RESEARCH ARTICLE

“Awasi-: Visual Images In Works From Kimberly Blaeser, Louise Erdrich, And Gerald Vizenor”

CHRIS LALONDE

Our aim is to shed light on the relationship between visual representations and kinship, connection, and worldview present in work by three Indigenous literary artists: White Earth Anishinaabe band members Kimberly Blaeser and Gerald Vizenor and Turtle Mountain Chippewa [Anishinaabe] Louise Erdrich. All three deploy words in multiple genres articulating another way of knowing and being rooted in Anishinaabe worldview, culture, and history. Small wonder then that they also deploy Anishinaabemowin, the language of the people, in their works.[1] Blaeser's photographs in her 2019 volume of poetry Copper Yearning and elsewhere, Erdrich's drawings in her memoir Books and Islands in Ojibwe Country (2003), and Vizenor's photographs in his mixed-genre The People Named the Chippewa (1984) complement and reinforce their words, and vice-versa. Building on Vizenor's thinking regarding fugitive poses, Blaeser notes that "photographs have the ability to bend and refract dominant stories" ("Refraction and Helio-tropes"184). Drawings done by Indigenous artists can do the same. Explicitly signaling liberation from the damning representations created by non-Indigenous visual and literary artists, as Blaeser does, indicates how high the stakes are for her, Vizenor, and Erdrich, for the Anishinaabeg, for all Native American and First Nations peoples. We would do well to look first at two telling photographs, each anchoring a revealing newspaper article published on June 30, 1936 in order to see what is at issue and at stake.

Picture, then, this: after a quick glance at the front page of the day's Minneapolis Tribune a reader cracks open the paper to its centerfold and, schooled to read left to right and tending to be drawn to images, the eye lights on a head-and-shoulder photograph of Frances Densmore accompanying a five-page article announcing that the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) would be hosting a luncheon that day in her honor. [fig. 1]. Born in Red Wing, Minnesota and educated at the Oberlin College Conservatory of music, Densmore was by 1936 a well-established and accomplished fieldworker and ethnographer, or what we now term an ethnomusicologist, known for her collection and study of Native American music and songs from a host of different Indigenous nations as well as for her work on Native American customs and cultures more generally.

Over across the centerfold is a headshot anchoring another five-paragraph article. This photo is of Clement Vizenor, whose murder was front-page news the day before in the three major Minneapolis dailies of the time, including the Tribune. [fig. 1] The front-page coverage of the slaying was pretty much the same, although the Minneapolis Star saw fit to sensationalize the murder to a greater degree. Each paper highlighted the violent nature of the killing, its location, and the death of Vizenor’s brother Truman early in the month; each gave Clement’s age and occupation, and noted, variously, that he was “part Indian,” “quarter Indian,” “a half-breed.” He hailed from White Earth. Gerald Vizenor is his son.

Two photographs across from each other on 30 June: one, a formal studio portrait; the other, a smiling snapshot; one a noted scholar; the other, victim. Two articles of roughly the same length, articles that could not be more different: one containing a recognition and celebration of a person's body of work to date; the other, offering questions without answer and the silence that comes with death. That silence resounded twenty-five years later when Gerald Vizenor sought answers concerning the murder and subsequent investigation. The murder unsolved, it resounds still today.

Fig 1

The five-paragraph article devoted to the DAR's honoring tea for Densmore notes that she was fresh from fieldwork in northern Minnesota, up around Cass Lake, and that Chippewa arts and crafts she had collected were on display in a monthlong exhibit at the Walker Art Gallery in Minneapolis that had opened the previous day. Although the Tribune did not cover the opening, its article on the 30th did include the title of Densmore's address: "The Influence of Nature on Chippewa Art." The topic had occupied Densmore for at least a decade—she published Chippewa Customs in 1927—and would continue to do so after 1936.

Densmore's 1936 gallery talk seems never to have been published, but the Minnesota Archaeological Society included in its August 1936 Bulletin a summary of a talk on the handicraft and art of the Chippewa that Densmore gave to the society, headquartered in a lower floor of the Walker Gallery at that time. It is unclear if the Archaeological Society talk and the exhibition opening address were one and the same, although it is plausible given that they share the same subject, but either way, the 1936 summary and an address from her in 1941 entitled “The Native Art of the Chippewa” make clear Densmore's assertion that Chippewa art either imitates or interprets nature. Whether Chippewa art was initially imitative and then interpretative or vice versa, and therein lies the contradiction between the two addresses, Densmore holds that the art was in decline: the 1936 account notes “This state was when the Indians had too many beads, etc. to work with and was the beginning of the downfall of Indian Art” (1). This is consistent with her position in Chippewa Customs. There she writes,

It appears that in the development of Chippewa design an interpretation of nature through conventional flower and leaf forms preceded an imitation of nature. It appears further that the spirit of real art decreased as the imitation of nature increased until the floral patterns in use among the Chippewa of to-day have no artistic value. (Chippewa Customs 186)

While Densmore holds that the early patterns were marked by their veracity, she stated that “the chief characteristic of modern Chippewa art is its lack of truth and its freedom of expression” (Chippewa Custom 189). This, for Densmore, marked the art’s decline.

More than a decade later, the conclusion of the 1941 address is especially damning:

The native art of the Chippewa cannot be “revived,” for it was part of the

life of the wigwam—the old life of simple pleasure and clear thinking.

The birchtrees still stand on the hillsides but the native art of the Chippewa is gone forever. (681)

For Densmore, then, while the natural world remains, Anishinaabe art connected to nature has vanished. While not often a wordsmith, to my ear at least, with double vowels and consonants, with soft endings, most tellingly for all save “stand,” and “art,” Densmore’s closing move tacitly asks, and answers, can the indian, to deploy Vizenor's term capturing the construction created and perpetuated by the settler-colonial society, be far behind?

Densmore implicitly asked and explicitly answered what was for her and others that rhetorical question well before 1941. Her 1915 "The Study of Indian Music" concludes both by stating that "the songs of a vanishing race must be preserved" and that the "Indian" would be better understood through a study of the music. Then in her enumeration of the four reasons for studying "Indian music" an astonishing emplacement: "Too much has been said and written about the tragedy of the vanishing race. We need to be reminded that the Indians were a race of warriors and knew how to face defeat. There was no self-pity in the heart of the Indian and he asked no pity from others" (197). Here Densmore admonishes her readers to cease dwelling on the tragedy of the vanishing indian because the indians recognize and accept that they have been defeated. Thus cleared from having to bring up the "tragedy" and in doing so cleared from at the very least acknowledging the role played by the dominant settler-colonial society, Densmore and her readers can now rest easy with the claim that the vanquished "deserve to be honored" and that she and they do them that honor by accepting, and studying, the gift of their music, a cherished possession that "Today they are willing to give to us" (197). Thirty years later, Densmore calls on her readers to find "old Indians," take them to town, and record them singing their songs "before the opportunity is gone" for "Nothing is lost so irrevocably as the sound of song, and among the Indians, as with many other peoples, music was an important phase of native culture" ("The Importance of Recording Indian Songs" 639).[2]

That same dying fall is captured in the Minnesota Archaeological Society's summary of Densmore's 1936 talk and, according to the Society, her emphasis on "the beginning of the downfall of Indian Art." It should come as no surprise, then, that the June 30,1936 Tribune article devoted to the murder of Clement Vizenor across the way from the piece on Densmore closes on a dying fall as well when it notes that Clement’s brother Truman met “a violent death” falling from a railway bridge at the beginning of the month. The article offers a trace of the natural world, noting that Truman’s “body was found in the Mississippi River.” Still, rather than undoing the same old story of death, of the always already absent fervently wished for by the dominant society, the Tribune update, like Densmore's readings of nature and Anishinaabe art, reinforces it.

Two photographs, then, two still images: the subject of each in its own way connected to the same old indian story, one told and retold in words and pictures as the cornerstone of the national narrative of the nation and the dominant settler-colonial society. It is fitting rather than fortuitous happenstance that the photograph of Clement Vizenor is across the sheet of Tribune newsprint from the photograph of Frances Densmore, for by 1936 Densmore had been taking photographs as part of her fieldwork for nearly thirty years. In fact, her first professional fieldwork in 1907 included both songs and a revealing photograph of Flat Mouth, hereditary head of the Pillager band of the Anishinaabe, taken a day after his passing at Onigum on the Leech Lake reservation east of the White Earth reservation. Densmore had arrived at Leech Lake as members of the Midewiwin, or Grand Medicine, Society were ministering to the elder and she looked on as they attempted to heal him with medicine, chant, and song. The day after Flat Mouth's death, Densmore was given permission to photograph his body. Her report to the Smithsonian Institution's Bureau of Ethnology (BAE) of what she had heard and seen at the two reservations helped her to secure her accompanying request for funding. With equipment purchased with some of the one hundred and fifty dollars she received, Densmore traveled north again in September to record Anishinaabe songs and music.

It is fitting that Densmore captured Flat Mouth in state with her camera, for, as she had written to the BAE when requesting funding, she desired "to record Indian customs before they disappeared forever" (Archabal 101). What better way to drive home that point, drive home the urgency, than with Flat Mouth's corpse. Once again, the indian is consigned to a narrative of inevitable loss. While the image is revealing, it tells only a part of the story of what Densmore appears to have desired concerning her photographing of indians. Equally revealing is a story Densmore recounts in her papers of photographs she did not take. In his essay on Densmore's photographs of Natives in Minnesota, Bruce White notes that Densmore longed to take pictures of her indian subjects without their knowledge; she wrote, "I had been inspired by tales of taking pictures unbeknownst to primitive people and thought I would try it" (qtd. in White 321). Her phrasing is telling, with "primitive" locating the indian on one side of the uncivilized-civilized binary and "unbeknownst" locating Densmore and her profession on the other.

Densmore's description of her sole effort to photograph indians in such a way replicates the binary:

With my camera I went to an Indian ceremony that was to take place in an enclosure surrounded by a high board fence. There were knotholes in the fence and I thought it would be a good stunt to stand outside the fence and take photographs through a knothole. Having established myself in location I was ready for a fine afternoon, until an Indian found me. It is not necessary to tell what followed, but I never tried to take pictures in that way again.

(qtd. in White 321)

The barrier is as much figurative as literal—indians on one side, anthropologists on the other—for as White points out, Densmore, as was true of her contemporary anthropologists, was interested in the indian of and in the past, "showing little interest in the complete contemporary lives of her subjects" (White 341). No wonder, then, that it was "not necessary to tell what followed," for to have done so would have meant giving voice to the native, their thinking, and likely their emotional response to yet another member of the dominant society coming to take something vital to the people. For all Densmore's commitment to indian song and singing, here the native must be silent.

In Fugitive Poses: Native American Indian Scenes of Absence and Presence Vizenor invokes silence as well, but in the name of resistance, writing,

Natives posed in silence at the obscure borders of the camera, fugitive poses that were secured as ethnographic evidence and mounted in museums. That silence could have been resistance to the mummers of camera dominance. Eternal poses are not without humor, but the photographic representations became the evidence of a vanishing race, the assurance of dominance and victimry" (155).

Against the emplacement constructed for the indian, native artists create moving images that go beyond the rupture, cleaving, and deracination produced and perpetuated by the dominant society: in Anishinaabemowin the word is awasi- (a preverb): beyond, over across.

There is more than a trace, more than an inkling, of Vizenor's transmotion in the deployment of awasi-, for both prefix and preverb signal movement, a change of position, going beyond. We need only go to Vizenor's "The Unmissable: Transmotion in Native Stories and Literature" in the inaugural issue of Transmotion to register that native transmotion, the "visionary or creative perception of the seasons and the visual scenes of motion in art and literature,” is "directly related to the ordinary practices of survivance, a visionary resistance and sense of natural motion over [the] separatism, literary denouement, and cultural victimry" we see at work in Densmore's thinking and images (69, 65).

In an essay on Indigenous photography, including her own work, White Earth Anishinaabe writer, scholar, and photographer Kimberly Blaeser writes of finding in her "Indigenous Indices of Refraction, Brussels 2012" what Vizenor terms “an elusive native [not indian] presence” (Fugitive Poses 156): her image as she triggers the shutter. [fig. 2] For Blaeser, “Out from that noticing [Indigenous] eye and tiny instrument of aperture and mirror opens the entire scene—an interactive image of refracted light, shadows, and imaginative connections” (“Refraction and Helio-tropes” 184). As is true of the “actual family images” (Native Liberty 165) invoked by Vizenor that go beyond the painfully easy simulations of absence that are indian images, going beyond thanks to the native stories connected to them, Blaeser’s “Indigenous Indices of Refraction, Brussels 2012” goes beyond the stereotypes created and perpetuated by the dominant society thanks to the “imaginative connections” that Blaeser identifies. The photograph is an example of what Blaeser labors to create: in her words, “my own photographs or picto-poems aspire to create or invoke a kind of cultural or transcendent nexus of connections, regardless of the subject. They enact a process of sometimes unexpected associative links” (“Refraction and Helio-tropes” 183). What holds for “Indigenous Indices of Refraction, Brussels 2012” holds for more than that creation or even the rest of her oeuvre, as Blaeser knows and makes clear by noting in her essay's conclusion, “Working amid a complex history and hive of Indian images, Native photographers choose various paths to liberate Native representation, offering new slants or angles of sight, casting cultural light, inviting vision beyond the frame” (“Refraction and Helio-tropes” 188; emphasis added).[3]

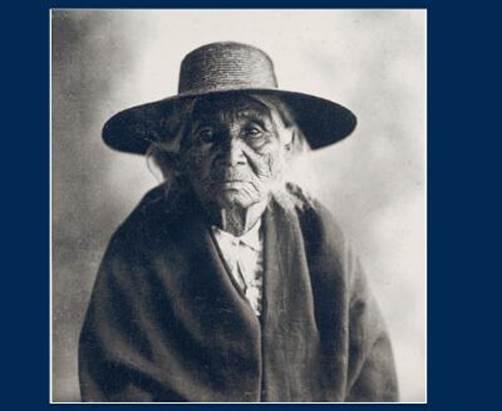

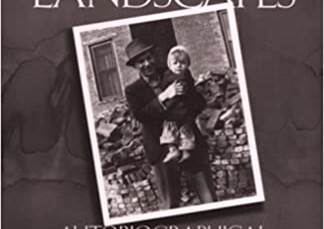

At a glance, both the first and the last photograph in Vizenor's The People Named the Chippewa might seem to consign the native to death. The cover photo of the paperback edition is followed by The People Named the Chippewa standing alone on the first page seen upon opening the book. [fig. 3]

Fig. 3

A turn of that page reveals the same photographic image as frontispiece, over across from which is the full title page, including the text's subtitle, the name of the author, the publisher, and place(s) of publication. Crucially, then, the design of the book emphasizes title as well as image, priming us to see a gap opening between the Anishinaabe and the dominant culture's positioning of them in the latter's terms—the people named the Chippewa (emphasis added)—a positioning that here and throughout his career Vizenor has taken pains to both point out and undo.

We see and then see again the image of an Anishinaabe adult woman of indeterminate age with weathered and wrinkled facial skin, slumped shoulders, her upper body seeming to sag or settle down and in, her face partially shadowed, studio lighting coming from in front of and from her left as she faces the camera. She looks… In the spirit of Blaeser's efforts to conjure "cultural or transcendent nexus of connections" and "associative links," stop the sentence there, resist the impulse to ascribe to the photographed woman a physical and/or emotional state. Look instead at the image's date stamp: "about 1890." What is it about 1890? The closing of the frontier. Wovoka. The Ghost Dance. The massacre at Wounded Knee on a bitterly cold late December morning. The photograph is about 1890, no doubt about it, about the desire of the settler-colonial society to capture the indian inexorably and inevitably passing away.

The last photograph in The People Named the Chippewa, the twenty-third, would seem at first glance to sound the same old story, proclaiming the inevitable end for a person and a people: Anishinaabe grave houses on the Leech Lake Reservation [fig. 4]. The photograph is Vizenor's, one of nine taken by him that are included in the text, and by the time one arrives at the last photograph the reader should recognize that it needs to be read in light of the other eight taken by Vizenor and against the same old story of the vanishing indian. Vizenor's photographs include a smiling Jerry Gerasimo standing amidst a cluster of young students captivated by a camera at the Wahpeton Indian School in 1969; an Anishinaabe probation officer sitting at ease atop a three-foot high stump beside a building in some disrepair; students at the Indian Circle School on the White Earth Reservation; Dennis Banks in profile wearing an AIM beret and again in regalia with Kahn-Tineta Horn at a tribal dance; AIM members in Minneapolis at the Bureau of Indian Affairs in 1968. In a word, these are contemporary natives, not anachronisms. The photographs of children are especially telling, for they harken to the needs of future generations. They also resonate with many of the archival images from the Minnesota Historical Society in the book, for six of the first eight of those images are of Anishinaabeg families.

One sees kinship and community on display both in the selection of historical photographs ranging from the 1890s to 1945 featuring families and multiple generations of community members and in Vizenor's photographs of children in educational settings. The last two photographs in the volume, both taken by Vizenor, highlight the importance of traditional cultural practices and place to the people: the former an image of an honoring ceremony for John Ka Ka Geesick held in the Warroad, Minnesota high school gymnasium and the latter the image of traditional Anishinaabe grave houses built low and peaked against the elements in a clearing of a mixed hardwood-coniferous forest.

Given that Vizenor, in his words, "create[s] imagic scenes... in narratives and stories," the use of photographs from the Minnesota Historical Society and those that he has taken is not surprising (Native Liberty 5). Nor is it surprising that many of the photographs in The People Named the Chippewa feature families, for, again to quote Vizenor, "some photographs of ancestors are stories, the cues of remembrance, visual connections, intimations, and representations of time, place, and families, a new native totemic association alongside traditional images and pictomyths” (Native Liberty 179).[4] Vizenor recognizes that "The Anishinaabe pictomyths, transformations by vision and memory, and symbolic images are totemic pictures and [while] not directly related to emulsion photographs; yet there is a sense of survivance, cultural memory, and strong emotive associations that bears these two sources of imagic presence in some native families" (Native Liberty 180).

Louise Erdrich's relationship to her daughters, particularly to eighteen-month-old Nenaa'ikiizhikok, and to motherhood and family are foundational to Books and Islands in Ojibwe Country, so it is unsurprising that her illustrations in the text include drawings of the child Erdrich bore after she turned forty and of mother and child together. Named for one of the four spirit women tasked with watching over the world's waters, Nenaa’ikiizhikok is rendered by Erdrich as the child explores her immediate surroundings first at the Lake of the Woods and then at Rainy Lake, as a loon paddles close to check her out, with her father Tobasonakwut, and as Erdrich nurses her. Images of family rightly capture our attention, but Erdrich's first two illustrations ought capture our attention as well, for they accentuate the link between word and image, between sheets of paper and sheets of water, between narrative, kin, connection, and community.

The first drawing (4) is of books on and indeed partially in the water with hardwoods growing from the covers of two volumes [fig. 5]. Sharp lines of demarcation give way to an image that accentuates connections and interconnectedness as the line between water and book is blurred, or rather, as water and book, natural world and text, merge. Moreover, just as with words and images complementing each other Erdrich’s text makes clear the connections between books and islands, both and water, all and the natural world, so too does Books and Islands in Ojibwe Country highlight the connection Anishinaabeg have with water in general and her partner Tobasonakwut’s band has with the Lake of the Woods in particular.

The second drawing (15), that of her favorite tobacco to give as gift, reminds us of the connection between self and others here on turtle island and between the

corporeal and the spirit world that are key features of traditional Anishinaabe worldview [fig. 6]. The image highlights family with Nokomis prominently featured, the word translated into English is my grandmother, but the word also orients us to Anishinaabemowin more generally, which is to say to the place from which the language springs. In Erdrich's words, Anishinaabemowin, “is adapted to the land as no other language can possibly be. Its philosophy is bound up in northern earth, lakes, rivers, forests, and plains... it is a language that most directly reflects a human involvement with the spirit of the land itself” (Books and Islands 85). Her words echo Vizenor's here, as he notes in The People Named the Chippewa that "the words the woodland tribes spoke were connected to the place the words were spoken" (The People Named the Chippewa 24). In such a constellation of connections and interconnectedness kin and kinship go beyond blood to encompass all our relations.

Such an understanding is radically opposed to the ideology of acquisition, possession, and extraction traditionally and typically governing settler-colonial society and the West, for all the words and actions to the contrary that countries and global multinational corporations tout as evidence of a green sensibility and mindset, words too often merely lip service and actions too often questionable at best. Thus, while highlighting kinship and connection and another way of being in and with the world, Erdrich's second image makes clear how this other way is transgressive insofar as Nokomis and all it signifies breaks the frame on the label meant to contain it.

Together, the first two images contextualize and knit together the third image (17), that of Erdrich reading as Nenaa'ikiizhikok nurses at her breast. [fig 7]. The child is settled into the crook of her mother's left arm and Erdrich's left hand is cupped around the side of her daughter's head. Erdrich's right arm is also bent at the elbow in order for her to clasp with her right hand an open book at reading distance. Vizenor holds that the eyes and hands of "wounded fugitives" captured in photographs taken in service of the dominant society can nevertheless be "the sources of stories, the traces of native survivance" (Fugitive Poses 158, emphasis added). Fittingly, then, in Erdrich's third drawn image the nursing blanket is drawn so that mother, her hands, child, open book, and sustenance merge. What comes with that merging is nothing less than, to deploy Vizenor's language again, the "traces of native survivance." So ends the volume's first chapter. The third image's emphasis on connection will be repeated in the text's final image, presented to the reader after Erdrich returns on the text's last page to the question she wants to answer, is driven to answer, and with which she opened Books and Islands in Ojibwe Country: "Books. Why? (4, 141). We are prepared for the answer when it comes at text's end: "so that I will never be alone" (141): which is to say, so that she will be and stay connected, so that she will recognize and nurture connections. We are also prepared for the final

drawing (141) where books, driftwood, rocks, and shore are all rendered together to close a text that opens our eyes to connection not separation [fig. 8].

Coming roughly a third of the text after the drawing of mother and child and reading, her drawing of the pictograph of the Wild Rice Spirit on a shoreline rock wall of an island in the Lake of the Woods helps to link people, place, and worldview for the reader. Standing before the pictograph on Painted Rock Island, Erdrich writes that she was "trying to read it like a book" but that she did not "know the language" (51). After Tobasonakwut utters the figure's name, Manoominikeshii or, in English, wild rice spirit, the pictograph resolves, for "Once you know what it is, the wild rice spirit looks exactly like itself. A spiritualized wild rice plant" (51). Spirits of things have, Erdrich tells us, "a certain look to them, a family resemblance" (51, emphasis added). The emphasis on family, on representation, and on reading is concretized when Tobasonakwut, knowing the year's wild rice crop is destined to be abysmally poor because the provincial government saw fit to raise the lake's water level against the protest of the First Nations peoples and in the process ruin thousands of acres of wild rice beds (52), likens the failed harvest to parents who had no children, for lines of kinship are broken both for present and future generations. All our relations suffer.

Erdrich offers her drawing of two pictographs paired and read together on a Lake of the Woods rock face in order to show what the familiar phrase all our relations means for the Anishinaabe. At the base of the rock, which is to say closest to the water by turns still, lapping, rolling, pounding against it, an image of a name, a sturgeon, “floats” above the image of a divining tent (76-77). The rendering includes spirit lines emanating from the lake sturgeon. Here, then, we are encouraged to see the connections between sturgeon and humans and between the physical world and the spirit world. Beyond being a rendering of those connections, the pictographs also proclaim a desire to see and maintain the link between worlds and between human and other-than-human persons via the representation of the divining tent. It is fitting, then, that the drawing of those pictographs is the penultimate one in the section of Books and Islands in Ojibwe Country devoted to the Lake of the Woods, to be followed by the drawing of daughter atop her father’s shoulders, for the former image resonates and informs the latter, and vice versa, helping us to see.

Erdrich's drawings of mother and child stand in telling and welcome contradistinction to one of the three pictures of Clement Vizenor from the June 1936 newspapers. The headshot used by the Minneapolis Journal is cleaved from the last photograph taken of father Clement and son Gerald together [fig. 9]. To invoke Vizenor on photographs, the Journal photograph is “not the real,” it and the other headshots of Clement are “not the actual representations of time or culture” (Native Liberty 165). Indeed, all three headshots are doubly disconnected—severed both from their original genres—family and personal photographs—and from the lived experiences of native people. If “the stories of photographic images create a sense of both absence and presence: simulations are the absence, and stories of actual family images are an obvious sense of presence” (Native Liberty 165), the headshots of Clement William Vizenor offer us only absence, particularly the one published in the Minneapolis Journal.

That last photograph adorns the dust jacket cover of Interior Landscapes: Autobiographical Myths and Metaphors (1990) and serves as the volume's frontispiece. The text includes both the narrative of Vizenor's effort to get the police records of his father's unsolved murder and his poem of the Journal headshot, entitled "The Last Photograph." That poem situates Clement and others from White Earth in the Twin Cities: "reservation heirs on the concrete / praise the birch / the last words of indian agents / undone at the bar" (30-31). Imagine those last words—you'll have support there, there will be work, housing, promise, a future—words lost in the reality of a "crowded tenement" where "our rooms were leaded and cold / new tribal provenance / histories too wild in the brick / shoes too narrow" (31). The poem culminates with the last photograph opening the final stanza, father holding son, a young man who "took up the cities and lost at cards" (31). While for Densmore, the birch trees are a vivid reminder of what is no more for the people, an image of what has been lost, Vizenor's poem indicates that such need not necessarily be the case. Despite the last words of the indian agents, the birch can still be praised, and Vizenor has long suggested that doing so is both an act and instance of survivance.

For Vizenor, the "natural motion in literature and art," the theory of transmotion, is connected to "the original scenes of cosmoprimitive art, or the actual portrayals of native motion and visionary images on rock, hides, ledger paper, and canvas" (Treaty Shirts 115, 114). Those visionary images are rooted in specific native cultures and worldviews. Here, praising the birch sounds a connection to material culture and traditional practices: particularly birchbark canoes (fittingly seen in one of the archival photographs Vizenor includes in The People Named the Chippewa) and Midewiwin scrolls. The archival image shows multiple generations of a family around and, in the case of the youngest, atop a canoe overturned on the shores of Cass Lake, which, again fittingly, is one of the places in northern Minnesota where Densmore did her fieldwork and collecting. The photograph bears the title "Anishinaabe family on the shore of Cass Lake, about 1900." Read in light of and in the spirit both of Vizenor's thinking and of Blaeser's efforts to create with her photographs and picto-poems a nexus of connections and the possibility for unexpected associative links for her audience, the image is about 1900, before and after, insofar as it highlights kin and connection as foundational to individual, to family, and to community identity and survival.

In the same light, Blaeser writes "Poetry is connections" in the Preface to her first collection of poetry, Trailing You (1994), and dedicates the book to those to whom she is connected by blood and history:

for the Blaesers, Bunkers and Antells

for you who carry those names in your blood

for you who carry those names in your spirits. (n.p)

Given the dedication and Preface, it makes sense that the volume's frontispiece consists of thirteen snapshots of multiple generations of her family, the photographs overlapping arrangement stressing connection [fig. 10].

Fig. 10

What is more, the overlapping layout of photos "invites [our vision] [to go] beyond the frame" ("Refraction and Helio-tropes" 188). We are encouraged to see not hard and fast boundaries but rather a fluid borderlands featuring family: twelve of the thirteen photographs are of more than one person and at least seven of those twelve include multiple generations in each shot. The sole photograph of a single person is of the poet herself, positioned such that we see what she "sees": kinship and connection.

Blaeser says that she situates her photographs in the tradition of Anishinaabe dream song, and that in so doing her images offer pathways that "invite a moment of transcendence or enlightenment" ("Refraction and Helio-tropes" 179). Her photograph for the cover of Copper Yearning, entitled "Where Amber Light Spills," uses reflection to signal to the reader the role it will play the poems to follow while also sounding the primacy of connections and offering us an invitation to enlightenment. Rooted in Anishinaabe worldview, the invitation offered by the photograph is to a moment of eco/ontological enlightenment concerning the connections between the various layers of the cosmos as understood by the Anishinaabe—sky, the earth on turtle's back, and the world that lies beneath.

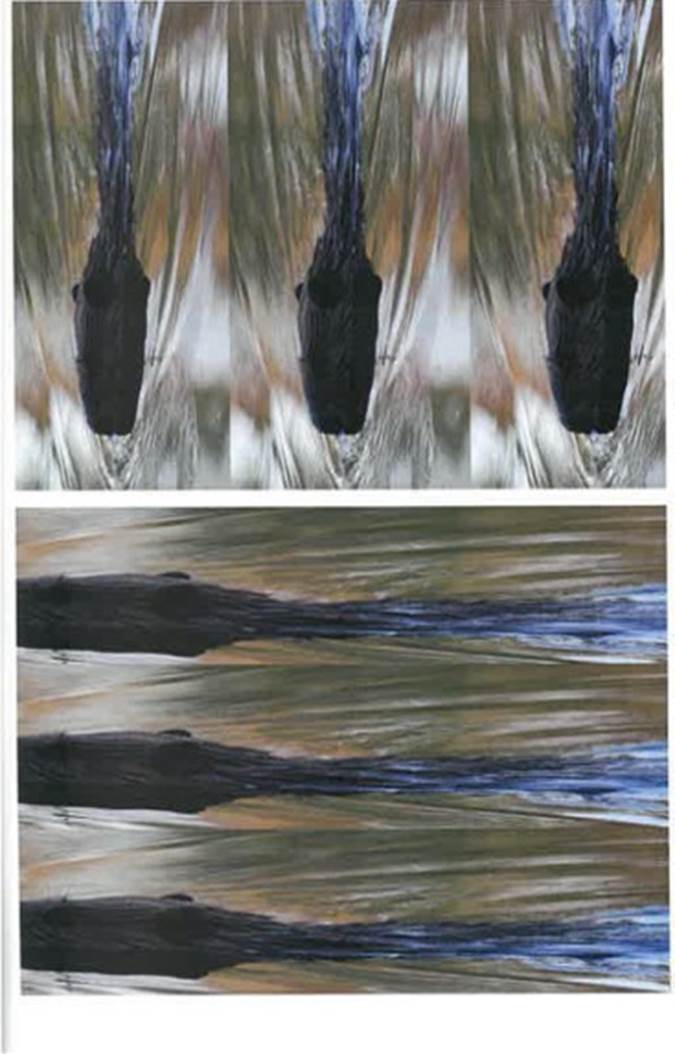

Still images, Blaeser's photographs picture her attempt to "insinuate the animate, the cyclical, the eternal—not necessarily motion in the photo, but the sense of possibility suggested through visual vibrations or photographic gesture" ("Refraction and Helio-tropes" 178). The cover image insinuates motion, starts to become a moving image, with both its title and the faint trace of radiating concentric circles on the water's surface. A trick of light? the after-image of a panfish after it has kissed the surface? the dream of a water body? all? something else? No matter, the trace of motion carries over and across to the other Blaeser photograph in the volume and the picto-poem "Dreams of Water Bodies Nibii-wiiyawan Bawaadanan" (6-7) opening the section “Geographies of Longing” [fig. 11].

Image, English, and Anishinaabemowin come together in the picto-poem to recast Wazhashk so that it is no longer "belittled or despised / as water rat on land." Rather, Wazhashk is recognized for who it is,

|

hero of our Anishinaabeg people in animal tales, creation stories whose tellers open slowly, magically like within a dream, your tiny clenched fist so all water tribes might believe. |

ogichidaa Anishinaabe awesiinaajimowinong, aadizookaang dash debaajimojig onisaakonanaanaawaa nengaaj enji-mamaajiding gdobikwaakoninjiins miidah gakina Nibiishinaabeg debwewendamowaad. (Copper Yearning 7) |

Blaeser's photograph highlights motion and repetition as an overhead shot and a side shot of a swimming Wazhashk are each repeated twice: moreover, the overhead shot become three in the image is oriented so that Wazhashk swims toward the viewer while from the side the image in triplicate reveals Wazhashk swimming from right to left, which is to say against the grain with which the West's eye is schooled to read. Invited to see from another perspective, from an Anishinaabe perspective, we can begin to see "this good and well-dreamed land minwaabandaan aakiing maampii" (7), and with it begin to see the importance of sacrifice as well, reciprocity, thinking for the many rather than simply for the self, thinking and acting for all our relations. From there it is a small step back to the volume's dedication "...For the Water Protectors—ogichidaakweg / who walk for health of nibi..." (Copper Yearning n.p.) and ahead to its Envoi where Anishinaabe water drums sound and the "frayed history" of a land and a people "we patch / with the patient pitch of story" (Copper Yearning 141).

Fig. 11

For Blaeser, the both-and nature of photographs opens rather than forecloses possible illuminations, because, made up of both presence and absence, photographs “simultaneously invoke the material and the immaterial, the known and the unknown” (181). One sees this in a picto-poem not included in Copper Yearning, although the verse portion serves as the volume's proem, "Wellspring: Words from Water" [fig.12].

Fig. 12

"Wellspring: Words from Water"

A White Earth childhood water rich and money poor.

Vaporous being transformed in cycles—

the alluvial stories pulled from Minnesota lakes

harvested like white fish, like manoomin,

like old prophecies of seed growing on water.

Legends of Anishinaabeg spirit beings:

cloud bearer Thunderbird who brings us rain,

winter windigo like Ice Woman, or Mishibizhii

who roars with spit and hiss of rapids—

great underwater panther, you copper us

to these tributaries of balance. Rills. A cosmology

of nibi. We believe our bodies thirst. Our earth.

One element. Aniibiishaaboo. Tea brown

wealth. Like maple sap. Amber. The liquid eye of moon.

Now she turns tide, and each wedded being gyrates

to the sound, its river body curving.

We, women of ageless waters, endure:

like each flower drinks from night,

holds dew. Our bodies a libretto,

saturated, an aquifer—we speak words

from ancient water.

The image articulates the both-and nature of still photography and the both-and nature of Anishinaabe cosmology and a layered universe where lines separating the physical and the spiritual, for instance, are often blurred. Water, mist, sky merge in the image such that not far out beyond the dock it become difficult to see where sky and water meet. A tree-lined shoreline on the left at an indeterminate distance merges with mist and sky as our eye follows it from the left edge of the frame toward the middle of the photographic field. We have no idea where the far shore is out past dock’s end. Even the near shoreline is figuratively blurred, as lake water rides over the dock’s deck.

The photograph plays with time as well, which is in keeping with Blaeser’s desire to “disrupt a sense of temporal reality” in and with her images. Not knowing the camera’s orientation to the sun, it becomes difficult to determine whether it is morning or evening (Blaeser "Refraction and Helio-tropes" 178). Time of year is also at least to some degree indeterminate: not winter, obviously, but late spring, early summer, mid-summer, late summer, early fall before the leaves turn? An example of Blaeser’s effort to “privilege photographic feeling over fact, spiritual intuition over physical data” ("Refraction and Helio-tropes" 178), the photograph invites us to feel comfortable in and with indeterminacy, to see connections both physical and spiritual, to get our feet wet.[5]

Here, then, poem coppers word and image, enabling the picto-poem to resonate beyond this particular moment “in-not in” time and space. The connections captured in the photographic image magnify to include in the one-stanza verse Mishibizhii and the Thunderers, winter windigos, earth and moon, Anishinaabe creation stories, women, mother and daughter. Thunderers balance Misshepishu, and vice versa, reminding us of the need to have and maintain balance within, with, and between all things. Windigo, gone mad due to a combination of appetite and excess, serves to caution us to take care and not to take too much. “copper” is an inspired and telling choice of words, for it serves to connect picto-poem to the homeland of the Anishinaabeg and to their own native literary history and tradition. As Anishinaabe William Warren’s History of the Ojibwe People (1885) tells us, Anishinaabeg considered copper sacred and used it for “medicinal rites,” in Midewiwin ceremonies, and, in at least one instance, as the “sheet” upon which with “indentations and hieroglyphics” was marked a family’s history through the generations (89).

Stories of spirit beings copper narrator to a network of balance because, remarking connections and interdependencies, those stories are a pathway to enlightenment and healing. What might seem a picture of ruptured connections, lake water washing over dock surface, is anything but, for at times just beneath the surface of our awareness and understanding is the truth of connection, the firm platform upon which, once recognized, we can stand.

This recognition pictured in the image, articulated in its accompanying verse, resonates forward and backward in time. In 1998, with deep loss threatening to rive, solace:

Mother, Auntie, Grandma, Marlene,

we believe you inhabit these lands.

Your spirit embedded here

blowing like Bass Lake breezes

across our fish-wet hands.

Pushing up moccasin flower shoots

along the Tamarack trails.

Casting before us scents

we know to be our relatives

cedar, pine, and sweetgrass.

Etching story words and pictures

in white-gray birch bark patterns.

Calling names in the language of birds

Nay-tah-waush, Mah-no-men

Gaa-waababiganikaag. (AI 48)

Back as well as forward: child to mother, mother to child, throughline made explicit via words and water: “Rills,” “Aniibiishaaboo,” “Amber.” Amber Dawn, Blaeser's daughter.

As was often her wont, Densmore's close to "The Study of Indian Music" gives the reader the indian dead and gone. At the same time her close imagines that careful attention to the music, song, and other elements of material and symbolic culture gathered thanks to the acquisitive impulse of ethnographers committed to collecting and persevering and the generosity of native sources affords one the chance to "find [in the collected materials] some trace of kinship, some new reason that, as we stand beside the grave of the Indian, we may say 'Here lies my brother'" (197). Some kinship that: it is easy enough to imagine a connection with what you have cast as other once they have been dead and buried, but it is no comfort to those erased.

Birch trees to birch bark: Densmore to Blaeser, Erdrich, and Vizenor. In "Literary Transmotion: Survivance and Totemic Motion in Native American Indian Art and Literature," Vizenor describes Densmore as "the honorable recorder of Native songs and ceremonies" and she deserves our thanks for her labors, for all that she collected over the course of her long career (18). We are the richer for her efforts. Still, it bears remembering that, according to Michelle Wick Patterson, when Densmore was asked what led her to collect and study Native American music, song, and material culture, her answer was nearly always the same: she recalls that as a child in Red Wing, MN"'I heard an Indian drum'" as she settled into bed for the night and drifted toward sleep (Patterson 29). "Unconsciously," she wrote, the sound of distant drumming "called to me, and I have followed it all these years" (Patterson 29). Taken together with the story of Densmore's attempt to take photographs of natives without their knowledge and, according to Patterson, her efforts from first to last to approach the study of Native American cultures with "scientific detachment," the sound of a distant drum becomes an instance of distancing, and with that distancing a separation between Densmore and her informants comes into focus (Patterson 44). From such a distant vantage point it is easy for Densmore to picture the people as objects, as indians. Stephen Smith notes that "while Densmore's commitment to preserving Indian culture was progressive for her time, she still harbored many of the common American prejudices about Indians. She viewed them as a childish race with a 'native simplicity of thought'." Moreover, he explains that, "Over time, Densmore's attitudes about Indian character hardened. As she grew more scientific and less romantic in her analysis of Indian music, her view of contemporary Indians grew astringent.” According to Smith, "Densmore spent her adult life working among Native Americans, but not with them. She erected an imposing, patronizing personal barrier that permitted few—if any—Indians to get past."[6]6

Over against the isolation, emptiness, and loss Densmore inscribes in 1941 with the stark image of birches standing on a hillside, one sees the recognition of presence over absence and of connections over separation articulated by "Etching story words and pictures / in white-gray birch bark patterns" (Absentee Indians and Other Poems 48); by a bookstore and publishing house named Birchbark Books in the spirit of mazinibaganjigan, a word used "to describe dental pictographs made on birch-bark, perhaps the first books made in North America" (Books and Islands in Ojibwe Country 5); by a recognition that "The Anishinaabeg drew pictures that reminded them of ideas, visions, and dreams, and were tribal connections to the earth. These song pictures, especially those of the Midewiwin, or the Grand Medicine Society, were incised on the soft inner bark of the birch trees" (The People Named the Chippewa 26).

awasi- signals movement, as does transmotion. Vizenor makes clear that the latter is not just any movement; rather, the "literary portrayal and tropes of transmotion are actual and visual images across, beyond, on the other side, or in another place, and with an ironic and visionary sense of presence" ("The Unmissable" 69, emphasis added). Back then one more time to the beginning that we might move forward and in doing so continue to go beyond the indian. "Our aim" opens the essay, and together those two words sound the critical importance of the group rather than the individual and invoke the spirit of collective action to protect and to right wrongs from which arose the American Indian Movement on the streets of Minneapolis in the 1960s. Whether one agrees with AIM's leadership or is critical of it, or both, the call to join and to act in the name of and for the betterment of many resounds.

Back then, too, with Blaeser, Erdrich, and Vizenor to the beginning, the Anishinaabe creation story and the earth on Turtle's back. Basil Johnston's rendering in Ojibway Heritage makes clear the dynamic nature of what Kitche Manitou beheld in vision and then created—a world of both change and constancy: nothing immutable, nothing static. No wonder then that in his first novel Vizenor made clear that terminal creeds are terminal diseases. What is more, restoring the earth after it was flooded in response to man's foolishness necessitated collective acts of kindness, generosity, and sacrifice. Turtle offers its back to an exhausted Sky Woman so that she might land and rest, waterdivers one after another dive deep reaching for the bottom, failing again and again to surface with a bit of earth until finally, Wazhashk, least of all, at last succeeds. And so the earth on Turtle's back comes to be. Erdrich offers us her drawing of a snapping turtle, remarking literally and figuratively the link between the number of plates that comprise its shell and human females and motherhood. Blaeser's image of Wazhashk links Copper Yearning's opening proem "Wellspring: Words from Water," the "Dreams of Water Bodies" following it, and the Anishinaabe creation story and in doing so offers a gentle admonition that we view muskrat and so much more in a different light.

Like Erdrich and Blaeser, Vizenor would have us see differently. Like Wazhashk, his efforts are timeless. Vizenor has long advocated for continental liberty. Indeed, it is enshrined in the Preamble of the Constitution of the White Earth Nation, a document for which he served as the principal writer:

The Anishinaabeg of the White Earth Nation are the successor of a great tradition of continental liberty, a native constitution of families, totemic associations. The Anishinaabeg create stories of natural reason, of courage, loyalty, humor, spiritual inspiration, survivance, reciprocal altruism, and native cultural sovereignty. (Constitution)

Fittingly, Vizenor links continental liberty, families, and totemic associations that include human and other-than-human persons. There are small triumphs in the spirit of continental liberty. Land bridges and safe passage corridors have been created. Dismantling dams and constructing water ladders to bypass those blockages that cannot be removed has enabled the return of nameh to waters from which they had long been absent; they have now more and more the freedom of their traditional range.[7]

Still, there are painful truths. As I type this sentence, 8 December 2023, the news in the Star Tribune this week included word of a cougar roaming in the north suburbs of Minneapolis-St. Paul; that story was followed two days later with an account of the cougar's encounter with a moving Humvee. The cougar had no chance. Nor did Clement Vizenor years before, his blood spurting from a fatal neck wound long before any urban birdsong welcomed a Sunday dawn. Just shy of four weeks earlier Truman Vizenor fell to his death from a train bridge, arrow straight parallel rails and uniform cross-ties leading nowhere, save trouble. In contradistinction to the image of those rails and where they lead, Vizenor's Interior Landscapes: Autobiographical Myths and Metaphors offers not the Lake of the Woods or Rainy Lake in the northern borderlands but a sheet of water on the White Earth Reservation, “small, round Vizenor Lake” (17). The sheet is small, to be sure, if not round, precisely. The description is revealingly apt nevertheless: round invokes circles, cycles, continuity, connectedness, connections, dare we say a seamless whole, and in doing so sounds a fuller, wiser notion of kin.

Envoi[8]

Back as well as forward, forward as well as back; beyond, over across; words and water: awasi-; moving images. A dibaajimowin then, a story from memory: in the land of the Anishinaabeg, an easy evening paddle south with Kim Blaeser, Bob Black, and a group of college students, returning from a visit with the North Hegman Lake pictographs.

We let the students find their pace and rhythm. They ease on until they are some ways in front, leading us home as the setting sun casts evening glow that makes for telling reflection. We had lingered long on the water with the pictographs, offered tobacco, sketched, taken photos, talked quietly between canoes, no matter that it will mean a portage uphill through a shadow-darkened stand of red pine.

But that is still to come. It is a fine evening for paddling, not a breath of wind. Then, up ahead, voices of young women lift in song, carry over Northwoods water.

A blessing

Nagamon

Sing

[To hear the complete poem, visit: https://www.ttbook.org/interview/benediction-song-giving-back]

"A Song for Giving Back"

"Sing, spirit of water," Blaeser writes, recites, and in a public performance of "A Song for Giving Back" encourages her audience to proclaim. In Chippewa Customs, Densmore included the stories of the spirit of water and the spirit of the woods in a section entitled "Pastimes for little children" as examples of the "simple means devised for entertaining little children," many of which have been forgotten" (Chippewa Customs 62). Blaeser has said that native people don't educate their children, they story them, and from that perspective the spirit of water is not an entertaining pastime to help children while away the hours; it is not something from a past time, but rather is a reminder of an animate and interconnected world, one full of humans and other-than-human persons, a world of flow and flux, of change and constancy. It is a world in motion, a world rendered and enriched by "stories of native survivance [that] are instances of natural motion, and transmotion, a visionary resistance to cultural dominance" (Vizenor, "The Unmissable" 65) one finds in the words and images offered by Blaeser, Erdrich, and Vizenor.[9]

Coda

In the spirit of connection and community, of a generation giving to those that follow, a collection of moving images.

Gerald Vizenor with his son Robert at the marker of a distant relative on Madeline Island

Vizenor at the opening of the Oshki Anishinabe Family Center, created "to celebrate the idea of tribal families and communities" (Interior Landscapes 221)

Louise Erdrich at a gathering for young readers and writers in Buffalo N.Y. 2016

(photographs by Bruce Jackson).

In-Na-Po "is a community committed to mentoring emerging writers, cultivating Indigenous literatures and poetics, supporting tribal languages and sovereignty, and raising the visibility of all Native writers" (https://www.indigenousnationspoets.org/). The video of "Poems for a Tattered Planet" can be found at the In-Na-Po website by clicking on the 2023 Retreat link under the Events header.

Kimberly Blaeser and the 2022 Indigenous Nations Poets (In-Na-Po) Fellows in Washington D.C.

A Poetry Out Loud event honoring first-place winner Amber Blaeser-Wardzala (center) and runner-up Alexa Paleka and featuring a reading by Kimberly Blaeser as the Wisconsin Poet Laureate.

Works Cited

Archabal, Nina Marchetti. "Frances Densmore: Pioneer in the Study of American Indian Music." Women of Minnesota: Selected Biographical Essays. (revised edition). Eds. Barbara Stuhler & Gretchen V. Kreuter. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1998. 94-115.

Blaeser, Kimberly. Absentee Indians & Other Poems. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State

University Press, 2002.

---. Copper Yearning. Duluth, MN: Holy Cow Press, 2019.

---. "The Language of Borders, the Borders of Language in Gerald Vizenor’s Poetry." The Poetry and Poetics of Gerald Vizenor. Ed. Deborah Madsen. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2012. 1–22.

---. “Refraction and Helio-tropes: Native Photography and Visions of Light.” Mediating

Indianness. Ed. Cathy Covell Waegner. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press, 2015. 163-195.

---. Trailing You. Greenfield Center, NY: The Greenfield Review Press, 1994.

Brill de Ramírez, Susan. "The Anishinaabe Eco-Poetics of Language, Life, and Place in the Poetry of Schoolcraft, Noodin, Blaeser, and Henry." Enduring Critical Poses: the Legacy and Life of Anishinaabe Literature and Letters. Eds. Gordon Henry Jr., Margaret Noodin, & David Stirrup. SUNY Press, 2021. 79-106.

Constitution of the White Earth Nation. Ratified 2009.

[https://nniconstitutions.arizona.edu/sites/default/files/2022-01/White%20Earth%20Nation_1.pdf]

Deater, Tiffany. "Against the Ruins." 2023. (video)

Densmore, Frances. Chippewa Customs. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Bureau of Ethnology Bulletin 86, 1929.

---. "The Importance of Recording Indian Songs." American Anthropologist 47 (1945):

637-639.

---. “The Native Art of the Chippewa.” American Anthropologist 43 (1941): 678-681.

---. "The Study of Indian Music." The Musical Quarterly Vol. 1, No. 2 (Apr. 1915): 187-197.

Erdrich, Louise. Books and Islands in Ojibwe Country. Washington, D.C.: National

Geographic Society, 2003.

“Feud Hinted in Two Deaths.” Minneapolis Star 29 June 1936: 1.

“Giant Hunted in Murder and Robbery Case.” Minneapolis Journal 30 June 1936: 1.

Hearne, Joanna. "Telling and retelling in the 'Ink of Light': documentary cinema, oral

narratives, and Indigenous identities." Screen 47.3 (Autumn 2006): 307-326.

Jensen, Joan & Michelle Wick Patterson, eds. Travels with Frances Densmore: Her Life, Work, and Legacy in Native American Studies. Lincoln, Ne: University of Nebraska Press, 2015.

Johnston, Basil. Ojibway Heritage. Lincoln, Ne: University of Nebraska Press, 1976, 1990.

LaLonde, Chris. “Being Embedded: Gerald Vizenor’s Bear Island: The War at Sugar Point.” The Poetry and Poetics of Gerald Vizenor. Ed. Deborah Madsen. Albuquerque: University of Mexico Press, 2012. 205-222.

---. "Continental Liberty, Natural Reason, Survivance: Gerald Vizenor's Sojourning in the Borderlands." Theorizing the Canada-U.S. Border. Eds. David Stirrup & Jeffrey Orr. Edinburgh University Press, 2023. 114-130.

---. "Louise Erdrich's Books and Islands in Ojibwe Country: Writing, Being, Healing, Place." Enduring Critical Poses: the Legacy and Life of Anishinaabe Literature and Letters. Eds. Gordon Henry Jr., Margaret Noodin, & David Stirrup. SUNY Press, 2021. 2-16.

---. "Addressing Matters of Concern in Native American Literatures: Place Matters."

Indigenizing the Classroom: Engaging Native American/First Nations Literature and Culture in Non-Native Settings. Ed. Anna M. Brígido-Corachán. Publicacions de le Universitat de. València, 2021. 41-54.

---. “Place and Displacement in Kimberly Blaeser’s Poetry.” Transcultural Localism:

Responding to Ethnicity in a Globalized World. Ed. Yiorgos Kalogeras, Eleftheria

Arapoglou, & Linda Manney. Heidelberg: Universitaetsverlag Carl Winter, 2006. 47-58.

“Miss Frances Densmore to be Honored by D.A.R.” Minneapolis Tribune 30 June 1936: 13.

Nichols, John and Earl Nyholm. A Concise Dictionary of Minnesota Ojibwe. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1995.

Noodin, Margaret. Bawaajimo: A Dialect of Dreams in Anishinaabe Language and Literature. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press, 2015.

“Paper-Hanger Slain in Alley.” Minneapolis Tribune 29 June 1936: 6.

Patterson, Michelle Wick. "She Always Said, 'I Heard an Indian Drum'." Travels with Frances Densmore: Her Life, Work, and Legacy in Native American Studies. Eds. Jensen & Patterson. Lincoln, Ne: University of Nebraska Press, 2015. 29-64.

Povinelli, Elizabeth. "The Urban Intensions of Geontopower." e-flux Architecture (May 2019): https://www.e-flux.com/architecture/liquid-utility/259667/the-urban-intensions-of-geontopower. Accessed 6 December 2021.

"Reframing Our Stories." Minnesota History Center exhibit. October 2023-October 2025.

https://www.mnhs.org/historycenter/activities/museum/our-home/reframing-our-stories

[accessed 3 November 2023]

“Seize Suspect in Alley Fight.” Minneapolis Tribune 30 June 1936: 14.

Smith, Stephen. "Introduction."

https://americanradioworks.publicradio.org/features/densmore/docs/authorintro.shtml

---. "Densmore's Attitude Toward Indians."

https://americanradioworks.publicradio.org/features/densmore/docs/attitude.shtml

Stuhler, Barbara & Gretchen V. Kreuter. Women of Minnesota: Selected Biographical

Essays. Revised Edition. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1998.

The Ojibwe People's Dictionary. https://ojibwe.lib.umn.edu/ (online resource).

Vizenor, Gerald. Fugitive Poses: Native American Indian Scenes of Absence and Presence. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1998.

---. Interior Landscapes: Autobiographical Myths and Metaphors. Minneapolis:

University of Minnesota Press, 1990.

---. "Literary Transmotion: Survivance and Totemic Motion in Native American Indian Art and Literature." Twenty-First Century Perspectives on Indigenous Studies: Native North America in (Trans)Motion. Eds. Birgit Dawes, Karsten Fitz, and Sabine Meyer. New York: Routledge, 2015. 17-30.

---. Native Liberty: Natural Reason and Cultural Survivance. Lincoln, NE: University of

Nebraska Press, 2009.

---. "The Unmissable: Transmotion in Native Stories and Literature." Transmotion Vol 1. No. 1 (2015): 63-75.

White, Bruce. "Familiar Faces: Densmore's Minnesota Photographs." Travels with Frances Densmore: Her life, Work, and Legacy in Native American Studies. Eds. Jensen & Patterson. Lincoln, Ne: University of Nebraska Press, 2015. 316-350.

Notes

[1] I do not speak Anishinaabemowin. I have relied on Nichols and Nyholm, A Concise Dictionary of Minnesota Ojibwe, the Ojibwe People's Dictionary from the University of Minnesota [online], and the kindness and generosity of those who know the language. That said, any errors are mine and mine alone.

Beginning with awasi- in the title serves both to sound the connection between language and place and to emphasize the efforts by Blaeser, Erdrich, and Vizenor to go beyond the othering representations created and perpetuated by the settler-colonial society. Following their lead, in the essay Anishinaabemowin in general and awasi- in particular sound a rhetorical move, invoking the language of the people as a supplement to the othering representations succinctly captured by Vizenor with the lower case and italicized indian which is deployed throughout the essay to indicate the construction created and perpetuated by settler-colonial society. In the spirit of Vizenor, I also italicize his critical term survivance. As we will see below, Erdrich and Vizenor make clear that the language of the people is intimately connected to their traditional homeland. Fittingly, the first Anishinaabemowin words in Books and Islands in Ojibwe Country, mazina'iganan (books) and mazinapikiniganan (rock paintings), help sound the connection between language and place. Erdrich adds that mazina is "the root for dozens of words all concerned with made images and with the substances upon which the images are put, mainly paper and screens" (Books and Islands 5) and stresses the connection between Anishinaabemowin, identity, and writing as well when she shares that the meaning of Ojibwe she likes best stems from the "verb 'Ozhibii'ge' which is 'to write'" (Books and Islands 11). For a rich examination of Anishinaabemowin, the place from which it originates, and the ends to which it is deployed see Margaret Noodin, Bawaajimo: A Dialect of Dreams in Anishinaabe Language and Literature. For careful readings of the importance of Anishinaabemowin and place in the poetry of Blaeser and Noodin, readings which utilize Noodin's scholarly insights, see Brill de Ramírez, "The Anishinaabe Eco-Poetics of Language, Life, and Place in the Poetry of Schoolcraft, Noodin, Blaeser, and Henry." For work that highlights the relationship between language and place in Vizenor's work see, for instance, LaLonde, "Being Embedded: Gerald Vizenor's Bear Island: the War at Sugar Point;" for an analysis of the role played in and by borders and borderlands in Vizenor's work see, for instance, LaLonde "Continental Liberty, Natural Reason, Survivance: Gerald Vizenor’s Sojourning in the Borderlands;" for the relationship between writing, being, healing, and place in Books and Islands in Ojibwe Country (which does not attend to the text's images, however), see LaLonde, "Louise Erdrich's Books and Islands in Ojibwe Country: Writing, Being, Healing, Place;" for an early attention to place in Blaeser's poetry see LaLonde, “Place and Displacement in Kimberly Blaeser’s Poetry;” for more general work focusing on the importance of place-centered readings and criticism when teaching Native American and First Nations literatures, see LaLonde, "Addressing Matters of Concern in Native American Literatures: Place Matters."

[2] Whether from the 1910s or the 1940s, Densmore's elegiac closing move effectively elides the deracination suffered by the Anishinaabe, and indeed by so many of the first peoples of North America. Often a physical uprooting—think the Trail of Tears, think the Long Walk, think the efforts to have Minnesota Chippewa move to reservations, and so on—it was and is also a social and cultural one. In Anishinaabemowin the word is biigobijigaazo, a person torn or ripped—in this case torn or ripped from place, people, language, culture by the dominant society.

[3] The display behind the Brussels shop window in Blaeser's photograph is worth a moment of reflection, for the dozens of carefully placed figurines are a picture of excess even as they also speak to labor, to the construction of cultural identity, and—with the columns of cast miniature soldiers marshalled together beneath the Belgium flag—colonialism. Elizabeth A. Povinelli's "The Urban Intension of Geontopower" begins with a description of what W.E.B. DuBois saw in his visit to the Belgium park and palace at Tervuren just outside Brussels in 1936: "One can hear DuBois's heels clicking against the polished paving stones and see, as he saw, the copper architectural adornment of elite Belgian institutions as he absorbed the full monstrosity of colonialism (para. 1). Povinelli then quotes Benjamin on the Brussels shopping arcades, "a recent invention of industrial luxury" (Povinelli para 1) to make clear the link between class, capitalism, and colonialism. It is precisely this damning link that with words and images Blaeser, Erdrich, and Vizenor would have us see and see through.

[4] Grounding her argument in Vizenor's thought regarding fugitive poses, Hearne notes that the moving and still images from the late 19th- at least through the mid-20th century serve as a visual archive available for "indigenous repurposing" (308). Whether knowingly or not, The Minnesota History Center's current two-year exhibit "Reframing Our Stories" [running October 2023 to October 2025] resonates with Vizenor's thinking and Indigenous repurposing with the proclamation "From a decades-old box of photographs simply labeled 'Indians,' came the idea for a powerful new exhibit. // Inside the box were dozens of pictures of Native community members, organizations, activities, and events that are relevant today. Now in the hands of indigenous community members, those photos have new meaning." [https://www.mnhs.org/historycenter/activities/museum/our-home/reframing-our-stories]

Opening concurrently at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, Target Gallery, is the exhibit "In Our Hands: Native Photography, 1890 to now" featuring "more than 150 photographs of, by, and for Indigenous people." It "encourages all to see through the lens held by Native photographers." [https://new.artsmia.org/exhibition/in-our-hands-native-photography-1890-to-now].

[5] Getting our feet wet invokes Blaeser’s poem “Where Vizenor Soaked His Feet” and Vizenor’s “shadow presence” throughout Anishinaabe country and in Blaeser’s work. More than simply repeating her literary forebearer, Blaeser unites images and words, storying the image and imaging the story so that photograph and text function in a reciprocal relationship.

[6] See the following documents connected to the Minnesota Public Radio documentary on Densmore's life entitled "Song Catcher: Frances Densmore of Red Wing":

https://americanradioworks.publicradio.org/features/densmore/docs/authorintro.shtml

https://americanradioworks.publicradio.org/features/densmore/docs/attitude.shtml

[7] Continental liberty must also hold for the continents and the earth's waters. Povinelli's "The Urban Intensions of Geontopower" is a part of a larger collaborative effort to voice and address critical questions concerning the past, present, and future of fresh water as a public resource under threat. A photograph heading the essay shows Natives and non-natives standing with Standing Rock against the Dakota Access Pipeline project behind a simple declaration writ large: WE ARE WATER.

[8] Our "Envoi" is offered as complement to Blaeser's "Envoi" in Copper Yearning, grounded as the former is in the "spirit echoes" of pictographs located in the "homelands" (141) of the people.

[9] Nenaa'ikiizhikok in her mother's arms is a vital image of connection, one that stands in contradistinction to the Minneapolis Journal's crop separating father Clement from son Gerald. The clip from Tiffany Deater's "Against the Ruins" showing the photograph rent and a black space opened between father and son is painfully remindful of the terrifying black space of a South Africa diamond mine in Austerlitz, a book Erdrich describes reading during her travels to the lakes and islands of the Minnesota-Canada borderlands and that she finishes the night she and Nenaa'ikiizhikok return home to Minneapolis

the last image, from Trailing You, offers Blaeser's Grandpa Antell holding her youngest uncle, Emmett]. Erdrich sees and would have us see the connection between the blackness produced by resource extraction (call it what it is, a gaping wound) the Holocaust (call it what it is, genocide) and what has happened to the Indigenous people of North America: the biigobijigaazo, the "lightlessness" come of "nine of every ten native people perished of European diseases, leaving only diminished and weakened people to encounter" the horrors of government policies, missionaries, and boarding and residential schools in both the U.S. and Canada (Books and Islands in Ojibwe Country 134-135). For all that, against all that, against all odds, in her infant daughter, asleep beside her, there is "a light" (Books and Islands in Ojibwe Country 135).