Paola Zichi*

…It looked as if for once it was going to pay to be merely a woman, after a life-time hitherto spent regretting it. If one was to be respected by the rebels and ignored by the Government, and able to hike about the country without let or hindrance from either side, it would certainly be worth it.

‘School Year in Palestine 1938-1939’ by Hilda Wilson(1)

Hilda Mary Wilson served as school teacher at the Arab High School in the village of Birzeit in 1938-1939 during the first Arab Revolt (1936-1939), witnessing a controversial period of the British Mandate for Palestine. Wilson’s account of the Arab rebellion is set in Palestine in the decade following the Western Riots of 1929. This decade proved to be a turning point in the history of the Palestinian Mandate, as it was marked by the first national resistance uprising and followed by the first recognition of the Arab grievances concerning Palestine by the Shaw Commission Report.(2) The Great Arab Revolt unfolded in the years 1936-1939 and was followed by legal repression measures introduced by the British authorities in order to deal with it. Hilda Wilson’s writing represents a detailed account of the emergency regulations adopted by the British authorities to quell the insurgency. As an unconventional source of legal history, Wilson’s autobiographical memoir illustrates how she negotiated her white privilege and Western identity in relation to the Arab and Jewish self-determination claims for the land of Palestine. Her ideas of (British) justice, gender identity and citizenship were reflected in and imbued her life and personal writing, offering an account of the entrenched realities of domination and agency in Palestine regarding gender and law in the Mandate Period.

This article attempts to introduce a more detailed enquiry into the real-life experience of women, in order to give a more contextual, complex and relational account of the life of law in the Mandatory ‘peripheries’ during an anti-colonial uprising. It aims to investigate how Wilson negotiated her white identity and privilege with the local community and the government within the colonial frame. Wilson’s relationship with the indigenous anti-colonial revolt and her experience of the repression that followed it, as Palestine was subjected to “statutory” martial law,(3) is investigated through a post-colonial legal approach which attempts to re-write legal histories from below.(4) An explicit feminist perspective focusing on the intersections between gender, race and law is employed in order to give a different account of the space for women’s agency and self-determination in Mandatory Palestine. Hilda’s memoir is used here to highlight how the personal freedom and autonomy of women could be enacted within overlapping systems of justice and in the normative space unexpectedly left unconstrained by the rule of either the British Government or the native rebels. Written by a woman who was “ignored by the British government and respected by the rebels”,(5) Wilson’s diary constitutes an illuminating historical source on the use of privileged white identity in an anti-colonial setting. As part of a broader critical legal approach to the history of law,(6) this article aims to intervene in the discussion on methods and methodology in the writing of legal histories. In terms of methods, the paper relies on primary materials such as diaries as the primary tool for legal research. In terms of methodology, it attempts to apply a new interdisciplinary methodology to the understanding of legal order/disorder and to the construction of hybrid legal subjectivities.

More precisely, this article combines three different methodological perspectives on feminist legal history. First, Wilson’s experience of colonial law is investigated “from below”, i.e endorsing a socio-legal perspective which looks not to those who made the law, but rather to those who were bound by it: this is a history that takes as its subjects the ordinary people and reflects on their real-life experience in order to disrupt stereotypical legal narratives of oppression and resistance.(7) This approach is inspired by a type of scholarly literature which seeks to disrupt the universal and homogenising narratives of law to focus on how juridical and political processes are intertwined in creating areas of resistance: looking at how law is experienced, then, becomes fundamental in order to understand the places of contestation that it seeks to regulate.(8) Secondly, the article adopts a post-colonial legal approach to reflect on the hybrid construction of legal subjectivity. In this sense, the story told by Wilson is both epistemologically and methodologically fruitful for an investigation of how race and gender constitute aspects of legal positioning and privilege in a (post)colonial context. This investigation aims at challenging and transforming pre-constituted and dichotomic legal narratives of the colonial encounter. These two perspectives are held together by the materiality of an artefact, Wilson’s curfew pass, to reflect on how she negotiated her positionality while supporting the indigenous revolt. Thirdly, the article investigates our understanding of legal order and disorder through the act of diary writing, while also discussing the value and the limitations of using an English woman’s memoir as a historical source for the legal history of women. Finally, thepublishing history of Wilson’s diary is also considered, in order to reflect on archival politics and on the processes and choices that decide whether or not marginal voices are recovered and remembered.

Wilson wrote her memoir, entitled School Year in Palestine 1938-1939, at the time when so-called emergency regulations were enacted to deal with the first Arab revolt, which spread in opposition to the British authorities and the increasing Jewish immigration in the land of Palestine. In her writing, she tells the story of an English woman living in Birzeit, with a part-time teaching job, who hitch-hiked from Birzeit to Jerusalem on week-ends. Wilson narrates both the life of the community during the state of emergency and her multifaceted relationships with local villagers, the (female) Arab management at the school, rebels and British troops. Her scholarly appeal lies here, at the crossroads of her gender and national identity.

Since this article aims to be a methodological enquiry on a particular form of agency and resistance to colonial sovereignty by its subjects, a preliminary definition of “state of emergency” is required. The expression refers to the use of executive power to suspend the rule of law, and the transference of power to the police or the military.(9) More broadly, it indicates the difference between lawful violence – the violence that is regarded as the exclusive right of governments and states – and lawless violence – the violence that is deemed illegitimate by governments and states. The latter is branded as outlaw terrorism and insurgency, thus implying that the state “has a monopoly on the legitimate use of violence” and the power to define what terrorism means.(10) The definition of terrorism in Mandatory Palestine becomes more complicated during the colonial period, as another insurgent force adopted “terrorist methods” to fight “British terrorism”, i.e. the Zionist movement.(11) The Zionist movement considered the British Authorities as the colonial power that had to be removed from Palestine in order to “liberate their land”.(12) The teaching experience of Hilda Wilson is situated in this context, and her account of daily life under the colonial state of emergency – in other words between British curfew orders and raids on the one hand and the regular incursions and demands of the Palestinian rebels on the other – offers fruitful insights on the agency and privilege enjoyed by women as well as on epistemology and law under a colonial state of emergency.(13)

In fact, although there is agreement on how the definition of terrorism fails to address the role of the authority and power of the state in defining what terror is, and the need to treat the “state of emergency” as a juridical and political category used by states to justify their violence and repression,(14) what remains largely ignored is an account of the histories of women in a colonial setting that can challenge traditional narratives of constituted power and constituency resistance, and this dichotomy itself, with the aim of providing a more gendered legal history.(15) Studying the lives of British women in the empire might thus illuminate other intersectional spaces of international law, subverting fixed and pre-constituted assumptions with regard to the political juxtaposition of order/disorder in the colonies. Mbembe argues that:

colonies are similar to the frontiers. They are inhabited by “savages”. The colonies are not organised in a state form and have not created a human world […] They do not establish a distinction between combatants and non-combatants, or again between an “enemy” and a “criminal”. In sum, colonies are zones in which war and disorder, internal and external figures of the political, stand side by side or alternate with each other. As such, the colonies are the location par excellence where the controls and guarantees of judicial order can be suspended – the zone where the violence of the state of exception is deemed to operate in the service of “civilization”.(16)

On 19 April 1936, the British High Commissioner of Palestine, Arthur Grenfell Wauchope, declared a state of emergency in Mandatory Palestine. The power to declare a public emergency was given to the British High Commissioner by a 1931 Palestine Defence Order-in-Council,(17) which authorised him to enact such regulations “as appear to him in his unfettered discretion to be necessary or expedient for securing public safety, the defence of Palestine, the maintenance of public order, the suppression of mutiny, rebellion, and riot and for maintaining the supplies and services essential to the life of the community”: it is within this normative context that Hilda Wilson’s diary has to be read.(18)

The article is divided into two parts: the first part focuses on the methodological aspects of shedding light on women’s legal history. It aims to highlight the chosen theoretical framework while at the same time to discuss the limitations and constraints that characterise autobiographical accounts as a definitive historical source. The second part introduces the content of Hilda Wilson’s memoir and deals with her account of the revolt, considering her life in Palestine between the hills of Birzeit and Jerusalem, and her relationship with the Government and the rebels.

Part 1. On Methodology and on Artefact: Hilda Wilson’s Curfew Pass

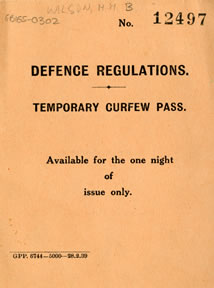

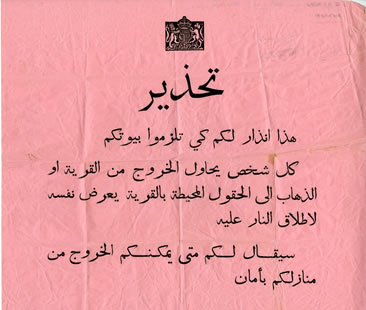

Figure 1. Curfew Notice, 1939. Arabic curfew notice that was dropped by airplane. The writing states “This is a warning to you to keep indoors. Any person who tries to leave the village, or to go to the fields surrounding the village, is liable to be shot. You will be told when you may safely leave your houses.” Wilson, H.M., GB165-0302, Middle East Centre Archive.

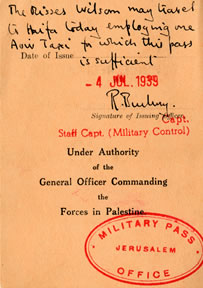

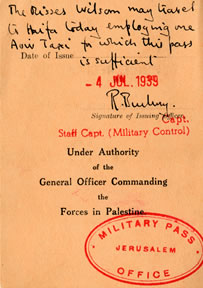

Figure 2. The Defence Regulations Temporary Military Curfew Pass which Miss Wilson and her sister used to travel away safely from Palestine in July 1939. Wilson, H.M., GB165-0302, Middle East Centre Archive.(19)

At the Middle East Centre archive, as I was looking at Wilson’s temporary curfew pass, the permit that legitimised crossing the lines between the two conflicting claims for self-determination over Palestine, I was urged to reflect on the shape that law takes when enacted on the ground. The material (i.e. normative) ground was, in the case of Hilda Wilson, regulated by a particular international legal framework: British presence in the Near East was legitimated by the Mandate System, a “hybrid” colonial,(20) constitutional and administrative device that the League of Nations Covenant envisaged to grant international supervision and assistance to those people who were “not yet able to govern themselves under the strenouous condition of the modern world” (par.1 art. 22). Since its inception, the League of Nations reflected the view that the new global order was to be found in the concept of civilisation, and this order was defined by the dominant powers.(21) The Mandate system was the administrative and bureaucratic device through which uncivilised people would become civilised; only afterwards could they acquire rights and shoulder obligations, such as the right to self-determination and independence.(22) However, in the case of anti-colonial insurgency, the philanthropic linearity of this international law teleology broke down: the fear of chaos, arbitrary justice and the spectre of anarchy were used to justify the brutal repression of the indigenous uprising. Accounts of local insurgencies both challenge and reproduce the idea of “history as a grand, progressive narrative through which Eurocentric narratives are totalised as the accurate account of all humanity. It is a position that views human history as moving forward, towards a single and common goal, frequently defined in terms of liberal democracy, good governance and the rule of law”.(23) Local insurgencies are irrational, violent, contagious, dangerous and “law is situated in this vision as an objective, external, neutral truth that propels us into the future, providing stability to the societies in which it operates and steering us carefully along the path of maturity, development and civilisation”.(24)

In this section, I attempt to outline a counter-interpretation of this stereotypical legal narrative, drawing on different theoretical approaches: on the one hand, there is a socio-legal perspective that challenges one-dimensional and textual accounts of legal histories which dismiss, marginalise and ignore the experience of the subordinated within a self-reproducing and self-perpetuating dominant narrative; on the other, the article draws on postcolonial feminist legal theory, asking what alternative readings of the legal order can emerge when looking at law at the level of the everyday experience of the racialised and gendered individuals that experience it.(25) In this sense, the curfew pass of Hilda Wilson, an English literature teacher serving in Palestine during the so-called first Arab Revolt (1936-1939), is used to epitomise these two approaches and to question the dichotomic combination of law/order and insurgency/disorder as synonymous with the justice system of the modern imperial state and that of the local indigenous insurrection. It is also used to further a different critique of the liberal doctrine, challenging the assumptions upon which the ‘Other’, i.e. the “Palestinian rebels”, have come to be produced, and posing the question of agency and resistive subjects created in response to the pressures of colonial repression.

The textual and internal understanding of how international and military laws operated in Mandatory Palestine gives a short-sighted account of the experience of law in the colony, of the relation between law, identity and privilege, as well as between law and gender. Indeed, much of the scholarship on the history of law and gender has focused on the methodological shift from the inclusion of the marginalised subject of the discipline to “gendering” the discipline of law in itself, challenging the same assumptions about what counts as legal history and who are its actors, as well as recognising how race, gender and sexuality have been central in structuring law and the legal subject.(26) Exploring the intersections of gender and legal history then leads to a further questioning of the familiar narratives of civilisation, progress and loss. Furthermore, the use of gender as a tool of analysis challenges our established understanding of the foundations of the legal discipline, such as narratives about the construction of the liberal state, citizenship and subjects.(27)

In this sense, rather than endorsing a dichotomous perspective which sees law as a mechanical instrument to assist domination or resistance, law could also be considered as the battlefield for rethinking self-determination from its individual basis.(28) Dipesh Chakrabarty compels us to consider how the role of law in creating identities – in excluding or subjecting others – is not intrinsically a neutral project. On the contrary, it constitutes a form of manipulation which can be corrected through the gradual process of inclusion of these previously excluded groups.(29) Unfortunately, this perspective does not engage with the terms on which inclusion is determined, nor, as in the case of Hilda Wilson, with the complex political relation between the past and the present, and of both with the future. In this sense, a feminist intervention on a post-colonial approach to the writing of legal histories aims to expose

how the liberal project lacks an emancipatory potential, and forces us to revisit feminist legal histories and the politics of meaning from a postcolonial perspective. At the same time the postcolonial project must not be regarded as merely a response or reaction to liberalism, but rather as produced in and through the colonial encounter. The relationships of domination and subordination continue discursively to infuse the present, albeit in different ways, and to provide an analysis and critique that can account for the complex relationships between law, sexuality and culture that are not explained through older, tattered frameworks.(30)

Wilson’s Curfew Pass thus represents the exceptionality and individuality of law. Since it was used against the Mandatory authorities’ repressive measures, Wilson’s pass comes to constitute both the evidence of Wilson’s white privilege and the possibility for a strategic solidarity, providing us with a more nuanced account of the juridical dimension when writing the legal histories of women. Considering the temporary curfew pass as an artefact compels us to question the expansion of international law across time and space, as well as the relations between history-writing and methods.(31) The centrality of the artefact is exemplified in history through the intense debates about “what counts as the archive, and [in anthropology] through the equally intense debates about what counts as the field: the artefact, the materiality of the object, comes then to signify the willingness to explore and redefine both the field and the archive of international law”.(32) In this sense, it enables the study of how international law operates in practice, from how it is produced on a global scale to its localisation on the micro level. In rejecting the depiction of the rebels' identity and behaviour as backward, terroristic and primitive, but rather describing them as complex and multi-faceted characters in the context of the anti-colonial revolt, Wilson’s diary and pass illustrate the ambivalence of law as a textual device and the materiality of law as political mediation.

The value of considering Wilson’s pass as an artefact resides in the willingness to break down conventional imperial/hegemonic narratives of law as instrumental to the dichotomy “colonised/coloniser”. It offers a more blurred account of the negotiations and of the multiple contextual identities that law happened to forge: an artefactual reading of international law then supplements the desire for historical “closure” with an awareness of the complexity of the relationship between past and present when working in the archive of and as international law.(33) Moreover, the use of a legal artefact may also be a way of rethinking one of the main assumptions that shapes (international) law: the legal subject. Wilson’s identity cannot be conflated with her British citizenship: by reversing her white privilege against her mother country’s “national interest” to sustain Palestinian resistance, her real-life experience challenges the idea of a fixed subject. The idea of a legal subject is therefore complicated by taking into account processes of subjectivisation at the intersections of race, gender and class. The use of a post-colonial methodology becomes then a way to restate the inextinguishable connection between law and politics, and the need to abandon the ideal autarchy of both juridical and political discourse.(34)

A final methodological approach to how we write feminist legal histories is to reflect on Wilson’s diary as a legal source in contrast to the traditional sources of law: “since progress is the lens through which, conventionally, this imperial past comes to be known as past, and the present as modern, a second level of analysis might question the way in which materials are chosen and organised as assemblage of sources that evidence the meaning of this progress”.(35) In this account, international treaties, diplomatic papers and doctrinal sources constitute a particular “order of things”.(36) On the contrary, Wilson’s memoir of the Arab revolt compels the reader to adopt a different perspective with regard to the behaviour of British troops in a time of revolt, providing a privileged observation site to challenge pre-constituted assumptions about colonial governance and emergency regulations. Since Wilson’s diary may be used to challenge the orientalist racialised account that justifies the colonial use of force and military intervention in the Mandatory setting, it can be argued that drawing from life-writing sources enriches our understanding of the real-life experience of low-level justice as well as our concept of individual personhood in the time considered.(37) Wilson wrote her diary because she “found that people in England had little idea of what was actually going on in Palestine”.(38) Yet this willingness to tell the truth about Palestine, to witness and to report, involves the complexities of textual self-representation and the publicity entailed therein, so that it must be treated with caution. However, one might argue that it is exactly that slippage between a self-representational subjectivity and its legal dimension that makes it worth investigating.

It has been widely debated whether the intra-disciplinary tension between legal history and socio-legal studies can be offset by offering a controversial or revisionist account of the legal experience. Thus, this account implies a fundamental reversal of the categories through which we think law: authoritative subjects, methods and sources. (39) This can be questioned by virtue of the issue of self-representation: if Wilson’s primary concern was to inform the British public of what was happening in Palestine, it can be assumed that her diary is a life-writing text that constructs Hilda Wilson as a textual literary subject, whose self-representation is inextricably tied up with her juridical dimension. Through her diary, Wilson shows understanding of the processes of law, of juridical procedures, and of the meaning of (international) justice. However, Wilson’s account of the brutalities of the British troops in Palestine during the revolt could be questioned, as she might misrepresent them in order to maintain her own textual self-construction, that is, her hybridity and her “consciousness of belonging to the two sides”.(40) The sides are here interpreted as the “British sense of justice and fair play” and “the Palestinians’ claims to self-determination”.(41)

It has also been argued that women’s memoirs should be treated with care given their “scientific” value: since they constitute individual experiences of the justice system, they are singular case studies that have allegedly limited value for redefining theoretical propositions. However, since the methodological premise of this article is to repudiate totalising legal narratives and to show the entrenchments and negotiations of gender and law in Mandatory Palestine, Wilson’s diary constitutes a precious source for shedding light on women’s legal histories. In its context, Wilson’s curfew pass serves as an allegory of the transformative power of law, doing and undoing the legal and political meaning of the artefact according to the circumstances and contextual needs of the time. Because Wilson was a white female citizen of the British Empire, she was allowed to enjoy her freedom of movement in the territory of the British Mandate in a moment when the native population was under de facto martial law. At the same time, her privilege served the needs of the community around her: it was used to bring mail, medicines and materials to the school for the inhabitants of Birzeit – i.e. for the civic functioning of the village-community.

The recognition of the value of life-writing sources for the construction of feminist legal histories has been discussed by Auchmuty.(42) In her writing, she explains how historians researching on women’s legal history have to be “imaginative” in the search “not only for source material but actually for women’s subjects to research, and to ask different questions of the public records that do survive and have been written up in the past”.(43) Through Wilson’s manuscript, the reader has the opportunity to travel to the unknown, witnessing a process of knowledge production as a site of both learning and unlearning, tension and contestation. This is of fundamental importance when it comes to understanding how assumptions about political resistance and cultural differences of “the other” came to be produced and continue to operate in the present.(44) Wilson’s memoir offers the opportunity to explore the everyday life of the colony, even when Wilson’s positionality makes her account of the everyday life of the resistance movement not fully trustworthy for investigating the juridical and cultural habits of the people of Palestine. Nevertheless, Wilson’s memoir might constitute a point of departure not for investigating the Palestinians, but rather the prejudices, beliefs and codes of behaviour of a white British woman at the crossroads between different juridical systems.

A concluding remark on Hilda Wilson and her account of the British emergency regulations in Palestine comes from the publishing story of her diary. Wilson’s diary was acquired by the Middle East Archive in 1968. In her correspondence with the archivist, Hilda Wilson wrote:

In correspondence with friends in England I found that people in England had little idea of what was actually going on in Palestine. So, I kept this detailed diary, and on returning to England at the outbreak of World War II (autumn 1939) I typed out a narrative version and tried to get it published. No publisher would take it, because – they told me – it contained things derogatory to the British troops and such things could not be publicised in wartime. So, I waited and tried again when the war was over. I was then told that these matters were out of date and nobody would be interested anymore.(45)

The replies made by the archivists are of importance when considering the structural constraints of knowledge production and the responsibility of the different actors – writers, historians, publishers and archivists – in the access to and processes of history writing. Wilson could not publish her manuscript for reasons of State, at a time when her account of the British brutalities in Palestine could delegitimise the British Mandatory Government. In later decades, in the context of the Cold War, the historical value of her diary was deemed irrelevant. If it can be argued that publishers must consider the intellectual and ideological circumstances existing at the time of publication, it is equally important to recognise their responsibility in producing and influencing such circumstances. In this sense, adopting a feminist methodology in archival work might lead not just to the uncovering of forgotten records and the consequent possibility of writing different histories, but also to a more critical engagement with the social and legal structures that reinforce the power imbalances in the access to knowledge production. There are many reasons why Wilson’s diary might have been deemed irrelevant: the fact that there were fewer publishing houses and that publishing costs were higher might not have facilitated its publication; the length of the paper might also have been an obstacle: the manuscript is too long for an essay and too short for a book, and uncertainty about the format could have led to the abandonment of the source. Moreover, her gender might also have played a role in relegating her story to oblivion.

Part 2. The Story of Hilda Wilson and the First Arab Revolt

Hilda Wilson received an offer of a part-time job from the British Government’s Department of Education in summer 1938. Her posting lasted one year, during which she taught English Literature to Arab students in an Arab-run school, the Arab High School in Birzeit under the direction of Miss Nabiha Nassar, who founded the school in 1924. During this year, the British Government’s repression of the Arab Revolt was at its peak, as Hilda Wilson recalls in her diary which covers the period 1936-1939. Wilson takes a nuanced position in relation to the factions, rivalries and position of the rebels:

the situation being characterised of an actual state of martial law, where curfews, raids, collective fines, punishment and rough killings in the major cities of Palestine were the norm. It represented the supreme effort of a people struggling for their national existence, knowing well what a desperate thing it was for a tiny nation, less than a million, to challenge the armed might of Britain, but confident that by such a venture they would compel the world’s attention to their grievance, before superior military force overwhelmed them.(46)

Widely known as the “Great Revolt”, or as the first nationalist anti-colonial uprising by Palestinian Arabs in Mandatory Palestine, against the British administration of the Palestine Mandate, it demanded Arab independence and the end of the policy of open-ended Jewish immigration and land purchases with the stated goal of establishing a “Jewish National Home”. The uprising followed the declaration of Hajj Amin Al Hussein calling for a general strike in 1936, an uprising that was branded in the Jewish Yishuv as “immoral and terroristic” and often compared to fascism and Nazism. The revolt consisted of two different phases: the first phase was directed by the Arab Higher Committee and focused mainly on the strike.(47) It ended when the British civil administration used a combination of political concessions, international diplomacy and the threat of force. The second phase, which began late in 1937, was a peasant-led resistance movement which was provoked by the British repression in 1936 and increasingly targeted British forces. During this phase, the rebellion was brutally repressed by the British Army and the Palestinian Police Force, which employed repressive measures intended to intimidate the Arab population and undermine popular support for the revolt. The peasant-led resistance was organised by “Faisail” units, stronger in the hills and mountains in inner Palestine, as opposed to the highly populated, urban, economically developed, Jewish-controlled areas on the coasts. In this context, in Birzeit, a small village sixteen miles away from Jerusalem, Wilson wrote her diaries. The small quote at the beginning of this article constitutes a preliminary source of information about her political stand on the Palestinian question: being nurtured by a Palestinian environment, she unequivocally shows her support towards the Palestinian rebels and their struggle, qualified as an anti-colonial national struggle fighting for self-determination against the military and strategic superiority of the British imperial power in the East. Wilson’s diary mostly focuses on the repressive measures adopted by the British forces to crush the uprising: to question which legal emergency measures were implemented and how social relations – in the school, in the village, in the relations between the peasant-villagers and the organised rebels – reacted to and developed together with them is the main object of her report, and consequently of this analysis.

Wilson was not the only English woman residing in the Empire and reporting on the anti-imperial movement caused by the colonial presence. For instance, Frances Newton reports in her autobiography Fifty Years in Palestine(48) that the revolt in Palestine started when the killing of two Jews travelling from the Haifa coast to Tulkarem on 9 April 1936 led to Jewish reprisals. After the funeral of one victim in Tel Aviv, the nearby Arab city of Jaffa was attacked. Arabs in Jaffa then retaliated by coordinating to close their shops, soon followed by shopkeepers in other cities of Palestine. The strike officially started on 20 April, when the Nablus Arab National Committee, composed of the notables of Nablus, decided to back the strike until the British Government would satisfy their demands. The leaders of the Arab parties at that time created the then Arab Higher Committee, which again restated the Arab claims presented to the British Government, as: 1) an end to Jewish immigration, 2) legislation to prevent the further sale of Arab land to Jews, and 3) the establishment of a national government responsible for the election of a representative council. Without any response from the British Government, the general strike continued in the period considered as the Arab revolt, or the first Arab Revolution.(49) It is worth recalling the work of the Peel Commission or Palestine Royal Commission, headed by Lord Peel, which in August 1936 was empowered to go to Palestine and to undertake a full enquiry as to the cause and possible cure for the revolt; but the members of the Royal Commission did not reach Palestine until 11 November.(50) Before the Peel Commission arrived in Palestine, another Arab memorandum went to the High Commissioner and was signed by 137 senior Arab officials and judges, explaining that the disturbances were due to a feeling of despair among the Arabs which had largely been caused by the loss of faith in the value of official pledges and assurances for the future; that the Government failed to realise that the trouble could not be stopped by mere force, but only by removing the root causes of it and that the Arabs were consciously protesting against the present policies of repression. Due to the intervention of King Ibn Saud, King Ghazi of Iraq and the Emir Abdullah of Transjordan, the Arab Higher Committee – which included officials of the administration, political parties, notables and all the Palestinian judges – decided to call off the strike and allow the Royal Commission to reach Palestine and start its investigation.(51)

The political and social situation differed according to the various geographies of the place. Among the accounts of several British teachers residing in Palestine in those years, the memoirs of Hilda Wilson are particularly striking, for both technical and historical reasons. Wilson reports a particular moment of the Arab resistance in Palestine in the village of Birzeit where the rebels’ resistance was robust — compared to cities in the coastal areas — and when her privilege as a white British woman was used in solidarity with the Palestinians in protesting against the British Mandatory authorities. She describes in particular the realities of her teaching experience in the hills, while the British authorities had imposed censorship and harsh curfews on all the inhabitants.(52) In the descriptions, Wilson explains how her identity allowed her to move in the intersectional gaps between different overlapping systems of justice, or between the popular and resistant justice (the juridical code of conduct of the resistance movement and of the rebels), the justice of the coloniser (the state of emergency), and the previous mosaic of administrative, criminal, civil and procedural rules in force at the time (English, Ottoman, Sharia and indigenous systems of rules).(53) In this context, she acknowledges her privileged position, e.g. when she recalls the general situation of those years:

By August 1938 the rebels were in occupation of the whole central hill-country of Palestine with the exception of Jerusalem, and even there the infiltration into the old walled city was only put a stop to by a five-day British military campaign during October, when the old city underwent a miniature siege. Jericho, Ramallah (10 miles from Jerusalem) Bethlehem (6 miles) in turn closed their government offices, post offices, bank, police station, as each district passed under the control of the rebels and local British authority came to an end. […] Temporary curfews were frequently imposed by government in Jerusalem and Haifa and a permanent curfew on all main roads in the country after 6 P.M. Travel of any kind without a permit was forbidden in the autumn of 1938. Commerce and economic life were almost at a stand-still; hundreds were starving, and hundreds were in prison or concentration camps. In the Arab villages, heaps of rubble marked the site of houses blown up by British troops by sheltering rebels; and the peasants, who at the best of times scraped only the barest living from their corn-plots and olive-groves on the rocky terrace hillsides, were now harassed one day by rebel bands demanding food or money and the next day by British soldiers searching for arms or exacting punishment for their having received the rebels ….

The situation in Palestine at the height of the Arab rebellion (summer 1938 to summer 1939), though grim enough in most ways, was not without its humor. These did not lie on the surface, perhaps, but they became plain to anyone who had a part-time job in an Arab village at the time when normal traffic was at a standstill and was compelled to get into and out of Jerusalem, sixteen miles away, by means of casual lifts. There was humor, too, in the consciousness of belonging to both sides; teaching Arabs in a national school under Arab management, meeting armed rebels in the village (at a time when the possession of arms was punishable by death) and being offered, though declining, their escort down to the main road on Friday afternoons, and then on the main road accepting a lift into Jerusalem with British troops who would give a month’s pay for the chance of a shot at those same rebels.(54)

Humour, in the consciousness of belonging to both sides: the situation during the uprising of the first anti-colonial and national movement troubled both Hilda Wilson and other teachers who worked in Palestine, such as Susanne Emery, who worked in an English girls’ school in Haifa.(55) While Emery seemed more naively surprised when she realised how English literature was “full of ideas of freedom and nationalism”, which made its teaching to the young Arab students uncomfortable, and she opted not to inflame their minds at a time when they had already been placed in an uneasy situation of conflict, Wilson gives a more detailed account of the realities of a British woman’s inner dilemmas between law, life and literature. The chosen curriculum of the first semester of the school year 1938-1939, one of the harshest periods of the revolt, required Wilson to teach Milton’s Areopagitica, a 1644 prose polemic by the English poet arguing against licensing and censorship in defence of the principle of a right to freedom of speech and expression, and Shakespeare’s Hamlet. She recalls in her diaries the reaction of one of her students:

Considering the state of feeling throughout the country, it was remarkable how nice that top class was, studying English literature, with an English woman at a time when their country was in revolt against the British government. They had an engaging habit of coming out with some rabidly anti-British remark, then pulling themselves up in horror with ‘Oh Miss Wilson! Of course, you are British! We don’t mean you – we don’t mean you’. Khalid, a lanky yellow-head in the front row, was my prop and stay, always to be depended on for a thoughtful answer or a lively question: this for instance, arising out of an extract from Milton’s ‘Aereopagitica’ on the Freedom of Press:

“Why do the British encourage a free press in England and not allow it in Palestine?”(56)

Indeed, Khalid remarks, the repressive measures put in place by the British Government at the time of Wilson’s reporting (autumn 1938) had been strengthened to the point of being considered a sort of statutory martial law. In fact, additional Regulations had already been published on 22 May 1936, and gave District Commissioners additional powers such as the capacity to place persons under police supervision and to restrict their movement from one part of Palestine to another.(57) On 1 June, further additional Regulations were published which gave the District Commissioners the power to order the opening of shops and business premises which had been closed on account of strikes and to order the detention of persons in internment camps for a period not exceeding one year, and gave powers of arrest without warrant to members of the fighting forces. The additional Regulations of 6 June made provisions for the infliction of death sentences or life imprisonment in certain circumstances, for shooting at the troops or police, bomb-throwing or dynamiting, acts of sabotage, and acts endangering the safety of ships, aircraft, trains and transport vehicles.(58)

Under these Regulations, the Government also assumed the authority for impounding labor to clear roads obstructed by barricades, nails, etc., for controlling the publication of newspapers by issuing of permits, for levying collective fines upon inhabitants of towns or villages who had committed an offence or connived at its committing, and for demolishing houses from which firearms had been discharged or for other crimes of violence committed. The additional Regulations of 25 August made it an offence to communicate information, by signaling or otherwise, about the movement or disposition of troops and allowed for the imprisonment of persons committing disciplinary offences in internment camps.(59)

The following is Wilson’s account of how the regulations came to touch her life in the Arab High School in Birzeit. She recalls the moment when:

Everyone was discussing this new regulation requiring anybody who went anywhere after November 1st to have a permit, because the rebels were said to be forbidding all Arabs to get them. The boys were lamenting, because no buses would mean no ‘away’ football matches. Mary Naser said ‘if there are no buses, how shall we get rid of the cats?’. There were always three or four starveling cats, half wild, racing about the school kitchen and in and out of the girls’ dining room at meals. Every now and then the edict would go forth that they were too many, and a nuisance, so one would be popped into a sack and put on the bus when any of the staff were going into Jerusalem. The staff would see that the sack was open and the occupant let out at some village on the way, usually Ain Sinia …. The only non-Arab vehicle in the place was Miss Hulbert’s car, but Miss Hulbert was expecting to go away shortly on a three-month furlough. On the Thursday, she went into Jerusalem to investigate this question of permits.

After tea, Rika and I strolled up to her house to see if she was back. Standing in her garden you felt on top of the world. On the bare brown hilltops all round, the light and shadow were changing every hour of the day. The sirocco was blowing that afternoon, the scorching wind from the eastern deserts, making the distant Mediterranean seem a hard-blue band on the horizon and giving the white towns on the coastal plain the sharp outlines of a relief map: Ramleh, Lydd, Jaffa and Tel Aviv. Down on that plain, immigrant Jewish doctors with European reputations were working as chicken farmers because there were too many of them in Palestine to get practices, and here in Birzeit it was impossible to get any doctor whatever. At the best of times, before the ‘troubles’, it had meant sending six miles to Ramallah for one. It was not surprising that Miss Hulbert’s clinic and dispensary were patronized by peasants and rebels from far and near. Her only rule in connection with rebels was that they must not bring their rifles into the clinic with them; following the occasion when an armed warrior came to have his eyes treated and insisted on standing for the ‘drops’ with his beloved gun leaning against his shoulder, pointing straight into Miss Hulbert’s face. She was sure that when the drop went in he would jump and that might be the end of her, so after that there was a rule in the clinic, “Please leave your rifle at the door as you come in.”(60)

Wilson’s life experience during the Emergency Regulations might give us an account of the entrenched realities of politics, gender and law in Palestine: the intersecting political patterns and the normative contradictions ensured Wilson a basic space of agency and freedom. In the overlapping borders and limits imposed by the different systems of rules, she determined her space of identity and actions. In her diary, she does not hide her “belonging to both sides” and her language itself constitutes an inner space for ambiguities and contradictions. The most important real-life contradiction lies in her institutionalised political belonging. As the citation at the beginning of this article reveals, she claims to be both respected by the rebels and ignored by the Government. At first glance, her privilege consists in being able to comply both with the rules of the colonised state and of its indigenous resistance. Giving an account of her encounter with the rebels’ system of justice, she recalls an arbitration judgment arising from a neighbourhood dispute:

Old Abu Sulaiman was building a new house, and his neighbour, Nahum, complained that the wall of it stuck too far out into the road. On this particular night, a lorry-load of rebels happened to be passing through the village, and Nahum called them to arbitrate. What we heard was partly the arbitration and partly the opinions of other neighbours on the rebels being dragged into the matter at all.

Two nights later, while we were at supper, Miss Naser told us that a rebel judge, Abouji, had come into the village and was to try the case that night, upstairs in the school sitting-room. (Old Abu Suleiman was a distant relative of hers.) The whole table of us – Sitt Lulu, Sitt Vera, Sitt Mariam, Miss Naser’s sisters, Rika and myself – instantly decided to be present. Knowing the limited capacity of the school sitting-room, we cleared the grape-dish at record speed and trooped upstairs (…) [H]e pulled up the tight white trousers which he wore under the robe to show us the scars of wounds received from the British when he fought in an engagement at Deir Ghussani, not far from Birzeit, a few weeks before. He used to be connected with a cinema business in Jaffa, and before that in Iraq. He said the rebels were taking cine-pictures of their operations. Now he was directing one of their news-sheets. Five hundred copies of this were produced at a time, on type writers and duplicators (which probably accounted for the recent epidemic of vanishing typewriters from offices all over the country) (….) The rest of the staff told Rika and me that we should be quite safe to go about anywhere now that Abouji knew us. We only had to mention his name.(61)

Her presence at the rebel court assured her the protection of the indigenous community, fostering a sense of belonging which allowed her a safe haven and freedom of movement. Her controversial and continuously negotiated positioning is shown by her opinions on rebel justice. On the one hand, she sceptically recounts the administration of justice carried out by the Palestinian rebels in the context of the revolts, for example when she reports about the rumours spread during the revolt. On the other hand, her approval of a justice system more inclined to recognise gender equality and grounded in the celebration of women’s role in the revolt triggered her solidarity, based on a notion of women’s sisterhood. She reports how Ajoui, the rebel leader, said: “if all the rebels were killed except one woman (…) she still goes fighting for our rights”.(62)

Wilson’s admission to the court and her inclusion in the community fostered in her a sense of belonging and provided a location for the negotiation of her in-betweenness, that is, a cross-cultural space in which her belonging to the coloniser side faded into a contested terrain of continuous negotiations involved in the exchange of cultural performances. Homi Bhabha, in his introduction to The Location of Culture,refers to liminality as a transitory, in-between state or space, which is characterised by indeterminacy, ambiguity, hybridity, potential for subversion and change.(63)

Through post-colonial lenses, Wilson’s diary is read as a testimony of the entrenched realities of law, identity and gender in Mandatory Palestine. Wilson’s strategies of identification, representation and agency are conflated in her autobiographical account of overlapping spaces of colonial and anti-colonial systems of justice. Her use of her white privileged and female identity is negotiated within the intersubjective and collective experiences of the anti-colonial revolt. Her experience of the de facto martial law was one that made her invisible to and gave her substantial freedom from the rules of the Mandate authorities: it allowed her to be tolerated by the rebels, while at the same time she was not oppressed by their juridical order. Her privileged position relied on this ambivalent vacuum. She recalls, for example, that when the villagers had been forbidden by the rebels to ask for permits from the British as a form of political resistance, she was exempted from this rule by virtue of her (female) gender identity.

At the same time, Wilson claims to have been ignored by the Government, for example when she recalls that her gender allowed her to acquire a privileged status vis-à-vis the British authorities, as represented by the curfew pass granted by the colonial force. At a moment when the villagers of Birzeit could not leave their village, her ambivalent status of belonging to “both sides” allowed her to carry out work that was either endangered or largely prohibited by the Emergency Regulations. This can be seen on many occasions, such as when she performed those tasks – visiting prisoners,(64) posting mail, buying medicines, providing food reserve and acquiring materials for school activities(65) – that were necessary for the continued daily life of the school and the village. In these actions, a form of female solidarity grants Wilson the opportunity to travel under the informal female authority of the headmistress Naser and to bypass the authority of the British as well as of the rebels.

In this sense, her curfew pass comes to symbolise the blank space in which Wilson could act, avoiding the law and rules arising in the colonial space both from the oppressor and the oppressed. Wilson did not solve her dilemma about which side of the struggle she would belong to,(66) but opted for a pragmatic approach that made her able to use her gender and national identity to serve the direct needs of those in her surroundings who belonged to the same class. In several parts of her diary, she struggled with the notion of belonging to her own country;(67) sometimes she confronted the Palestinian rebels, pretending to be a member of the British troops in order to achieve unjustified advantages. When Wilson in her diary retells the stories of those encounters, she shows her conflicted sense of belonging: she acted in defence of the name of the British, of a “Britishness” that had been outraged. At the same time, she felt “honoured” by the Palestinians’ show of trust and acted against the British authorities. For example, at one British checkpoint, Arab men were searched at the entrance to Jerusalem. She recalls:

when, as the men rose to get out, a hairy brown hand came over my shoulder from behind and dropped a roll of pound notes into my lap. I stuffed them into the front of my dress and looked up to see which passenger it was who was honouring me in this way, but I couldn’t be sure. So, when they had all got in again I held my hand with the notes in it backwards over my shoulder … It was all right. I felt a single hand take them quietly.(68)

In this section on Wilson’s account of the Arab revolt, I have attempted to show how the role played by race, class and gender disrupts a homogenising narrative that sees the colonial struggle as a confrontation between coloniser and colonised. I have considered Wilson’s experience by focusing on how her gender and whiteness affected the relations between the individual, the community and the (Mandatory/colonial) state. In her case, the space of self-determination can be found in the blank spaces of collapsing systems of justice whose oppressive norms she was privileged enough to escape, either by virtue of her British identity or because of her female gender identity. Moreover, Wilson’s case might offer a case for an interracial form of resistance, such as might take place in the empire, since Wilson’s political stands were aligned more with those of her Palestinian colleagues than with those of the citizens and soldiers of her home country. Her curfew pass thus represents a small attempt at mutual cooperation and tells a forgotten story of interracial solidarity and resistance against the grain of law and privilege. In this, it offers socio-legal insights for today’s social justice struggle.

Conclusion

In this article, I have attempted to offer a more nuanced account of the British repression of the anti-colonial insurgency that took place in Palestine during the 1936-1939 Arab revolt. In particular, I have attempted to investigate how legal, anthropological and post-colonial approaches can be epistemologically and methodologically fruitful in questioning how women used their legal positioning and privilege in the (post)colonial context, in order to challenge and transform pre-constituted dichotomic legal narratives of the colonial encounter. In showing how issues of race and gender inform Wilson’s opinions and choices about whether and how to act during the Arab revolt, my aim was to give a more contextual, complex and relational account of the experience of law in the colonial “peripheries”, where, reconsidering Mbembe’s quote in the introduction to this article, the exceptional suspension of the institutional juridical order of the coloniser (Wilson’s pass) could open new ways for rethinking forms of “civilisation” (Wilson’s solidarity).

In order to achieve this goal, I engaged with two methodological approaches. Firstly, considering law as an artefact allowed me to link the materiality of its existence with the context in which it was lived: the curfew notice and Wilson’s curfew pass could thus narrate an untold tale of solidarity rather than hierarchy and of hybridity rather than identity, which more generally epitomises the possibility for a broader counter-narrative of the history of law. Secondly, considering Wilson’s diary as a source expanded the legal and historical framework of the legal history of women. Moreover, a reflection on women’s memoirs also allowed me to expand the discussion on legal subjects. Although Wilson was a citizen of the British Empire and a faithful supporter of the intrinsic fairness of the British legal system, her process of becoming a legal subject par excellence emerges from her own narrative as disturbed and challenged. Belonging to both sides, she showed a different kind of agency, an agency that subverts the initial meaning of the curfew pass, from a token of privilege to an instrument used to foster a transnational, contextualised and negotiated process of resistance.

Bibliography

Aliwood, S., ‘“The True State of My Case”: The Memoirs of Mrs. Anne Bailey 1771’, Law, Crime and History, Vol. 6, no. 1, 2016, 37.

Anghie, A., Imperialism, Sovereignty and the Making of International Law, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Anghie A., ‘Colonialism and the Birth of International Institutions: Sovereignty, Economy, and the Mandate System of the League of Nations’, New York University Journal of International Law and Politics, Vol. 34, 2002, 513.

Auchmuty, R., ‘Recovering Lost Lives: Researching Women in Legal History’, Journal of Law and Society, Vol. 42, no. 4., 2015, 34.

Bentwich, N.,‘The Legal System of Palestine During the Mandate’, Middle East Journal, Vol. 2, no. 1, 1948, 33.

Bentwich, N., The Mandate System, London, Longmans, 1930.

Bhabha, H.K., The Location of Culture, London, Routledge, 2004.

Batlan, F., ‘Legal History and the Politics of Inclusion’, Journal of Women’s History,Vol. 26, no. 4, 2014, 155.

Batlan, F., ‘Engendering Legal History’, Law & Society Inquiry, Vol. 30, no. 4, 2005, 823.

Berman P. S., Global Legal Pluralism: A Jurisprudence of Law Beyond Borders, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Chakrabarty, D., Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference, Princeton, NJ, Princeton University Press, 2000.

Charlesworth, H., and Chinkin, C.M., The Boundaries of International Law: A Feminist Analysis, Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2000.

Chiam, M., ‘Tom Barker’s “To Arms!” Poster: Internationalism and Resistance in First World War Australia’, London Review of International Law, Vol. 5., no. 1, 2017, 125.

Chiam, M., Eslava, L., Painter, G.R., Parfitt, R.S. and Peevers, C., ‘History, Anthropology and the Archive of International Law’, London Review of International Law, Vol. 5, no. 1, 2017, 3.

Chiam, M., Eslava, L., Painter, G.R., Parfitt, R. and Peevers, C., ‘The First World War Interrupted: Artefacts as International Law’s Archive (Part I)’, Critical Legal Thinking: Law and the Political, 15 December 2014, http://criticallegalthinking.com/2014/12/15/first-world-war-interrupted-artefacts-international-laws-archive/

Engle, K., ‘International Human Right and Feminism: Where Discourses Meet’, Michigan Journal of International Law, Vol. 13, 1992, 517.

Eslava, L., ‘The Materiality of International Law: Violence, History and Joe Sacco’s The Great War’, London Review of International Law, Vol. 5, no. 1, 2017, 49.

Heathcote, G., The Law on the Use of Force: A Feminist Analysis, Routledge, London, 2011.

Hughes, M., ‘From Law and Order to Pacification: Britain's Suppression of the Arab Revolt in Palestine,1936–39’, Journal of Palestinian Studies, Vol. 39, no. 2, 2010, 6.

Hughes, M., ‘The Banality of Brutality: British Armed Forces and the Repression of the Arab Revolt in Palestine, 1936-1939’, English Historical Review, Vol. CXXIV, no. 507, 2009, 313.

Kapur, R., Erotic Justice: Law and the New Politics of Post-Colonialism, London, Glasshouse, 2005.

Khalidi, R., Palestinian Identity: The Construction of Modern National Consciousness, New York, Columbia University Press, 1993.

Koskenniemi, M., From Apology to Utopia: The Structure of International Legal Argument, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Koskenniemi, M., The Gentle Civiliser of Nations: The Rise and Fall of International Law 1870-1960, Cambridge,Cambridge University Press, 2001.

Likhovsky, A., Law and Identity in Mandate Palestine, Durham, NC, University of North Carolina Press, 2006.

Mbembe, J.A., ‘Necropolitics’, Public Culture, Vol. 15, no. 1, 2003, 11.

Miller, R. (ed.), Britain, Palestine and the Empire: The Mandate Years, London, Ashgate, 2010.

Minh-ha, T., Women, Native, Other: Writing Postcoloniality and Feminism, Bloomington, Indian University Press, 1989.

Mohanty, C.T., Russo, A. and Torres, L. (eds), Third World Women and the Politics of Feminism, Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 1991.

Morton, S., States of Emergencies: Colonialism, Literature and Law, Liverpool, Liverpool University Press, 2013.

Naffine, N. and Owens, R. (eds), Sexing the Subject of Law, Sydney, Law Book Company, 1997.

Newton, F.E., Fifty Years in Palestine, London, Coldharbour, 1948.

Otomo, Y., ‘Searching for Virtue in International Law’in S. Kouvo and Z. Pearson (eds), Feminist Perspective on Contemporary International Law: Between Resistance and Compliance, Oxford, Hart Publishing, 2011.

Pappe, I., The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, London, Oneworld, 2006.

Porath, Y., The Emergence of the Palestinian-Arab National Movement: From Riots to Ribellion, Vol. 2, 1929- 1939, London, F. Cass, 1977.

Rajagopal, B., International Law from Below: Development, Social Movements and Third World Resistance, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Raynold, J., Empire, Emergency and International Law, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2017.

Sandberg, R., ‘Women’s Legal History: The Future of Legal History’, paper presented at the Doing Women’s Legal History Conference, Institute of Advanced Legal Studies, London, 26 October 2016.

Scott, J.W., Gender and the Politics of History, New York, Columbia University Press, 1988.

Swedenburg, T., Memories of the Revolt, 1936-1939 Rebellion and the Palestinian National Past, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1995.

Strawson, J., Partitioning Palestine: Legal Fundamentalism in the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict, London, Pluto Press, 2010.

Wright, Q., Mandates Under the League of Nations, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1930.

Legal Sources

League of Nations, Covenant of the League of Nations, 28 April 1919, available at http://www.refworld.org/docid/3dd8b9854.html.

Archives

Middle East Centre Archive, Saint Anthony’s College, Oxford.

The National Archive of the UK (TNA), Richmond.

* PhD student, Centre for Gender Studies, and affiliate of the Centre for the Study of Colonialism, Empire and International Law, SOAS, University of London, UK. Email pz4@soas.ac.uk

(1) Wilson, H.M., GB165-0302, Middle East Centre Archive, p. 16. Note that ‘School Year in Palestine’ is the TS account of Miss Wilson’s life as a teacher based on a detailed diary kept at the time.

(2) Strawson, J., Partitioning Palestine: Legal Fundamentalism in the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict, London, Pluto Press, 2010; Porath, Y., The Emergence of the Palestinian-Arab National Movement: From Riots to Rebellion, Vol. 2, 1929-1939, London, F. Cass, 1977.

(3) Although “real” martial law was never imposed in Palestine, through a series of Orders in Council and emergency regulations Britain imposed a “statutory” martial law, something in between a semi-military rule under civilian power and a full martial law under military power, one in which the army and not the civilian High Commissioner had the upper hand. In other words, it was a de facto and not de jure martial law. Martial law in English law implied the replacement of civilian power, in every administrative and judicial aspect of government within the whole country, by the military, acting not under any specific legal provision but on the principle that military commanders had the power and duty to take charge when all means provided for government under existing law have broken down. Short of this, if the police were unable to preserve law and order, the military could always be called in to assist civilian powers, to perform so-called “duties in aid of civilian power”. In this case, however, while the military were theoretically subordinated to civilian power, in actual fact military officers were in sole command over their own forces and disposed of them according to military orders or to the best of their judgement. During such a period in a colonial context, legal doctrines were unclear. As such, Mandatory Palestine became a zona franca where different interpretations of legal doctrines and the practice of insurgency repression – after the experience in India and Ireland – could be tried. Hughes, M., ‘The Banality of Brutality: British Armed Forces and the Repression of the Arab Revolt in Palestine, 1936-1939’, English Historical Review Vol. CXXIV, no. 507, 2009, p. 318-319; Morton S., States of Emergencies: Colonialism, Literature and Law, Liverpool, Liverpool University Press, 2013, p. 173-183; See also, in the context of the home front in World War One, Rubin G.R. and Moore C. R., ‘Emergency Powers in Britain in World War One: “Corporatist” Law or a Government that “Bluffed with Confidence”?’ in David Deroussin (ed.), La Grande Guerre et son droit,Paris, LGDJ, 2018, p. 323-329.

(4) Rajagopal, B., International Law from Below: Development, Social Movements and Third World Resistance, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2003.

(5) Wilson H.M., GB165-0302, p. 16.

(6) Anghie, A., Imperialism, Sovereignty and the Making of International Law, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2005; Koskenniemi, M., The Gentle Civiliser of Nations: The Rise and Fall of International Law 1870-1960, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2001; Berman, P. S., Global Legal Pluralism: A Jurisprudence of Law Beyond Borders, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2012.

(7) Rajagopal B., International Law from Below.

(8) Chiam, M., ‘Tom Barker’s “To Arms!” Poster: Internationalism and Resistance in First World War Australia’, London Review of International Law, Vol. 15, no. 1, 2017.

(9) Morton S., States of Emergencies, p. 1-11.

(10) Ibid., p. 173-183.

(11) The terrorist bands I am referring to were the Irgun and the Haganah. See Pappe I., The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, London, Oneworld, 2006.

(12) Strawson, J., Partitioning Palestine.

(13) Wilson, H.M., GB165-0302, p. 2.

(14) Morton S., States of Emergencies, p. 1-11. For the most comprehensive work on the state of exception (in theoretical and historical terms) see Agamben, G., State of Exception, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2005. I do not engage with Agamben in any detail in this article due to space constraints. However, his reflection on the state of exception as the ground between the legal and the political is the underlying assumption for a methodological and epistemological enquiry into Hilda Wilsons’s diary as a useful historical source shedding light on women’s legal history.

(15) Batlan, F., ‘Engendering Legal History', Law & Society Inquiry, Vol. 30, no. 4, 2005.

(16) Mbembe J.A., ‘Necropolitics’, Public Culture, Vol. 15, no. 1, 2003, p. 24.

(17) Hughes, M., ‘From Law and Order to Pacification: Britain's Suppression of the Arab Revolt in Palestine,1936–39’, Journal of Palestinian Studies, Vol. 39, no. 2, 2010.

(18) CO 323.1396.8, The National Archive (TNA).

(19) Unfortunately, there is no further reference to Wilson’s sister in the archival source considered. Further research on Wilson’s family history might in this sense be desirable.

(20) Anghie A., ‘Colonialism and the Birth of International Institutions: Sovereignty, Economy, and the Mandate System of the League of Nations’, New York University Journal of International Law and Politics, Vol. 34, 2002, p. 115-136.

(21) Palestine was part of those “certain communities formerly belonging to the Turkish empire [which] have reached a stage of development where their existence as independent nations can be provisionally recognised … until such time as they are able to stand alone” (par. 4, art. 22). Nevertheless, “the principle that the well-being and development of such people form a sacred trust of civilisation” should apply (par. 1, art. 22). League of Nations, Covenant of the League of Nations, 28 April 1919, available at http://www.refworld.org/docid/3dd8b9854.html.

Legal scholarship on the Mandate system includes: Wright, Q., Mandates Under the League of Nations,, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1930; Bentwich, N., The Mandate System, London, Longmans, 1930; Miller, R. (ed.), Britain, Palestine and the Empire: The Mandate Years,London, Ashgate, 2010.

(22) Rajagopal B., International Law from Below, p. 51.

(23) Kapur R., Erotic Justice: Law and the New Politics of Post-colonialism, London, Glasshouse, 2005, p.21.

(24) Ibid.

(25) Eslava, L., ‘The Materiality of International Law: Violence, History and Joe Sacco’s The Great War’, London Review of International Law, Vol. 5, no. 1, 2017.

(26) Batlan, F., ‘Engendering Legal History’; Anghie, A., Imperialism, Sovereignty and the Making of International Law,; Batlan, F., ‘Legal History and the Politics of Inclusion’, Journal of Women’s History Vol. 26, no. 4, 2014.

(27) Scott, J.W., Gender and the Politics of History, New York, Columbia University Press, 1988; Naffine, N. and Owens R. (eds), Sexing the Subject of Law, Sydney, Law Book Company, 1997; Otomo, Y., ‘Searching for Virtue in International Law’ in Kouvo, S. and Pearson, Z. (eds), Feminist Perspectives on Contemporary International Law: Between Resistance and Compliance, Oxford, Hart Publishing, 2011.

(28) Charlesworth, H. and Chinkin, C.M., The Boundaries of International Law: A Feminist Analysis, Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2000; Heathcote, G., The Law on the Use of Force: A Feminist Analysis, London, Routledge, 2011; K. Engle, ‘International Human Right and Feminism: Where Discourses Meet’, Michigan Journal of International Law Vol. 13, 1992.

(29) Chakrabarty D., Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference, Princeton, NJ, Princeton University Press, 2000.

(30) Kapur, R., Erotic Justice, p. 20.

(31) Chiam, M., Eslava, L., Painter, G.R., Parfitt, R.S. and Peevers, C., ‘History, Anthropology and the Archive of International Law’, London Review of International Law, Vol. 5., no. 1, 2017, p. 3.

(32) Ibid.

(33) Chiam, M. ‘Tom Barker’s ‘To Arms!” Poster’.

(34) Koskenniemi, M., From Apology to Utopia: The Structure of International Legal Argument, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2006, p. 21-25.

(35) Chiam, M., Eslava, L., Painter, G.R., Parfitt, R. and Peevers, C., ‘The First World War Interrupted: Artefacts as International Law’s Archive (Part I)’ in Critical Legal Thinking: Law and the Political, 15 December 2014, http://criticallegalthinking.com/2014/12/15/first-world-war-interrupted-artefacts-international-laws-archive/

(36) Foucault, M., The Order of Things, cited in Chiam, M., et al., ‘The First World War Interrupted’.

(37) Aliwood, S., ‘“The True State of My Case”: The Memoirs of Mrs. Anne Bailey 1771’, Law, Crime and History, Vol. 6, no. 1,2016.

(38) Biographic sheet of Hilda M. Wilson, GB165-0302, Middle East Centre Archive.

(39) Aliwood, S., ‘“The True State of My Case”’.

(40) Wilson, H.M., GB165-0302, p. 3.

(41) Ibid., p. 1-3.

(42) Auchmuty, R., ‘Recovering Lost Lives: Researching Women in Legal History’, Journal of Law and Society, Vol. 42, no. 1, 2015, p. 34-52.

(43) Ibid., p. 34-35.

(44) Kapur, R., Erotic Justice, p. 21.

(45) Biographic sheet of Hilda M. Wilson.

(46) Wilson, H.M., GB165-0302, p. 1.

(47) Hughes, M., ‘From Law and Order to Pacification’.

(48) Newton, F.E., Fifty Years in Palestine, London, Coldharbour, 1948; Swedenburg, T., Memories of the Revolt, 1936-1939 Rebellion and the Palestinian National Past, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1995; Likhovsky, A., Law and Identity in Mandate Palestine, Durham, NC, University of North Carolina Press, 2006.

(49) Hughes, M., ‘The Banality of Brutality’.

(50) Palestine Royal Commission Report Presented by the Secretary of State for the Colonies to Parliament by Command of His Majesty, July 1937, London, His Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1937. See also Miller, R. (ed), Britain, Palestine and the Empire.

(51) Newton, F.E., Fifty Years in Palestine; Strawson, J., Partitioning Palestine.

(52) Wilson, H.M., GB165-0302, p. 1.

(53) Bentwich, N.,‘The Legal System of Palestine during the Mandate’, Middle East Journal, Vol. 2, no. 1, 1948.

(54) Wilson, H.M., GB165-0302, p. 2.

(55) Emery, G.B., GB165-0099, Middle East Centre Archive.

(56) Wilson, H.M., GB165-0302, p. 54.

(57) Hughes, M., ‘The Banality of Brutality’.

(58) Ibid.

(59) Ibid.

(60) Wilson, H.M., GB165-0302, p. 15-16.

(61) Ibid., p. 15.

(62) Ibid., p. 14.

(63) Bhabha, H.K., The Location of Culture, London, Routledge, 2004.

(64) Wilson, H.M., GB165-0302, p. 38.

(65) Ibid., p. 18-20.

(66) For example, she is not able to trust the news about British brutalities in Palestine – which are now well documented – and writes about this: “A typical rumor which Rika and I collected six times over in the course of a few months, concerned a party of British troops engaged in punishing a village (a different village every time) for harboring rebels. They were said to have picked out the able-bodied men and made them dig a long trench, then shot them, so that their bodies fell neatly into the trench and there they were, buried. Almost equally persistent was a yarn about British troops tearing out the nails of Arab prisoners during the siege of the old city of Jerusalem. This week, Birzeit circulated a rumor to the effect that 15,000 rebels had driven the British army out of Jerusalem. Also, that one of the sacred buildings in the Temple area had been damaged by gun-fire. This I believe had some foundation of truth”. Ibid., p. 11.

(67) For example, in the reported case of looting by the British troops, Wilson, H.M., GB165-0302, p. 41. Another time, one night in mid-March the rebels came into the girls’ school. In this regard, Wilson writes: “The men turned towards me, and one of them asked, ‘Have we reason to be afraid of this lady? Suppose she telephones?’ Before I could speak in any language, Sitt Naomi burst out with voluble assurances that of course I would never dream of telephoning and that they had nothing to fear from me whatever. ‘She is so loyal to the Arabs that the British hate her face!’ which didn’t seem to leave much more to be said.” Ibid., p. 53.

(68) Ibid., p. 13.