This commentary builds on Lauren Berlant’s affective notion of intimate publics to offer a reparative and melodramatic reading of Thai drag aesthetics in conjunction with the Constitutional Court Ruling No. 20/2564 on same-sex marriage and contemporary constitutionalism more broadly. It explores how drag sentimentality not only disrupts public discourse that perpetuates homophobic and transphobic assumptions but also creates an intimate public space that is both generative and healing for queer communities as they struggle for legal recognition as Thai citizens. This understanding of the intersection between the public and the private is particularly relevant during the contemporary period of democratization in Thailand, where constitutional issues are deeply intertwined with sex, gender, and sexuality.

But how can I call ‘intimate’ a public constituted by strangers who consume common texts and things? By ‘intimate public’ I do not mean a public sphere organized by autobiographical confession and chest-baring, although there is often a significant amount of first-person narrative in an intimate public. What makes a public sphere intimate is an expectation that the consumers of its particular stuff already share a worldview and emotional knowledge that they have derived from a broadly common historical experience.(1)

I remember very well the night I went to watch a drag show at The Stranger Bar in Bangkok with my friends, whom I met in person for the first time in October 2022 after socializing only online during what seemed like a perpetual COVID-19 lockdown. It was also my first time watching a live drag performance. The bar’s atmosphere was vibrant, with loud pop dance music and colourful disco club lights swaying over the bodies of drag artists and audiences from various genders, sexualities, and nationalities, creating a connective assemblage of sensational feelings. The glamorous elevated stage at the front had drag queens performing like the owners of the house, welcoming a packed crowd below. The drag queens displayed their talents by lip-syncing to sensationalist songs, exaggeratedly impersonating iconic divas like Cher and Beyoncé. It all felt incredibly intimate as they were dancing, drinking, and socializing with joyful gesticulations.

It may be counterintuitive to say that drag aesthetics, which cling to traditional heterosexual norms, are capable of both disrupting such norms and providing an intimate space for queer people in constitutionalism. However, the striking and exaggerated audiovisuals of drag performances foster emotional interactions between drag artists and audiences, creating what Lauren Berlant calls an “intimate public”. In The Female Complaint: The Unfinished Business of Sentimentality in American Culture, Berlant uses “intimate publics” to explain sentimentalism in the United States during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, which tended to individualize women’s issues. Berlant articulates that women used sentiments to create intimate publics that engaged those with shared sentiments and historical experiences, thus challenging the dominant gender discourse:

[An] intimate public is an achievement ... provides a complex of consolation, confirmation, discipline, and discussion about how to live as an x ... The intimate public provides anchors for realistic, critical assessment of the way things are and ... enjoying being an x ... This book tracks the ‘bargaining’ with power and desire in which members of intimate publics always seem to be engaging.(2)

I understand that Berlant sees intimate publics as a space for new possibilities of multidirectional interactions. This articulation describes my feelings at The Stranger Bar very well. There I was mesmerized by the harmonious engagement of the audience with the drag artists. In this intimate public space, everyone seemed to temporarily put aside the dominant social script and rather follow the artists’ script through their exaggerated performances, creating collective and affective interactions.(3)

In an issue of Capacious, a journal of affect studies—an emerging field in social sciences and humanities that focuses on emotions, bodies, and subjectivity(4)—Ann Cvetkovich wrote a short piece following Lauren Berlant’s passing in 2021, referencing their writing workshop announcement and underscoring the importance of Berlant’s notion of infrastructure concerning unconventional forms of expressions. The announcement reads:

What do various forms of writing—at the level of both sentence and structure—do to represent, describe, or remediate data or evidence, and how can such work place pressure on conventional models of data and evidence? How can developing a writing practice not only address methodological and intellectual/theoretical questions but make it easier to get work done? We will write periodically throughout the event, by ourselves (with our objects) and collaboratively, with each other.(5)

Cvetkovich and Berlant’s workshop announcement has inspired my project to figure out how we can write and see drag aesthetics as the genre that creates a public space that embraces queer voices. The use of the paper title “Format as Infrastructure” captures how Thai drag aesthetics perform as an alternative format for creating an infrastructure of queer feelings.

For clarity of my articulation, I need to define five key terms: drag sentimentality, intimate publics, social scripts, format, and infrastructure.

(1) “Drag sentimentality” in this essay refers to Berlant’s notion of sentimentality, which unpacks women’s culture expressed in sensationalist literary genres in America. I draw inspiration from this term to explain queer sentimentality in drag aesthetics, which exaggerate dominant gender norms in parodic ways.

(2) “Intimate publics”, as defined by Berlant, refer to the juxtapolitical encounter between the public and the private.

(3) “Social scripts” in this essay refer both to structural social scripts like heteronormativity and interpersonal social scripts, which define drag theatrical scripts in between as counterscripts.

(4) “Format”, inspired by Cvetkovich and Berlant’s workshop announcement, refers to how traditional legal language reinforces the abstraction of the law, while the poetic format of drag creates a more flexible and inclusive infrastructure for expressing queer multiple identities.

(5) “Infrastructure” in this essay draws inspiration from the workshop announcement, which I think plays with the juxtapolitical nature of queer politics in which queer issues are personalized and politicized at the same time. Infrastructure here means the infrastructure of queer feelings which are both intimate and political, as well as the legal infrastructure that helps LGBTQIA+ people actualize their legal relationships, such as marriage. The juxtaposition between these two infrastructures aims to show how they are radically intertwined. The recognition of queer rights is another step towards a country’s democratization, and vice versa

This joyful reading shows the power of artistic performance in creating a queer intimate space that heals and resonates well with Berlant’s concept of intimate publics. Using Berlant’s intimate publics as my main infrastructure for sharing my thoughts and emotions with drag aesthetics,(6) I reflect on my experiences as a queer individual and an audience member of drag performances. This reparative essay juxtaposes Thai drag aesthetics with the dominant legal discourse, as seen in the Court’s ruling on same-sex marriage. I will articulate how drag sentimentality not only subverts static binary divisions between private and public, man and woman, heterosexual and homosexual, and reason and emotions, but also provides a generative force that creates a sense of belonging in the dominant public sphere.

Engaging with drag performances as an audience member makes me feel that these performances affectionately cultivate intimate public spaces filled with queer emotions and sensations. Within these intimate publics, there is a convergence between the high and the low, the sacred and the profane, and heteronormativity and queerness. Through the exaggerated expression of femininity and other forms of personal expression, individuals can freely manifest their chosen identities, experiencing a profound sense of dignity. In interactions with others, these expressions meet with diverse values and emotions, reinforcing the spirit of democracy, where every individual within the social contract is recognized as a citizen. This intersubjective moment between the drag queens and the audience was a powerful demonstration of how strangers could come together, transcending their differences and experiencing the transformative power of drag. At that moment, I truly felt the bridging of people from different backgrounds but with a shared history, which underscores the inclusive and unifying nature of an intimate public empowered by drag sentimentality.

In this essay, I draw further inspiration from Danish Sheikh’s law and theatre paper(7) that employs Eve Sedgwick’s reparative reading, which shifts focus from a paranoid reading of a text’s hidden meanings to its emotional impacts on readers as a way of being generative rather than deconstructive. Sheikh reads a 1934 Indian sodomy trial in tandem with the 2016 theatre performance Queen Size, which displays joyful resistance to the law.

In March 2024, Thailand passed a marriage equality bill, amending the Civil and Commercial Code (CCC). One crucial aspect of the law is the replacement of binary terms like "husband" and "wife" with the gender-neutral term "spouse," and "man" and "woman" with "person". The bill was approved by the Senate on 18 June 2024, making Thailand the first country in Southeast Asia, and the second in Asia after Taiwan, to legally recognize same-sex marriage. It is set to take effect after being published in the Royal Gazette, following a 120-day period.(8)

Reflecting on the journey of the law from the heteronormative ruling by the Constitutional Court in 2021 (see below) to the Bangkok Pride parade themed “The Celebration of Love” on 30 June 2024 to mark the historic moment of legal marriage equality, I, as a queer individual and a legal scholar, see that drag aesthetics are increasingly used in queer movements in Thailand. This is not only to subvert heteronormative norms but also to create an intimate infrastructure of nondominant feelings that remain unseen in the dominant legal discourse.

On the night of Sunday, 28 November 2021, two weeks after the Constitutional Court ruled that section 1448 of the Civil and Commercial Code (CCC) of Thailand, which restricted marriage to being between a biological man and a biological woman, was not unconstitutional,(9) I felt a strong urge to join a vibrant queer protest in the downtown shopping district of Bangkok. Apart from the other technical arguments concerning the substantive rights to marriage and family, one problematic rationale of the judgment that lingers with me until today is the notion that queer couples are unable to establish “deep relationships”. The queer protest I attended embodied the constant struggle for the legal recognition of queer marriage and family rights, demonstrating the vibrant LGBTQIAN+ communities in Thailand, including queer people and allies who demanded changes to section 1448 and other marriage-related sections of the CCC to be more inclusive.(10) I was surrounded by vibrant gatherings of queer creative expressions that made me feel intimate even though I went there alone before meeting up with my nonbinary friend. The street, once full of traffic, was turned into a space for various political campaigns. Many participants were wearing white wedding-inspired aesthetics, probably after the afternoon parade that I sadly did not attend. In this vicinity, there was a booth by iLaw that demanded signatures for a proposed bill to abolish section 112 of the Criminal Code of Thailand, which refers to the lèse-majesté law; the 1908 law that makes it a crime to defame, insult or threaten the monarch of Thailand. In recent decades, this law has been increasingly used to create a chilling effect on progressive political dissidents who seem to defy the status quo. However, most of their expressions are mere exercises of freedom of speech.(11) On the central stage, there were captivating performances by queer individuals, including a group of queer youth from the northeast region of Thailand, who presented their interpretation of traditional songs and dances infused with queer aesthetics. People on the floor conversed with one another, and many danced to the rhythm of the stage, creating mutual interactions in this intimate public space.

I vividly recall a woman dressed in a white top, symbolizing the marriage equality theme, standing on a platform elevated many meters above the ground, challenging the phallocentric space of the shopping district, which can be seen as a place for heteronormative capitalism. This woman wore a gigantic rainbow skirt composed of long individual cloths of various colors, assembled to create a breathtaking visual. With a firm gesticulation, she waved the 2018 Progress Pride Flag, captivating the participants on the ground who looked up, cheering and admiring her performance.

Figure 1 depicts a woman in a wedding gown standing on an elevated platform, each layer of her dress merging seamlessly into a rainbow, waving the pride flag proudly. Copyright © 2021 by Paweenwat Thongprasop. All rights reserved.

In this intimate atmosphere, I had the chance to meet up with my non-binary friend, who had also taken part in the earlier parade. They were beautifully adorned in a white wedding gown and gave me a Pride Flag to wave. I have kept this flag until today.

Figure 2 depicts the rainbow flag that my non-binary friend gave me. The Thai text on the flag reads “marriage equality”. Copyright © 2021 by Paweenwat Thongprasop. All rights reserved.

I was immensely proud to be part of the community and felt an emotional connection to this temporary public space created for queer gatherings. This event showcased the transformative power of art in challenging the prevailing legal discourse around marriage rights and the right to form a family, which traditionally focuses solely on the heterosexual nuclear family model. The protest gained significant public support, with more than 30,000 signatories gathered throughout the night through a dedicated website (https://www.support1448.org/), highlighting the influence of queer aesthetics in mobilizing recent Thai political movements and disrupting the heteronormative discourse perpetuated by the Court.

Transitioning from this queer sensational support, a close reading of the Court’s ruling uncovers problematic reasoning deeply entrenched in heteronormative nationalist values. One particularly flawed rationale, which resonated profoundly with my experiences as a queer individual, is the Court’s assertion that marriages between non-normative individuals may not foster “deep relationships”:

The purpose of marriage is to allow a man and woman to live together as husband and wife, establishing a family unit to have children, maintain the human race according to nature’s course, and pass on property, inheritance, and family bonds between father, mother, sisters, brothers, aunts, and uncles. However, marriage between people with gender diversity cannot form such deep relationships.(12)

This ruling was a poignant reminder of the persistently heteronormative and queerphobic assumptions within Thai constitutionalism, exposing the grim reality that even though the country is generally perceived as an open-minded place for queer people, its tolerance does not mean true acceptance. The 2019 UNDRP report titled Tolerance But Not Inclusion, which surveyed attitudes towards queer people in Thailand in 2018, reveals that although non-queer people have positive outlooks about queer individuals, some of them are more opposed when it comes to queer-inclusive policies.(13) This ruling is also significant in showing how the intimate becomes the political. This deviates from the traditional role of the Constitutional Court to suppress dissenting political actors or institutions that challenge the established order. In this particular case, the ruling directly impacts the intimate life of individuals within private law. It sheds light on how public law, particularly constitutional law, influences and blurs the boundaries between the public and private legal spheres. It highlights the profound impact that public discourse can have on the intimate lives of queer individuals.

The non-binary, dynamic, and relational quality of drag aesthetics aligns exceptionally well with the concept of gender as a social construct because it challenges the static binary ontology and epistemology of law and its embedded heteronormative values. This resonates with Judith Butler’s destabilization of the dominant dualisms in the conclusion of Gender Trouble, “Genders can neither be true nor false, real nor apparent, original nor derived. However, as credible bearers of these attributes, genders can also be rendered thoroughly and radically incredible”.(14) While this social constructivist notion of gender performativity is usually cited to show the subversive power of drag performances, I want to explore further how these sentimentalist acts have the potential to generate a queer intimate public sphere that not only disrupts the heteronormative discourse but also heals the suffering that queer people face. Two studies involving interviews with Thai drag artists reveal that drag performances enhance their understanding of performative concepts of gender and sexuality despite their various perspectives on the definition of drag.(15)

Returning to the ruling on same-sex marriage, the Court’s rationale on “deep relationships” reveals its paradoxical stance, where it selectively intertwines the concept of family unit with a notion of biological naturalness, thereby disregarding the universality of natural law. Simultaneously, it invokes the nationalist notion of cultural particularism. This ambivalent attitude is manifested in this text before the mention of the “deep relationship”:

The law will be enforced sustainably if it is acceptable and does not conflict with the sentiments of the people in that country because customs and traditions shape the foundation of different legal systems. Hence, the customary and traditional laws of each country can be different. Regarding marriage, the tradition, the Thai way of life, along with prevailing practices and interpretations in Thailand, has long upheld the belief that marriage can only occur between a man and a woman. Section 1448 of the Civil and Commercial Code aligns with nature and long-held tradition.

A philosophical inquiry into this ruling uncovers the inherent contradictions embedded in the ruling’s reliance on natural-law doctrines. One stark contradiction stems from the simultaneous invocation of Cicero’s concept of “true law” and the understanding of binary biological sexes, both of which uphold the notion of natural law as immutable and universal. Paradoxically, the Court’s ruling rests on the evolving and context-specific concept of Thai traditions. This incongruity highlights the inherent tensions between the static principles of natural law and the dynamic nature of social norms.(16) The Court’s contradictory outlook shows how this political actor, under the wave of politicization of the judiciary, attempted to perpetuate heteronormative values with Thainess while invoking oversimplified concepts of early biology. Whether intentionally or not, by emphasizing Neo-Darwinian sexes as forming the human race in the natural order, the Court perpetuates the notion of binary biological essentialism. It argues that sex at birth, despite advancements in biology, cannot be chosen. According to this perspective, the law should differentiate between males and females to uphold the principle of equality. This biological essentialist notion of gender binary limits the possibilities of queer people to become an identity they desire, and I will show later how the sentimentalist relationality of drag aesthetics challenges this discourse by blurring the boundary and fostering a collective intimate sphere.

The Court also maintains that queer individuals are not prohibited from hosting a wedding or entering into private agreements regarding property. All these rationales distinctly exhibit the Court’s homophobic perspective towards queer people, and the underlying premise is that legal issues concerning queer relationships are regarded as individual issues that will not be protected under civil law. This attitude is evident in the last rationale, which suggests that queer people can establish agreements regarding property on their terms. However, these general principles in contract law do not address any legal marriage issues like those in family law, thereby demonstrating how the Court views queer issues as individual matters, denying the role of the state to guarantee the rights that they deserve as fellow human beings.

Reading this ruling from queer legal perspectives, we can discern that the underlying episteme in law is often framed as pure rationality within the conventional epistemology of legal positivism, thereby rendering it objective and relegating other disciplines to the outside.(17) This perpetuates epistemic violence that reinforces the binary oppositions between normalcy and queerness, reason and emotion, as well as public and private domains. In the legal sphere, the latter characteristics of each binary are usually marginalized and silenced in the public discourse.

Rather than allowing the Court to dictate the terms of public discourse solely, queer individuals utilize their suppressed private aspects and express themselves through queer aesthetics, such as drag, to amplify their voices within the public sphere. This approach can be seen as a transformative and unconventional way of engaging with constitutionalism, disrupting the traditional power dynamics that define the prevailing public discourse on law and policy and, at the same time, providing queer public space that is generative and heals.

Drag performances have gained increasing prominence in Thailand, a trend likely catalyzed by the launch of RuPaul’s Drag Race television shows in the country in 2018. Some scholars argue that the lineage of modern drag can be traced back to the cabaret scenes of the 1980s, which featured transgender performers lip-syncing and dancing.(18) While some individuals differentiate between drag queens and showgirls, I believe that it is crucial to acknowledge this longstanding culture as a foundational element that has helped to sustain and evolve Thai drag culture. This reflects the diverse ways in which queer individuals express themselves through the evolving art of drag in Thailand. Queer sentimentality in Thailand is plural; for example, within gay men, there are various shades of male femininity and masculinity.(19)

The first example of drag culture I will explore is a single episode from the 2023 Thai drama series Investigation of Love. The series revolves around Pat, a single mother and female lawyer who takes on a range of cases, from environmental issues to succession disputes. In one episode, Pat represents Cherry, a drag artist engaged in a legal battle over the division of their deceased boyfriend’s assets.

In a poignant hospital scene, Cherry confronts the grim reality of not having the legal authority to make life-prolonging decisions for their critically ill boyfriend. This lack of agency stems from their non-legal relationship with their boyfriend, which underscores the legal and societal barriers that prevent queer individuals from formalizing partnerships or marriages, and the consequences thereof.

In the courtroom, another drag artist named Alice, who is closely acquainted with Cherry and their boyfriend, testifies as a witness to the will. Alice confides in Pat that the will was kept secret to avoid skepticism about Cherry’s status as a beneficiary. However, the narrative takes a turn when the prosecuting attorney exposes the fact that Alice is an alcoholic and was previously declared by the Court to be a quasi-incompetent individual, which makes the will not legally valid. A flashback scene then reveals that Alice had disclosed this information to the deceased’s sister during a club visit, which the audience later realizes was an act of betrayal.

After the trial, the deceased’s family confronts Cherry and their team. The deceased boyfriend’s mother accuses Cherry of being the reason for her son’s death, but Cherry steadfastly asserts that love is love. This episode, put within the main theme of the series on legal injustice, demonstrates queer struggles with laws that do not allow queer couples to form their chosen family, and to enjoy family rights under the CCC. The character of the drag artist in this story helps emphasize the sentiments of queer people as a result of injustice in the legal system. Drag artists in this episode also show their humanity as the protagonist, who has romantic love for her boyfriend and love for her friend, who is like any ordinary individual who can have alcoholism. The subtle rendition of exaggerated arts like drag disrupts the homonationalist discourse that accepts queer people on the condition that they have to become “good citizens” according to the sociolegal script to which queer citizens are expected to subscribe. These two drag characters show that only the right to love and form a family is intrinsically sufficient for queer people to demand their rights and to be recognized by the law as constitutional citizens. Drag aesthetics in this show are, therefore, used to articulate the humanity in queer sentimentality.

Another intimate public life of drag artists is shown in an episode of the Thai documentary show, "DRAG" (2019). The episode recounts the lives of three drag artists: Angele Anang, Amadiva, and M Stranger Fox, all of whom are contestants from two seasons of Drag Race Thailand.(20) An uncensored version of this documentary with English subtitles can be viewed on YouTube.(21) As an owner of the LGBTQIA+ friendly club, Stranger Bar, M Stranger Fox shares her ambition of creating a space for the LGBTQIA+ communities and demonstrates a firm determination to pursue drag as a profession. My sense of belonging at The Stanger Bar in 2022 is one testimony that this purpose was well achieved. The Stanger Bar has continued to provide intimate public space for queer people. On 31 May 2024, the bar featured drag performances in celebration of pride month.

With a background in musicals, Amadiva articulates her dreams through her powerful and playful singing, which drives the tempo of the documentary narrative. Angele Anang, a transgender drag performer, recounts her upbringing, detailing her journey from an impoverished family to pursuing drag in Bangkok. She also expresses her frustration with the societal attitudes in Thailand towards transgender individuals, feeling perceived as less human.

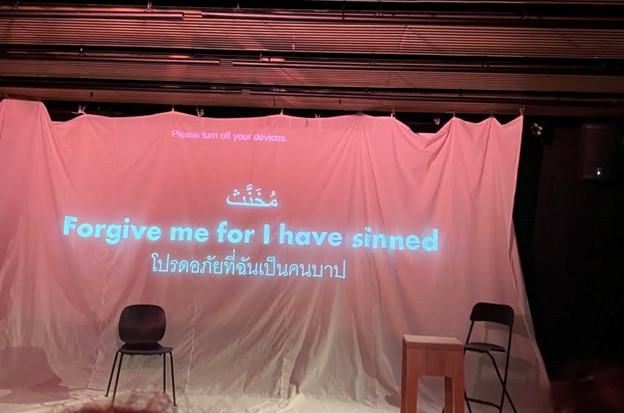

The final showcase of drag culture in Thailand, “Forgive me for I have sinned,” held in June 2024, aimed to expand the understanding of drag aesthetics within broader artistic performances. It highlighted the collaborative endeavours between drag artists and political activists. This performance was directed by Raptor, a drag artist actively engaged in political movements. Raptor, whose real name is Siraphop Attohi, often wears drag attire when participating in protests. Raptor led the “sissy” student-led protest at the Democracy Monument, which was among the many events that took place during the height of the youth protests in Thailand in 2020-2021.(22) The autobiographer, Auss, a Muslim transgender woman, told her story in a confessional manner, creating a reciprocal relationship with the audience and an intimate public for sharing experiences with the use of queer emotions. The show’s intermedial use of clips and social media posts perpetuating homophobic and transphobic public discourse, as well as Auss’s use of theatrical space and time to situate her own identities within the context of dominant history, were particularly impressive.

After the show, I had the chance to speak with Raptor and inquire about how drag aesthetics were portrayed in the performance. She mentioned that the show was inspired by her interview with Auss and incorporated drag elements as parody to create subtle social commentary. This, to me, made the message of performativity and acts of love that connect our bodies with power or any figure we believe in even more deeply inspiring. In the end, “Forgive me for I have sinned” underscored that autobiographical acts are not only a monologue to the audience but also involve many intersubjective, collaborative processes, connecting fragments of our experiences with a shared understanding of becoming a willful subject in this precarious world. In a report by Amnesty International featuring interviews with Thai LGBTQIA+ political activists in 2023, Raptor was highlighted for facing online threats simply for wearing drag aesthetics.(23) This violence against drag artists shows that structural and legal reforms are necessary to actualize both symbolic and constitutional rights for the LGBTQIA+ communities.

Figure 3 depicts the stage of “Forgive me for I have sinned”, presenting an intimate public display of various objects that Auss utilizes to narrate her life as a Muslim transgender woman in Thailand. Copyright © 2024 by Paweenwat Thongprasop. All rights reserved.

These drag narratives add details beyond the abstraction of the law to the narrative of Thai drag aesthetics and demonstrate how drag can be used as a tool to express queer inner voices, empower others, earn a livelihood, and create a queer space united by shared hope, joy, love, dreams, agony, and other nondominant feelings. This can be viewed as a form of Berlant’s intimate publics, as it becomes evident how queer intimate publics, expressed through drag, are created through the circulation of queer affects that link queer experiences with collective history. As Berlant puts it,

A certain circularity structures an intimate public, therefore its consumer participants are perceived to be marked by a commonly lived history ... expressing the sensational, embodied experience of living as a certain kind of being in the world ... it promises also to provide a better experience of social belonging ... [A]n intimate public is a space of mediation ... In an intimate public sphere emotional contact, of a sort, is made.(24)

The circulatory infrastructure of drag aesthetics has the potential to forge a community where shared embodied experiences of queerness, perceived not through intellectual but through emotional connections, bind different individuals together. Drag aesthetics can be helpful in crafting a plural interpretation of constitutionalism that encompasses and amplifies multiple experiences of queer individuals. Drag culture in Thailand demonstrate that queer individuals are fully capable of forming intimate relationships and establishing their own families. By portraying drag artists, imbued with the sensational elements of love, joy, and hope as symbols of intimate complexity within the queer communities, these narratives challenge the prevailing heteronormative legal framework which restricts queer individuals from constructing their identities and forming relationships in their ways, with their human dignity and self-determination acknowledged by both the state and society at large.

Just as the meanings in drag are processual, dynamic, and inclusive, so too must the law evolve, allowing queer individuals to fully exercise their inalienable rights—whether in forming their chosen families or simply living with the same dignity typically granted to other fellow beings. In 2020, Ruth Houghton and Aoife O’Donoghue read science fiction by women writers to offer how we could imagine a utopian image of global feminist constitutionalism that not only disrupts heteronormative norms but also creates a place for critical feminist voices.(25) Suppose we see drag aesthetics as an affective infrastructure for queer feelings. In that case, more inclusive queer constitutionalism in Thailand can be imagined through drag intimate publics that complement the abstraction of the law. Moreover, the intimate public emotions created by Thai drag aesthetics not only cut through rigid social hierarchies in Thailand but also connect Thai queer communities with other global queer communities, creating a more vibrant and inclusive global constitutionalism. This reading of drag sentimentality, I think, aligns well with Houghton and O’Donoghue’s concept of global feminist constitutionalism which focuses on the universality of feminist constitutional law.

In terms of legal culture and philosophy, there is often a reduction of queer identities to biological components or abstract language, neglecting embodied experiences and emotions. It is crucial to develop a legal, metaphysical footing that truly recognizes and embraces the diverse experiences and needs of LGBTQIA+ communities. There are also internal resistances within these communities that demand our attention.

Additionally, drag intimate publics can inadvertently contribute to the commodification of queer sentimentality. On 1 June 2024, I attended a Pride parade celebrating the passage of marriage equality legislation in Thailand. While the parade featured many drag artists, online discussions among queer individuals expressed concerns about the parade being “rainbow-washing”, dominated by large corporations in prominent positions. This queer celebration highlights the complex tension between genuine inclusive celebration and the commercialization of queer cultures, where drag aesthetics can be co-opted for purely capitalist purposes.

It is crucial to acknowledge that the inherently exclusionary nature of law, rooted in logical positivism, can silence certain voices and sentiments. Suppose law serves as a state tool that fosters Benedict Anderson’s imagined communities, wherein people of a nation unite within this socially constructed public space created by the state.(26) Therefore, I consider drag aesthetics as a form of political activism that complements and intervenes in the lawmaking process, ensuring it is inclusive and responsive to the diverse needs and experiences of queer communities.

As Thailand awaits the enactment of the marriage equality bill, it is important to note that there are queer resistances within the queer community because terms like 'mother' and 'father' are still binary and should be replaced with ‘parent’.(27) Furthermore, Thai LGBTQIA+ individuals persist in their fight for legal acknowledgment of their fundamental rights, which ought to be enshrined in specific constitutional laws. Beyond advocating for same-sex marriage, LGBTQIA+ activists are also championing other crucial legislation, such as those related to gender recognition and sex work, to establish a more robust legal framework supporting queer rights in Thailand. These ongoing efforts underscore that marriage equality law is merely an initial step toward achieving broader legislative changes for queer individuals and represents ongoing challenges in queer constitutionalism in Thailand.

Another concern I want to point out before ending this essay is the persistent false dichotomy in public discourse separating the private and public spheres. Drag aesthetics, with its potential to foster intimate publics, may help disrupt this binary. This issue was highlighted following the May 2023 election, with the new government's initiative for marriage equality. Critics contend that this initiative only superficially addresses the entrenched issues within Thai constitutionalism, rooted in royal nationalism and state violence. Additionally, some progressives argue that the legalization of marriage equality merely reinforces institutionalized marriage norms. Whether intentional or not, these critiques contribute to a public-private dualism that overlooks the increasing judicial intervention in citizens' private lives through acts of judicialization by constitutional courts and other judicial entities. Moreover, the most private aspects of life, such as family, are profoundly political—especially since the heterosexual nuclear family is a foundational structure of the nation-state. For me, the passage of the marriage equality law is historic because it signifies the legal recognition of Thai LGBTQIA+ individuals, affirming our inclusion in the state's definition of citizenship.

As a cisgender queer man with a background in law and the humanities, I am aware of my limited capacity to capture the emerging vibrant diversity of Thai drag aesthetics, which encompass a wide continuum of identities, including drag kings who challenge gender norms while redefining masculinity as well as some unique experiences with my cisgender identities. Therefore, in this essay, I focused on my personal experiences as a queer individual and law and humanities scholar who faces heteronormativity in legal studies. I have explored how Cvetkovich and Berlant’s “format” of expressions can serve as a queer infrastructure that generates alternative counter-scripts for queer people who are necessarily suffering from the dominant social script. I hope that this intersubjective writing can itself serve as an intimate public that connects my shared experiences with other queer communities. I have also added further critical voice to global feminist legal scholarship, beyond the important critiques relating to the limitations of abstract legal language, in a way that hopefully makes room for expressing some collective memory with Thai queer communities.

While people with diverse gender identities around the world have long been facing legal injustice, advocating for queer rights through the universal sentimentality of drag might offer a shared hope and struggle that queer individuals can endure. Berlant’s subtitle, “Unfinished Business”, captures very well the ongoing struggle of individuals under gender norms. By viewing the spirit of drag as something intimate, transformative, transnational, and dynamic, the fight for queer dignity in public discourse becomes an endless task that requires solidarity and support from a larger public. Let us reimagine our affective communities of global constitutionalism through drag in a way that is more inclusive, sensational, and fabulously reflective of diverse queer experiences.

* LLB (Hons), Thammasat University, Thailand. Email: paweenwat.th@gmail.com. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0000-0832-9730. I am grateful to my queer friends and drag artists who inspire me to write about the intimate publics of queer communities in Thailand. I also thank everyone who provided feedback on earlier versions of this essay. Special thanks to Dr Julie McCandless for her editorial suggestions and to the participants of the Law’s a Drag roundtable by Juris North and the Law’s a Drag network for their reflections on drag and queer legal research.

(1) Lauren Berlant, The Female Complaint: The Unfinished Business of Sentimentality in American Culture (Duke University Press, 2008) viii.

(2) Ibid, vii.

(3) Samia Hesni, ‘How to Disrupt a Social Script’ (2024) 10 Journal of the American Philosophical Association 24-45.

(4) See further, Carolyn Pedwell and Gregory Seigworth (eds) The Affect Theory Reader 2: Worldings, Tensions, Futures (Duke University Press, 2023).

(5) Ann Cvetkovich, ‘Format as Infrastructure: Ann Cvetkovich on Lauren Berlant’ (2021) 2 Capacious: Journal for Emerging Affect Inquiry i.

(6) Berlant (n 1) viii.

(7) Danish Sheikh, ‘Staging Repair’ (2021) 25 Law Text Culture 144-177.

(8) Amnesty International, ‘Thailand: Passing of Marriage Equality Bill a Triumphant Moment for LGBTI Rights’ (18 June 2024). Available at <https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2024/06/thailand-passing-of-marriage-equality-bill-a-triumphant-moment-for-lgbti-rights/> (last accessed 7 August 2024); Fortifyrights, ‘Thailand: Thailand Legalizes the Right to Marriage for LGBTI+ Couples’ (18 June 2024). Available at <https://www.fortifyrights.org/tha-inv-2024-06-18/> (last accessed 7 August 2024).

(9) Chalermrat Chandranee (tr), ‘Constitutional Court Ruling No 20/2564’ (2021) 5/2021 Justice in Translation. Available at <https://seasia.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/1794/2021/12/Constitutional-Court-1448-FINAL.pdf> (last accessed 7 August 2024).

(10) Anna Lawattanatrakul, ‘Next Steps on Thailand’s Road to Marriage Equality’ Prachatai English (3 December 2021). Available at <https://prachataienglish.com/node/9596> (last accessed 7 August 2024).

(11) Tyrell Haberkorn, ‘Under and Beyond the Law: Monarchy, Violence, and History in Thailand’ (2021) 49 Politics & Society 311-336.

(12) This is my translation of Constitutional Court Ruling No 20/2564, 8, which seeks to retain the literal words used by the court in the Thai language to show heteronormative assumptions in the legal language.

(13) United Nations Development Programme, Tolerance But Not Inclusion (2019). Available at <https://www.undp.org/thailand/publications/tolerance-not-inclusion> (last accessed 7 August 2024).

(14) Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (Routledge, 1990) 180.

(15) Sakol Sopitarchasak, ‘What It Means to Be a Drag Queen in Thailand: A Qualitative Study’ (2023) 23 Asia-Pacific Social Science Review 1-17; Sijhana Virakul, ‘Phet: Thai Drag Artists’ Perspectives of Thai Sex, Gender, and Sexuality’ (2023) 11 Journal of Student Research 1-16.

(16) Pudit Ovattananakhun, ‘Application of Natural Law Doctrine in Constitutional Court Decision No. 20/2564: A Jurisprudential Analysis’ (2022) 2 Thai Legal Studies 227-250.

(17) Damir Banović, ‘Queer Legal Theory’ in Dragica Vujadinović, Antonio Álvarez del Cuvillo and Susanne Strand (eds), Feminist Approaches to Law: Theoretical and Historical Insights (Springer International Publishing, 2023) 79-91.

(18) Chertalay Suwanpanich, ‘Thailand’s Drag Shows: Testimony to Survival and Culture Redefined’ Thailand Foundation (22 June 2022). Available at <https://www.thailandfoundation.or.th/culture_heritage/thailands-drag-shows-testimony-to-survival-and-culture-redefined/> (last accessed 7 August 2024).

(19) Narupon Duangwises and Peter A Jackson, ‘Effeminacy and Masculinity in Thai Gay Culture: Language, Contextuality and the Enactment of Gender Plurality’ (2021) 14 Asia Social Issues 248926-248949.

(20)Thai PBS, ‘Klang Mueang: DRAG’ (29 October 2019). Available at https://www.thaipbs.or.th/program/KlangMuang/episodes/64309 (last accessed 7 August 2024).

(21) ANU, ‘DRAG - Documentary ThaiPBS Uncensored Version - Angele Anang, Amadiva, M Stranger Fox (ENG SUB)’ (YouTube). Available at <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ahCT-OfEEys> (last accessed 7 August 2024).

(22) Paisarn Likhitpreechakul, ‘Sissy That Mob: LGBT Youths Front and Centre in Thailand’s Democracy Movement’ Prachatai English (15 September 2020). Available at https://prachataienglish.com/node/8788 (last accessed 7 August 2024).

(23) Amnesty International, Being Ourselves is Too Dangerous: Digital Violence and the Silencing of Women and LGBTI Activists in Thailand (2024). Available at https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/asa39/7955/2024/en/ (last accessed 7 August 2024).

(24) Berlant (n 1) viii.

(25) Ruth Houghton and Aoife O’Donoghue, ‘“Ourworld”: A Feminist Approach to Global Constitutionalism’ (2020) 9 Global Constitutionalism 38-75.

(26) Sundhya Pahuja and Ruth Buchanan, ‘Law, Nation and (Imagined) International Communities’ (2004) 8 Law Text Culture 137-166.

(27) ILGA Asia, ‘Thailand: Thailand legalises same-sex marriage with the passing of the Marriage Equality Bill’ (26 June 2024). Available at <https://www.ilgaasia.org/news/ThailandPressRelease2024> (last accessed 7 August 2024).