their community and certainly the man hired by these companies discovering that the destruction of the natural world goes hand in hand with an exacerbation of patriarchal violence. Violence against women increases because mining work is work that brutalizes men. And in many ways, they attempt, as so often men do, to recuperate some sense of life at the expense of women. So, I want to say that today, the feminist movement has a great contribution to make to the construction of a non-capitalist society and the struggle against all forms of oppression, all forms of inequality.

Starting from the perspective of reproduction (and here I want to say something very important, a third point that was brought out very powerfully recently by Veronica Gago, one of the leading voices in the Ni Una Menos movement in Argentina, in her book La Potencia Feminista) we should not look at reproduction as a kind of another economic sector to place side by side with production. We should not base it, like the complementary part of an organization, on work, but we should actually look at reproduction as something, as a broader perspective from which to look at the world, from which to look at struggle, from which to look at revolution that does not separate people’s life into different compartments but actually looks at their lives, wherever they are, whatever they do, from a very holistic viewpoint. So reproduction becomes the biggest category because it says it is the category that allows us to think of the organization of work, the production of social wealth and social change from the point of view of what it is that makes us prosper. What is it that gives us life. What is it that makes lives thrive and what is it that destroys it. So, this is the perspective. And in that sense when we speak of reproduction it is a perspective that we can bring everywhere. Not only in terms of the home or the community, but all the different branches of the service sector or agriculture, a major place of reproduction, but it's a perspective that we should bring also in the so-called world of production. We want to see a world, - and this is a part of what we need to fight for - in which when we take the job outside the home we struggle not only about time; we struggle not only about wages or conditions of work but we struggle also about what is being produced. What is it that is being produced? Is it something that is beneficial to people or are we producing nerve gas? Are we producing bombs, are we producing arms etc? Reproduction is a very broad perspective. It's not just a set, like the commons, of particular activities, it's a principle. It's a conception, of how we look at life; how we look at social relations; how we look at the production of social wealth.

Now, in terms of the strategies of the 1970s we created a movement, a number of us, of Wages for Housework that was very misunderstood, as Prabha and Samita have pointed out. It was really misunderstood as it was understood in a Union framework as if it was part of the union productivity deal. Give us some money and we'll continue doing this work. While for us it had very, very different, finalities. One, first of all, was to make it visible. We thought that demanding a wage would be the most effective way to make visible the capitalist nature of this work, to redefine this work and show how it is directly, intimately involved in the reproduction of the workforce at all its levels. And, of course, also the whole question of sex work. So many feminists have taken a very puritanical position about sex work and have not seen that, because women in capitalism have been traditionally excluded from monetary relations, they have had a very precarious relation to manipulation, so selling our body, whether to industry or in marriage, the possibility of survival, has always been an option and that the kind of work that women have accessed outside the home has been so destructive that often sex work has appeared as the better option. We saw Wages for Housework as bringing out to the surface a whole history of women’s struggle and making visible this work and also - and here I want to make the connection with the present - beginning triggering a process of reappropriation, and undermining the idea that, for example, the welfare position that was in place in the United States, women with younger children receiving some money from the state, that this was charity. Undermining the idea that we were fighting for work. That we were not working already and also presenting the bill to the state. Presenting to the state our bill, saying we have been working for you. Your wealth has been built on the back of our mothers and grandmothers. Clearly more if it is black women or the bill goes back to slavery or women in the colonial world; capitalism has been built on the unpaid labour of women, and we are not fighting for more work. Let's fight first of all to reclaim the wealth that we have produced, in other words, we refuse to say our liberation is fighting for wage labour, that we need to get wage labour in order to be part of the working class or in order to receive some independence.

It seemed to us that we had to deal with that age-old question. The age-old question of the naturalization of domestic work, the naturalization before we could contract. Before we could change our life and our relationship with men, with other people, with capitalism in any other place. This, of course, was a call for not taking work outside the home as we all were working outside the home. There was not even a choice, in the 70s already having a wage job was the minimum not to be completely dependent on a man. But I think it's very important to see today - and this is another point that I want to stress and I hope we can talk about in the discussion- the work that the global movement of domestic workers has brought back at a time when many feminists have forgotten about reproduction. Today everybody speaks of social reproduction but for a long time in the 80s and 90s reproduction kind of vanished except in the context of abortion rights. The global domestic workers movement is very powerful because it brings together the question of sexism and the capitalistic exploitation of female labour with the question of coloniality: most women come from a former colonial world, we could say from the colonial world because colonization is not ended. Globalization is a form of colonization. Colonization is only a changed form. It's like slavery in United States. We still have slavery, except now it's called mass incarceration. It is an organized mass incarceration in the same way coloniality is still a fundamental structural characteristic of capitalist society which is accepted today. Coloniality is organized through the World Bank, the IMF, the structural adjustment programs, all the companies’ extractivism. This is a colonial world. It's still a colonial world. And domestic workers have brought that and the struggle against racism. So their struggle is very rich because it's a movement that fights for the elimination of all restrictions on immigration; an immigration that is being forced by international capitalist politics. So I think that this movement is a movement that has to be at the center of feminist mobilizing - that wherever feminist activism is involved it has to fundamentally support, connect with the struggle of the domestic worker.

Back to the point about wages for housework; it was primarily a movement of reappropriation of the wealth women have produced. And I think the question of reappropriation when we speak of revolutionary feminist strategies is fundamental. We cannot change the world on the basis of a reconstruction, redistribution, reorganization of our power only. Any feminist movement engaging in truly revolutionary transformative strategies has to engage in a process of their reappropriation. Reappropriation of resources, of social wealth, the appropriation of time and space. This means that we have to be present and connect with the whole variety of struggles. The struggle for the reduction of work time, the struggle for the reduction over time is very, very important. I'm going to come back to it. This struggle for the control of space. Housing, urban space, the right to be in the street. For example, one of the responses of women across the world to the crisis of the male wage and to the crisis of traditional forms of work has been to go out en mass in the street in India, throughout Latin America. In Africa already the markets were dominated by women, were a big women’s Common, but now this has expanded, women going into the street, bringing in fact their reproduction into the street. To sell something, some services, snacks, etc. and they face a tremendous amount of violence, violence by the police; violence by shopkeepers who see them as a competition. But at the same time, this is a whole struggle about space. Not the only one, of course. The space about housing and which is a struggle, not only about rents, it is also a struggle for creating housing, forms of housing that do not separate us; that includes communal spaces, the communal areas and spaces in which we can come together, right? So that process of reappropriation of time, space, social resources is fundamental. Equally important - and this is what I've been writing about and continuously learning from the experience of women: the politics of the common, equally important, the construction of the reproductive commons.

By the construction of communitarian and communal collaboratives, cooperative forms of reproduction. And here I am not speaking of utopia. Here, I am speaking of a reality that is already taking place. The great female common of the market; the women occupying the street and struggling, struggling to maintain this space. It's now everywhere and the response has been very important. It's been the response from Africa to Latin America to the United States to the crisis of reproduction that we have faced. The fact that more and more people are being expelled from their ancestral areas, they've been expelled from their land, they've been expelled from their forests, they've been expelled from their population. Women, in particular, have been able to reconstitute in urban spaces and they have been able to reconstitute new forms of life by joining their forces by coming together. By collectively constructing places to live in. Building roads; creating open gardens; creating spaces where they join and have assemblies; and come together to make decisions collectively to decide what is it that we need. The whole assembly movement, for example, that has developed in Latin America from the movement of picketeers. Women have brought their reproduction into the street but also they have reorganized it in a communal way. And in a way that has given them a tremendous strength to confront the state. To put demands to the state. And first of all, not to be separated, not to be destroyed by the crisis that they were meeting. I think that this movement is now very broad and extends from Standing Rock to incredible assemblies of women and people organized by women who defend the waters against the pipeline that poisoned the traditional form of access to water; to Bolivia, to the periphery of Buenos Aires, Mexico. All the places where women have reconstituted this communitarian relation and I think that this is a lesson that that we have to learn from.

Obviously, there are no models; we cannot think of this as a model we're going to explore. Each situation has its own peculiarity. I imagine the construction of commons, rural urban commons in India or in Peru, etc. takes different forms because we have different historical, political trajectories but there are commonalities. The fact is that we need to bring together to unite what capitalism has separated. We need to construct a society in which what capitalism has separated is brought together at all levels. The countryside with the city; production and reproduction and organized in a way that has a primary goal undermining the inequalities that capitalism has planted in our bodies, in the working class, and this is something for me very, very, very central.

From Caliban and the Witch through all my work; we cannot speak of building a society constructed on the principle of commonality and collaboration unless we place, as a central goal, the undermining of racism, colonialism, imperialism. This is in a way a fundamental task of every social movement which wants to create a different society and for the feminist movement as well. But in order to gain the strength to confront the mega capitalist machine and, for example, organized, which I hope we will do, which has been happening but in very sporadic ways; in order to organize the kind of movement that has the power to put an end to the war machine, to the production of arms, to the destruction of countries we have seen one after another, Somalia, Libya, Afghanistan, Iraq, countries being torn apart; we need a feminist movement. We need a feminist mobilization that is able to put an end to this kind of destruction.

We need a feminist mobilization that intervenes to put an end to the fact that now companies, mining companies, oiling companies, fracking, logging can go to any country in the world and destroy the livelihood, destroy the habitat. We need a feminist movement which puts into practice on a mass level what we have learned from the whole history of reproduction about what gives life and what is killing us, but in order to do that, in order to gain the strength, we also have to work at the local level. And to work at the local level to actually create, on a day-to-day basis, different forms of relation, different forms of reproduction.

One of the great revolutionary principles the feminist movement launched, starting from the beginning, from the 70s has been that you cannot change the world unless you change your daily life. It's something that we learn, out of necessity because we discovered that in many cases, if we wanted to go to a demonstration against the war or the student movement etc. we had to fight with people in our family, with our father, with our brother, with our lovers. In other words, that we couldn't really, women have been so dependent, made dependent on men on all levels of our life that the moment we wanted to actually fight against the system, we discovered, we first had to fight the embodiment of patriarchy in our home. For those in our home, in a way, represented the state, because of the power of their wages. Actually, I have written many times that capitalism has delegated to men the power to supervise and control women’s lives. It's never helped to control us directly, they have to, particularly around issues of procreation, reproductive life, etc. But most of the control has been indirectly through men, so this idea you cannot fight, you cannot make a revolution unless you start transforming your everyday life is very powerful. This is why every women’s movement is a movement that has to first confront the question of patriarchy and so change our daily life.

That means many things today and there is now a rich literature if we talk about social reproduction. We have to look, not only at academic theories, but we also have to look at the experience that is coming from so many women, particularly from the global South. For example, if they are fighting against the destruction of a forest, often they have to fight with the men, the men in their community who do not see, who may be interested in the money that a company brings and not have the long-term vision which says once the forest is gone our own life as a community is gone. So the transformation of the daily life, the creation of more connected collaborative forms of reproduction. Breaking down the individualism and the isolation that comes with it, which makes us more vulnerable, which makes it easy to defeat us, to break down; to construct the movement that is political and nevertheless creates effective ties, creates a trust, creates challenges to these old perverse ideologies coming from a capitalist state. They basically tell you ‘be careful with other people’, ‘other people are a threat’, every night on the television, everything is a bombardment about the fact that you turn the corner and somebody is out there to kill you. Regaining not only trust in other people, but the excitement, relearning what a wealth it is to be in a communal relation with other people. Other people are not the threat, but are the enrichment and how much they enrich our life. How much power comes from being engaged in forms of reproduction in which you are not alone, in which you do not confront your pain, your suffering and your crises alone. There is somebody there we know we can share (with) and how your imagination, our imagination of a consciousness expands and we can see different possibilities. The fact is that we can’t actually imagine if we are alone at home, but if we are 20,000 or 10,000 or even 100 in a street or 10 in a park we can actually see other possibilities. This to me is the revolutionary strategy that has to work at different levels. It has to work at a level of the reconstruction, the communal reconstruction of our everyday life, so to gain strength for the process of reappropriation and for the process of mobilization that in fact confronts the state. It confronts the state in its all-lethal power whether it is the police, whether it is the war machine and whether it is an unjust, systematically unjust, institutionally racist organization of the distribution of wealth. I think this is the process, and this is the agenda for revolutionary feminism and the idea fundamentally is that the revolution is not in the future - it is now. The revolution is now. It is not something that we have to look at, to be achieved and it doesn't have to be identified with an immediate change of the whole system. But it begins with the process of transformation in our lives, in our community. And this is where we start. Thank you very much.

1 See Fortunati, L., & Edwards A.P. (2022). Gender and Human-Machine Communication: Where Are We? Human-Machine Communication, 5, 7–47. https://doi.org/10.30658/hmc.5.1