Helen Xanthaki*

Emily Grabham’s paper offers an insightful analysis on the legislative aspect of a uniquely innovative and challenging research graced by theoretical connotations and practical applicability. My response derives from the narrow world of legislative drafting and comes with a disclaimer of complete and utter naiveté in the substantive aspects of the article and the wider research. Let me reassure you: this is not unusual in legislative drafting. A drafter’s awareness of the policy and law related to the drafting task is unnecessary. In fact, it is often unwelcome. The task of a drafter is to “speak” the regulatory messages to the legislative audiences in a manner that enables them to receive them as they were intended. Being unaware of the policy and law tinging the legislative communication that is legislative drafting (Stefanou, 2011, 2008) may offer the drafter the opportunity to place themselves in the position of the lay user, thus enabling them to identify with greater accuracy the elements of the communication needed to make the regulatory message accessible, and indeed accessible in its fullness.

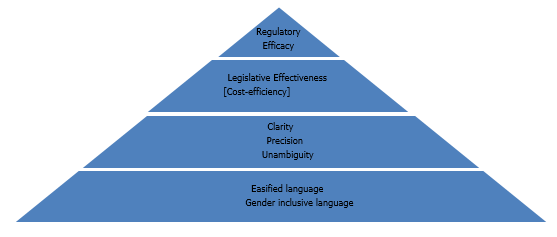

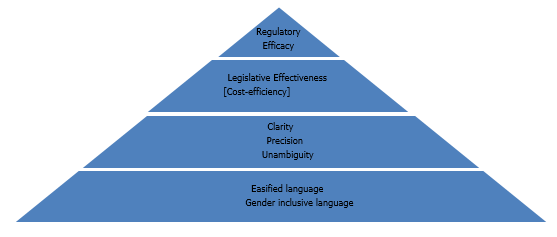

Within a functionalist realm, legislation is a tool for regulation or the legislative expression of government policy.(1) In other words, regulation is the process of putting government policies into effect (Alexander and Sherwin, 2001), to the degree and extent intended by government (see National Audit Office and Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, 2011). One of the many regulatory schemes (Miller, 1985; BRTF, 2005) or tools (see OECD, 2002a, para. 0.3; OECD, 2002b) available to governments (Flückiger, 2004) is formally authorised legislation (Blank, 2010). Legislation serves as one of the many media available to regulators. It is a regulatory solution of last resort (Weatherhill, 2007). In order to convey the regulatory message to legislative users, who are expected to alter their behaviour accordingly, legislation must use the language of lay users as a means of explaining clearly how their behaviour is expected to change and how law reform is to come about. Communicating these messages to the legislative audience as clearly as possible remains the best way in which the legislation can, with the synergy of the other actors of the policy process (Chamberlain, 1931), achieve the desired regulatory results (Mader, 2001). In that context, drafters strive to contribute to regulatory efficacy by producing an effective legislative text, as per the diagram below.(2)

Regulatory efficacy is the extent to which regulators actually achieve the desired regulatory results (see Xanthaki, 2008; Mousmouti, 2012). This is not a goal that can be achieved by the drafter alone (Chamberlain, 1931): legislation requires a solid policy, appropriate and realistic policy measures for its achievement, cost-efficient mechanisms of implementation, and ultimately user willingness to implement and judicial inclination to interpret according to legislative intent (see Hull, 2000; Karpen, 1996; Mader 1996).

The drafter’s limited contribution to efficacy is effectiveness,(3) defined as the extent to which the observable attitudes and behaviours of the target population correspond to the attitudes and behaviours prescribed by the legislator (Mader, 2001); or “the fact that law matters: it has effects on political, economic and social life outside the law – that is, apart from simply the elaboration of legal doctrine” (see Snyder, 1993, p. 19; Snyder, 1990); or a term encompassing implementation, enforcement, impact, and compliance (Teubner, 1992); or the degree to which the legislative measure has achieved a concrete goal without suffering from side effects (Müller and Uhlmann, 2013); or the extent to which the legislation influences in the desired manner the social phenomenon which it aims to address (Cranston, 1978; Iredell, 1981); or a consequence of the rule of law, which imposes a duty on the legislator to consider and respect the implementation and enforcement of legislation to be enacted (Voermans, 2009); or a measure of the causal relations between the law and its effects: and so an effective law is one that is respected or implemented, provided that the observable degree of respect can be attributed to the norm (Mousmouti, 2012). If one attempts to use all of the elements of these enlightened definitions of effectiveness, one could suggest that effectiveness of legislation is the ultimate measure of quality in legislation (Xanthaki, 2008), which reflects the extent to which the legislation manages to introduce adequate mechanisms capable of producing the desired regulatory results (see Office of the Leader of the House of Commons, 2008), para. 24. In its concrete, rather than abstract conceptual sense, effectiveness requires a legislative text that can (i) foresee the main projected outcomes and use them in the drafting and formulation process; (ii) state clearly its objectives and purpose; (iii) provide for necessary and appropriate means and enforcement measures; (iv) assess and evaluate real-life effectiveness in a consistent and timely manner.(4)

Legislation aims to communicate the regulatory message to its users as a means of imposing and inciting implementation. It attempts to detail clearly, precisely, and unambiguously what the new obligations or the new rights can be, in order to inform citizens with an inclination to comply how their behaviour or actions must change from the legislation’s entry into force. The receipt of the legislative message in the way that it was sent by the legislative text is crucial for legislative effectiveness and, ultimately, for regulatory efficacy.

Easified language, as a development of plain language, aims to introduce principles that convey the legislative/regulatory message in a manner that is clear and effective for its specific audiences. Easified language encompasses the analysis of the policy and the initial translation into legislation, the selection and prioritisation of the information that readers need to receive, the selection and design of the legislative solution, and choices of legislative expression. Easified language extends from policy to law to drafting. The blessing of this ambitious mandate comes with a curse of relativity. Easification requires simplification of the text for its specific audience, and thus requires an awareness of who the users of the texts will be, and what kind of sophistication they possess.

Recent empirical data offered by a revolutionary survey of the UK’s National Archives in cooperation with the Office of Parliamentary Counsel (OPC)(5) show that legislation is read by at least three categories of people: lay persons reading the legislation to make it work for them (Gracia, 1995; Pi and Schmolka, 2000; Schmolka, 1995), sophisticated non-lawyers using the law in the process of their professional activities, and lawyers and judges (see Bertlin, 2014, pp. 27-28). This is a real legislative revelation that has led to legislative revolution. Identifying the users of legislation has led to not one but two earthquakes. First, the law does not speak to lawyers alone. Second, the law does not speak to the ‘average man’.

The expression of gender in legislative studies remains in the periphery of plain language or, more recently, clarity debates.(6) Gender-neutral language (GNL) refers to language that includes all sexes and treats women and men equally (Greenberg, 2008a). Traditionally, in our society, men have been the dominant force and our language has developed in ways that reflect male dominance, sometimes to the total exclusion of women. Gender-neutral language, also called non-sexist, non-gender-specific, or inclusive language, attempts to redress the balance.(7) Admittedly, the mere reference to GND seems to bring many a drafter around the Commonwealth to covert amusement (Hill, 1992). It is often ridiculed as one more feminist invasion in legislative drafting, and it is often justified by reference to the provision common in many Interpretation Acts that foresee that ‘“he” includes “she”’.

Gender Inclusive Language (GIL) language takes the argument further. In an attempt to put into effect the principle that every citizen is equal before the eyes of the law, it aims to delete sex and gender from the expression of the subjects of legislation. Therefore, instead of ensuring that both men and women are within the scope of legislative expression, as is the case with GNL, GIL aims to eliminate the consideration of sex and gender altogether. As a result, it differs from GNL in that it avoids any classification of sex and gender. With GIL the subject does not need to be classified or to identify as any sex or gender.

A GI draft simply renders sex and gender irrelevant as a consideration. This is not an innovative approach. Legislators have achieved that goal with reference to race, for example.(8) “Legislation that is race-inclusive does not list categories of race and ethnicity.” In application of the same approach, GI legislation does not refer to “anyone, male or female or any other sex or gender”. In this respect, GIL can be open to opposition by some feminist groups, who may find that the elimination of considerations of sex and gender is counter-productive to the feminist cause that often aims to draw attention to existing differentiations against women. Of course, this would be incorrect. GIL may eliminate sex and gender from legislative expression but this does not affect pro-women policy choices, nor their expression in gender specific language where appropriate. In fact, one could argue that in the environment of a GIL statute book, gender specific language would have even more impact in drawing the users’ attention to the specific position of women in gender specific legislative texts.

In the English-speaking world, gender neutrality is gaining ground. GNL has been adopted by the New South Wales Office of Parliamentary Counsel in 1983, by New Zealand in 1985, by the Australian Office of Parliamentary Counsel in 1988, by the UN and the International Labour Organization roughly around 1989, by Canada in 1991, by South Africa in 1995, and by the US Congress, albeit not consistently, in 2001. In the UK GNL is applied to all government Bills and Acts since 2007.(9) However, most Commonwealth drafters in other jurisdictions find it difficult to understand the rationale of GND, since most Interpretation Acts expressly state that “he includes she”.(10)

The problem is that few non-lawyers are aware of the Interpretation Act. With reference to unambiguity (Statsky, 1984, p. 184), “he” can be both “he” and “she” in a great number of statutes, but equally “he” is only “he” where gender specific language is actually appropriate (Corbett, 1991, p. 21). For example, in jurisdictions where the military is exclusively male, one wonders whether the application of “he includes she” could lead to the admission of women in the army by broad interpretation of the male pronoun under the Interpretation Act, especially where there is no express provision to the contrary. Mary Jane Mossman, a Canadian legal academic explains the reasons for non-discriminatory language in law as being important to promote accuracy in legal speech and writing; to conform to requirements of professional responsibility; and to satisfy equality guarantees in laws and the constitution (Mossman, 1995). GND is also practicable (Petersson, 1999), provided that “it comes at no more than reasonable cost to brevity or intelligibility”.(11) In fact, there no technical reason why legislation should not be drafted in a way that avoids gender-specific pronouns (Greenberg, 2008b).

The identification of the most appropriate drafting technique for the expression of gender in legislation can be undertaken by means of Thornton’s methodology for legislative drafting. Let us begin with stage 1, understanding the proposal. The objective of gender neutrality used to be equality between male and female. Moving on to stage 2, analysing the proposal, leads us to the realisation that binary rigid approaches to sex and gender are no longer prevalent in society. Gender inclusivity is now perceived by the LGBTQI+ community to extend far beyond two sexes. The purpose of GIL is to remove gender as a characteristic of the legislative subject, as a means of putting into effect the fact that gender is not a relevant factor in the eyes of the law, unless of course sex and gender specificity is required. Moving on to stage 3, designing the legislative solution, one is led to identify a language structure that ignores gender considerations whilst serving clarity, precision, and unambiguity in its widest subject inclusiveness. Here lies the revelation: current language structures are bound to grammatical expression that is intrinsically linked to male/female/neutral (in some languages). And therefore, in moving to stage 4 and composition, the only solution available seems to be to depart from current language and introduce a new gender inclusive form of words. For stage 5, verification, one can add that a new GI expression serves the purpose of inclusivity both as an expression but also as a novelty that can attract attention to the new inclusivity ethos.

If generic legislative expression aims to pursue clarity by removing sex and gender from the relevant characteristics of the generic legislative user, then gender inclusivity seems to serve best. Thus, gender specific terms (such as “he”, “she” in all their forms) are to be used only when referring to just a male, or just a female person. Moreover, gender neutral terms (such as the prevalent in the US (Williams, 2008) “he and she”, “he/she”, or “s/he”) are to be used for binary expression only. In other words, there is a place for more than one technique, as there is a place for more than one regulatory goal related to gender. Where gender specificity is pursued, for example, for the introduction of affirmative action supporting women, then legislative expression can and must only be gender specific. This serves clarity of expression, which in turn informs clarity of the legislative communication, legislative effectiveness, and ultimately regulatory efficacy. Where gender neutrality is pursued, then gender neutral drafting techniques serve gender neutral regulatory goals. But in generic legislative communication, which requires gender inclusivity, it is the latter that serves best.

The preferred technique for real gender inclusivity is the use of the singular “they”. This technique was favoured by authors prior to the nineteenth century (Bodine, 1975; Petersson, 1998) and is still common in contemporary English (Swift and Miller, 1980, pp. 38–40). Whether this popular usage is correct or not is perhaps a matter of dispute. The OED (2nd ed, 1989) records the usage without comment. The Shorter OED (5th ed, 2002) notes that it is “considered erroneous by some”. It is certainly well precedented in respectable literature over several centuries.(12) However, in the debate on gender-neutral drafting in the House of Lords in 2013 a number of peers expressed concern about the use of “they” as a singular pronoun. This may explain why the technique lost support in the newer versions of the OPC’s Guidance from 2014 onwards (see OPC, 2014, pp. 29-30). However, the technique is supported by authors, as it is the most compatible with spoken English (Schweikart, 1990). An example of it can be found in the Counter-Terrorism Act 2008, section 61(1): “References in this Part to a person being dealt with for or in respect of an offence are to their being sentenced ... in respect of the offence.” And a further example comes from the Local Democracy, Economic Development and Construction Act 2009, Schedule 1, paragraph 2(5)(b): “… the chair holds office ... in accordance with the terms of their appointment.” The technique is rather innovative, since it uses a grammatical error to draw the reader’s attention to gender inclusivity. But at the same time it demonstrates quite rightly that drafters must use grammar without being its slave. It is better to be inelegant than uncertain (Aitken and Piesse, 1995, p. 57).

Gender inclusivity is a concept much wider than gender neutrality. Neutrality promotes equality between men and women and can therefore be viewed as an expression of feminism in legislative drafting. In contrast to that, gender inclusivity promotes the elimination of gender from the attributes of the subjects of legislation. It goes beyond gender equality and reflects the continuous evolution of the LGBTQI+ movement. From the point of view of substantive law, gender inclusive legislation expresses to a fuller extent the constitutional principle of equality in the eyes of the law: everyone, not just men and women, is equal before the eyes of the law. From the point of view of legislative drafting, gender inclusivity puts to effect to a fuller extent the requirement of clarity. In legislation where all citizens are subjects of the regulation, gender inclusivity conveys expressly and clearly the subjection of all citizens of any or no gender to the regulatory and legislative messages of legislation. Moreover, by contrast, gender inclusivity draws attention to gender specificity, where needed, as it contrasts loudly with the introduction of legislative texts addressed exclusively to specific genders.

In that respect, gender inclusivity enhances clarity in legislative expression, as it expresses with clarity, precision, and unambiguity if and where gender is relevant in legislation. As a tool to clarity (which encompasses precision and unambiguity as sine qua non), gender inclusivity enhances legislative effectiveness (Wilson, 2011; Xanthaki, 2008). It ensures that users understand fully whether the legislation addresses and covers them or not, thus rendering compliance an issue of subjective intention, not intelligibility of legislative communication. In turn, legislative effectiveness serves regulatory efficacy, in that it serves as a tool for the achievement of policy/regulatory results.

But GI is not the only regulatory goal pursued by all legislation. There is certainly still scope for GN policies, whose regulatory aim is to redress the balance of gender inequality in society (see UNDP, 2003, p. 21). Thus, the choice of the most effective GNL tool is to be made on the basis of two criteria: one, clear inclusion of the female; and two, education of the users on the changed policy. This calls for a tool that quickly identifies the new position whilst at the same time reflecting gender equality. On that basis, the singular plural technique is ideal: it breaks the barriers of an inherent gender specific language and uses a grammatically unconventional form to alert the user of the departure from gender specific to gender neutral. But, in doing so, it eliminates the female from legislative expression. In that respect binary legislative expression could serve where the regulatory message is addressed to an exclusively female and binary legislative audience: “she” brings to light the female but excludes not just the male but the non-binary also.

Similarly, there is still scope for gender specific regulatory goals. And it is there, and only there, that gender specificity can serve as the optimal expression of this policy choice.

To conclude therefore it is important to link the choice of legislative expression to the choice of gender regulation on an ad hoc basis. It is very important to state that “he” no longer includes any other than him and him alone. But “he” remains the optimal legislative expression if “he” is what is really meant. Thus, the choice of legislative expression within the de-regulation of gender in law project is far from a solitary one. Legislative expression is simply a statement of a policy choice. And here there are two: gender neutrality versus gender inclusivity. It remains therefore a choice of project direction that will inform its expression in the hypothetical draft law. Exciting times ahead!

Aitken, J., Piesse, E., 1995. The Elements of Drafting. The Law Book Company Limited, Sydney.

Alexander, L., Sherwin, E., 2001. The Rule of Rules: Morality, Rules and the Dilemmas of Law. Duke University Press, Durham NC.

Better Regulation Task Force (BRTF), 2005. Routes to Better Regulation: A Guide to Alternatives to Classic Regulation. https://www.eesc.europa.eu/resources/docs/routes_to_better_regulation.pdf

Bertlin, A., 2014. What Works Best for the Reader? A Study on Drafting and Presenting Legislation. The Loophole 2 (May), 25–49. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/326937/Loophole_-_2014-2__2014-05-09_-What_works_best_for_the_reader.pdf

Blank, Y., 2010. The Reenchantment of Law. Cornell Law Rev. 96, 633–670.

Bodine, A., 1975. Androcentrism in Prescriptive Grammar: Singular “They”, Sex-Indefinite “He”, and “He or She”. Lang. Soc. 4, 129–146.

Burchfield, R. W., 2004. Fowler’s Modern English Usage, 3rd ed. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Chamberlain, J., 1931. Legislative Drafting and Law Enforcement. Am. Labor Legis. Rev. 21, 235–243.

Commission of the European Communities, 2002. European Governance: Better Lawmaking. Communication from the Commission. COM 2002 275 final, 5 June. Brussels.

Corbett, G.G., 1991. Gender, Cambridge Textbooks in Linguistics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Cranston, R.F., 1978. Reform Through Legislation: The Dimension of Legislative Technique. Northwest. Univ. Law Rev. 73, 873–908.

Desprez-Bouanchaud, A., Dooalege, J., Ruprecht, L., 1999. Guidelines on Gender-Neutral Language. Unit for the Promotion of the Status of Women and Gender Equality, UNESCO.

Driedger, E.A., 1976. The Composition of Legislation: Legislative Forms and Precedents. Ministry of Justice, Ottawa.

Flückiger, A., 2004. Régulation, dérégulation, autorégulation : l'émergence des actes étatiques non obligatoires. Rev. Droit Suisse 2, 159–303.

Gracia, J., 1995. A Theory of Textuality: The Logic and Epistemology. SUNY Press, Albany.

Greenberg, D., 2008a. The Techniques of Gender Neutral Drafting, in S. Stefanou and H. Xanthaki, eds. Drafting Legislation: A Modern Approach. Ashgate, Aldershot, pp. 63–76.

Greenberg, D., 2008b. Craies on Legislation: A Practitioner’s Guide to the Nature, Process, Effect and Interpretation of Legislation. Sweet and Maxwell, London.

High Level Group on the Functioning of the Internal Market, 1992. The Internal Market After 1992: Meeting the Challenge. European Commission.

Hill, W.B., 1992. A Need For The Use Of Nonsexist Language In The Courts. Wash. Lee Law Rev. 49, 275–278.

Hull, D., 2000. Drafters Devils. The Loophole (June), 15–25. https://www.calc.ngo/sites/default/files/loophole/jun-2000.pdf

Iredell, J., 1981. Social Order and the Limits of Law. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Karpen, U., 1996. The Norm Enforcement Process, in U. Karpen and P. Delnoy, eds. Contributions to the Methodology of the Creation of Written Law. Nomos, Baden-Baden, pp. 51–62.

Mader, L., 2001. Evaluating the Effects: A Contribution to the Quality of Legislation. Statute Law Rev. 22, 119–131.

Mader, L., 1996. Legislative Procedure and the Quality of Written Law, in U. Karpen and P. Delnoy, eds. Contributions to the Methodology of Written Law. Nomos, Baden-Baden, pp. 62–74.

Miller, J., 1985. The FTC and Voluntary Standards: Maximizing the Net Benefits of Self-Regulation. Cato J. 897–903.

Mossman, M.J., 1995. Use of Non-Discriminatory Language in Law. Int. Leg. Pract. 20, 8–14.

Mousmouti, M., 2012. Operationalising Quality of Legislation through the Effectiveness Test. Legisprudence 6, 191–205.

Müller, G., Uhlmann, F., 2013. Elemente einer Rechtssetzungslehre. Asculthess, Zurich.

National Audit Office and Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, 2011. Delivering Regulatory Reform. Stationery Office. London. https://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/02/1011758.pdf

OECD, 2002a. Alternatives to Traditional Regulation. https://www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/42245468.pdf

OECD, 2002b. Regulatory Policies in OECD Countries: From Interventionism to Regulatory Governance. OECD, Paris. http://regulatoryreform.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/OECD-Regulatory-Policies-in-OECD-Countries-2002.pdf

Office of the Leader of the House of Commons, 2008. Post-legislative Scrutiny – The Government's Approach, Cm 7320. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/228516/7320.pdf

Office of the Parliamentary Counsel, 2014. Drafting Guidance. Archived at: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20141211024015/https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/drafting-bills-for-parliament

Office of the Parliamentary Counsel, 2011. Working with Parliamentary Counsel. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/62668/WWPC_6_Dec_2011.pdf

Petersson, S., 1999. Gender Neutral Drafting: Recent Commonwealth Developments. Statute Law Rev. 20, 35–65.

Petersson, S., 1998. Gender Neutral Drafting: Historical Perspective. Statute Law Rev. 19, 93–112.

Pi, G., Schmolka, V., 2000. A Report on Results of Usability Testing Research on Plain Language Draft Sections of the Employment Insurance Act: A Report to Department of Justice Canada and Human Resources Development Canada. https://davidberman.com/wp-content/uploads/glpi-english.pdf

Schmolka, V., 1995. Consumer Fireworks Regulations: Usability Testing, TR1195-2e. Department of Justice Canada.

Schweikart, D., 1990. Gender Neutral Pronoun Redefined. Women's Rights Law Report. 20, 1–9.

Snyder, F., 1993. The Effectiveness of European Community Law: Institutions, Processes, Tools and Techniques. Mod. Law Rev. 56, 19–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2230.1993.tb02852.x

Snyder, F., 1990. New Directions in European Community Law. Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London.

Statsky, W., 1984. Legislative Analysis and Drafting. West Publishing Company, St Paul MN.

Stefanou, C., 2011. Legislative Drafting as a Form of Communication, in H. Xanthaki, ed. Quality of Legislation Principles and Instruments. Nomos, Baden-Baden, pp. 308–320.

Stefanou, C., 2008. Drafters, Drafting and the Policy Process, in S. Stefanou and H. Xanthaki, eds. Drafting Legislation: A Modern Approach. Ashgate, Aldershot, pp. 321–334.

Swift, K., Miller, C., 1980. The Handbook of Nonsexist Writing. Lippincott and Crowell, New York.

Teubner G., 1992. Regulatory Law: Chronicle of a Death Foretold. Soc. & Leg. Stud. 1, 451–475.

Timmermans, C., 1997. How Can One Improve the Quality of Community Legislation? Common Mark. Law Rev. 34, 1229–1257.

United Nations Development Programme, 2003. Drafting Gender-Aware Legislation: How to Promote and Protect Gender Equality in Central and Eastern Europe and in the Commonwealth of Independent States. UNDP, Bratislava. https://iknowpolitics.org/sites/default/files/drafting20gender-aware20legislation.pdf

Voermans, W.J.M., 2009. Concern about the Quality of EU Legislation: What Kind of Problem, by What Kind of Standards? Erasmus Law Rev. 2, 59–95.

Weatherill, S., 2007. The Challenge of Better Regulation, in S. Weatherill, ed. Better Regulation. Hart Publishing, Oxford, pp. 1–18.

Williams, C., 2008. The End of the ‘Masculine Rule’? Gender-Neutral Legislative Drafting in the United Kingdom and Ireland. Statute Law Rev. 29, 139–153.

Wilson, M., 2011. Sir William Dale Annual Memorial Lecture: Gender-Neutral Law Drafting: The Challenge of Translating Policy into Legislation. Eur. J. Law Reform 13, 199–209.

Xanthaki, H., 2014. Drafting Legislation: Art and Technology of Rules for Regulation. Bloomsbury Publishing, London.

Xanthaki, H., 2008. On Transferability of Legislative Solutions: The Functionality Test, in S. Stefanou and H. Xanthaki, eds. Drafting Legislation: A Modern Approach. Ashgate, Aldershot, pp. 1–18.

* Professor of Law and Legislative Drafting, UCL, UK; Dean, International Postgraduate Laws Programmes, University of London, UK; Senior Associate Research Fellow, Sir William Dale Centre for Legislative Studies, Institute of Advanced Legal Studies, UK; and President, International Association for Legislation. Email h.xanthaki@ucl.ac.uk

(1) A statute is the formal expression of legislative policy (Driedger, 1976).

(2) For a first draft of the pyramid, see Xanthaki (2008).

(3) See Timmermans (1997); Commission of the European Communities (2002); also see High Level Group on the Operation of Internal Market(1992); also Office of the Parliamentary Counsel (2011); and Office of the Parliamentary Counsel (2014).

(4) This is Mousmouti’s effectiveness test.

(6) For a full analysis of gender neutral drafting, see Xanthaki (2014), p. 103.

(7) See UNESCO’s Guidelines on Gender-Neutral Language: Desprez-Bouanchaud et al (1999).

(8) From the point of view of legislative expression, experiences of eliminating race from legislative language can be used to guide the drafter in possible ways forward for the elimination of sex and gender from legislative language.

(9) See the statement of the Leader of the House of Commons HC Deb 8 March 2007, c146 WS. See also the debates in the House of Lords in 2013 and 2018: HL Deb 12 December 2013 cols 1004- 1016; HL Deb 25 June 2018 cols 7-9.

(10) See for example section 6 of the UK Interpretation Act 1978.

(11) See OPC, “Gender-neutral drafting techniques”, Drafting Techniques Group Paper 23 (final) (December 2008).

(12) See the examples in the OED and Fowler’s Modern English Usage (Burchfield, 1996).