Introduction: Indigeneity, Survival, and

the Colonial Anthropocene

MARTIN PREMOLI

The

past decade has given rise to a vast literature that explores the dynamics

between climate justice and activism, environmental knowledges, and Indigenous

storytelling in the colonial Anthropocene. A recent issue in the PMLA, for

example, discusses how the "dialectic of Indigeneity" offers "an abiding

refusal to surrender to either the limits or the logics of this ruined world"

and "provides a map of untraveled routes rather than fallow destinations" (Benson

Taylor 14). Moreover, in their 2017 essay, "Environmental Ethics through

Changing Landscapes: Indigenous Activism and Literary Arts," Warren Cariou and

Isabelle St-Amand "explore themes of environmental ethics and activism in a

contemporary context in which resource extraction and industrialization are

increasingly being countered by indigenized forms of thought and action" (9).

And, to cite a final example, the collection Ecocriticism and Indigenous

Studies "takes the pulse of current Indigenous artistic diversity and

political expression" to examine how these forms "render ecological

connections" visible for diverse audiences (Adamson and Monani 5). These various

texts speak to a growing conversation amongst Indigenous scholars and allies about

our increasingly urgent environmental crisis—and the capacities of

artwork and cultural production for engaging with this dire issue.

Part I of this special issue pursued and

expanded on several of the insights highlighted above. Our contributors

examined the disruptive and empowering potential of Indigenous storytelling in

the movement toward—and realization of—global climate justice. In

this special issue's second installment, we continue this line of exploration. To

introduce this special issue's most pressing concerns, I'd like once more to

turn to the poetry of Chamorro poet, scholar, and activist, Craig Santos Perez.

As before, I will be focusing on one of his poems from his collection Habitat

Threshold, which introduces questions of catastrophe, entanglement,

kinship, survival, and healing—questions that are attended to by the

essays that populate this second issue.

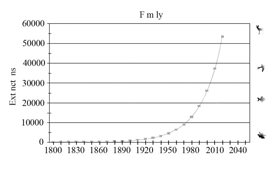

This poem, reproduced below, depicts the

increasing frequency of species extinction in the colonial Anthropocene. This extinction

event, known as the Holocene extinction, figures as the most recent mass

extinction event of our earth's history. Scientists and scholars have suggested

that mass extinction events share three common characteristics. Firstly, they

are necessarily global in scope, and thus not determined or constrained by

regional parameters or borders. Secondly, they occur when extinction rates rise

significantly above background levels of extinction; or, in other words, they

occur when the loss of species rapidly outpaces the rate of speciation. And

finally, within a geological temporal framework, they occur across a

geologically "short" period of time (the "event" might last for thousands of

years, appearing to be quite slow from a human perspective). What's unique about the Holocene

extinction, however, is that our

present crisis is the first to have a human origin point. "Right now,"

Elizabeth Kolbert writes in her study on the topic, "we are deciding, without

quite meaning to, which evolutionary pathways will remain open and which will

forever be closed. No other creature has ever managed this, and it will,

unfortunately, be our most enduring legacy" (88).[1]

Perez visually represents and complicates this "legacy"

through several creative innovations. The graph's title offers us a useful

starting point. Rather than use a more conventionally "scientific" word for his

poemodel (such as "Species," for instance), Perez opts for a more intimate and

familiar choice: "F m ly" (family). By referring to these non-human animals as

family, Perez emphasizes the kin relations that generate and sustain life:

"These are relationships of co-evolution and ecological dependency. [...] These

relationships produce the possibility of both life and any given way of life" (van

Dooren 4). In other words, his poemodel recalls the importance of recognizing

our co-dependence and profound intimacy with our non-human kin. In recognizing

our rich entwinement with the web of life, Perez's graph also battles the

perception that non-human animals are isolated "objects" for scientific

analysis; and he destabilizes the tendency to understand species loss from a

narrow, detached, statistical framework. The viewpoint presented by Perez's

graph thus resonates with Sophie Chao and Dion Enari's observation that climate

imaginaries from Indigenous communities in the Pacific "have always recognised

the interdependencies of human and other-than-human beings" and it pushes us

toward the "recognition that other beings, too, have rich and meaningful lifeworlds"

(35, 38). This is a crucial recognition for surviving

the Anthropocene, a time when the biocultural webs of life are being damaged

and undone on a scale that has never been witnessed.

By

dropping letters from the title, Perez's poem also gestures toward the broader

losses in knowledge and understanding that accompany species extinction.[2]

As Ursula Heise explains, animal extinction often functions as a "proxy" for

the profound, surprising, and often intangible disappearances that accompany

the loss of a species (23). This is due, in part, to the fact that species

occupy crucial positions in our cultural and imaginative structures—when

they disappear, the vital imaginative structures built around them are

unraveled and eroded. Think, for instance, of the ways in which the death of

coral reefs triggers anxieties over the disappearance of nature's beauty, of

possible medical discoveries, and of crucial habitats for a stunning range of

marine life.[3]

Recognizing this allows us to more fully register the unexpected effects of

species loss, and in turn, develop appropriate strategies for species

preservation. Moreover, by dropping letters from these important reference

points, we are pushed to more deeply and carefully engage with the information

that is being presented to us—our gaze must linger on the graph in order

to decipher and interpret its meaning.[4]

Through this slowed down, dialectical interaction,

fresh insights and understandings about the climate crisis can surface. Graphs

like this one, Heather Houser explains, thus illustrate how new ways of

thinking become possible when art

speaks back to forms of epistemological mastery" (1-2). And without new ways of

thinking, new relations may not be possible.

Perez's poemodel thus calls to mind Sophie

Chao and Dion Enari's description of climate imaginaries, which are "spaces of

possibility" and "ontological, epistemological and methodological openings for

(re)imagining and (re)connecting with increasingly vulnerable places, species,

and relations" (34). Climate imaginaries issue necessary calls for collective

action that are driven by ethical, material, and political prerogatives, while

simultaneously offering profound visions for inhabiting the world otherwise. In

doing so, they demand a decolonial approach to the Anthropocene and emphasize

the absolute importance of recognizing Indigenous cosmologies, philosophies,

and environmental knowledges.

The

essays that follow offer inspiring engagements with Indigenous climate imaginaries.

We begin with Conrad Scott's "'Changing Landscapes': Ecocritical Dystopianism

in Contemporary Indigenous SF Literature." In this essay, Scott develops

the term "ecocritical dystopia." In Scott's formulation, ecocritical dystopias

diverge from more traditional dystopian fiction through their unique engagement

with setting. Rather than imagine a future (even a near future) crisis to come,

ecocritical dystopias are anchored in the real world, bringing us closer

to crises that are already unfolding. As Scott puts it, "we are, after all,

connected to stories through our relationships (however tenuous) with the

real-world landscapes altered within the narratives." Scott develops this

sub-genre of dystopian fiction through an analysis of Harold Johnson's Corvus

(2015) and Louise Erdrich's Future Home of the Living God (2017), arguing

that these texts depict societies extrapolated directly from the present,

reminding us of the threat of environmental collapse.

Svetlana Seibel's "'Fleshy Stories': Towards Restorative Narrative

Practices in Salmon Literature" introduces an archive of fiction from the

Pacific Northwest focused on salmon—one

of the most significant cultural symbols of the region. These "salmon stories"

are organized around the "cultural and ecological significance of the fish

for Indigenous nations," and they highlight the pervasive reach of the

Anthropocene, which has materialized in numerous consequences for human-salmon

interdependencies and kinship. Inspired by Todd and Davis's observation that

"fleshy philosophies and fleshy bodies are precisely the stakes of the

Anthropocene," Seibel examines how salmon stories create textualities

of care aimed not only at criticizing the colonial economies, but at

narratively restoring the threatened lifeworlds of both the people and the

fish." Seibel reaches this conclusion through a powerful reading of Diane

Jacobson's My Life with the Salmon and Theresa May's Salmon is

Everything.

"Healing

the Impaired Land: Water, Traditional Knowledge, and the Anthropocene in the

Poetry of Gwen Westerman" by Joanna Ziarkowska reads the work of Sisseton

Wahpeton Oyate poet Gwen Westerman from the perspective of environmental

humanities and disability studies. The essay draws on Sunaura Taylor's understanding that the

use of "impaired" as a modifier demonstrates the extent to which Western

preoccupation with and privileging of ableism—able bodies which are

productive under capitalism—has saturated thinking about damaged

environments. Through Westerman's poetry, Ziarkowska locates Indigenous

survival in the preservation of traditions and attention to/care for the

land that is polluted, altered, and in pain. She argues that, in Westerman's

work, "'impairment' is an invitation to care and a construction (or rather the

preservation) of a relationship with the land and its human, non-human and

inanimate beings."

Emma Barnes situates her essay, "Women, Water and Wisdom: Mana Wahine in Mary Kawena Pukui's Hawaiian

Mo'olelo" within recent conversations surrounding how the Anthropocene

inaccurately unifies humans in their environmentally destructive behaviors and

in their experiences of climate change, and overlooks the fact that the unequal

effects of climate change disproportionately alter the lives of Indigenous

peoples. Barnes provides a literary analysis of two short stories

published consecutively by native Hawaiian writer Mary Kawena Pukui in her

collection Hawai'i Island Legends: Pīkoi, Pele and Others. Barnes

situates two narratives—"The

Pounded Water of Kekela" and "Woman-of-the-Fire and Woman-of-the-Water"—as climate change fiction, and argues that they depict

how drought and famine disproportionately affect Native women due to their

cultural and social roles. Through her analysis, Barnes highlights "the

resilience of native Hawaiian women in responding to a changing environment,

and to demonstrate the sacrifices Indigenous women make in their role as

cultural bearers."

"The Crisis in Metaphors: Climate Vocabularies in Adivasi

Literatures" by Ananya Mishra examines the role of Adivasi voices in climate

change discourse and literary studies. While Adivasis are the perpetual

subaltern in postcolonial studies, their voices offer a necessary critique of

the global industrial complex, one that echoes calls for sovereignty issued by

other Indigenous communities globally. Mishra unpacks this claim through an

examination of Adivasi songs emerging from the particular geography of southern

Odisha. In particular, she focuses on the usage of metaphors within early

climate change discourse: "Indigenous literatures hold early warnings of the

climate crisis in metaphors we do not yet center in climate discourse." These

metaphors, Mishra suggests, serve as archives of interpretations of the climate

crisis as already confronted by Indigenous communities within India.

Our final article, "Educating for Indigenous

Futurities: Applying Collective Continuance Theory in Teacher Preparation

Education" by Stephany RunningHawk Johnson and Michelle Jacob positions

climate change conversations within the classroom. Drawing on their experiences

as Indigenous university teachers, and from the experiences of their students

who are training to become elementary and secondary classroom educators, RunningHawk

Johnson and Jacob demonstrate how K-12 classrooms are vital sites for

anti-colonial and Indigenous critiques of the settler-nation, neoliberalism,

and globalization, all of which undermine Indigenous futurities while

simultaneously fueling climate change. Their goal, they explain, is to "frame

education as part of the larger project in which we can better understand our

ancestral Indigenous teachings for the purpose of deepening our Indigenous

identities and knowledges." This entails calling upon Indigenous peoples to

work as teachers and leaders within educational contexts, and urging

non-Indigenous allies to educate themselves on how they might best ensure

Indigenous resurgence, futurity, and "collective continuance."

Together, the contributions featured in this special issue remind

us that "stories frame our beliefs, understandings, and relationships with each

other and the world around us [...] our lives are interwoven stories [...] we live

in an ocean of stories" (Kabutaulaka 47). And through their engagement with

Indigenous storytelling, these essays posit new, vital directions for imagining

Indigenous climate justice in the Anthropocene. Rather than foreground

narratives of declension or demise in the context of anthropogenic climate

change, these essays underscore the importance of telling stories that center

self-determination, struggle, and solidarity. They emphasize, in other words,

the importance of maintaining that better worlds are not only necessary, but

possible. And in doing so, they open space for thinking and feeling our way

through—and potentially beyond—the colonial Anthropocene.