Speculative

Possibilities: Indigenous Futurity, Horror Fiction, and The Only Good Indians

NICOLE R. RIKARD

A

decade ago when Grace L. Dillon's Walking on the Clouds: An Anthology of

Indigenous Science Fiction was published, the term 'Indigenous futurisms'

began to describe the vast body of work that had already been and would

continue to be crafted by Indigenous storiers to create representations in

visions of futurity. The term pays homage to Mark Dery's coinage of

'Afrofuturism' in his work, "Black to the Future," from Flame Wars:

Discourse of Cyberculture (1993). In the 1990s, Dery sought to answer

urgent questions surrounding speculative fiction, including why so few African

American authors were composing in the genre, despite it being "seeming[ly]

uniquely suited to the concerns of African-American novelists" who are "in a

very real sense... the descendants of alien abductees" (179-180). Dery posed the

question, "Can a community whose past has been deliberately rubbed out, and

whose energies have subsequently been consumed by the search for legible traces

of history, imagine possible futures?" (180). Since Dery's inquiry, scholars

like Alondra Nelson, Ytasha L. Womack, and Greg Tate, just to name a few, have

contributed to the growing body of scholarship on Afrofuturism and the immense

possibilities it affords. It is not difficult to discern Dillon's

inspiration—Afrofuturism is a vital critical movement that continues to

influence Black activists, writers, musicians, filmmakers, scholars, artists,

designers, and more, and it seeks to create spaces and futures "void of white

supremacist thought and structure that violently oppress[es] Black communities"

and to "evaluat[e] the past and future to create better conditions for the

present generation of Black people through use of technology" (Crumpton par.

1).

A

decade ago when Grace L. Dillon's Walking on the Clouds: An Anthology of

Indigenous Science Fiction was published, the term 'Indigenous futurisms'

began to describe the vast body of work that had already been and would

continue to be crafted by Indigenous storiers to create representations in

visions of futurity. The term pays homage to Mark Dery's coinage of

'Afrofuturism' in his work, "Black to the Future," from Flame Wars:

Discourse of Cyberculture (1993). In the 1990s, Dery sought to answer

urgent questions surrounding speculative fiction, including why so few African

American authors were composing in the genre, despite it being "seeming[ly]

uniquely suited to the concerns of African-American novelists" who are "in a

very real sense... the descendants of alien abductees" (179-180). Dery posed the

question, "Can a community whose past has been deliberately rubbed out, and

whose energies have subsequently been consumed by the search for legible traces

of history, imagine possible futures?" (180). Since Dery's inquiry, scholars

like Alondra Nelson, Ytasha L. Womack, and Greg Tate, just to name a few, have

contributed to the growing body of scholarship on Afrofuturism and the immense

possibilities it affords. It is not difficult to discern Dillon's

inspiration—Afrofuturism is a vital critical movement that continues to

influence Black activists, writers, musicians, filmmakers, scholars, artists,

designers, and more, and it seeks to create spaces and futures "void of white

supremacist thought and structure that violently oppress[es] Black communities"

and to "evaluat[e] the past and future to create better conditions for the

present generation of Black people through use of technology" (Crumpton par.

1).

Indigenous

futurisms, like Afrofuturism, seek to explore the possibilities of alternate

pasts, presents, and futures by decentering Western perspectives. The

decentering of Western aesthetics and ideologies is essential and enables

Indigenous futurisms to "offer a vision of the world from an Indigenous (or

Native American) perspective," helping to address and explore difficult topics

like "conquest, colonialism, and imperialism; ideas about the frontier and

Manifest Destiny; about the role of women within a community; and about the

perception of time" (Fricke 109). As we continue to address and advocate for

change regarding the histories and atrocities of conquest, colonialism, and

imperialism worldwide, decentering the Western narrative of these

events—and therefore the narratives of how these events continue to

impact individuals and communities—is crucial.

Decolonizing

ideals and aesthetics is a theoretical and political process essential to decentering

Western-normative notions and, for Indigenous studies, recentering Indigenous

knowledges, cultural practices, and identities. Indigenous futurisms enable

Indigenous activists, authors, musicians, and more to decolonize the narratives

of the past, present, and future, and because the "Native American novel has

been experimental, attracting and modifying subgenres to seek Native cultural

survival and development... Native writers have made the novel their place of

both formal and social innovation" (Teuton 98). To qualify, I am not suggesting

that all Indigenous authors have or must use their works in the same

ways or to achieve the same goals; to do so would be a gross misstep and

extreme miscalculation of the literary and artistic possibilities afforded when

literature by individuals spanning 570+ federally recognized and unique Indigenous

tribal nations in the contiguous United States alone are often combined into

the category of Indigenous or Native American literature. Unfortunately,

though, there is often a misconception about these possibilities. As Indigenous

Literature scholar Billy J. Stratton states in a recorded interview with

Stephen Graham Jones, prolific novelist, short-story and essay-writer and

member of the Blackfeet Nation, "the notion of engaged readers and writers and

the recognition of good art has a strong bearing on Native literature because

it is not really allowed to be just entertainment. Gerald Vizenor has long been

advocating the production of literature as a function of what he calls

"surviv[ance], as a means to both persist and resist colonialism and its

legacy" (34). Jones responds:

When you're an American

Indian writer, it's like you have all this political burden put on

you—that you have to stand up for your people. You have to fight for

this, and you can't depict people this way or that way... my big goal, one of the

things I've been trying to do is to complicate the issue... (qtd. in Stratton

34)

The Only Good Indians (2020), a recent novel by Jones, exemplifies many strategies

and characteristics of Indigenous futurisms while also functioning as an

inventive work of horror fiction, a genre that has long been associated with

popular culture and stigmatized by literary studies' establishments. Jones is a

prolific author of many works of horror fiction including his most recent, Don't

Fear the Reaper (2023), The Babysitter Lives (2022), The Backbone

of the World (2022), "Attack of the 50 Foot Indian" (2021), "How to Break

into a Hotel Room" (2021), My Heart is a Chainsaw (2021), "Wait for the

Night" (2020), Night of the Mannequins (2020), and "The Guy with the

Name" (2020), and scholars like Billy J. Stratton, Rebecca Lush, Cathy Covell

Waegner, and John Gamber have contributed fruitful conversations concerning

Jones and his work. Similarly, scholarship on Indigenous futurisms continues to

grow, with artists, scholars, and authors like Lou Catherine Cornum (Navajo),

Suzanne Newman Fricke, Elizabeth LaPensée (Anishinaabe and Métis), Jason Lewis,

Darcie Little Badger (Lipan Apache), Danika Medak-Saltzman (Turtle Mountain

Chippewa), and Skawennati (Mohawk) cultivating the movement. This article seeks

to further both conversations—on Jones and The Only Good

Indians, as well as on Indigenous futurisms—by exploring the novel as

a work of Indigenous futurism, specifically as it relates to

rewriting the past, present, and future through various methods of Native

slipstream. Jones combines fictional newspaper headlines and articles, a

concentrated insistence on rationalization coupled with the inability to

achieve such measures, and various points of view in this novel. The result is

a depiction of resiliency and possibility for an alternative future in which

Indigenous worldviews replace the damaging cycles created and perpetuated by

Western ideologies. The Only Good Indians is an exceptional contribution

to the field of Indigenous futurisms, and it substantiates that both horror and

futuristic fiction can serve as an effective medium of decolonization.

a work of Indigenous futurism, specifically as it relates to

rewriting the past, present, and future through various methods of Native

slipstream. Jones combines fictional newspaper headlines and articles, a

concentrated insistence on rationalization coupled with the inability to

achieve such measures, and various points of view in this novel. The result is

a depiction of resiliency and possibility for an alternative future in which

Indigenous worldviews replace the damaging cycles created and perpetuated by

Western ideologies. The Only Good Indians is an exceptional contribution

to the field of Indigenous futurisms, and it substantiates that both horror and

futuristic fiction can serve as an effective medium of decolonization.

Science

Fiction, Horror, and Possibilities for Futurity

Indigenous

futurisms are largely prominent in the speculative fiction subgenres of science

fiction and fantasy, but they are certainly not mutually exclusive with these

genres; in previous work, I have illustrated how even

poetry is an effective and insightful genre being utilized by Indigenous poets

to reflect futurity (Rikard). Science fiction is the literary

genre that has received the most attention within the movement, though, and

this is due to several factors. First, like other subgenres of speculative

fiction, science fiction allows for considerable imagining with technology and worldbuilding.

In our innovative, technology-dependent contemporary moment, there is no

question that science fiction enables authors to bridge our everyday obsession

with and reliance upon technology with fictional world building. Additionally,

science fiction has always been and continues to be a medium of alternate

perceptions regarding our contemporary moment. In Scraps of the Untainted

Sky: Science Fiction, Utopia, and Dystopia (2000), Thomas Moylan acknowledges

that the genre is often misunderstood in two primary ways: many people

understand it as a medium for depicting an inevitable and undesirable future

caused by our contemporary flaws and damaging behaviors (usually classified as

'dystopian' or '(post)apocalyptic' fiction), or that it is simply a

metaphorical retelling of the present moment. Moylan argues that the purpose of

the genre is actually to "re-create the empirical present of its author and

implied readers as an "elsewhere," an alternative spacetime that is the

empirical moment but not that moment as it is ideologically produced by way of

everyday common sense" (5). For Indigenous futurists, science fiction is used

for more than just recreating the current moment in new spaces. Indigenous

futurists craft new futures and spaces for Indigenous lives and communities by

critiquing and modifying both the contemporary moment and the past. They illustrate

how Western knowledge systems and values control the present and how history

has been omitted and reconstructed to construe false narratives of Indigenous

histories and lives.

Given

considerably less attention than science fiction is how Indigenous storiers are

using the horror genre to explore Indigenous futurity, especially in literature

and literary studies. In recent decades, many works of horror have been

acknowledged as critical formations (literary and experimental horror) instead

of mere mediums of entertainment (genre horror), though the genre still

struggles for legitimacy in many literary spheres. Compare, for example, Toni

Morrison's 'L'iterary Beloved (1987), Mark Z. Danielewski's experimental

House of Leaves (2000), and Stephen King's highly popularized The

Shining (1977) and the ways in which these novels have been received by

popular culture and scholarly discourse. My intention is not to define literary

horror and/or genre horror or sort titles into these categories; this is a

fraught debate in literary circles that often leads to the blurring of lines

between the two forms and an overall dispute to be settled elsewhere. What I

argue, instead, is that genre horror fiction, literary or otherwise, often gets

overlooked as a well-suited method of exploring contemporary issues and

decolonizing Western modes of thinking and knowledge.

Horror

fiction has become seemingly easier to define over time, though as already

mentioned, it can be difficult to assess and agree upon which novels/stories

bend genre conventions and still function as part of the genre. Despite a few

misconceptions, horror fiction does not necessarily have to be concerned with

the supernatural, but "rather with forces, psychological, material, spiritual,

or scientific, that can be 'supernaturalized' and made into a force that

threatens the living with annihilation" (Herbert par. 1). Spanning centuries,

horror fiction has evolved to be categorized into two types of tales: those

determined by an external threat or force, either supernatural or logically

scientific, and those determined by an internal, psychological threat. There

are, of course, times when stories blend these two types of horrors, such as in

the case of The Only Good Indians. Whether internal or external threats

abound, horror fiction:

asks us to step back from

any straightforward historical realism and read at the very core of what

literature and the arts are about, that is, representation and interpretation,

the symbolic, and the use of strategies of estrangement and engagement to

explore and challenge cultural, social, psychological, and personal issues. (Wisker

404)

Horror

fiction, like other speculative fiction genres, allows for a revisioning of

recognized knowledge and the very Western normative ways in which this knowledge

has been enforced and proliferated. This work is not intending to claim that

Indigenous horror is new, but instead, that it is overlooked, especially within

the literary arts and scholarship in Indigenous studies. And, like Dillon, this

work advocates for the continuing use of horror fiction by Indigenous authors

and works to subvert Western notions of normalcy regarding knowledge, history,

time, and identity. As Blaire Topash-Caldwell

states:

Counter to

research on the negative effects of Native American stereotypes on youth,

positive representations of Native peoples observed in Indigenous SF portray

alternative futurisms to those represented in mainstream SF and celebrate Indigeneity

knowledge while making space for Indigenous agency in the future. (87)

As

the Indigenous futurisms movement continues,

Indigenous authors can use horror fiction to achieve similar possibilities

afforded by science fiction and Indigenous futurisms.

Indigenous

Horror and The Elk Head Woman

A

discussion about The Only Good Indians is not possible without

recognizing that the novel is a telling of the Elk Head Woman. Known by other Indigenous storiers as Deer Woman, Deer Lady, and

in Jones's novel, "Ponokaotokaanaakii," Elk Head Woman is a figure present in

many Indigenous tales across North America, including (but certainly not

limited to) those from the Muscogee, Cherokee, Anishinaabe, Haudenosaunee,

Choctaw, and Pawnee nations. These tales vary from one culture to another, but

according to Carolyn Dunn and Carol Comfort in Through the Eye of the Deer (1999),

"the traditional Deer Woman spirit... bewitches those who are susceptible to her

sexual favors and who can be enticed away from family and clan into misuse of

sexual energy" (xi). Though not always sexual in nature (Evers 41), these

stories are usually didactic and intended to warn youth of the consequences of

"losing social identity" through "promiscuity, excessive longing for one

person, adultery, and jealousy," ultimately underscoring their responsibilities

within the tribe (Rice 21, 28-29).

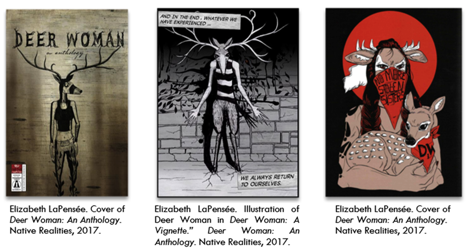

More

recently, Indigenous storiers have been revisioning Elk Head Woman to represent

female strength, sexual agency, and the fight for the thousands of Missing and

Murdered Indigenous Women across North America. Deer Woman: An Anthology (2017)

showcases various Indigenous authors' and artists' renderings of the figure.

Despite

the many variations of this figure in tellings and retellings, the blending of

the animal and human forms is consistent. This is unsurprising, because as Vine

Deloria Jr. states in God is Red (1973):

Very important in some of

the tribal religions is the idea that humans can change into animals and birds

and that other species can change into human beings. In this way species can

communicate and learn from each other. Some of these tribal ideas have been

classified as witchcraft by anthropologists, primarily because such

phenomena occurring within the Western tradition would naturally be interpreted

as evil and satanic. What Westerners miss is the rather logical implication of

the unity of life... Other living things are not regarded as insensitive species.

Rather they are 'people' in the same manner as the various tribes of human

beings are people... Equality is thus not simply a human attribute but a

recognition of the creatureness of all creation. (88-89)

Jones

adds to the revisioning of the Elk Head Woman in The Only Good Indians, depicting

Ponokaotokaanaakii as a figure seeking

retribution for a violent attack that took her life. Ten years before the novel

begins, the four narrators—Ricky, Lewis, Gabe, and Cass—decide to

break the rules of the

reservation and drive their truck through to the section preserved for elders,

where they come across a herd of nine elk. Lewis recounts that he "remember[s]

Cass standing behind his opened door, his rifle stabbed through the rolled-down

window... just shooting, and shooting, and shooting..." (62). Realizing that the

smallest elk (still just a calf) is still alive, they shoot her again—and

again after she still does not fall. The entire scene is horrific and haunts

the men for the rest of their short lives. The game warden finds the men

shortly after the slaughter and gives them an ultimatum: throw the entirety of

the meat down the hill and pay a high fine for breaking the rules of the

reservation or consent to never hunt on the reservation again. The men agree to

the second option, apart from entreating to take the body of the calf, which

Lewis silently swears to make complete use of so that her horrific death is not

in vain. The intended plan is successful for ten years—until Gabe throws

out a package of her meat that was stored in his father's freezer, initiating Ponokaotokaanaakii's vengeance.

Rewriting and Reclaiming

History and Narratives in The Only Good Indians

Native

Slipstream

Jones's

tale of the Elk Head Woman exemplifies many characteristics of Indigenous

futurisms. The Only Good Indians insists on rewriting histories, current

realities, and crafting a better future, and it does so by introducing elements

of what Dillon terms Native slipstream. This is an area of speculative

fiction that "infuses stories with time travel, alternative realities and multiverses,

and alternative histories" (3), a captivating tactic in Indigenous futurisms.

In Native slipstream, characters are seen as "living in the past, future, and

present simultaneously" (Cornum par. 2); time flows together, as Dillon notes,

"like currents in a navigable stream... [replicating] nonlinear thinking about

space-time" (3). In the first few narratives, the reader comes to understand

that its temporality is not stable or linear; it is distorted because of how

much the past influences the present, and ultimately the future, of each

character. In short, Jones utilizes narrative techniques to create temporal

distortion which allows him to jump around in the timeline of many years,

sometimes neatly and with elaborate transitions, and sometimes unexpectedly and

suddenly.

Native slipstream is not entirely synonymous with slipstream,

a term used to describe all speculative writing that simply defies neat categorization

and timelines. Coined by Bruce Sterling and Richard Dorsett in 1989:

slipstream is an attitude

of peculiar aggression against 'reality.' These are fantasies of a kind, but

not fantasies which are 'futuristic' or 'beyond the fields we know.' [Slipstream]

tend[s] to sarcastically tear at the structure of 'everyday life...' Quite

commonly these works don't make a lot of common sense, and what's more they

often somehow imply that nothing we know makes 'a lot of sense' and perhaps

even that nothing ever could... Slipstream tends, not to 'create' new worlds, but

to quote them, chop them up out of context, and turn them against themselves.

(78)

Native

slipstream in Indigenous futurisms is a way to reorient Indigenous ways of

thinking and assessing the world; it is the act of decolonizing time as a

linear, progressive model and understanding it as a myriad of possibilities.

This concept has been around since time immemorial and integrating it into

speculative literary genres such as horror and science fiction creates the

potential not to disorient the reader and create distrust in the timeline of

events, but to exemplify that Western ideology of time is arbitrarily

formulated and perpetuated. Indigenous storiers had been crafting slipstream

narratives far before a term was created to categorize it, with authors like

Gerald Vizenor (Anishinaabe), Sherman Alexie (Coeur d'Alene), Joseph Bruchac

(Abenaki), Louise Erdrich (Ojibwe), N. Scott Momaday (Kiowa), Leslie Marmon

Silko (Laguna Pueblo), and of course, Stephen Graham Jones (Piegan Blackfeet),

contributing.

In The Only Good Indians, Jones uses Native

slipstream to contradict 'official' narratives and the ways in which they are

retold, warping interpretations of time and events. He begins by integrating

extra-textual materials, specifically news headlines and articles. The reader

does not have to wait long to realize this will be a reoccurring and important

tactic, as the novel briskly opens with one such headline: "The headline for

Ricky Boss Ribs would be INDIAN MAN KILLED IN DISPUTE OUTSIDE BAR" (1). Then,

immediately following the headline, the narrator tells the reader, "That's one

way to say it" (1). In these first two sentences, Jones is outlining his

approach not only to use headlines to explain situations, but also his

insistence on using them to tell an important truth: no one, except the

person(s) living in the moment and experiencing the situation—and

sometimes not even then, completely—truly knows how situations unfold.

Throughout the novel, we realize these headlines are often

misconstrued, written by someone who has perceived the situation or would

potentially perceive it from a different angle without all

the details. For example, in Ricky's case, there is much more that happens

outside of the bar that night than a simple news article can explain. Ricky's

chapter is a short one, and the ending of the narrative sees Ricky witnessing

an elk running full speed in his direction, demolishing cars in the parking lot

outside the bar where Ricky stands. He seems to know that this must be some

sort of delusion or supernatural occurrence, reminding himself that "elk don't do

this" (8), but he nonetheless tries to flee from the terrifying animal.

Jones weaves perceived realities and delusions here, presenting Ricky as a

narrator who might not be the most reliable source for the truth of the

situation. Ricky remains self-aware, however, able to understand the bizarre

nature of what he is perceiving versus what other bystanders perceive. As the

men from inside and outside the bar move to the parking lot and see the damage

done to the cars, Ricky "saw it too, saw them seeing it: this Indian had

gotten hisself mistreated in the bar, didn't know who drove what, so he was

taking it out on every truck in the parking lot. Typical" (9). Jones employs

temporal distortion throughout this scene, leaving readers unsure whether what

Ricky is experiencing with the elk is real or a fabrication of his mind, and

this is left ambiguous as Ricky's story ends. (This reliability is examined in

more detail later.) After running as far as he can, Ricky sees "a great herd of

elk, waiting, blocking him in, and there was a great herd pressing in behind

him, too, a herd of men already on the blacktop themselves, their voices

rising, hands balled into fists, eyes flashing white" (12). Ricky realizes then

that he is not going to survive this encounter, and Jones integrates the news

headline that tells only part of the truth, here. This headline will forever

depict Ricky's futurity—whenever people speak of him or his death outside

that bar—as a different story from the reality he actually perceived and

experienced.

In

the next section of the novel, titled "The House Ran Red" and centering Lewis,

Jones more elaborately lays emphasis on the importance of perception. Most of

the headlines occur in this section; in fact, besides the headline on the first

page that has already been mentioned and the two full-length news articles

introduced later, this section introduces the only other extra-textual

materials, totaling ten headlines in all (16, 22, 36, 39, 45, 88, 121,

127) that compile Lewis's "mental newspaper" (16). He constantly rewrites his situations as they unfold in front

of him, giving each situation a headline that would break if anyone else were

to find out about his predicament. For example, when explaining why he and his wife

Peta will not have any children, the reader learns that Peta doesn't want her

children to have to "pay the tab" from the chemicals she put into her body

before she met Lewis (38). Lewis thinks to himself that, instead of the

headline reading, "FULLBLOOD TO DILUTE

BLOODLINE," like he initially thought it would when he married a white woman,

the headline would now read, "FULLBLOOD BETRAYS EVERY DEAD INDIAN BEFORE HIM"

(39). The truth of the matter is obviously more complex than a single-line

newspaper heading could ever convey. With these short newspaper headlines

seemingly redefining and limiting the scope of Lewis's everyday situations and

realities—and therefore his future (as he will be remembered by

others)—Jones is exemplifying the complexity of perception and how simple

the process of disseminating inaccurate realities and histories is. When

readers realize that Lewis's full name is Lewis A.

Clarke and he is the character mostly responsible for crafting these

inaccuracies, it becomes even more obvious that his narration is unreliable: a

nod to the many inaccuracies in Captain Meriwether Lewis and Lieutenant William

Clark's recording of their nineteenth century expedition.

As

mentioned, Jones also weaves two full-length news articles into the narrative.

One occurs at the end of Lewis's section, after he has brutally murdered a

co-worker named Shaney, who is also of Indigenous, Crow, identity, along with

his loving wife. The headline reads, "THREE DEAD, ONE INJURED IN MANHUNT"

(129). There are many inconsistencies in Lewis's and the newspaper reporter's

accounts, leaving the reader unsure whether to trust Lewis's narrative or the

article. Leading up to the news article, the third-person narrator reveals that

Lewis is found by four men with rifles; the news article reports that these men

were the ones to find Lewis are unconfirmed. It is then stated in the news

article that Lewis was apprehended by police, but later chapters reveal he was

actually killed. Lewis's chapter ends with him focusing on the elk calf before

being shot, though in his account it is unclear whether it is by the hunters or

someone else. Additionally, there is no mention of a teenage girl—the form Ponokaotokaanaakii

has taken on—though in the news article it suggests the men were attacked

by this teenage girl while Lewis and the calf were in the back of their moving

truck. Discrepancies such as these highlight how unreliable news articles can

be when reporting on complex situations, in addition to reflecting how

misinformation and lies are common in the creation of written history, or, as

termed by Gerald Vizenor in Manifest Manners (1999), the literature,

language, and narrative of dominance. Jones uses these 'official' articles, in

essence, to rewrite the characters' histories from a dominant ideological point

of view; everything must be rationalized through Western norms and presented to

the public in easily understandable ways, but often times, this information is

inaccurate. These news headlines and articles effectively integrate elements of

Native slipstream into the novel, as they outline the truth, or rather, the

lack thereof, about how histories are told and information is disseminated.

(Un)Reliability: The Splitting

of the Westernized Mind

Jones's

use of newspaper headlines positions the present as a space and time that also

exists in the future, as Lewis (presently) predicts how the situation will be

perceived by others (in the future). This usage also exemplifies how the past

can be recorded imperfectly due to incomplete information, differing perspectives,

and intentional falsehoods at play in colonial discourses. As such, Jones

challenges notions of Western, scientific thought. Lewis represents this

ideology and continually tries to rationalize events that unfold before him.

Everything in the novel is centered around that day in the clearing when they

killed the elk. These men cannot go back and erase what they have done in their

past, and consequently, Ponokaotokaanaakii returns to rewrite their present and

futures, reclaiming her own history she never had the chance to experience.

Ricky and Lewis spend most of their narratives thinking about this past that

cannot be undone, and Jones introduces elements of implausibility in each of

their stories. For example, Lewis continuously diminishes the abilities and

possibilities of Ponokaotokaanaakii, explaining

that the elk shouldn't have been able to conceive that young and at that

point in the hunting season; how even if she didn't encounter the hunters that

day, she couldn't have carried full term (73); that he couldn't have

seen her in his home (20), that she wouldn't even have fit in his living

room (37); that "of course and elk can't inhabit a person..." it had to

have been "a shadow he probably saw wrong" (82). Gabe also exemplifies this

type of perception where, if logic cannot explain it away, it cannot be true.

For example, when Gabe and Lewis are discussing the possibility that the elk

herd could remember them from that fateful day ten years ago, Gabe laughs it

off and tells him, "they're fucking elk, man. They don't really have campfires"

(27). And when Gabe is about to enter the sweat lodge with Cass and Nate, he

thinks he sees a glimpse of black hair in the mirror of Cass's truck, "[e]xcept

that couldn't have been" (195). Lewis, Gabe, Ricky, and Cass obsessively

rationalize their every encounter and almost always from a Western perspective,

trying to explain what could not and should not have been

possible, yet there are obviously things they are not able to explain or fully

rationalize. As such, an uneasy tension of unreliability builds between these

narrators and readers, challenging the latter to assess the truth with all of

the information available from the omniscient narration.

To

complicate this process, Jones weaves elements of internal and external threats

together throughout the novel, challenging the reader to decide if the real

antagonist in the novel is an external threat (Ponokaotokaanaakii) or internal ones (the men's

psychologies, internalized colonial ideologies, and emotional distress). This

is exemplified from beginning to end, with Ricky's narrative indicating that

there is indeed an elk responsible for the destruction of the vehicles outside

of the bar (as already explored); to Lewis's paranoia, ostensible unraveling,

and double homicide of Shaney and Peta; to Gabe's and Cass's gruesome

murder-suicide outside of the sweat lodge. Jones's masterful use of indirect

characterization—most fruitfully, each character's internal dialogue and

external dialogue with others—engages readers and challenges them to

determine the truth of the narratives. Toward the end of Lewis's section, this

type of characterization reveals that Lewis's mental state has deteriorated

significantly and his paranoia is controlling his emotions and actions. Leading

up to and after the murder of Shaney, his thoughts become jumbled and panicked,

filled with questions and desperate rationalizations for his thoughts and

actions:

She didn't know about the

books, he repeats in his head.

Meaning?

Meaning she was Elk Head

Woman.

Because?

Because she was lying.

That means she's a

monster?

...no, he finally admits to

himself. It doesn't mean for sure she's that monster, but added together

with the basketball being so alien to her, and her knowing where to stand in

the living room, and to turn the fan off, and, and: What about how she wouldn't

touch her own hide on the kitchen table?

Lewis stands nodding.

That, yeah.

She could have been

lying..." (118-119)

Lewis

can't stop himself from calculating the logic in his and Shaney's actions,

breaking it down to modus ponens (If A, then B; B; therefore A) and modus

tollens (If A, then B; not B; therefore not A) arguments. By the end, he

estimates that "[h]e's not even really a killer, since she wasn't even really a

person, right? She was just an elk he shot ten years ago Saturday. One who

didn't know she was already dead" (117-118). Lewis's paranoia engages a sort of

distortion where it is difficult for the reader to assess if he is losing his

ability to accurately assess and engage reality, or if there really is a

supernatural, external force manipulating him and the people around him and he

is beginning to see the world as it truly is—that is, from an

Indigenous worldview. His thoughts do become frantic, but in later chapters, it

is revealed that at least some of Lewis's assumptions and explanations are

true, such as when Gabe confirms that he did indeed throw out the elk

meat stored in his father's freezer.

In

Lewis's, Gabe's, and Ricky's chapters, they struggle with what is real and

what simply cannot be, and they use Western notions of regularity to do so.

When confronted with the unexplainable, their minds seem to crack down the

middle. One side confirms that it is indeed impossible for Ponokaotokaanaakii

to exist and be responsible, because Western notions of science cannot explain

such an entity and its reign on the real world. The other side reinforces

Blackfeet ideology, insisting on a clear, supernatural connection. Blackfeet

ideology has always emphasized strong ties with the supernatural and unique

ways of seeing the world in relation to it. William Farr asserts, "the

Blackfeet world possesse[s] an extra dimension, for amid the visible world,

[is] an invisible one, another magnitude, a spiritual one that is more

powerful, more meaningful, more lasting. It [is] a universe alive'" (qtd in

LaPier xxxi). The invisible dimension is, according to many Blackfeet histories

and stories, the real world—and the visible dimension is a mere partial

experience of that world (LaPier 25). If these characters' brains have indeed

split between Western and Blackfeet ideologies, the 'distortion' of sorts is a

battle of principles regarding the supernatural, space and time, and the

classification of the 'real.'

Indeed,

"this

confounding of divisions... between the animal and human—challenges western

ways of thinking" (Dunn and Comfort xiii); as such, Lewis, Gabe, Ricky, and

Cass cannot accept the events occurring around them as they exercise Western notions of science, nature,

and the perception of the Elk Head Woman. "While the non-Native cultural

product makes Deer Woman a monster, thus evincing the colonial(ist) impulse of

consuming the Indigenous... Native works... interpret Deer Woman as symbolic of the

Indigenous worldviews" (Vlaicu 3; Dunn and Comfort xiii). Jones exemplifies the unreliability of Lewis's,

Gabe's, Ricky's, and Cass's thoughts as they depend on limiting notions of

Western thought to try and understand the Blackfeet world around them. Western

ideologies simply cannot account for the strange circumstances that befall the

characters throughout the novel, insisting on a more traditional explanation

and one that allows a space for supernatural events. If we attempt to understand

the world using Blackfeet cosmology, what does Ponokaotokaanaakii truly

symbolize, as the partial experience of the real, invisible world?

Point

of View: Perspectives and the Construct of Time

Another

tactic Jones utilizes to build upon Native slipstream principles is point of

view. The novel begins in third-person narration following Ricky, then

Lewis—and then there is an abrupt shift in the point of view to second

person. In the second section, "Sweat Lodge Massacre," the

first chapter inserts readers into the mind of Ponokaotokaanaakii. The

narration reveals the elk's short life and horrendous death, outlining the

events of the day she was killed in her own perspective. In horror fiction, it

is unsurprising to see through the eyes of the antagonist. However, in Jones's

novel, this perspective shift occurs nearly halfway through the entire

novel, surprising readers with a fresh, new perspective on the incident that

took place ten years ago, the progression of time, and the deaths of the main

characters. Beginning in that second section, Jones begins weaving instances of

second person into Gabe's and Cass's chapters, reminding readers that there is

always more than one perspective of every situation. Ponokaotokaanaakii is

always watching and assessing these men, stalking them like prey to attain

vengeance. While Lewis becomes obsessed with figuring out why, ten years later Ponokaotokaanaakii

has chosen to come after them, she asserts, "for them, ten years ago, that's

another lifetime. For [Ponokaotokaanaakii] it's yesterday" (137).

Additionally, the ways in which Ponokaotokaanaakii transforms illustrates that

she is beyond the understanding of Western notions of time. She recounts:

Just a few hours ago you [Ponokaotokaanaakii]

are pretty sure you were what would have been called twelve. An hour before

that you were an elk calf being cradled by a killer, running for the

reservation, before that you were just an awareness spread out through the

herd, memory cycling from brown body to brown body, there in every flick of the

tail, every snort, every long probing glared down a grassy slope. (134)

The

way in which Ponokaotokaanaakii perceives time indicates

that time is an arbitrary construct, at least as the four men perceive

it—indeed, the entire construction of time as a linear ideal is deconstructed

as their views on time are juxtaposed. In interviews, Jones has described

himself as a "Blackfeet physicist," creating timelines that reflect "a

Blackfoot framework of loops, glitches, and the constant experience of

Indigenous time travel: living in the past, future, and the present simultaneously"

(Cornum qtd. in Fricke 118). This is exemplified throughout the novel with the

revisioning of the past, present, and the future (with news headlines and

articles); the merging of past and present with each character hyperfixated on

that fateful Saturday ten years gone, which ultimately defines their futures;

and the past and present becoming intertwined as dead characters interact with

those that are still alive—Ponokaotokaanaakii throughout, and Ricky and

Lewis in the sweat lodge. These revisionings fashion space and time as

interconnected and non-linear, a direct contradiction to notions of Western

knowledge regarding time. Such a pushback against dominant modes of thinking

offers an alternative reorientation of Indigenous knowledge and perception.

Decentering Western Ideologies and Crafting Indigenous

Futurity

Ultimately,

Denorah, Gabe's daughter, ends the destructive, murderous cycle that has

defined and controlled the lives of her father, Lewis, Cass, Ricky, Ponokaotokaanaakii, and more symbolically, everyone controlled by

Western perceptions of knowledge, history, time, and identity that has been

engrossed in this same cycle. Although it might appear that this cycle began

with the slaughtering of those elk in the clearing ten years ago, it is indeed

more complex. Lewis clarifies this when he reflects:

That craziness, that heat of the moment, the

blood in his temples, the smoke in the air, it was like—he hates himself

the most for this—it was probably what it was like a century or more ago,

when soldiers gathered up on ridges above Blackfeet encampments to turn the

cranks on their big guns, terraform this new land for their occupation.

Fertilize it with blood. (75)

Lewis

explains that he has contributed to a centuries-old cycle with the slaughtering

of those elk—one that continues to control him and others because of the

hands they continue to play within it. However, Denorah

refuses to let the destruction of the past define her present and future, and

she takes a courageous stand,

ending the long cycle of murder and retribution. Denorah chooses a new path

where she, Ponokaotokaanaakii, and everyone else can move on from the

atrocities of the past into a new future of possibilities. In this way, Denorah

represents and practices an Indigenous worldview. She accepts

Ponokaotokaanaakii's existence and, by doing so, the possibilities for a

better, alternative future for her generations and the ones to follow, which is

illuminated in the final lines of the novel: "It's not the end of the trail,

the headlines will all say, it never was the end of the trail. It's the

beginning" (305).

Stephen Graham Jones's The Only Good Indians is a

powerful and timely contribution to the Indigenous futurisms movement. Jones

experiments with various forms of Native slipstream tactics, weaving a

narrative that attempts to rewrite the past, resituate the present, and create

possibilities for the future. Newspaper headlines and articles, an intense

focus on rationalization coupled with the inability to achieve such measures,

and varying points of view combine to illustrate futurity and possibilities

created by breaking the cycle of Western perceptions and dominant ideologies.

According to Danika Medak-Saltzman, Indigenous futurist imaginings "create

blueprints of the possible and [provide] a place where we can explore the

potential pitfalls of certain paths," enabling us to "transcend the confines of

time and accepted "truths"—so often hegemonically configured

and reinforced—that effectively limit what we can see and experience as

possible in the present, let alone imagine into the future" (143). With The

Only Good Indians, Jones uses the horror genre to decenter dominant

ideologies and to offer potential futures in which Indigenous knowledge systems

and practices are centered in Indigenous lives. As Sean Teuton posits, "[t]he Native American novel has become

increasingly aware of itself as an art with real world consequences for Native

lives" (99), and further, The Only Good Indians and other fiction by

Jones supports horror fiction, specifically, as an effective medium for

subverting Western notions of normalcy regarding knowledge, history, time, and

identity. As the

Indigenous futurisms movement continues to develop and Indigenous creators

continue crafting new spaces and possibilities for representing Indigeneity,

scholarship must recognize and address how horror fiction is being used to imbue

Native sensibilities and knowledge.

Works Cited

Cornum,

Lindsey Catherine. "The Creation Story Is a Spaceship: Indigenous Futurism and

Decolonial Deep Space." Voz-à-Voz, 2018.

www.vozavoz.ca/feature/lindsay-catherine-cornum.

Crumpton,

Taylor. "Afrofuturism Has Always Looked Forward." Architectural Digest, 2020.

www.architecturaldigest.com/story/what-is-afrofuturism.

Deloria, Jr., Vine. God Is Red:A Native View of Religion. New York: Fulcrum Publishing, 2003.

https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uark-ebooks/detail.action?docID=478520.

Dery,

Mark. "Black to the Future: Interviews with Samuel R. Delaney, Greg Tate, and

Tricia Rose." Flame Wars: Discourse of Cyberculture, edited by Mark

Dery, Durham: Duke UP, 1994, 179-222.

Dillon,

Grace L. Walking the Clouds: An Anthology of Indigenous Science Fiction. Tucson:

U of Arizona P, 2012.

Dunn,

Carolyn and Carol Comfort. Introduction. Through the Eye of the Deer: An

Anthology of Native American Woman Writers. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books,

1999.

Elliot,

Alicia. "The Rise of Indigenous Horror: How a Fiction Genre Is Confronting a

Monstrous Reality." CBC/Radio Canada, 2019.

www.cbc.ca/arts/the-rise-of-indigenous-horror-how-a-fiction-genre-is-confronting-a-monstrous-reality-1.5323428.

Evers,

Larry. "Notes on Deer Woman." Indiana Folklore 1.11, 1978: 35-45.

Fricke,

Suzanne Newman. "Introduction: Indigenous Futurisms in the Hyperpresent Now." World

Art 9.2, 2019: 107-121. doi: 10.1080/21500894.2019.1627674.

Gelder,

Ken. "Global/Postcolonial Horror: Introduction." Postcolonial Studies

3.1, 2000: 35-38. doi:10.1080/13688790050001327.

Graham

Jones, Stephen. The Only Good Indians. New York: Saga Press,

2020.

Herbert,

Rosemary. "Horror Fiction." The Oxford Companion to Crime and

Mystery Writing. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2005.

https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195072396.001.0001/acref-9780195072396-e-0324.

Higgins,

David M. "Survivance in Indigenous Science Fictions: Vizenor, Silko,

Glancy, and the Rejection of Imperial Victimry." Extrapolation

57.1, 2016: 51-72. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3828/extr.2016.5.

Lapensée,

Elizabeth. Deer Woman: An Anthology. Albuquerque: Native Realities, 2017.

LaPier,

Rosalyn R. Invisible Reality: Storytellers, Storytakers, and the

Supernatural World of the Blackfeet. Lincoln: U of Nebraska P, 2017. doi:

https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1s475jg.

Medak-Saltzman,

Danika. "Coming to You from the Indigenous Future: Native Women,

Speculative Film Shorts, and the Art of the Possible." Studies in

American Indian Literatures 29.1, 2017: 139-171. muse.jhu.edu/article/659895.

Moylan,

Tom. Scraps of the Untainted Sky: Science

Fiction, Utopia, Dystopia. Boulder: Westview Press, 2000.

Rice,

Julian. Deer Women and Elk Men: The Lakota Narratives of Ella Deloria. Albuquerque:

U of New Mexico P, 1992.

Rikard,

Nicole. "The Craft of Rewriting

and Reclaiming: Indigenous Futurism in Postcolonial Love Poem and The

Only Good Indians." University of Arkansas (2021): student paper.

Roanhorse,

Rebecca et al. "Decolonizing Science Fiction and Imagining Futures: An

Indigenous Futurisms Roundtable." Strange Horizons, 2017.

http://strangehorizons.com/non-fiction/articles/decolonizing-science-fiction-and-imagining-futures-an-indigenous-futurisms-roundtable/.

Sterling,

Bruce. "Slipstream." Science Fiction Eye 1.5, July 1989: 77-80.

Stratton,

Billy J. The Fictions of Stephen Graham Jones: a Critical Companion. Albuquerque:

U of New Mexico P, 2016.

Teuton,

Sean. Native American Literature: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford:

Oxford UP, 2018.

Topash-Caldwell,

Blaire. "'Beam Us up, Bgwëthnėnė!' Indigenizing Science (Fiction)." AlterNative:

An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples 16.2, 2020: 81–89.

doi:10.1177/1177180120917479.

Vizenor, Gerald. Manifest Manners. U

of Nebraska P, 1999.

---. "The Ruins of Representation: Shadow Survivance

and the Literature of Dominance." American Indian Quarterly, 17.1,

1993: 7–30. https://doi.org/10.2307/1184777.

Wisker,

Gina. "Crossing Liminal Spaces: Teaching the Postcolonial Gothic." Pedagogy

7.3, 2007: 401-425. muse.jhu.edu/article/222149.