Jo Spiller, ‘A Fair Field and No Favour’

Abstract: This paper illustrates how turning to art rather than focusing solely on legal reform can form part of an alternative response to gender inequality that allows for deeper understandings of social (in)justice. We show how the Scottish Feminist Judgments Project – a collaborative endeavour by legal academics, practising lawyers, judges, artistic contributors and representatives from the third sector – can offer those who engage with our art the experience of hearing and seeing law in different ways. More specifically, we explore how art can open law up to scrutiny, render vivid the impact of legal decisions, and create richer and more democratic communities of understanding. At the same time, by discussing knowledge differentials and the quandaries of creating art ethically, we also highlight some of the challenges involved in engaging in artistic-legal collaboration.

Keywords: Art, Activism, Feminism, Justice, Law, Scottish Feminist Judgments Project

1. Introduction

Feminist theories of judging are in the midst of creation and are not and perhaps will never aspire to be as solidified as the established legal doctrines of judging can sometimes appear to be.(1) As part of a global endeavour to rewrite key legal cases from a feminist perspective,(2) the Scottish Feminist Judgments Project (SFJP) has produced an edited collection of 16 feminist judgments, with accompanying expert commentaries, followed by reflective statements about the process of rewriting their cases from our 19 feminist judges.(3)

In line with other FJPs, in whose footsteps we followed, our aims in the SFJP were to demonstrate the difference that perspective makes in legal reasoning, legal storytelling, and decided outcomes; and to expose how feminist perspectives can highlight the gendered impact of seemingly neutral legal concepts. The ground-breaking work begun by the Women’s Court of Canada, who published their feminist judgments on Canadian equality law in 2008, fundamentally challenged and exposed the implicitly patriarchal construction of legal concepts and techniques of legal reasoning, reimagining the craft of judgment writing itself. Their work provided a platform for subsequent FJPs to emerge, and while each produced its own networks and outputs, they also became part of an increasingly intersectional, global, collaborative and community building enterprise. As a result of these combined efforts, rewritten feminist judgments have become more familiar – at least amongst academics – and perhaps, in that sense, less threatening or subversive. But while the fundamental premises and ambitions shared by this growing collective of FJPs may have become more unexceptional within the legal academy, the extent to which they have still been encountered as ‘surprising’ and ‘challenging’ by practitioners and policy-makers within their own jurisdictional contexts should not be underestimated. At the same time, it is also true to say that – standing on the shoulders of feminist fore-sisters – FJPs have, over time, been able to find space to become more confrontational and dissident in distinctive ways: by pushing beyond conventional FJP judging methods,(4) resisting the chronological constraint, to which earlier FJPs agreed, to be bound by the law as it stood at the time of original judgment,(5) challenging traditional sources of law,(6) or troubling jurisdictional boundaries.(7) Large-scale projects are now ongoing in India and Africa, where colonial structures and geographical challenges require creative management to enable the realisation of new kinds of FJPs.(8)

One of the ways the SFJP sought to push beyond the core objectives of well-established preceding FJPs was by communicating its feminist ambitions through innovative techniques and methods, designed to reach broader, less specialist audiences than those usually targeted by FJPs (legal academics, legal professionals and students). In this article, we explore the methodological journey of the SFJP, focusing in particular on the choice to integrate an artistic strand as a core part of the project – something that, as yet, has not been attempted in other FJPs.

Inspired in part by the Northern/Irish FJP’s use of theatre and other creative media in their methodology, and their inclusion of a poem at the start of their edited collection,(9) we were keen in the SFJP to use artistic methods in a more expansive way, to reach out to a wider constituency, and enable a diverse range of communities to engage with law. We did this through collaboration with a group of eight artists: Alison Burns, Rachel Donaldson, Jill Kennedy-McNeill, Sofia Nakou, Jess Orr, Becky O’Brien, Jo Spiller and Jay Whittaker.(10) Each artist worked with legal academics to comment critically on a specific case, or on the project as a whole, from a feminist perspective, and from within their own medium. To assist in developing their contributions to the project, all SFJP contributors – academic and artistic – were invited in the early stages of the project to take part in an “image-based” theatre workshop, run by Active Inquiry, a community theatre company in Leith.(11) The aim of the workshop was to provide a space in which to engage with concepts like “feminist” and “judgments” in a more embodied way than some of us – particularly those of us working mainly with text – might be familiar or comfortable with. By physically embodying law and legal concepts through gestures and images, our contributors were guided to show in an immediate and visually arresting way how legal norms and concepts are, or can become, powerful and persuasive but also are, ultimately, open to challenge, resistance and transformation. This was also a space in which we encouraged reflection on the process of ‘judging’ in all its forms, both to prepare writers for the task of re-imagining their selected cases and to spark a dialogue about perspective across academic and artistic contributors.

All of the artistic works produced for the SFJP can be accessed via a virtual exhibition hosted on the SFJP project website,(12) and a number of the pieces are discussed and depicted in the following sections. The artwork has been shown in a variety of forums and public spaces, including the Scottish Parliament, Mount Florida Gallery and Studios (Glasgow), South Block (Glasgow); and it was exhibited in Old College (Edinburgh) for the duration of the 2019 Fringe Festival and at Temperance Café in Leamington Spa during the 2019 ESRC Festival of Social Science. A travelling version of the exhibition has also been shown to attendees at a wide variety of presentations and training events linked to the project – including events hosted at the Crown Office, Scottish Parliament, Faculty of Advocates, Glasgow Women’s Library, Annual Law Society of Scotland Conference, and RebLaw Conference 2019 – and has been featured at high-profile public events marking the centenary of women’s participation in the legal profession.

Following the completion of the edited collection, we also took the SFJP on tour – by bicycle – directly to law school classrooms across Scotland. Susan B Anthony is said to have observed that the bicycle “has done more to emancipate women than any one thing in the world”.(13) Its ability to provide independence of movement to women and its setting in motion an aesthetic liberation from the restrictions of ‘conventional’ feminine dress has ensured that the bicycle has continued to represent a symbol for women’s freedom and empowerment since. To celebrate this history and raise funds for three charities connected to cases addressed in the project (Rape Crisis Scotland, Scottish Women’s Aid and Scottish Trans Alliance), the authors – together with allies of, and some fellow contributors to, the SFJP – cycled over 200 miles across Scotland to deliver six half-day workshops with students in Edinburgh, Glasgow, Dundee and Aberdeen, where the SFJP travelling exhibition was also on display.(14) As we have discussed elsewhere,(15) those workshops supported students in developing the skills of critical analysis required to re-imagine their own feminist judgments, giving them an opportunity to inhabit the space of a feminist judge by crafting sections of an alternative decision. With help in particular from our SFJP artists Sofia Nakou, Jay Whittaker and Jess Orr, we were also able to encourage students to use artistic media – imagery, found poetry and creative writing – to engage with cases and their legacies on law and life in new, and challenging, ways.

In this article, we reflect on the reasons why we developed this artistic strand of the project, and how successful we were in achieving our ambitions, sharing frankly the shortcomings of our attempts in the process. In the section that follows, we explore the ways that law as a closed, specialist body of knowledge has dismissed non-textual and non-legal knowledge; but how the critical perspectives offered by feminist academics and judges continue to highlight the importance of ‘subjective’ knowledge and artistic methods in challenging legal knowledge production. We then move on, in section 3, to examine what these ‘subjective’ perspectives on law and justice looked like in practice in the SFJP by presenting some of the work of our artists. Here, we show how our creative collaborators helped us to push the boundaries of what constitutes effective critical legal analysis, to develop a different sort of legal aesthetics, and to visualise the impact and legacy of legal decision-making in the so-called ‘real world’. We also present a thematic analysis of the feedback received from public and student audiences who viewed the art in a variety of settings. Finally, in section 4, we discuss some of the methodological, ethical and practical challenges we faced in designing and executing our project in this way, including the dangers of instrumentalising artistic work. We draw on feedback offered to us by both the artists and feminist judges who participated in the project to reflect on how we might have better met some of these challenges. We end by concluding that while art can speak about law in profound and perspective-changing ways, it is much more difficult for art to speak to law – or rather for law to hear art, since legal concepts, processes and outcomes appear relatively untouched by ‘external’ knowledge practices. The discovery that – in some respects at least – our project still reflects this acoustic separation was not entirely surprising, but it is a source of regret nevertheless. Despite this, we remain optimistic that, in opening up the idea of law, and illuminating starkly its wide ranging and deeply felt impacts, FJPs and other critical social justice projects can benefit substantially from the powerful insights that are generated by artistic-legal collaborations.

2. Art, law and justice: a matter of perspective?

In this section we examine the textual basis of law, and the ways in which non-textual and non-specialist sources have become peripheral to our legal knowledge production, before going on to explore how we might go beyond legal text and method, and employ ‘subjective’ knowledge and artistic methods to interrogate ‘objective’ law.

i. Law and legal language: beyond text?

Specialised written texts – rather than visual and other sensory experiences – have become the central source of law, as well as the method by which law is studied and practised. Drawing on work by Peter Goodrich and Costas Douzinas, amongst others, Linda Mulcahy explains this valorisation of legal text, mapping a series of historical moves that have led us to exclude non-textual images from ‘real law’, and to see law and the image as dichotomous.(16) Written text, she argues, has become venerated in law, as the appropriate way in which to understand, analyse and produce knowledge, and to keep law separate from the extra-legal, including the terrain of emotions and morals, as well as the visual, the sensual,(17) and, we would add, the artistic more generally. That lawyers continue to be strongly invested (consciously or unconsciously) in the rigid separation of law from non-law is evident in myriad ways, and often reproduced and naturalised in how we as legal academics teach and examine our students; indeed, many students in our SFJP workshops expressed scepticism, followed by surprise, that they could learn anything about the law through an artistic perspective.

Notwithstanding the specialised textual basis of law, sometimes legal language can be alienating, if not for professionals, then certainly for first year law students, as well as those who are law’s subjects more generally. As John Conley and William O’Barr observe, legal discourse is “far removed from the language of ordinary people [and] tends to transform or simply to ignore the language of litigants themselves”.(18) Desmond Manderson reflects on the law’s reliance on text, and fetishisation of words, in a typically more lyrical way: “Law continues to write as if, like the Victorians, it’s being paid by the word… The glorious length of the law is an inducement to sinking but an impediment to thinking”.(19) But it is not just this proliferation of technical words that Manderson bemoans, it is also the ways that legal words can be “tyrannically linear” in leading us to a particular result. As he puts it, “they direct us to one conclusion to the exclusion of all others; they close options rather than open them…forcing us to submit to [their] logic.”(20) Creative work can, then, help us “hear a language we do not speak”(21) and “care less about abstractions than individual lives”.(22)

It is partly for these sorts of reasons that socio-legal and other scholars have turned to artistic, particularly visual, renditions of law in an effort to understand law’s place in our lives, and to “see what law looks like from the perspective of others unencumbered by text”.(23) Opening up law to critical scrutiny in this more democratic, accessible way has the effect of what we might describe as rendering the strange more familiar and vivid, or disrupting the “structuring capacity of law”,(24) so that our moral imaginations are not hampered by the strict constraints of legal frameworks and language.(25) Both art and law are what Manderson calls social facts, and we can learn to talk about law “using the whole chocolaty [sic] language of our social world – art, poetry, children’s books, movies, newspapers, the lot”.(26)

The ambition of the SFJP was not (solely) to use art to critique the law, but also to push beyond the limits of the legal imagination to show how central concepts of law, and the idea of law itself, can become productively corrupted or contaminated by the aesthetic. Our creative contributors produced art as a way of illuminating the injustices of law through media that are more viscerally accessible and deliberately provocative. Although in the SFJP we have largely preserved a distinction between art and law, it is important to note, as we discuss here, that this does not mean we subscribe either to the idea that law is and should be objective, or that art is and should be neatly separable from law. Indeed, in Jay Whittaker’s found poems, which we return to in section three, the very text of law itself becomes art, powerfully and provocatively illuminating how the apparently abstract, neutralising language of law functions as a conservative, heteronormative and gendered tool of social control.

ii. Objective law and subjective art: critical companions or antagonistic adversaries?

Using art to ‘translate’ discourses such as law into more accessible forms of communication risks a number of unintended effects. One such effect is ossifying a perception that law is – and should be – the pinnacle of neutrality, objectivity and impartiality, while art is its opposite – unfettered, excessive, and subjective. In other words, law remains a closed system of expert knowledge, untouched by the capricious creativity of the arts. At least one of our feminist judges shared this perception, commenting on the SFJP artistic strand that “it was a nice touch to have the input but it did not impact on how I carried out my task that I am aware of”.

Regarding art and law as fundamentally opposed or closed off from each other supports arguments that favour maintaining the distinction between the two as rigidly as possible. For example, J Harvie Wilkinson argues that “Art and Law are created through distinct processes and serve different purposes. Law also commands the full power of the state... These differences make it dangerous for law to imitate art’s subjective impulses and emotions”.(27) But while art and law can and do serve different purposes, and the law wields state power in a way that art does not, art can help us reflect on the power of law; and, as we shall see, it is sometimes art’s imitation of law, such as through the found poetry of Jay Whittaker, that starkly illuminates the choices made by judges when applying the law. In that sense, art does have the potential to expose the messy entrails of a supposedly coherent body of law.

Wilkinson, himself a judge in the US, builds his argument upon the assertion that judges are engaging either in ’discovery’ or ‘creation’.(28) Unlike the judge, he says, who is merely an “observer” making discoveries, an artist can “do as he [sic] pleases with his creations. But only a creator possesses such authority”.(29) This is a debate perhaps most recognisable in the context of the US, where judges are often categorised as textualists, who do not look at intent but only the ‘objective’ plain meaning of the words of the Constitution; originalists, who try to discern and apply the original meaning or intent behind the Constitution; and those who treat the Constitution as a ‘living tree’, open to reinterpretation given changing social contexts and mores. The first two approaches lend themselves towards an ‘objective’ understanding of law, the third to a more contextual or subjective conception.(30) This particular debate is not transferable to all judicial contexts, though it highlights the somewhat idiosyncratic recognition (and indeed celebration) in Scots law of the ability of judges to develop the law in line with societal change.(31) Nonetheless, Wilkinson’s framework supports the assumption that law is objective, art subjective, and never the twain shall meet.(32) This is far from axiomatic for feminists who wish either to question the very idea that law ever could or should be entirely objective, or to challenge supposedly rigid conceptual dichotomies such as objective/subjective.

On the former question – of whether law can and should be objective or subjective – Wilkinson is emphatic that “transposition of artistic licence to judicial latitude is elitist in the extreme”.(33) This is, he says, because the polity has not consented to being governed by the arts. Since artistic sensibilities are the result of a single unrepresentative artist’s personality and impulses, while law is the product of democratic collective decision-making, “it requires a certain chutzpah, whether conscious or not, to assert that empathy, self- expression, or subjectivity should be used by judges in reaching legal determinations”.(34) While Wilkinson does not dispute the importance of judicial recognition of social diversity, this comes not from importing individual judges’ experiences into their decision-making in a way that distracts from a neutral interpretation of law, but rather from “aggregating people's backgrounds democratically”. For him, allowing judges to express their own perspectives subverts the democratic process of law making, and merely reflects the idiosyncrasies of individuals’ backgrounds and experiences.(35)

Wilkinson’s analysis here relies, however, on an over-individualist account of art and creative enterprises. Think, for example, of the Turner Prize 2019, which was given to all four of the final nominees who had agreed amongst themselves that they would not accept the prize unless awarded it jointly.(36) Equally, he may present an overstated description of the democratic and collective nature of law-making. But it is his position on the place of empathy and perspective in judging that seems most at odds with the raison d’etre of FJPs.

Wilkinson may be right that it is not background or individual characteristics that grant judges the power to resolve disputes,(37) but these matters do affect how a judge will see the facts before them, and the decisions they make as to which facts are relevant, which rules of evidence and which precedents apply, and how to apply them. In short, it is a judge’s individuality and background that informs how they resolve disputes: “Like any text, legal or fictional, how we read [a] story depends on who we are, and on the stories, long ago, we read”.(38) This means that even where a law is as clear as it could possibly be, it cannot ever be completely neutral, or represent a ’view from nowhere’; there will be room for different perspectives in its application to a given set of facts – and even in deciding what constitutes a fact.(39) As Justice L’Heureux-Dubé has put it, “Judging can be described as the piecing together of a story which will never be more than partial and will always reflect the legal rules which govern its telling”.(40) These claims lie at the heart of feminist judgments projects. They also, of course, form the bedrock of broader critical scholarship, which has pointed out that the idea of a single, objective viewpoint will inevitably reproduce – yet also mask – the orthodoxy of a classed, racialised and gendered “flesh and blood” decision-maker.(41)

Wilkinson claims boldly that “Law is not in the eye of the beholder”.(42) But for those engaged in FJPs, that assertion emerges as significantly less clear-cut. Whilst our feminist judges could not change existing law, they could – and of course did – highlight the discretion afforded to, and exercised by, legal decision-makers, showing how in practice law can indeed be in the eye of the beholder. This insight was also captured well by some of the SFJP artistic work, especially that work which, as we discuss below, highlights the importance of perspective. As such, law and art might both be said to be subjective; and, following critical scrutiny, they appear to have a good deal more in common than Wilkinson would have us believe.

Feminists, particularly those informed by postmodern and poststructuralist perspectives, have also questioned whether categories such as objective/subjective are as dichotomous as they appear, arguing that law is a much more open and porous system than we might think. One potential consequence of this is that art can enter and disrupt law from the inside. For instance, in another context Donna Haraway has celebrated the potential for “pleasure in the confusion of boundaries”(43) and “transgressed boundaries, potent fusions and dangerous possibilities”.(44) For her, it is important to try to see things from various vantage points simultaneously: “Single vision produces worse illusions than double vision or many headed monsters”.(45) This requires attention to “multiple consciousnesses” which, as Mari Matsuda explains, requires deliberate attention to the subjective – “to see the world from the standpoint of the oppressed”. (46)

iii. Just(ice) perspectives?

Even where a particular judge takes the view that perspective does matter, and is not just useful but central to decision-making, Reg Graycar has argued that substantive legal tools and doctrines have proven almost impervious to feminist challenge, remaining anchored in the white, middle-class, male perspective that developed them.(47) Consequently, judges who do not fit this mould are sometimes accused of bias when they try to incorporate a marginalised perspective or inclusive principle in their reasoning.(48) Acknowledging the importance of perspective and life experiences, Sonia Sotomayor, the first Latina woman Supreme Court Justice in the US said: “our experiences as women and people of color affect our decisions. The aspiration to impartiality is just that – it's an aspiration because it denies the fact that we are by our experiences making different choices than others”.(49) More pessimistically, Sandra Berns posits that it is impossible for an African-American judge to fully speak simultaneously as ‘other’ and with full legal authority.(50) It is here that using tools other than those of the ‘masters’(51) – including artistic responses to, and depictions of, law – can help dismantle engrained ways of seeing, and even the very notion that there are correct ways of seeing at all; how we see things is affected by what we know, and what we believe.(52) This also calls to mind the insistence of Patricia Williams that “It really is possible to see things – even the most concrete things – simultaneously yet differently”.(53)

In the SFJP, then, using art meant not only engaging the public more directly in seeing the impact and consequences of law more directly, but also enabling a sustained focus on particular instances of legal decision-making, rather than on universal legal rules of general application.

The view that ‘objective’ law should be separate from ‘subjective’ art also illuminates a tension between those who see law as devoid of empathy with legal subjects, and those who value compassion and acknowledging one’s own perspective and positionality in legal decision-making. Many feminists – including feminist judges – have also argued that good judging involves a degree of empathy that someone with an unreflexive view of law’s objectivity could not countenance. Some have even observed that failing to acknowledge the importance of the capacity for compassion leads to an impoverished vision of what justice can and should entail; Justice L’Heureux-Dubé cites Canadian Chief Justice Dickinson as saying: “Compassion is not some extralegal [sic] factor magnanimously acknowledged by a benevolent decision-maker… compassion is part and parcel of the nature and content of that which we call ‘law’”.(54) Indeed, this has been recognised in England and Wales, where the Judicial Skills and Abilities Framework lists empathy as one of the required competencies of judicial office holders.(55)

What is being argued for here, then, is a compassionate and just legal system that puts sensitivity to the diversity and particularity of human experiences, especially with respect to those who are most different to the powerful majority, at its core. That in turn entails a broader focus than simply increasing diversity on the bench or in our universities, or forming equality and diversity committees, or indeed asking those who are ‘different’ from ‘us’ to bear the yoke of responsibility for reminding ‘us’ to be sensitive to that difference. Instead, we must ask all of those who have legal decision-making (and legal educative) power to be open to asking challenging questions, such as what is meant by difference, how that difference has come to be, and what difference that difference does, and should, make.

Centring the untold stories of the oppressed and marginalised, and revealing the under-represented narratives and missing social histories in original judgments, were key aims for feminist judgments writers and artists alike in the SFJP. In bringing art and law together in one project and attempting to see legal judgments from various perspectives simultaneously, we hoped to lay bare both the raw power of law and its ‘real-world’ effects, as well as the tools and techniques at its core that might be open to reworking. We found, as Mulcahy has put it, that art can “reveal what the elegantly written legal text does not about the violence of law… the result is that the image has the potential to reveal a ‘multiplicity of othernesses and differences’ which are for the most part silenced in texts”.(56) Weaving together rewritten judgments and creative responses blurred these methodological boundaries, offering up a less compartmentalised challenge to the power of law, and highlighting the synergies in purpose, approach and outcome that defy the ‘objective law, subjective art’ distinction.

In the next section we show how the work produced by the SFJP artists rendered vivid to a broader public audience the multiplicity of silenced “othernesses and differences” at play in the original judgments that were rewritten for the project. We also explore how opening up the law in this way created space for different perspectives and communities of understandings to develop which might then, in turn, help motivate and effect social change.

3. Art: critique, community, change

Seeking to question and disrupt the neat boundaries that the law often tries to construct for itself, between subjectivity and objectivity, each of the SFJP artists worked in their own medium to draw attention in arresting, visceral and radical ways to the human implications and impacts of legal decisions, as well as the limited ability of judges to offer true ‘resolution’. In doing so, their work mapped onto a wider ambition to cultivate new critical perspectives and consciousness about the power of law and its potential to create social change.

i. Rendering vivid the impact of law

At the core of any feminist judgment project is a commitment to bring to the fore gendered narratives and contexts that had been silenced or marginalised in the original judgment, and so for judgment-writers and artists alike, their task involved a process of excavating and imaginatively reconstructing perspectives that ‘humanise’ the legal. But, in respect of their form, feminist judgments projects have also consciously submitted themselves to certain existing conventions that, no matter how flawed and restrictive they may be, purchase a sense of ‘credibility’ amongst the legal practitioners at whom they are often targeted.

By contrast, the artistic form offers up an alternative set of critical and communicative tools with which to disrupt received wisdom, tell challenging new stories, and remind us both of law’s effects and its affects. As Oren Ben-Dor puts it, there is “an uncanny refusal by art to be tamed” into ways of making sense, and it is “valuable precisely because of that refusal”.(57) This operates often at a visceral level – art has the power to “speak to the emotions”, “short-circuit reason and enter the soul”,(58) including by framing the issues with which legal decision-makers engage not solely as issues of right, conflict, precedent and order, but “as questions of sympathy and vulnerability”,(59) in and beyond the judgment.

The most obvious examples of this in the SFJP context come from Jay Whittaker’s four poems. These were inspired by the case of Drury v HM Advocate,(60) rewritten in the project by Claire McDiarmid, in which a female victim, Marilyn McKenna, was brutally murdered by a former partner who, the court concluded, was entitled to put to the jury a defence of provocation by sexual infidelity – a defence historically rooted in jealousy and ownership of women that might be thought inappropriate for contemporary socio-sexual mores.(61) In doing so, the court confirmed that it remained open to the jury to conclude that the victim owed the accused an ongoing duty of fidelity despite their estrangement and that this duty, when ‘breached’, could operate to reduce the culpability of a homicidal rage. These issues are explored in her first poem, 'Provocation'.

Provocation

Ordinary wickedness

of heart

slapped herreasonable frenzy

a mere man

lost controlclaw hammer killer

precisely

struck herbrute retaliation

overwhelming

blunt forcefacial bones

tooth sockets

act faithfulseven blows

act depraved

a disproportionate fidelity

Here, Whittaker relies exclusively on words drawn from the original Drury judgment to create a found poem that generates a very different sort of provocation: one in which the reader cannot help but be confronted with the violence not only of the accused’s actions but of the law’s response in condoning it; we are left to wrangle with the jarring juxtaposition of detached legal vernacular and the brutality experienced by Marilyn McKenna.

In two further poems produced for the SFJP, Whittaker reflects further on the absent presence of Marilyn McKenna, both in the original judgment in Drury and in the ‘real world’ beyond. In ‘Not Here’, she draws attention to the ways in which legal argument in the case disguised and neutralised the violence and the human tragedy that resulted. She highlights the vulnerability of the victim and the inability of judicial logics to fully take on board that vulnerability; but in so doing she also underscores the vulnerability of us all. Marilyn McKenna is “any one of us”: her story could be our story, and her silence our silence.

Not here

Not in this wall of words,

considered deliberations

of five judges, muffling

argument, convoluted phrases.Not in the pathologist’s report.

The facial injuries

the worst she’d ever seen.

Multiple comminuted fracturesGoogle it.

Shudder.

Look her up

find her smiling out of snaps

like any one of us, not sensing

we are mortal.

In ‘Fragment’, a short, three-line poem dedicated to the memory of Marilyn McKenna, Whittaker demonstrates that while the temporality of the legal judgment may be delimited, the human impact of the facts that gave rise to it often lingers for generations to follow, and is rarely attenuated in any substantial or lasting way by the outcome of a court’s decision.

Fragment

i.m. MM

Someone, somewhere

wakes with something to tell her

aches with her absence.

The pain of the absence of Marilyn McKenna was also captured in a choral meditation, composed and produced by Alison Burns for the SFJP. Burns translated some of the words of Whittaker’s ‘Fragment’ poem into Latin, and used this as the basis for a commemorative ‘hymn’, entitled ‘Absentia’. ‘Absentia’ offers a poignant testament to the grief and loss that is masked within the legal text of the judgment. This score was subsequently performed by the University of Edinburgh choir at the School of Law’s LLB graduation ceremony in summer 2019. It was also performed at the Medical School graduation in 2019 at which Sophia Jex-Blake and her fellow female students – whose unsuccessful legal challenge in 1873 against the University’s refusal to allow them to graduate was also reimagined in the SFJP, sparking, as discussed below, inspiration for other SFJP artists – were posthumously awarded degrees.(62)

Though, as we reflect on in section four, the artistic and academic strands of the SFJP were not always as synergistic as they might have been, the dialogue between contributors in relation to Drury was rewarded and reflected in the fourth of Whittaker’s poems, which was inspired by feminist judge McDiarmid. During an early judgment writing workshop, McDiarmid spoke about how she ought to deal in her judgment with the influence of ‘institutional writers’ who, though long dead and ubiquitously white and male, held an ongoing and sizeable authority over Scottish criminal law principles. Inspired by a sense of the absurdity but also weight of such doctrinal constraint, Whittaker responded with this poem:

The institutional writers

Leather bindings cloak

ancient texts, fading robes

no longer fashionable,

donned nonetheless

to warm old bones.If we cast them aside

what will we do

bury them, burn them?

They no longer suit us

can’t just be thrown away.

Towards the end of the project, after having navigated and crafted her reimagined judgment, McDiarmid was also prompted to write to Whittaker to thank her for capturing in the series of poems that she had created about Drury “the essence of a number of issues which the hundreds of words used in the original judgment, and in mine, almost lose”. Similarly, Juliette Casey, an advocate who wrote the Drury commentary for the edited collection, also reached out to Whittaker to express how, for her, the poems underscored how “it is all too easy to get caught up in the very often arid legal detail and to lose sight of the human dimension”.(63)

The ways in which such creative work in the SFJP served to reconnect people “with the messiness of life” and expose “the singularity of pain and suffering which is mostly silenced and subsumed by all-too-general categories of law”(64) was also repeatedly remarked upon by those who visited our exhibitions. Attendees from within and outwith the legal community commented on how the art was “quite visceral – not dry like the law”, “really arresting”, “moving”, “powerful and humanising” and “allowed me to appreciate the human cost of legal decisions”.(65) A salient example of this came from a senior commercial law practitioner who, having been introduced to the substance of the project via a LinkedIn post about an SFJP event at the Faculty of Advocates, visited the digital exhibition, and remarked: “Powerful poetry, music and art. Someone said that creativity is just as important as literacy. How true.”

In respect of the poetry specifically, attendees at events often spoke of its “power” and “impact” and reflected on the fact that “the contrast between legal concepts and the description of violence is very effective” and “shocking”. Students who engaged with the artwork – some of whom embarked on producing their own found poems from selected judgments during our series of SJFP ‘bike tour’ workshops – also commented that while they had “never thought of law in the form of art until today”, the artwork was “really powerful”, “brilliant” and “a fantastic way to express personal opinions towards the judgment”.

Some of the artists also referenced and celebrated the opportunity afforded by the SFJP to curate legal narratives and consequences in alternative registers. Sofia Nakou worked with Becky O’Brien to produce a piece of theatre, depicted below, that was inspired by the struggle of Sophia Jex-Blake and her female colleagues to graduate from Edinburgh University Medical School, which culminated in an 1873 Court of Session case re-written in the SFJP by Chloë Kennedy.(66) In a context in which Edinburgh famously has more statues of animals than women and in which a recent campaign to commemorate Sophia Jex-Blake had been unsuccessful, Nakou and O’Brien wanted to respond to the absence on the streets of the nation’s capital of public monuments marking the struggles and contributions of women, and to express the “feelings and frustrations” provoked by those experiences of marginalisation.

Resonating with the ambition at the heart of all FJPs – that is, to resist women’s erasure from public spaces and the marginalisation of their perspectives from sites of decision-making – Jo Spiller produced a series of photographic images, three of which were portraits of the SFJP academic coordinators. These images both subverted the conventions of, and sought to offer an antidote to, the traditional white male portraiture that adorns the walls of court buildings, universities and other sites of power and knowledge across the country. Spiller noted that, for her, in being involved in the SFJP “the most rewarding thing… was the narrative connections that were made to lived experience, and being part of a collective process of humanising and giving voice to the individuals within the legal cases”.(67)

Jo Spiller, ‘A Fair Field and No Favour’

Through the medium of textiles, Kennedy-McNeill produced a series of three sculptures for the project, each of which was designed in different ways to bring home the affective and perspectival components – for parties and adjudicators alike – of the lived experience of legal judgments. One of these was a confessional space, produced as a response to the death by suicide of one of the parties in Salvesen v Riddell,(68) a case that was rewritten in the SFJP by Aileen McHarg and Donald Nicholson.(69) Though not on first glance the most obvious legal territory for feminist re-imagining, Salvesen v Riddell involved a family who had farmed land in the Highlands for generations and who had their connection to it severed by a landowner seeking to exercise his legal entitlement to sell the property. As such, it raised uncomfortable questions about community, connection, heritage, identity, autonomy and property, whilst also providing a newly emergent testing ground for the reach of Scottish devolutionary power. For Kennedy-McNeill, what was most important was to provoke an occasion for reflection and recompense in respect of the human costs of the landowner’s entitlements. She reflected on how it mattered that, in creating and showcasing this particular piece of work, “some people… got a rude awakening by the visceral rawness of the artistic response. A dialogue opened up that otherwise wouldn’t have, in spaces where conversations of that kind would never otherwise have taken place”. The success of Kennedy-McNeill’s work in achieving this effect was itself directly remarked upon by art critic Keira Brown, who described the textile art as “outstanding… interactive and literal thought-provoking pieces”.(70)

Jill Kennedy-McNeill, ‘For the Relics’ (photographer Julia Bauer)

This opening up of dialogue speaks, of course, to another of our objectives, which involved stimulating different communities of understanding in relation to law, gender and reform.

ii. Perspective, change and the significance of legal aesthetics

One of the central aims of the SFJP was to make the legal decisions that featured in our project, and the law that underpinned them, more accessible to a wider range of audiences. This was an end in itself, but also essential to our ambition of encouraging new critical perspectives on legal doctrine and its effects. We hoped these new perspectives might, in turn, foster alternative communities of understanding and stimulate new ways of imagining the law’s future, both with respect to the areas of law examined by our feminist judges and more generally. It was clear from the feedback we received from those members of the public that engaged with the creative strand of the SFJP that it significantly advanced our first aim – of increasing law’s accessibility. Attendees at our public exhibitions commented that the art “made the concepts more readily accessible” and took pleasure from seeing “artistic talent take on some seriously intimidating, technical, expert, and hierarchical subject matter”. These feelings were shared by some members of the legal profession too, such as one lawyer who remarked: “it is great to see the accessibility extended to the wider community!”.

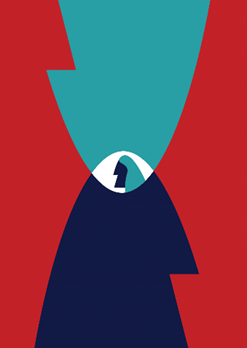

We found that this increased accessibility also allowed for greater awareness of the way that particular perspectives are always already manifest in the law and inevitably affect how law operates in practice. Making this clear to viewers helped to highlight the partiality that legal judgment unavoidably involves and to dispel the preconception that to employ a feminist (or any other) perspective when deciding cases would somehow be illegitimate.(71) One exhibition visitor commented, for example, that the art “helped me appreciate the extent to which perspective plays a role in the outcome of trials” and that it was “a really effective way of encouraging different perspectives”. This theme of the inevitable role of perspective in legal adjudication, and the importance but also contingency of exactly whose perspective dominates, is captured and conveyed by Kennedy-McNeill’s ‘Crime, Victimisation, Violence’.

Using the technique of anamorphosis, Kennedy-McNeill’s work can be interpreted as powerfully depicting what Pierre Schlag has called the “perspectivist” aesthetic of feminist and critical race legal scholarship. According to Schlag, from within the perspectivist aesthetic of law “the identities of law and laws mutate in relation to point of view. As the frame, context, perspective, or position of the actor or observer shifts, both fact and law come to have different identities”.(72) Adopting the perspectivist aesthetic therefore undermines the purported neutrality of the two processes most central to legal adjudication – of deciding factual relevance and applying the law. Both of these tasks are revealed to be highly dependent on the positionality of the judge. This, of course, means that the identity of the judge becomes crucial and it is impossible to claim that she is merely a vessel for the law. Instead, she must acknowledge the partiality she brings to applying the law, and the result is that her inevitably-situated self becomes a site of proactive, reflexive work.(73)

Jill Kennedy-McNeill, ‘Crime, Victimisation, Violence’ (photographer Julia Bauer)

This feature of the perspectivist aesthetic can also be observed in Kennedy-McNeill’s decision to depict Lady Justice not in her idealised form, Iusticia, but as the artist herself – an ordinary woman with a backstory, history and the capacity to acknowledge and even reorient the perspective(s) she brings to bear on law. Indeed, these facets of Kennedy-McNeill’s piece were specifically noted with critical approval, provoking the observation that the sculpture “metaphorically considers, reveals and conveys this notion of looking deep down at oneself to understand the victim, as we witness a blindfolded artist with a nod to Lady Justice, looking back at us in the mirrored sphere”.(74)

Of course, in contrast to art, which can more transparently accommodate plurality and contradiction, law demands decisiveness. (75) It is simply not possible for a judge to recognise that there are many different perspectives, each of which might generate different outcomes, and conclude that they are all equally valid. This is why, in our opinion, feminist judgments projects must, and do, embrace legal aesthetics beyond the perspectival. In particular, they can be described as embracing what Schlag has termed the “grid” and “energy” aesthetics.

The grid aesthetic, which pictures law as a “two-dimensional area divided into contiguous, well-bounded legal spaces”(76) is evident within traditional legal scholarship and adjudication that relies upon neat doctrinal categories and distinctions. Although feminist judgments projects seek to push the boundaries of traditional adjudication, as noted above, the feminist judge is bound by the same legal authorities and conventions that constrained the original judge. These constraints provide one ‘anchor’ that works to keep the feminist judge’s deliberations oriented. Since the feminist judge adheres to many of the law’s accepted classifications, she does not face a limitless range of equally-valid conclusions. But at the same time, adopting the energy aesthetic, which characterises reform-oriented conceptions of legal practice and recognises the power that judges have to shape and develop the law, she is provided with a further, and equally important, ‘anchor’. From within the energy aesthetic, “judicial opinion is no longer merely a set of legal propositions… but a legal force in the social world”(77) and, by virtue of her feminist commitments, the feminist judge has both an impetus for change and a direction in which to expend her energies.

These two ‘anchors’ provided by the grid and energy aesthetics mean that the feminist judge can avoid succumbing to pathologised extremes of any of the aesthetics she draws upon. In isolation, the perspectivist aesthetic can result in paralysis – if all perspectives are valid it is impossible to decide which should be prioritised when the time inevitably comes to reach a decision. Yet the grid aesthetic, as FJPs show so well, tends to be overly formalist and the pernicious myths of neutrality and objectivity too often remain unchecked within it. Finally, although the energy aesthetic is crucial to any ambition of aligning law more closely with social justice, it can lead to the illusion of change even where there is none. As Schlag puts it, “for those taken with the energy aesthetic, it is easy to believe that simply by enacting their aesthetic, by endorsing progress and transformative change, they are ipso facto contributing to this progress and change”.(78) Complacency in respect of reform achieved can be equally, if not more, of a hindrance to feminist ambitions than formal insistences on legal neutrality.

It is therefore only by combining these three legal aesthetics – grid, energy and perspectival – that the feminist judge becomes an effective and empowered agent for change. One viewer of the SFJP art captured this insight well, remarking that the works made her think about feminism as “something to be doing, creating, not just using or contemplating”. In a similar vein, another observed that the exhibition showed them “how structural inequalities permeate legal practise [sic], and require action from every level for widespread change”. Some of those who engaged with the artwork even offered suggestions as to what sorts of actions might effect change, including making the SFJP and the lessons it imparts “the basis of many future training sessions for professionals” and part of the “mandatory curriculum”.

Of course, the creative works produced by artists within the SFJP also clearly embodied their own energy aesthetic, particularly the performance of ‘To Sophia Jex-Blake’ by Nakou and O’Brien. An homage to an important but under-recognised pioneer of women’s education and medical practice, the piece shows a woman disturbing the scholarly calm of the classroom by throwing chairs around a university teaching space to create a makeshift plinth on which she is eventually commemorated. As one viewer commented, they found “parts of the filmed performance effective in conveying constructive rage at the institution”.

Sofia Nakou and Becky O’Brien, ‘To Sophia Jex-Blake’ (photographer Julia Bauer)

Something like this constructive rage was also evident in some of the ‘found poems’ created by students during the final task of our SFJP ‘bike tour’ workshops. Though we did not articulate it in these terms to participants, the overarching framework of these workshops mapped broadly onto Schlag’s three aesthetics. After a brief introduction to the aims and methods of feminist judging, students were asked to work closely on an allocated case, first to identify marginalised voices or seemingly neutral arguments that were ripe for feminist analysis, and then to sketch out a roadmap of what a feminist judgment might look like. We then asked the students to take a paragraph of, or argument within, the judgment and rewrite it through a feminist lens, channelling their own judicial voice in the process. By asking the students to pay due attention to the legal conventions and prior authorities, we were challenging them to work within, and push the boundaries of, the grid aesthetic. In the final session, we then encouraged them to experiment with alternative registers of engagement. Led by one of our artistic collaborators,(79) the students produced found poems, located images that depicted their responses to a given case, or sketched a plan for a piece of creative writing, drawing on the narratives and perspectives of one party to proceedings.

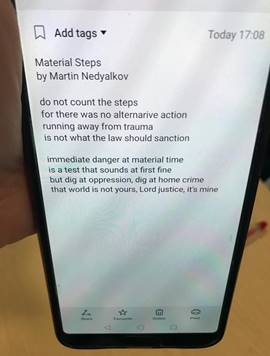

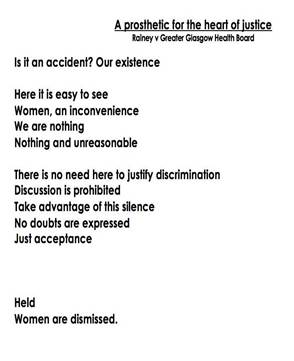

Many of the students’ creative responses embodied Schlag’s energy aesthetic by explicitly acknowledging the pressing need for legal – and social – change and naming the role of the judge in maintaining the status quo. The following two poems – ‘Material Steps’ and ‘A Prosthetic for the Heart of Justice’ – were written by Martin Nedyalkov and Alison Howells in response to the cases of Ruxton v Lang(80) and Rainey v Greater Glasgow Health Board(81) (re-imagined in the SFJP by Sharon Cowan and Vanessa Munro, and Nicole Busby respectively).(82) Each highlights a tangible frustration with judicial blindness to marginalised perspectives and starkly exposes what the authors perceived to be the source(s) of the injustice in each case.

Martin Nedyalkov, ‘Material Steps’ Alison Howells, ‘A prosthetic for the heart of justice’

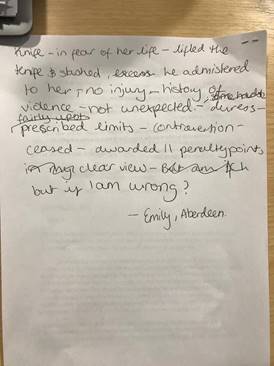

An acknowledgment of the perspectivist aesthetic and its dangers is on display, too, in the final line of this untitled poem by Emily (Aberdeen), written in response to the decision in Ruxton v Lang. In this case, a female accused, who had driven under the influence of alcohol to escape an abusive ex-partner who was threatening her with a knife, was denied the opportunity to put a defence of necessity to the jury. Turning the original judge’s assertion into a query with a sleight of punctuation, Emily writes: ‘clear view – but if I am wrong?’

Irrespective of whether they produced a creative work that they considered complete during this inevitably truncated component of the half-day workshops, students who participated were overwhelmingly enthusiastic about this process of bringing art and law together, and the transformative potential of the results. Almost all the students reported that they either strongly agreed (75%, n=70/93) or agreed (21%, n=19/93) that the artistic methods had helped them think differently about the legal issues involved, and the process of feminist judging (only one disagreed).(83) As one student put it: the “creative session [of the workshop] was really powerful – a very valuable way of thinking about alternative tools to effect change”.(84)

4. Challenges: knowledge, power and ethics

Notwithstanding the constructive insights and points of critical contestation provoked by the artistic strand of the SFJP, it would be misleading to present this as a seamless interdisciplinary collaboration from start to finish. In this section, we want to reflect on some of the tensions and challenges that we experienced, as well as some things that – with hindsight – we would have done differently, in the hopes of offering insights for those who might seek to embed creative perspectives in similar ways in other legal projects in the future.

i. Interdisciplinarity, power and knowledge differentials

It is ironic perhaps that in a project that set out to increase awareness of the importance of one’s own perspective and to encourage a critical reflection on the perspectives of others, one of the most substantial difficulties that we encountered in navigating collaborations across academic and artistic strands of the SFJP was the exclusionary nature of legal terminology and our tendency as academic co-ordinators to presume an engagement ‘on our turf’. This became less acute as the project progressed, as barriers broke down and shared discourses began to emerge that often focussed on the factual and human dimensions of legal cases. In the early stages of the project, however, it was clear that there was an atmosphere of ‘detached curiosity’ between academic and artistic collaborators, as each tended to cluster with like-minded allies and many queried how to bring contributions together effectively.

When asked to complete a short questionnaire about their experiences of being involved in the project, a number of the artists reflected on this: they spoke of legal language being “jargonistic”, “inaccessible”, “unapproachable” and “disengaging”, and of the concern for process and convention expressed by the academics who rewrote the judgments as at times “oppressive” and “constraining”. Some of the artists also spoke of how, especially in the early workshops, this cognitive disconnect had made them feel “isolated”, and that it took getting “in a room with the other artists” and “sharing how we felt about the project and what approaches we were thinking of taking” before “my worries went out the window”.

On the one hand, these experiences of bewilderment and isolation were productive for several of the artists, who reflected on the extent to which it gave them “real insight into how difficult it must be for ‘lay’ people” who seek to engage with the law as participants and subjects; and they used this in their artwork in different ways to enhance its accessibility. On the other hand, that we played a part in those early stages of the process in – albeit unwittingly – reinforcing what one creative contributor described in another context as “unhelpful and un-progressive hierarchies between academic and cultural practice” is a source of regret to us as coordinators. For this reason, we are even more grateful to all of those involved for working with us to navigate respectfully beyond such exclusionary logics.

In truth, of course, these experiences are also reflective of the reality that we were all effectively ‘learning on the job’ in respect of this aspect of the SFJP. Though, as noted, the template for feminist judgment projects across the globe is now in many respects well-established, there was no template for incorporating creative contributions on the scale and manner in which we wanted to in the SFJP. When we embarked on that process as coordinators, it is fair to say we did not have as clear a plan as we might have had about how best to integrate perspectives and set a tone for cross-disciplinary discourses that would be self-consciously open, respectful and generous. This is not to suggest that academic contributors were unwelcoming to the artists – far from it – but there was an inevitable ‘in-group’ effect grounded in peer familiarity and shared points of reference, which we ought to have been more mindful of in setting up the collaborative space, particularly in its exploratory stages.

Feminists know intimately both the opportunities and challenges of collaboration. Feminism is a large house with many rooms, but that does not mean that its inhabitants are always happy living side by side. Working together across disciplines, as well as across a range of feminist perspectives and media, was not a seamless process, either in terms of producing the work together and on time or in being able to have confidence that we listened to and heard each other fully along the way. Law is a very powerful discipline, one that can overwhelm other disciplinary practices and frameworks. Indeed, one of the feedback responses from a public exhibition of the artwork suggested that “law gave art a purpose” – a view that was not well received by many of our artists. We hope that we did not reproduce this sort of hierarchical or instrumentalising view of the art in the SFJP, but rather that we were able to produce what Joan Kee has called “a coalition of imaginations”.(85) However, we are aware of the dangers of rewriting our own history – one of an idyllic, interdisciplinary, collaborative journey that belies the unevenness of engagement and the limited opportunities for changing the terms of reference for the project laid out by the academics at the outset. Even at the end of the project, for example, one of our feminist judges remarked that the artistic works had primarily been “great for publicity”. This calls to mind the tension that inheres in attempts to make art serve a practical function: its ‘usefulness’ is confirmed but its subversive force is tamed. Instead of provoking rage or dissent, it becomes mere public relations,(86) or, in our case, the pretty, glossy part of the text-heavy edited collection.

More broadly, it is fair to say that there was a sliding scale in terms of how enthusiastically our ambitions to centre artistic perspectives, and the artwork produced in that process, were received by the judgment writers themselves. Not all legal academics involved in the project embraced the value and power of the artistic contributions to the same degree. At the same time, it was clear – as noted above – that some SFJP judges identified a power associated with the artwork that complemented, amplified and transcended their own rewritten judgments.

The artistic methods brought to the fore in the project also had a profound impact for some. For example, Jane Mair, who rewrote Coyle v Coyle,(87) a case regarding financial provision on divorce, within the project was clearly affected by the theatre workshop that we held in the early days of the SFJP. As noted earlier, this was designed – amongst other things – to ask our collaborators to experience and explore the embodied feeling of what it might mean to be a feminist judge. Speaking about this later in her reflective statement within the SFJP edited collection, Mair “wondered how I might use these ideas or sensations when I finally sat down to write my feminist judgment”. She found that the experience of this “silent, physical engagement”, which required her to insert her own body into a pose already adopted by a fellow-participant, came back to her when she tried to reconcile herself to the uncomfortable task of overturning “the authoritative words of a judgment and the real story of a couple’s lives”. Even more powerful, for Mair, was the “unfamiliar feeling of exposure” that she experienced during the workshop, which was one that led her to empathise deeply with real judges and to “offer [her] feminist judgment…not in criticism but in solidarity”.(88)

Allied to the specific ways in which knowledge differentials played out across the project is a broader question about ethical engagement across disciplines; and in the next section, we briefly reflect on some of the more pragmatic dimensions and challenges of that process.

ii. Creating art ethically

In setting up and pursuing this collaboration, we were required to make a number of practical and ethical decisions, several of which were not straightforward – for example, how to recruit and pay the artists, what level of remuneration would be fair, what we could hope artists would produce, and how to facilitate their attendance at workshops and other events. We also had to work out how we would do justice to the works when they had been produced and were ready for display. In truth, we arrived at answers to many of these questions in a relatively ad hoc way. At the time of the project’s inception, we did not anticipate that the artistic strand of the project would generate such significant, almost free-standing, interest.

Had we done so, we would likely have made changes to our commissioning processes. Greater transparency in recruitment would have been beneficial in any case and, with hindsight, it would have been preferable to have issued a call for proposals and sought the assistance of arts-based colleagues in sifting these. Instead, we called on artists we knew and relied upon ‘snowball sampling’ to bring others on board – a methodology that social scientists know to be somewhat problematic in its tendency to produce a sample that replicates the characteristic of those doing the sampling. We have reflected elsewhere on the difficulties we had in recruiting judges and commentators from diverse backgrounds, since both legal academia and the legal profession in Scotland are predominantly middle class, white, cisgender and able-bodied communities.(89) Although the project embraced an intersectional feminist approach, a more open recruitment process for artists may have helped to make the SFJP a more inclusive and diverse collective. Indeed, a more specific focus on how art could engage with and highlight the complex intersections of class, race, ethnicity, physical ability and nationality across the Scottish legal landscape would have enriched the project in ways that also enhanced its reach and impact. These are insights borne of hindsight, but they have forced us to reflect on what we would do differently in future collaborations of this kind.

Furthermore, while we were fortunate that one of our artistic contributors – Kennedy-McNeill – could take on the role of creative co-ordinator, the fact that she is based in London brought geographical and logistical challenges. Finally, although we were able to secure funding to pay each artist commission and consultancy fees, that funding was ad hoc and fragmented, requiring us to stitch together resources in ways that demanded an extra layer of creativity. This speaks to the (un)availability of dedicated funding for these kinds of large scale, critical, interdisciplinary projects. We arrived at payment figures and contractual and licensing agreements through a rather labour-intensive but informal process of asking colleagues and collaborators for advice. It is heartening that one of our institutions, the University of Edinburgh, has now produced guidelines that outline specific recruitment processes; commission requirements, such as artist briefs, selection panels, diversity protocols and curatorial support; as well as timelines and budgets for creative productions. Unfortunately, these were not available to us when we needed them.

The artistic works that were produced themselves also raised further ethical issues, due to the subject matter of the source materials. Each of the cases re-imagined for the SFJP is reported in the public domain, and all the material relied on by the artists is publicly available. This meant that none of the breaches of privacy or trust that have complicated other creative enterprises arose.(90) Nevertheless, sensitive issues and real people feature in the cases and these are reflected in the artworks, so ensuring that they depicted these people and their experiences in a responsible way was a high priority for all SFJP artists. The technique our artists often adopted was one of abstraction, but abstraction of a very different kind than legal adjudication typically involves. Rather than marginalising the complex, personal human dimensions of the case in the pursuit of ‘relevance’ or neutrality, the artists’ abstractions were instead aimed at keeping these humanising details in view whilst simultaneously avoiding voyeurism and appropriation.

Whittaker, for example, was clear that in responding through poetry to Marilyn McKenna’s murder by an abusive ex-partner, she “couldn’t appropriate her [McKenna’s] voice”, adding “nor did I want to. It’s not my story to tell.” Instead, she explained to us that she focused on her own “reactions to the feminist judge’s report… and to the original judgment”. Likewise, Nakou explained that the piece she created with Becky O’Brien “told the story of Sophia Jex-Blake in a particularly abstract way” which, she felt, was a “safer” way to approach a real person’s narrative. Instead of concentrating on Jex-Blake as a person, Nakou and O’Brien concentrated on the frustration they felt when encountering her story. Kennedy-McNeill said she was “*acutely* conscious” of the likelihood that the family of the farmer at the centre of the Riddell case would still be alive. She spent time discussing her vision for the piece with a close friend whose mother had died by suicide before embarking on the work and ultimately felt the only way she would be “able to attempt to depict a life and a legacy that I had no right to portray” was to “abstract the subject matter and make it an inclusive, immersive experience that encouraged the viewer/participant to think about their own feelings”.

Jess Orr, who produced the short story ‘A Woman’s Anatomy’ in response to the Sophia Jex-Blake case, was more unusual in this respect amongst the SFJP artists since she consciously assumed the voice of her key protagonist within her creative work. For Orr, however, the distance ensured by the passage of time provided important reassurance. She told us that by producing a “creative reinterpretation of a historical figure, I didn’t really encounter any ethical issues aside from the personal aim to represent Sophia as reflectively and respectfully as I could”. She achieved this in her short story through a sensitive but powerful imagining of the everyday experiences of Jex-Blake as she struggled to access the university classrooms, as well as the turmoil of the court case and animosity that preceded it. Juxtaposing this alongside extracts from medical texts of the time, which were often stark and dehumanising, including in their expositions of the female anatomy as an aberration from the male norm, Orr generated a striking narrative contrast that heightened sympathy for the women’s plight.

Encouraging audiences to reflect empathetically and critically on law and its impacts was, of course, an important part of what we wanted to achieve with the project and, as discussed above, for us and many of the contributors, the art was an important component in realising this ambition. This supports what others have said about artists and their creative outputs, which is that they “offer others not only opportunities for heightened sensibility, expression, communication or imaginative representation, but unique occasions for exposure, discovery and an intensified awareness of the world”.(91) This was the role we hoped the art would play in our pedagogical efforts too, taking the view that “good art is more about the shaping of consciousness and the formation of perception rather than didactic prescription”. (92)

This experience of exposure is double-edged, though, and can result in feelings of shock, distress and disillusionment, as well as resolve, inspiration and hope. In our exhibitions and talks we tried to respond to this concern by issuing content warnings and seeking to leave audiences feeling empowered and committed to improving the law. Indeed, these dual ambitions – of critical reflection and cautious optimism – find vivid expression in the illustrations produced within the SFJP by Rachel Donaldson. Entitled ‘Look Back, Look Forward’, her series aims to capture the balance that might be achieved by taking previous cases of injustice seriously, and the value in looking back at such cases to inform future engagement with the law. They were described by one reviewer as “a bold series of graphic works which cleverly encompass the spirit of the Feminist Judgments Project as a whole”.(93)

Rachel Donaldson, ‘Look Back, Look Forward’

It was clear that some of those who attended SFJP exhibitions, or participated in the Law School tour, were affected by the artwork. Though we did not require any of the students who created their own poems to share them with us, several of them chose to do so in the workshops and found this an emotional experience. We recollect one student in particular who was keen to continue to read her poem but did so through tears. This student, and others like her, reported that they found the workshops and the creative engagement very positive, notwithstanding – or perhaps because of – its emotional impact. In that sense, the process of looking back in order to look forward was also part of an individual and highly personal journey for some participants. Reassuringly, in light of these ethical concerns, the feedback we received from students who attended our ‘bike tour’ workshops suggests they left feeling awakened and energised. One wrote that they found the experience “incredibly eye opening”, another vowed they would “remember to keep questioning everything!!” and another reported that they felt “empowered to continue [their] studies”. These responses indicated that the passion and insights that all of our collaborators – academic, activist and artistic(94) – generated through this project, have the potential to bring home to a range of audiences how legal notions of neutrality and objectivity can be exposed and eviscerated, and the importance of perspective and “ethical imagination”(95) in achieving social justice.

5. Conclusion

When prompted to reflect on the importance of the artistic strand of the project, our creative co-ordinator Jill Kennedy-McNeill referenced a passage from Oppenheim’s Bread and Roses:

As we come marching, marching, un-numbered women dead

Go crying through our singing their ancient call for bread,

Small art and love and beauty their trudging spirits knew

Yes, it is bread we fight for, but we fight for roses, too.(96)

This poem, made famous by the Bread and Roses strike of 1912, is a vital reminder that when we seek justice, as we often do through law, we are seeking something deeper and more elusive than just the satisfaction of our material needs. The women who mobilised these words in their fight for fair pay were demanding more than an end to their physical hunger; they were demanding dignity and respect, and the capacity for human flourishing too. They were communicating something that we, and anyone who cares about trying to make law more just, should bear in mind: that when law fails to hear the lessons offered from ‘outside’, for example through art, it may well miss something that is central to the human experience.

In this article, we have presented our attempts to honour these ambitions. Through honest reflection on our methodological and ethical choices and by sharing the testimonies of those who have interacted with the art, as well as the artists themselves, we have argued that art and law are not as distinct as one might think. Furthermore, we have shown that paying attention to discourses and practices from ‘outside’ law can open the law and its impacts up to different kinds of scrutiny and can facilitate forms of critical engagement that would not otherwise be possible. Through the co-production of rewritten feminist judgments, artistic work and pedagogical techniques, the SFJP is an example of the different sorts of legal aesthetics that can emerge in critical, interdisciplinary, collaborative endeavours. The process of collaboration was not a seamless one, however, and there is always a risk that this kind of work remains somewhat compartmentalised and additive rather than properly interwoven and synergistic. It is also true that – despite the leverage that can come from the use of artistic methods – legal knowledge is often stubbornly unreceptive to external critique, remaining for many of those who study and practise it a closed system of text-based rules. In trying to evidence the real and significant social impact of this sort of work, we risk what might be called co-option by institutional and sector-wide forces whose agendas are not coterminous with our own. Nonetheless, while we remain cognisant of these pitfalls, we believe that the SFJP and projects like it have the potential to enable moments of deep engagement and connection that reach beyond the courtroom and render vivid the impact of legal decisions, creating richer and more democratic communities of understanding.

* Sharon Cowan is Professor of Feminist and Queer Legal Studies at the University of Edinburgh, email: s.cowan@ed.ac.uk. Chloë Kennedy is Senior Lecturer in Criminal Law at the University of Edinburgh, email: chloe.kennedy@ed.ac.uk. Vanessa E. Munro is Professor of Law at the University of Warwick, email: V.Munro@warwick.ac.uk. The authors are indebted, first and foremost, to all the artistic and academic contributors to the Scottish Feminist Judgments Project, and in particular to Jill Kennedy-McNeill who acted as Coordinator of the SFJP artistic strand. We are grateful to the Clark Foundation, Royal Society of Edinburgh and ESRC, as well as the Universities of Edinburgh and Warwick, for funding various aspects of SFJP activities, including artistic exhibitions. We would also like to thank all those who have attended the SFJP exhibitions (real or virtual), and in particular the students whose own creative outputs are featured – with permission – in this piece. Finally, we are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on an earlier version.

(1) Sonia Sotomayor, 'A Latina Judge’s Voice' (2015) 13 Berkeley La Raza Law Journal 87, p 91.

(2) See, in particular, Diana Majury, ‘Introducing the Women’s Court of Canada’ (2006) 18(1) Canadian Journal of Women and the Law 1; Rosemary Hunter, Clare McGlynn and Erika Rackley (eds), Feminist Judgments: From Theory to Practice (Oxford, Hart Publishing, 2010); Heather Douglas, Francesca Bartlett, Trish Luker and Rosemary Hunter (eds), Australian Feminist Judgments: Righting and Rewriting Law (Oxford, Hart Publishing, 2014); Elisabeth McDonald, Rhonda Powell, Māmari Stephens and Rosemary Hunter (eds), Feminist Judgments of Aotearoa New Zealand: Te Rino: A Two-Stranded Rope (Oxford, Hart Publishing, 2017); Máiréad Enright, Julie McCandless and Aoife O’Donoghue, Northern/Irish Feminist Judgments: Judges’ Troubles and the Gendered Politics of Identity (Oxford, Hart Publishing, 2017); and Kathryn Stanchi, Linda Berger and Bridget Crawford (eds), Feminist Judgments: Rewritten Opinions of the United States Supreme Court (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2016).

(3) Sharon Cowan, Chloë Kennedy and Vanessa Munro (eds), Scottish Feminist Judgments: (Re)Creating Law From the Outside In (Oxford, Hart Publishing, 2019).

(4) E.g. Troy Lavers and Loveday Hodson (eds), Feminist Judgments in International Law (Oxford, Hard Publishing, 2019), who formed judgment writing “chambers”, and sometimes included a dissenting judgment.

(5) Douglas et al (n2), who included a 1934 judgment, rewritten by a 2035 court.

(6) McDonald et al (n 2), who included mana wahine judgments, based on Maori values.

(7) See Enright et al (n 2).

(8) African, Indian and Scottish Feminist Judgments Projects, ‘Feminist Judgments at the Intersection’ (2020) Feminist Legal Studies, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10691-020-09428-0

(9) Enright et al (n 2) p v-vi, 4.

(13) See Christine Neejer, ‘Cycling and Women’s Rights in the Suffrage Press’ (PhD Thesis, University of Louisville, 2011), available at https://ir.library.louisville.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2046&context=etd. See also Louise Dawson, ‘How the Bicycle Became a Symbol of Women’s Emancipation’, The Guardian (4 November 2011) https://www.theguardian.com/environment/bike-blog/2011/nov/04/bicycle-symbol-womens-emancipation

(14) The ‘Law School Bike Tour’ assisted in capturing the attention and goodwill of many supporters, creating an embodied, performative contribution in and of itself, and enabling us to raise a substantially higher amount of funds for our chosen charities than we would have anticipated (over £5,000): https://www.scottishlegal.com/article/feminist-legal-academics-deliver-six-workshops-across-scotland-in-200km-cycle-tour

(15) Sharon Cowan, Chloë Kennedy and Vanessa Munro, ‘The Scottish Feminist Judgments Project on Tour: (Re)Teaching and (Re)Learning Law’, Canadian Legal Education Annual Review (forthcoming, 2020). The workshops have subsequently been delivered to students from Warwick, Birmingham and Leeds Universities.

(16) Linda Mulcahy, ‘Eyes of the Law: A Visual Turn in Socio-Legal Studies?’ (2017) 44 Journal of Law and Society 111, p 118.

(17) See also: Andreas Philippopoulos-Mihalopoulos, ‘Atmospheres of Law: Senses, Affects, Lawscapes’ (2013) 7 Emotion, Space and Society 35; Lucy Finchett-Maddock, ‘Forming the Legal Avant-Garde: A Theory of Art/Law’ (2019) Law, Culture and the Humanities, online 13 September 2019: https://doi.org/10.1177/1743872119871832