"We are fighting": Global Indigeneity

and Climate Change

MARTIN PREMOLI[*]

Recently,

numerous islands across the South Pacific have appeared in headlines for their increasingly

acute vulnerability to our global climate crisis.[1]

The most recent climate models predict that if the Earth warms by two degrees

Celsius, many low-lying islands (such as Tuvalu, Solomon Islands, Kiribati, and

the Maldives) will disappear beneath the ocean's rising water levels. Signs of

this possible future have already started to manifest: today, these island

communities face an onslaught of environmental problems linked to climate

change, such as fresh-water shortage, unpredictable and intensified storm

patterns, flooding, coral degradation, and the destruction of crucial foodways.

Even though these island nations have done little to set the global climate

crisis in motion, they are in many cases the first to feel the blowback of

climatological breakdown.

In response to the magnitude of this

crisis, islanders from the South Pacific have developed numerous forms of

aesthetics-based activism, drawing on creative expression to advocate for

climate justice. Their work emphasizes the necessity of bolstering climate

change discourse with questions of social justice and Indigenous sovereignty.

This can be seen, for instance, in the poetry of CHamoru poet, activist, and

scholar Craig Santos Perez. Over the past decade, Perez has emerged as one of

the leading voices from the Pacific for navigating the Anthropocene's submarine

futures. His work is often inspired by his ancestral and personal ties to

Guåhan (Guam), and he has received several prestigious literary awards for his

writing, such as the Pen Center USA/Poetry Society of America Literary Prize

(2011), the American Book Award (2015), and the Hawai'i Literary Arts

Council Award (2017).

Across his oeuvre, Perez draws on and

experiments with poetic form to explore the intersections of colonialism,

climate change, and Indigeneity. His excellent 2020 collection, Habitat

Threshold, serves as a useful case in point. In this collection, he draws

on a range of poetic forms (such as odes, sonnets, haikus, and elegies) to

frame, unsettle, and invigorate numerous environmental issues, including

species extinction, plastics pollution, nuclear toxicity, and food sovereignty.

His poems toggle between local and global scales, allowing for a diversity of

perspectives to emerge. As Eric Magrane writes in his review of Habitat Threshold,

"this is a vital book of ecopoetry: Perez is an essential voice in the face of

the ongoing and relentless intertwining of ecological and social calamities of

the Anthropocene/Capitalocene" (393).

As an example of his climate justice

based approach to Anthropocene discourse, we can turn to the climate change

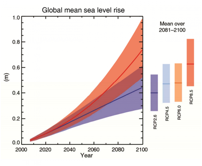

visualization that launches Habitat Threshold. Perez begins his

collection of poems with a seemingly straightforward climate graph. This graph,

charting global sea-level rise, is based on the fifth assessment report

developed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)—an

organization that has deeply influenced the direction, tone, and outcome of

policy and public debates surrounding climate change.[2]

At first glance, Perez's reproduction of the graph appears to simply echo the

information found in the IPCC's fifth assessment report. His graph presents

readers with information pertaining to the issue of long-term sea level rise,

based on scenarios of greenhouse gas concentrations. Following the conventions

of a standard bar chart, the horizontal "X" axis functions as a timeline,

starting in the early 2000s and ending at the year 2100. Meanwhile, the

vertical "Y" axis measures sea level rise in meters. Reading these two axes in

relation to each other allows us to visualize sea level rise as it is projected

to occur in the future.

(Original) (Reproduction by

Perez)

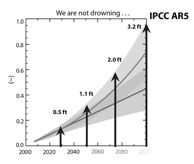

Upon closer inspection, however, we

begin to notice how Perez has made crucial changes to the graph's content and form, pushing readers to re-think the graph's significance.[3]

This is clear, for example, through an examination of the graph's (re)titling. While

the IPCC's visualization of sea-level rise is titled "Global mean sea level

rise," Perez instead opts for a very different header: "We are not drowning..."

Those familiar with climate justice movements in the South Pacific will

immediately recognize this phrase as the rallying cry of the Pacific Climate

Warriors, whose Oceania-based activism protests the ongoing violence of Western

climate imperialism. As stated in an article by 350.org, climate activists

deploy this phrase to combat the "common perception that the Pacific Islands

are drowning from sea-level rise" and to remind people that "it's not yet time

to give up on the Islands" (Packard, "We are not drowning"). The effect of

Perez's re-titling is thus deeply significant: through this new (and

anti-colonial) title, Perez's graph challenges the reductionist tendencies of

the IPCC's official climate visualization, which reduces the complexity of

interactions between climates, environments, and

societies in order to predict a singular—and typically

apocalyptic—climate-changed future (Hulme, "Reducing the Future to

Climate" 247). (This is what geographer Mike Hulme has characterized as

"climate reductionism," which might be viewed as a variant of climate

determinism.) Rather, his graph insists on the importance of recognizing that

the future is not foreclosed and that struggles for life are still of paramount

importance.[4]

Through this formal innovation, then,

Perez points toward the disruptive and empowering potential of Indigenous

activism in the movement toward climate justice. His poem does not denounce or

deny the insights offered by positivist models of knowledge production (this

would be a dangerous maneuver in our current political climate), but it does

push back against the overriding tendencies toward extinction that so often

characterize graphs on climate change.[5] The poem thus demonstrates the potential that can

come from "entangling epistemologies": that is, integrating Eurowestern

positivism with "ways of knowing based in speculation, multigenerational

experience, social relations, metaphor and story, and the sensing and feeling

body" (Houser 5).[6] These "other

ways of knowing," Perez suggests, are crucial for combating climate injustice

and for preserving the lifeways of frontline communities in the South Pacific.

Of course, Perez is not alone in seeking

climate justice for Indigenous communities across Oceania. Numerous poets from

the region have highlighted the simultaneous risk and empowerment of Pacific

Islanders when faced with "sinking islands." In 2014, Marshallese poet and

activist, Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner, was invited to speak on the imperiled position

of the Marshall Islands for the opening ceremony of the United Nations

Secretary General's Climate Summit. During her opening remarks, Jetñil-Kijiner

argues that we "need a radical change in course" if we hope to tackle the

global climate crisis (1:43). She powerfully

elaborates on this point through a reading of her poem "Dear Matafele Peinam,"

an ode to her seven-month-old daughter and their vanishing home island. As

another example, during the UN Climate Conference in Paris, four spoken word poets—Terisa

Siagatonu, John Meta Sarmiento, Isabella Avila Borgeson, and Eunice

Andrada—performed creative pieces that called attention to the everyday

realities of climate disaster, while demanding a global response to the issue.

In her poem "Layers," Siagatonu asks her audience why "saving the environment rarely

means saving people who come from environments like mine, where black and brown

bodies are riddled with despair" (1:01).

While poetry has been a particularly

rich site for climate justice advocacy, artists from the South Pacific have

worked across the spectrum of aesthetic forms. This includes theatre and

performance-based awareness projects (as seen in the performance Moana: The

Rising of the Sea), film and documentary (see Anote's Ark), and

other modes of literary expression (Keri Hulme's short story "Floating Worlds,"

for instance). Rather than fulfilling the victimization narrative desired by

the traditional media, these cultural interventions highlight the simultaneous

risk and empowerment of Pacific Islanders when faced with "sinking islands"

(Ghosh "Poets Body as Archive"). And they foreground the values and insights

offered by Indigenous communities in combating the climate crisis. Through

their work, then, these artist-activists challenge, nuance, and re-write

narratives about the climate crisis—their work has become crucial for

navigating what Elizabeth DeLoughrey terms "the submarine futures of the

Anthropocene" ("Submarine Futures").

I begin with this quick overview of recent Oceania-based

climate activism and artistic uprisings as they speak to the motivating

concerns at the heart of this special issue of Transmotion. Around the

world, Indigenous communities are leading movements to redress and counteract

the violence of anthropogenic climate change, along with its driving forces of

colonialism and capitalism. These movements critically reflect on how Indigenous

peoples define their relationships to the land and water, to other humans and

non-humans, and to history and time in order to push back against the genocidal

wave of ecological violence. As

Jaskiran Dhillon puts it,

Indigenous peoples are challenging

structures of contemporary global capitalism, standing up and speaking out to

protect the land, water, and air from further contamination and ruination, and

embodying long-standing forms of relationality and kinship that counter Western

epistemologies of human/nature dualism. Indigenous peoples are mapping the contours

of alternative modes of social, political, and economic organization that speak

to the past, present, and the future—catapulting us into a moment of

critical, radical reflection about the substantive scope and limitations of

"mainstream environmentalism" (1).

This

issue of Transmotion builds on these insights, focusing on the

innumerable and profoundly consequential ways that Indigenous peoples have

shaped and contributed to debates surrounding the Anthropocene, particularly

through forms of storytelling and cultural production.

Our focus on stories resonates with

Donna Haraway's claim that "it matters what stories we tell to tell other

stories with; it matters what knots knot knots, what thoughts think thoughts,

what descriptions describe descriptions, what ties tie ties. It matters what

stories make worlds, what worlds make stories" (12). In the spirit of this

sentiment, our contributors examine stories from a plurality of aesthetic forms, such as literature,

photography, film, and other related modes of creative expression. Drawing upon

their knowledge as scholars of literary and cultural studies, our contributors

tease out the ways in which Indigenous storytelling depicts the complex

negotiations of "nature" and "culture" in the Anthropocene. This special issue thus takes seriously

the Anishnaabe understanding that "stories are vessels of knowledge" and that,

as such, they "carry dynamic answers to questions" posed by various Indigenous

communities (Doerfler et al.)

Given the global scope of the climate

crisis, this issue of Transmotion focuses on the significance of

Anthropocene narratives in a global Indigenous arena. In operationalizing a

trans-Indigenous framework, we support Chadwick Allen's assertion that we must

undertake Indigenous-centered scholarship that reads Indigenous texts in

comparative terms, rather than in relation to a Eurowestern canon. Following

Allen, our aim is "not to displace the necessary, invigorating study of

specific traditions and contexts but rather to complement these by augmenting

and expanding broader, globally Indigenous fields of inquiry" (xiv). Across

disparate locales, we consider the potential that an anti- and decolonial

Anthropocene discourse can hold for transnational solidarity and global

Indigenous sovereignty. Our contributors reflect on how Indigenous artists and

activists reconcile the local exigencies of their environment with the global

discourse on climate change. Through

our deployment of a trans-Indigenous methodology, we hope to offer a

thought-provoking venue to explore the diverse and interrelated forms of

Indigenous creativity from across the globe.

In what follows, I begin by overviewing

some of the main interventions Indigenous thinkers have made in relation to

Anthropocene discourse, emphasizing their strategies for decolonizing,

problematizing, and unsettling dominant perspectives in this growing field.

This is not a comprehensive summary of the field, rather it is a survey

featuring some of the voices that have contributed to this vibrant conversation.

With this context established, I turn to the growing dialogue between

eco-critical and Indigenous literary studies to consider how these fields have

increasingly dialogued since the acceleration of Anthropocene thinking, and I

provide an overview of the scholarly contributions that comprise this special

issue.

Decolonizing the Anthropocene

The central theme of this issue has inspired a

significant amount of critical interest in recent years. Before discussing how aesthetic works,

in particular, have responded to discourse on the Anthropocene, it's useful to

map out how Indigenous scholars from a variety of disciplines have productively

engaged with and problematized discourse on the Anthropocene. The term

"Anthropocene" was coined and popularized by ecologist Eugene Stoermer and

atmospheric chemist Paul Crutzen at the turn of the 21st century. In

their initial formulation of this term, the Anthropocene designates a newly

proposed geological epoch in which humans are considered a collective

geophysical force, responsible for drastic changes to the planet's overall

habitability. For the first time in Earth's history, humankind had altered the

planet's deep chemistry—its atmosphere, lithosphere, hydrosphere, and

biosphere—in massive, long-lasting ways. Crutzen and Stoermer dated this

rupture to the late eighteenth century beginnings of the industrial revolution,

when unprecedented developments in trade, travel, and technology resulted in a

drastic increase in global concentrations of carbon dioxide and methane (which

are evident in recent analyses of air trapped in polar ice). Along with this

important historical moment, they further identify a "Great Acceleration" in

the mid-twentieth century, when human population, consumption, and greenhouse

gas emissions all skyrocketed. For these reasons, they argue that the "impact

of human activities on earth [across] all scales" has made it "more than

appropriate to emphasize the central role of mankind in geology and

ecology" (17).

Since its early formulation, the term has become the subject

of ever-growing critical debate. In particular, numerous critics have taken

issue with the term's tendency for generalization and abstraction: Crutzen and

Stoermer's hypothesis frames climate change as a problem caused by the human

species writ large (this is evident in the line referenced above). Moreover, their

framework obscures the ways in which environmental violence is

disproportionately created and differentially distributed, particularly along

the lines of race, class, and gender. To counteract these tendencies, scholars

across disciplines have theorized spinoff "-cenes," ones that more closely

inspect the historical processes and epistemologies that directly contributed

to anthropogenic climate change. Jason Moore's notion of the "Capitalocene"

identifies the global capitalist system—with its prioritization of

limitless growth and "cheap nature"—as the primary culprit in the

creation of climate vulnerability. Another influential alternative, the

"Plantationocene," links climate change to the transatlantic slave trade and

its afterlives. Developed by Sophie Moore and collaborators, this term

confronts the enduring legacies of plantations and unpacks the ways that these

integral sites were produced through processes of intensive land usage, land

alienation, labor extraction, and racialized violence (first indentured

servitude, and later slavery). These terms thus highlight the reality that "we

may all be in the Anthropocene, but we are not all in it in the same way"

(Nixon 8). And, moreover, they speak to the crucial implications of how we

define, delimit, and narrate our ecological and climatological crisis.[7]

Writing from an Indigenous studies

framework, Zoe Todd (Métis) and Heather Davis have offered one of the most

compelling reconceptualizations of the term. In their article, "On the

Importance of a Date, or Decolonizing the Anthropocene," they examine the

ways that climate change discourse might productively shift if we reconsider

the Anthropocene's origin point. Challenging the typical mid-20th century

start-point, Davis and Todd propose linking the Anthropocene to the

Columbian exchange (1610). This is an important historical flashpoint, they

explain, for two reasons:

The first is that the amount of plants

and animals that were exchanged between Europe and the Americas during this

time drastically re-shaped the ecosystems of both of these landmasses, evidence

of which can be found in the geologic layer by way of the kinds of biomass

accumulated there. The second reason, which is a much more chilling indictment

against the horrifying realities of colonialism, is the drop in carbon dioxide

levels that can be found in the geologic layer that correspond to the genocide

of the peoples of the Americas and the subsequent re-growth of forests and

other plants (766).

In

other words, this moment is significant because it offers the kind of

"evidence" that geologists and scientists need for determining the onset of a

new geologic epoch. When large-scale events have occurred in the earth's deep

history (such as global cooling events), they leave a geologic marker that is

visible in the earth's sedimentary strata—this is referred to as a

"golden spike." In order to determine if the Anthropocene constitutes a new

epoch, scientists have endeavored to trace and locate a new golden spike within

the earth's geologic bedrock (and indeed, multiple "golden spikes" have been

proposed). As Kathryn Yusoff notes, this method operates as a disciplinary

endeavor to geologically map the material relation of space and time according

to stratigraphic principles and scientific precedents—and it is therefore

grounded in the distinctly positivist values inherent to a Eurowestern

scientific system (Yusoff, Chapter 2).

Todd and Davis find the aforementioned

moment to be significant for other reasons, however. Using a date that

coincides with colonialism in the Americas, they explain, allows us to

understand the nature of our ecological crisis as inherently ascribed to a

specific ideology that is animated by proto-capitalist logics based on

extraction and accumulation through dispossession. This process also entailed

the disruption of the kin relations that characterize Indigenous perspectives

and forms of knowledge. As they put it, the Anthropocene registers "a severing

of relations between humans and the soil, between plants and animals, between

minerals and our bones" (770).

These logics of accumulation and

dispossession, however, are not sequestered to a remote past. As Todd and Davis

observe, they continue to shape the present day, producing our current era of

growing climate destabilization. Today, the economic infrastructures of

settler-colonies around the world depend on extractive industries: natural

resources are transported to international markets "from oil and gas fields,

refineries, lumber mills, mining operations, and hydro-electric facilities

located on the dispossessed lands of Indigenous nations" (Coulthard "Thesis

2"). In many cases, cooperation between the federal government and private

businesses paves the way for these extractive processes, further cementing

settler control over the land while undermining Indigenous authority and sovereignty.[8]

In recent years, this has led to the frightening manifestation of what Ashley

Dawson describes as "extractivist populism," wherein the bigotry and repression

of authoritarian populism has combined with and amplified the ecocidal

intensification of resource extraction—both in the name of "progress" and

the "people's good" (Amatya and Dawson 6). These ongoing instances of energy

and resource extraction consistently highlight the recursive or cyclical nature

of climate violence, which cuts across linear conceptions of time and

straightforward notions of progress. To adapt the

words of Patrick Wolfe, settler colonialism as climate change is a structure

and not an event (388).

Beyond identifying capitalism and

colonialism as the core problematics of the Anthropocene, Indigenous scholars

have also stepped forward as central figures in providing alternatives to

climate colonialism, offering "both knowledge and leadership in understanding

and addressing environmental crises" (Deloria et al. 13). The Potawatomi

scholar and activist Kyle Whyte has dedicated much of his work to crafting what

he calls "Indigenous climate change studies," an Indigenous-based approach to

climate change. His formulation of Indigenous climate change studies is

supported by three basic tenets. First, climate change is an intensification of

the ways colonial structures of power have always shaped environments. Second,

Indigenous communities can better prepare for climate change by renewing

Indigenous knowledges, including languages, sciences, and forms of human and

nonhuman kinship. Third, the perspectives of Indigenous peoples who are already

adapting to the postapocalyptic conditions of colonialism changes the ways

these communities imagine futures affected by climate change. Together, these

elements yield a mode of praxis wherein one "perform[s] futurities that

Indigenous persons can build on in generations to come. [It is] guided by our

reflection on our ancestors' perspectives and on our desire to be good

ancestors ourselves to future generations (160).

Instances of Indigenous climate change

studies have proliferated as climate breakdown has accelerated, signaling the

salience and necessity of this approach. In one example, Whyte describes a

collaborative encounter between the state of Alaska and Koyukon people of

Koyukuk-Middle Yukon region in the Arctic. In order to navigate unprecedented

climatic shifts in the region, the state proposed hunting regulations on moose

that would hamper Indigenous harvesting practices. As an alternative, Koyukon

youth and elders drew upon their traditional knowledge of the seasonal round to

create an alternative system that displayed their own understanding of

seasonality. Ultimately, their seasonal wheel demonstrated that "shifting the

moose hunting season later so as to correspond with the Indigenous view of

seasonality makes more sense than the date proposed by state and federal

regulators" (218). The Yukon example thus illuminates the promising potential

of Indigenous climate change studies, and it illustrates the central role that

Indigenous self-determination must play in planning for climate change

adaptation.

Importantly, Whyte and other Indigenous

scholar-activists, have cautioned that these practices should not be utilized

as tools for last-ditch efforts at climate recovery. Numerous attempts at "integrating"

Indigenous knowledge systems (such as the work found in the "Our Common Future"

report) have often been reductive and appropriative in their approach. As

Leanne Simpson observes, Eurowestern environmentalists often believe that

"traditional knowledge and indigenous peoples have some sort of secret of how

to live on the land in a non-exploitative way that broader societies need to appropriate"

("Dancing the World into Being"). This kind of approach has the tendency to

romanticize Indigenous knowledge, reproducing stereotypes of the "ecological

Indian"—the "traditional" Native who lives in harmony with the untouched

environment. Moreover, Eurowestern approaches to Indigenous knowledge often

operate through a logic of intellectual extraction, in which knowledge is

removed from its context, from its originary language, and from traditional

knowledge holders. To counter the extractive and fetishistic tendencies of

mainstream environmentalism, it is crucial to cultivate a model of

"responsibility"—an environmentalist approach founded on respectful,

long-standing relationships with Indigenous people and with place ("Dancing the

World into Being").[9]

Finally, it is

crucial to recognize that decolonizing

Eurowestern environmentalisms is only part of what is necessary for advancing

an ecological model grounded in responsibility and humility. As Eve Tuck and K.

Wayne Yang explain (and as is suggested by both Whyte's and Simpson's emphasis

on place), decolonization must agitate for practices of restorative land

justice. In their article "Decolonization is not a metaphor," Tuck and Yang

argue that "decolonization in the settler colonial context must involve the

repatriation of land simultaneous to the recognition of how land and relations

to land have always already been differently understood and enacted; that is, all

of the land, and not just symbolically" (7). For Tuck and Yang, decolonization

cannot function as a stand-in for "the discourse of social justice"; instead,

it must aim to recover the Indigenous lands that were stolen by settlers

through numerous and ongoing appropriative strategies. In turn, land recovery

would then allow for the resurgence of "Indigenous political-economic

alternatives [that] could pose a real threat to the accumulation of capital in

Indigenous lands..." (Coulthard "Thesis 2").[10]

Such insights are crucial for developing an anti-colonial approach to the

Anthropocene: these scholars help us understand that implementing Indigenous

modes of environmental knowledge—which are tethered to

place—necessitates the dismantling of extractive capitalism and the

repatriation of Indigenous lands. Ignoring this reality impedes the restoration

of the life-ways, practices, and kinship networks that are necessary for living

responsibly in the midst of profound ecological change.

As this overview suggests,

Indigenous studies has already proven to be a pivotal site of exchange for

conversations surrounding the Anthropocene—and this critical work is only

continuing to grow and evolve as the climate crisis spins further out of

control. The various activists and intellectuals I have discussed above allow

for a fuller (and more accurate) picture of our current geological epoch to

come into view. Their work powerfully demonstrates the numerous ways that

capitalism and settler colonialism have ushered in our warming world—and

they illustrate how these violent logics are ongoing and evolving. Just as

importantly, however, these thinkers also emphasize how efforts for resistance

and resurgence are being led by Indigenous communities around the world. In

doing so, they push for an honest conversation regarding how we have found

ourselves in the throes of global environmental catastrophe—and,

possibly, how we can imagine a future freed from domination, and built instead

on a foundation of climatological justice.

EH, Indigenous Aesthetics,

and Climate Justice

The work of imagining futures anchored in climate

justice has been a primary endeavor for scholars in the environmental

humanities (and the subdiscipline of eco-criticism). As an interdisciplinary

(and sometimes anti-disciplinary) field, the environmental humanities "envision

ecological crises fundamentally as questions of socioeconomic inequality,

cultural difference, and divergent histories, values, and ethical frameworks"

(Heise 2). Rather than insist on the belief that science, data, or technology

can awaken us to the severity of our climate's breakdown, scholarship in EH

insists on emphasizing the political, social, cultural, and affective forms

that the climate problem takes in different communities, cultures, and

imaginaries (2). While scholars in EH acknowledge the importance of scientific

understanding and technological problem-solving, they also remind us that these

discourses are themselves colored by the disciplines that grant them power, and

that they "stand to gain by situating themselves in [a] historical and sociocultural

landscape" (2). The reality of this notion comes into clear view when we

consider the ongoing nature of the climate change "debate," particularly as it

has played out within the United States. As scholars such as Mike Hulme and

Dale Jamieson have shown, doubling down on the insights generated by the

scientific community does little to shift social and political opinion about

the climate crisis, especially when these insights remain disconnected from the

larger cultural contexts and histories that influence our ideas and experiences

of the climate (3). To dream of more sustainable futures, then, we must tap

into the capacities of narrative (and other humanistic disciplines) for

reimagining "the environment" and humankind's place within it.[11]

This special issue

approaches the environmental humanities from an Indigenous-oriented angle,

combing EH's interests in climate and narrative with the kinds of questions and

concerns I've outlined in this introduction's second section.[12] Scholars working at this critical

crossroads have already begun exploring some of the most crucial concerns

raised by Indigenous creative work. Much critical analysis, for instance, has

examined how different genres (such as the gothic, dystopian, or speculative)

assist us in navigating the specific epistemological and ontological challenges

posed by the jarring disruptions of the Anthropocene (Anderson, DeLoughrey, Dhillon). Other

work has documented the ways that Indigenous narratives intersect with and

inflect forms of environmental activism and protest (Cariou, Kinder, Streeby).

A growing body of literature considers the archival function of Indigenous

storytelling, tracing how these stories retain and transmit ecological

knowledge across long swathes of time (LeMenager, Perez). Other work has

discussed some of the ways that Indigenous narratives foreground questions of

multi-species kinship, gender and sexual equality, anti-racism, and

environmental justice in order to advance more equitable climate futures

(Adamson, Goeman). And most recently, a collection of scholars encourage us to

re-consider the

utility of the Anthropocene metric in and of itself: "the Anthropocene is a

narrative, one cooperatively composed and begging now for crowdsourced

revision, with sequels that are not linear or conclusive but alternately

recursive and speculative, plodding and precipitous, stale and untried" (Benson

Taylor 10). These are only some of the issues and insights examined by an

Indigenous-oriented ecocriticism—one that works toward the development of

a decolonial climate movement on a global scale.

Our special issue aims to further

explore such preoccupations and discover new points of critical reflection. We begin with an essay by Kasey Jones-Matrona on Jennifer Elise Foerster's Bright Raft in the Afterweather. In this essay, Jones-Matrona examines how Foerster's

poetry draws on Indigenous scientific literacies (that account for both human

and nonhuman knowledge) to re-map Creek lands, histories, and futures in the

Anthropocene. Jones-Matrona then connects these re-mapped cartographies to the

prospect of healing, arguing that, even in works with catastrophic themes and

settings, healing is a crucial aspect of Indigenous futurist work. In centering

the significance of healing, Jones-Matrona elucidates and "amplifies an

Indigenous-specific notion of the Anthropocene."

Through an examination of Ciro Guerra's Embrace of the Serpent, Holly May Treadwell explores and further develops

the notion of the Capitalocence (as theorized by Jason Moore). As Treadwell

explains, Embrace

of the Serpent rejects the

notion of the Anthropocene and its homogenous view of "human" activity,

explicitly demonstrating that it is specifically capitalism as an extension of

colonialism that is having such detrimental and violent effects on the climate.

Treadwell focuses specifically on the way that the Capitalocence, as depicted

in Embrace

of the Serpent, paves the

way for extinction on three fronts: "the extinction of people via forced labor,

decimation of land, murder, and dispossession; the extinction of Indigenous

cultures, comparing the personification, conservation, and kinship with nature,

to capitalism's commodification, exploitation, and demonization of nature; and

the extinction of nature itself via its domination and cultivation." Treadwell

closes their essay by asking how Indigenous knowledge might challenge the wave

of extinction propelled by the capitalization of nature.

Abdenour Bouich's essay on Tanya Tagaq's novel Split Tooth looks at the ways in which Tanya Tagaq's formally

inventive work critiques the destructive "developmental" ethos of colonial

capitalist modernity, which targets Indigenous Inuit peoples of Canada. In

particular, Bouich's reading focuses on the text's depiction of the ecological

disasters provoked by resource extraction and global warming brought about by

global capitalism and, in particular, Canadian capitalist expansionism in the

Arctic region. While accounting for the scale of such petro-violence, Split Tooth, Bouich contends, also employs

a variety of literary forms to catalyze the resurgence and the recovery of

"Indigenous ontologies, epistemologies, and politics that have long been

dismissed by colonial discourses and narratives." In doing so, the text can be

read as what Daniel Heath Justice calls an Indigenous "wonderwork"—a

genre-crossing text grounded in the resilient worldviews of the Indigenous

Inuit of Nunavut.

In their essay on Celu Amberstone's novella

"Refugees," Fernando Pérez Garcia also considers the affordances of formal

experimentation, focusing on the decolonial possibilities of Indigenous

futurism. The article draws on Leanne Betasamosake Simpson's

and Glenn Coulthard's work on Indigenous resurgence to explore how the novella

comments on Canada's exploitative economic system, which relies heavily on the

extraction of natural resources and the ongoing dispossession of Indigenous

communities. According to Garcia, Indigenous futurist fiction not only provides

"Indigenous meaning to past and ongoing colonial experiences," but it projects

an Indigenous presence and epistemology into the future. "Refugees," in

particular, acts as a channel for the expression of possible collective

self-recognition through relationships based on reciprocity between human and

non-human forms of life. Such an imaginative endeavor—which envisions

sovereignty from Indigenous perspective—is central for conceptualizing

alternatives to environmental collapse.

Similar concerns are taken up by Kyle Bladow, in their

essay on Louise Erdrich's speculative novel, Future Home of the Living God. Bladow's essay assesses how "recent literary

depictions of Indigenous futurity coincide with grassroots activism that has

been ongoing for generations and that is finding new iterations in current

movements for climate justice and against settler colonial resource extraction."

Bladow coins the useful term "oblique cli-fi" to describe recent

post-apocalyptic novels, written by Indigenous writers, which feature

catastrophes that are not necessarily caused by climate change (but which have

been considered under a cli-fi rubric due to the increasingly close

relationship between climate change and catastrophe). Erdrich's oblique cli-fi

shows how responsibilities toward land and kin were never contingent upon permanent,

unchanging ecologies but instead exist in states of dynamism and change,

allowing for flexible re-creations of environmental stewardship. From this

perspective, Future

Home of the Living God envisions hopeful

prospects for a reservation community in an otherwise dystopian narrative.

Finally, Isabel Lockhart's contribution considers

the diverse work of Métis writer, scholar, documentary filmmaker, and

photographer Warren Cariou as a formal counterpoint to dominant representations

of the Athabasca tar sands. In contrast to the aerial aesthetics favored

by Canadian photographers, such as Edward Burtynsky and Louis Helbig, Cariou

favors literary and aesthetic forms that approximate the feel and smell of

tar. Crucially, this "from below" perspective on the tar sands not only seeks

to make sensible the impacts of the oil industry, but it also illuminates

Indigenous presence against the settler social relations that underpin

extraction in the region currently known as Alberta. Lockhart's essay thus

concludes with an examination of how Cariou develops an alternate, Indigenous

politics of action that switches, as they put it, from representation of bitumen

to relationships with bitumen. "By intervening directly in the use and

meaning of bitumen," Lockhart argues, "Cariou's practices offer us an

alternative to the terms of urgency, visibility, and action that so often frame

climate art."

These reflections, anchored in the rich field of

Indigenous literary studies, can help re-signify and reorient interdisciplinary

conversations about the Anthropocene, particularly when it is framed as a

product of longstanding colonial violence. Moreover, these contributions seek

to emphasize the necessity of centering Indigenous voices in conversations

about climate justice, sovereignty, and environmental sustainability, while

modeling generative approaches and methodologies for this endeavor. Such work

is crucial for attending to life-destroying and world-creating effects of the

colonial Anthropocene.

Works

Cited

Adamson, Joni. American Indian Literature,

Environmental Justice, and Ecocriticism: The Middle Place. Tucson: U of

Arizona P, 2001.

Alaimo, Stacy. Exposed: Environmental Politics

and Pleasures in Posthuman Times. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 2016.

Allen, Chadwick. Trans-Indigenous:

Methodologies for Global Native Literary Studies. University of Minnesota

Press, 2012.

Amatya, Alok and Ashely Dawson, "Literature in an

Age of Extraction: An Introduction." Modern Fiction Studies, 66:1, 2020,

1-19.

Anderson, Eric Gary, and Melanie Benson Taylor.

"Letting the Other Story Go: The Native South in and beyond the Anthropocene."

Native South, 12, 2019, 74–98.

Benson Taylor, Melanie. "Indigenous Interruptions in

the Anthropocene." PMLA, 136:1, 2021, 9-16.

Cariou, Warren, and Isabelle St-Amand.

"Environmental Ethics Through Changing Landscapes: Indigenous

Activism and Literary Arts." Introduction. Canadian

Review of Comparative Literature / Revue Canadienne de Littérature Comparée,

44:1, 2017, 7-24.

Coulthard, Glenn. "Thesis, 2: Capitalism No More." The

New Inquiry, 13 Oct. 2014,

https://thenewinquiry.com/thesis-2-capitalism-no-more/.

Crutzen, Paul J, and Eugene F. Stoermer. "The

'Anthropocene'." International

Geosphere-Biosphere Programme (IGBP) Global Change Newsletter, 41, 2000,

17-18.

Davis, Heather, and Zoe Todd. "On the Importance of

a Date, or Decolonizing the Anthropocene." ACME:

An International Journal for Critical Geographies, 16:4, 2017, 761-780.

Deloria, Philip, et al. "Unfolding Futures:

Indigenous Ways of Knowing for the Twenty-First Century." Dædalus: Journal

of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 147:2, 2018, 6-16.

DeLoughrey, Elizabeth M. Allegories

of the Anthropocene. Durham: Duke UP, 2019.

---. "Submarine Futures of the Anthropocene." Comparative

Literature, 69:2, 2017, 32-44.

Dhillon, Grace. Walking the Clouds: An Anthology

of Indigenous Science Fiction. The U of Arizona P, 2012.

Dhillon, Jaskiran. "Indigenous Resurgence,

Decolonization, and Movements for Environmental Justice." Environment and

Society, 9:1, 2018, 1-5.

---. "What Standing Rock Teaches Us About

Environmental Justice." Social Sciences Research Council, 5 Dec. 2017, https://items.ssrc.org/just-environments/what-standing-rock-teaches-us-about-environmental-justice/.

Doerfler, Jill, Niigaanwewidam James Sinclair, and

Heidi Kiiwetinepinesiik Stark, editors. Centering Anishinaabeg Studies:

Understanding the World Through Stories. Michigan State UP, 2013.

Goeman, Mishuana. Mark My Words: Native

Women Mapping Our Nations. U of Minnesota P, 2013.

Ghosh, Kuhelika. "Poets Body as Archive Amidst a

Rising Ocean." Edge Effects, 17 Nov. 2020,

https://edgeeffects.net/kathy-jetnil-kijiner/.

Goldenberg, Suzanne. "Just 90 Companies Caused

Two-Thirds of Man-Made Global Warming Emissions." The Guardian, 20 Nov.

2013,

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2013/nov/20/90-companies-man-made-global-warming-emissions-climate-change.

Haraway, Donna J. Staying with the Trouble:

Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Duke UP, 2016.

Heise, Ursula. 'Introduction: Planet, Species,

Justice—And the Stories We Tell about Them." The Routledge Companion

to Environmental Humanities, edited by Jon Christensen, Ursula Heise, and

Michelle Niemann, Routledge, 2017.

Houser, Heather. "Climate Visualizations: Making

Data Experiential." The Routledge Companion to the Environmental Humanities,

edited by Jon Christensen, Ursula Heise, and Michelle Niemann, Routledge, 2017,

358-368.

---. Infowhelm: Environmental Art and Literature

in an Age of Data. Columbia UP, 2020.

Hulme, Mike. "Meet the Humanities." Exploring

Climate Change through Science and in Society, edited by Mike Hulme,

Routledge, 2013, 106-109.

---. "Reducing the Future to Climate: A Story of

Climate Determinism and Reductionism." Osiris 26:1. (2011).

Jetñil-Kijiner, Kathy. "Statement and poem by Kathy

Jetñil-Kijiner, Climate Summit 2014 - Opening Ceremony." YouTube,

uploaded by United Nations, 23 Sept. 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mc_IgE7TBSY.

Kinder, Jordan. "Gaming Extractivism: Indigenous

Resurgence, Unjust Infrastructures, and the Politics of Play in Elizabeth

LaPensée's Thunderbird Strike." Canadian Journal of Communication, 46:2,

2021, 247-269.

Klein, Naomi. "Dancing the World into Being: A

Conversation with Idle No More's Leanne Simpson." Yes! Magazine, 6 Mar,

2013, https://www.yesmagazine.org/social-justice/2013/03/06/dancing-the-world-into-being-a-conversation-with-idle-no-more-leanne-simpson.

LeMenager, Stephanie. "Love and Theft; or,

Provincializing the Anthropocene." PMLA, 136:1, 2021, 102-109.

Lewis, Simon L., and Mark A. Maslin. "Defining the

Anthropocene." Nature, 519.7542 (2015): 171–180.

Magrane, Eric. "Habitat Threshold. By Craig

Santos Perez." ISLE: Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment,

8:1, 2021, 393-394.

McGregor, Deborah. "Coming Full Circle: Indigenous

Knowledge, Environment, and Our Future." The American Indian Quarterly,

28:3&4, Summer/Fall 2004, 385-410.

Moore, Jason W. "Introduction." Anthropocene or

Capitalocene? Nature, History, and the Crisis of Capitalism, edited by

Jason W. Moore. Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2016, 1-11.

Moore, Sophie, et al "The Plantationocene and

Plantation Legacies Today." Edge Effects, 22 Jan. 2019,

https://edgeeffects.net/plantation-legacies-plantationocene/.

Nixon, Rob. "The Anthropocene: The Promise and

Pitfalls of an Epochal Idea." Future Remains: A Cabinet of Curiosities for

the Anthropocene. Ed. Gregg Mitman, et al. U of Chicago P, 2018.

Oh, Rebecca. "Making Time: Pacific Futures in

Kiribati's Migration with Dignity, Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner's Iep Jaltok,

and Keri Hulme's Stonefish." Modern Fiction Studies, 66:4, 2020,

597-619.

Packard, Aaron. "350 Pacific: We are not drowning.

We are fighting." 350.org, 17 Feb, 2013,

https://350.org/350-pacific-we-are-not-drowning-we-are-fighting/.

Perez, Craig Santos. Habitat

Threshold. Omnidawn Publishing, 2020.

Johns-Putra, Adeline. Climate

and Literature. Cambridge University Press, 2019.

Siagatonu, Teresa. "Layers – Teresa

Siagatonu." YouTube, uploaded by Internationalist, 8 Dec. 2015,

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7glgz-mUwm0.

Streeby, Shelley. Imagining the Future of

Climate Change: World-Making through Science Fiction and Activism.

University of California Press, 2018.

TallBear, Kim. "Failed Settler Kinship, Truth and

Reconciliation, and Science." Indigenous

Science Technology Society, 16 March 2016, indigenoussts.com/failed-settler-kinship-truth-and-reconciliation-and-science/.

Tuck, Eve and K. Wayne Yang. "Decolonization is Not

a Metaphor." Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 1:1, 2012,

1-40.

Wenzel, Jennifer. The Disposition of Nature:

Environmental Crisis and World Literature. Fordham UP, 2019.

Whyte, Kyle Powys. "Indigenous Climate Change

Studies: Indigenizing Futures, Decolonizing the Anthropocene." English Language Notes, 55:1-2, 2017,

153-162.

---. "Our Ancestors' Dystopia Now: Indigenous

Conservation and the Anthropocene." The Routledge Companion to the

Environmental Humanities, edited by Jon Christensen, Ursula Heise, and Michelle

Niemann, Routledge, 2017, 206-215.

Wolfe, Patrick. "Settler Colonialism and the

Elimination of the Native." Journal of Genocide Research, 8:4, 2006, 387-409.

Yusoff, Kathryn. A Billion Black Anthropocenes or

None. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2018.