Transformations

and Remembrances in the

Digital

Game We Sing for Healing

ELIZABETH LaPENSEE

Métis earthdivers

speak a new language, their experiences and dreams are metaphors, and in some

urban places the earthdivers speak backwards to be better heard and understood

on the earth.

– Gerald Vizenor

It's 2 A.M. I've kept myself awake for this moment. Now is the precious hour when Internet is no longer restricted. This is when I can freely stream audio on SoundCloud without worrying about passing the data limit and being punished by getting cut off for 48 hours. There are nights when I'm frustrated that I can't access downloadable content on my consoles and that, even when the data limit lifts, I have no hope of streaming video. None of that matters when I hear the fresh cut tracks from Exquisite Ghost while looking up at a sky of stars so bright that they light the path walking outside on my way from the house closer to the Internet satellite. We're collaborating on a game, despite our mutually limited Internet, and that's all there is.

These interactions resulted in the design and

development of the musical choose-your-own adventure

text We Sing

for Healing. The game is played by

visiting the website http://survivance.org/wesing/ and using single clicks to navigate through a journey much

like a choose-your-own adventure text game but with a non-linear structure and

a mechanic that calls on players to slow down their clicking and instead stay

on a webpage to listen through music tracks. As expected of the text game

genre, players are usually given a range of text options on each webpage and

reach another webpage by clicking on the linked text of their choice. Uniquely,

the journey options form a looping structure rather than the classic branching

structure known in the genre. From development process to design to aesthetics,

We Sing for Healing can be seen as an

act of survivance.

Games as Acts of Survivance

Backup.

It's 2007 at the Aboriginal History Media Arts Lab in Vancouver, British

Columbia led by award-winning Cree filmmaker Loretta Todd. "We've always had

Internet," she comments as she reflects on how creating in video games and

virtual reality are natural spaces for Indigenous expression while we discuss

an alternate reality game we're working on with Cease Wyss. We could be more

accurately using "social impact game" to describe the plant medicines game during

a phase in game development when the term is emerging. Terminology aside, our ongoing

conversation weaves together stories of spacetime, quantum physics, and

collective consciousness across Cree, Squamish, Anishinaabe, and Métis

perspectives and how these can inform game design. We're inspired by the work

of our families and vital scholars such as Dr. Leroy Little Bear in our

understanding of how our communities have always had virtual communication and

how this connectivity was disrupted by colonization (Todd). Our collaboration speaks

to the ways in which games can create space for Indigenous teachings that reconnect

players with the land utilizing gameplay involving websites, GPS, and physical

rewards including paddle necklaces and the gift of medicinal plant knowledge. Games

with an Indigenous emphasis can take many forms with exciting design

possibilities.

Regardless of differences, digital

games, including videogames, computer games, mobile games, and web games, share

the same essential qualities—they are voluntary, interactive, and determined

by play. While the term "game" has several definitions, ranging from Roger

Caillois who suggests games are voluntary, uncertain, unproductive, and

make-believe acts, to Jane McGonigal who emphasizes that all games are

voluntary and have a goal, rules, and a feedback system (21), the musical

choose-your-own adventure text game We Sing for Healing exemplifies qualities more akin to the

viewpoint of Eric Zimmerman who defines games as interactive narrative systems

of formal play (156-164).

Using a mix of code, design, art, and audio, games are a space for

self-expression and thus can be art in and of themselves. In the context of Indigenous

self-determination, Indigenous games can, like Indigenous art, work "against

colonial erasure... [and mark] the space of a returned and enduring presence"

(Martineau & Ritskes i). Thus, games in their entirety can be considered

acts of survivance, meaning specific instances of the "active sense of native

presence" (Vizenor 1). I first began using this phrase as a step in the social

impact game Survivance, which is

directly inspired by the work of Gerald Vizenor and developed in collaboration

with the Northwest Indian Storytellers Association and Wisdom of the Elders,

Inc. (LaPensée 46). Survivance is

played by choosing a quest at any point in a non-linear journey based on the

Native life journey. The player watches a video of an elder storyteller, walks

through the steps of a quest that is intended to help them address historical

trauma, and then creates an act of survivance as a pathway to healing. In this

context, an act of survivance is self-determined expression in any medium, such

as oral stories, songs, poems, short stories, paintings, beadwork, weaving,

photography, and films, just to name a few possibilities. Games, being a space

of expression, can also be acts of survivance. Specifically, the foundation of

survivance—merging survival with endurance in a way that recognizes

Indigenous peoples as thriving rather than merely surviving—can inform

how a game is developed, how a game is played, and what representations and

aesthetics are found in a game. For example, the

puzzle platformer Never Alone/Kisima

Ingitchuna can be seen as an act of survivance because it is a retelling of

an Iñupiaq family story made by E-Line Media in collaboration with the Cook

Inlet Tribal Council and community members including storyteller Ishmael Hope.

Specifically, video interviews with the community reflect survivance by relating

how stories and traditional teachings are ongoing and actively present today

while also embracing transformation.

We Sing for Healing is an act of survivance in regards to development process, game design, and aesthetics. The game was created with whatever technology was available from a place of limited Internet access; the gameplay expresses non-linear journeying patterned after Indigenous storytelling; and the art, music, and figures in the game echo remembrances and memories of traditional aesthetics which are then remixed [Fig. 1]. Furthermore, the reflective practice of revisiting the game and providing insight as a designer-researcher expands on survivance as an active sense of presence in research that merges Indigenous studies and game studies.

Figure 1. Battle, We Sing for Healing, 2015

Survivance Research

The

revisiting, analyzing, and telling of We

Sing for Healing is situated within survivance as a research approach. Survivance

as it relates to Indigenous epistemology is the ongoing presence of Indigenous

ways of knowing—the ontological understanding of "land, animals, plants,

waters, skies, climate, and spiritual systems" of Indigenous peoples (Martin). This

research upholds Indigenous epistemology by acknowledging the diversity of

Indigenous worldviews while choosing to focus on my worldview as an Irish, Anishinaabe,

and Métis game designer and researcher. It further emphasizes the ways in which

the game development process and resulting game design reflect survivance. This

framework is an active part in communicating the details about We Sing for Healing, which in turn guides future games for myself and other game

developers, just as survivance is "a practice, not an ideology, dissimulation,

or a theory" (Vizenor 11).

Biskaabiiyang Method

As

an Irish, Anishinaabe, and Métis designer-researcher, this reflection is

informed by understanding biskaabiiyang as a researcher reflection method. With

gratitude to the work of Leanne Simpson, biskaabiiyang can be seen as Anishinaabe

survivance involving returning to and sharing teachings and ways of knowing

through research. Biskaabiiyang, which in Anishinaabemowin means "to return to

ourselves," involves returning to our teachings on a pathway of wellbeing. The

phrase has been translated to "returning to our Teachings" (Seven Generations

Education Institute 2), "returning to ourselves" (Simpson 49), and "we are making

a round trip" (Gresczyk 53). The process of biskaabiiyang can occur for the

researcher, the research itself, and those involved in the research. For example,

Anishinaabe researchers return and pick up what was left during colonization

such as language in order to be healthy and thrive (Gresczyk). During this

study, I have returned to We Sing for

Healing in order to share the development process, design, and aesthetics.

This will certainly influence my future work in games and may also inform other

game developers and researchers.

Notably, biskaabiiyang positions research as

ceremony, an aspect in common with other Indigenous research methodologies

(Wilson). The work of decolonizing involves learning our ways of knowing,

learning our medicines, and learning our teachings through knowledgeable elders,

ceremonies, and community members who can facilitate this learning (Debassige).

For myself as Anishinaabekwe, this process involves seeking, doing, learning,

and living a spirit-centered way known as mino-bimaadiziwin (Debassige). While developing

We Sing for Healing, I was living

with the land in a reciprocal way, for example, caretaking plants that I

gathered medicines from. I tend to go back and forth between places with high

speed Internet access and land. The way in which I develop, implement, and

return to design in games is an ongoing journey of biskaabiiyang.

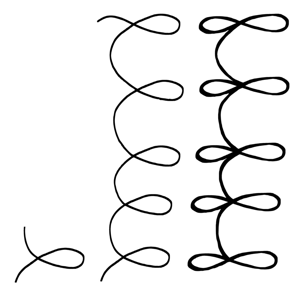

To elaborate, biskaabiiyang journeying begins by

venturing out [Fig. 2]. Then, through iterative cycles of revisiting or

returning, the journey becomes clearer and reveals its interconnectedness.

Finally, the journey completes itself and maintains openness to continue

infinite loops that further clarify and deepen our knowledge. In the context of

games that are ongoing and forever iterating, such as the social impact game about

traditional medicinal plants created with Loretta Todd and Cease Wyss, biskaabiiyang

aligns with the process of iterative game development. Games can transform

through the process of prototyping, playtesting, and revising (Macklin &

Sharp). For example, the medicinal plants game with Cease Wyss continues on today

with QR Codes and other technology that was not available at the point of its origin

design as it continues to respond to the needs of players and changes in

technology and access. Iterative design can be mapped to research as inspired

by the work of Eric Zimmerman, whose research process occurs through the

practice of design. It is important to differentiate that this specific research

about We Sing for Healing involves

revisiting the process and design rather than data collection that occurred

during design and development. The model of iterative design research parallels

biskaabiiyang reflection in that both always consider the researcher to be a

participant.

Figure 2. Biskaabiiyang, 2016

Researcher-Designer

Biskaabiiyang

calls on Indigenous researchers to be active participants in their research. As

both Anishinaabekwe and Michif through my mother Grace L. Dillon, I answer

first and foremost to a strong woman whose scholarship uplifts Indigenous

science fiction and who taught me about survivance and biskaabiiyang. She sees

"we are making a round trip" as a passage into the woods that is intricately

tied to coming back with something meaningful for the community when you

return. As she explained the journey to me, I recalled our walks into the woods

to see the trillium when it reveals itself in early spring. She has been my

lifelong supporter and teacher. Alongside my mother, my Auntie Faith LaPonsie

continuously contributes to my path in teachings. I am grateful for

storytellers and elders including Woodrow Morrison Jr. and Roger Fernandes who

I've crossed paths with and who I've had the joy of developing games with.

From

spacecanoes to bitwork beadwork, I hope for my work to reflect the interweaving

of past/present/future. The stories I recall are remembrances of days when

giant beavers built dams to destroy the people living where later my Anishinaabe

and Métis family found refuge on Sugar Island and where they later maintained their

borderlessness and self-determined sovereignty between Ontario and Michigan. In

the Indigenous futurisms (Dillon) experimental animation Returning, created as a companion piece to We Sing for Healing, I walk in the stars on the path back home and dance

in places where beaded vines telling stories of where our family is from grow

and bloom into medicines we recognize again by name and story. In returning to We Sing for Healing as a designer-player

to reflect on and describe the development process as well as the resulting

design, I am again journeying outward to ultimately journey inward with hope

for sharing the work with communities the reflection may benefit.

Data Analysis and Visualization

Revisiting

and reflecting on We Sing for Healing

is a story in the Indigenous sense—an open-ended narrative reflection (King).

Data collection involved returning to emails during the game development

process, recalling and verifying memories of the creation of the game with Peguis

First Nation mix artist Exquisite Ghost a.k.a. Jordan Thomas, as well as

replaying the game, sketching out the various possible paths of the journey,

and then reflecting through written notes and drawing symbols.

Data analysis follows biskaabiiyang and builds

from the work of Indigenous scholars who have created connections between

Indigenous and Western research. The analysis takes a voice-centered approach

(Martin) and interweaves open coding (Bird et al.). Grounded theory provided

structure for an inductive process of analyzing the data that was grounded (Berg)

in personal reflections and assets from the game. This is similar to a

voice-centered approach that emphasizes giving participants the space to represent

themselves in their own ways (Bogdan & Biklen). I looked to Vizenor's ever

present poetics about survivance to inform the naming of codes that emerged

inductively. This approach calls for patience as the researcher waits for interpretations

and representations of patterns to emerge (Dana-Socco). In Indigenous research,

this also means including interpretations that emerge during dreams or as words

and images seen in day-to-day life. Between each phase of open coding, I dreamt

on the experiences of developing and playtesting We Sing for Healing. The patience needed when revisiting of We Sing for Healing thus felt parallel

to the development process and researcher-as-player experience.

Data visualization involves symbol-based reflection.

Anishinaabe symbol-based reflection, as described by Lynn Lavallée, is similar

to arts-based research that includes the making of art by the participants and/or

researchers as a pathway to understanding what we do within our practice (McNiff).

This method sits within participatory action research involving participants of

research in practical ways that empower people to contribute to both the

research and change within their community (Park). In regards to revisiting We Sing for Healing, the game is

presented as an act of survivance with symbol-based reflection visualizing the

design.

Scope and Significance

The

biskaabiiyang reflection of We Sing for

Healing which speaks to the development process and resulting game design benefits

game developers, researchers, and players interested in Indigenous game

development and Indigenous game design. Development techniques, design

mechanics, and narrative patterns can directly contribute to future Indigenous

games.

Notably, the journey of biskaabiiyang as a

researcher-participant is paralleled by the player in We Sing for Healing since they also venture, revisit, and transform

during gameplay. A robust follow-up study could be conducted with diverse

players to explore varying player experiences, identify self-determined

interpretations, and determine patterns such as the frequency of choosing

certain paths. Thus, the current research is intended as a grounding point for a

future player-centered study.

Development Process

We Sing for Healing's development process activates survivance as practice. The work is situated within the context of the digital divide, meaning the gap in Internet and technology access experienced by communities (Varma). The tools and resources used to develop and distribute the game were essentially no cost because they were either previously purchased at low cost or previously downloaded and available for free. The collaboration was reciprocal—the narrative journey and art were informed by Exquisite Ghost's music and vice versa. Thus, we both enacted survivance during creation and implementation of the game.

Both Exquisite Ghost and I were living in places with limited Internet when we started collaborating on We Sing for Healing. Our circumstances were different—I was living on land in a border town in Oregon that only had access to satellite Internet with speed and space limitations, while he was living in Winnipeg in the aftermath of a house fire. I too would later experience a fire that would leave me without a home and I would listen to his insight about not expecting the house to be rebuilt any time soon. This would propel me on a journey with very little in hand to the Great Lakes where I had only been in the summers and whose plant medicines and teachings came to me during youth thanks to my mother, my Auntie, and Anishinaabe elders living in Oregon. We Sing for Healing was a safe space to take risks in journeying, reflecting, and transforming before I went on a "real world" adventure. As I revisit the game now, I remember the incredible contentedness of only being responsible for caretaking honeybees and plants mixed with frustration about the lack of Internet access that put my ability to develop games into question. A text game with low bandwidth requirements came in part as a response to this divide I was experiencing as I simultaneously worked on the experimental animation "Returning." I encouraged myself: "I can make a game from anywhere."

But what kind of game? I had just finished designing and writing the board game The Gift of Food which was originally envisioned as a videogame but transformed into a board game because the community that the game was intended for lacked access to computers and Internet. The digital divide is a common experience for Indigenous communities and should be recognized and addressed by making sure the game that is being created with a community is truly about what meets their needs. At the heart of it all, I wanted to make a game that passes on teachings in ways that require players to either remember or seek out understanding within their own communities. Just as there are lessons woven in the mechanics as well as the symbols and materials in the art, Exquisite Ghost's music parallels my bitwork beadwork and digital demonstrations of flexible representation. The journey is the emphasis of the vision. The meaning is in the meaning the player makes. We Sing for Healing is a game that was made with and can be played with low bandwidth from a place where Google Maps can't zoom in beyond a brilliantly green arc of trees. It is a personal experience that relies on borrowed and open source tools. The open source tool Twine could have been a good fit to make an interactive story with some tweaks to allow embedded audio, but it didn't work for me the way I needed at the moment because I couldn't download it from home. My children were asleep and couldn't wait through the night to yet again drive during the day after so recently hanging around outside the public library to catch open wifi and download Exquisite Ghost's latest track remixed with my voice. Instead, I booted up a trial of Dreamweaver and began laying out pages as I listened. We Sing for Healing is an example of how anyone can create a game, from wherever they are, with whatever they have.

I've been taught to use every scrap of whatever I have and if I don't use it then I better save it for another moment. I had a laptop with Photoshop, paper, and markers. I had some Internet while sometimes Exquisite Ghost had none. Most notably, I had textures from experimental animations while Exquisite Ghost had an archive of previous mixes and snippets of sound from his origin album.

I also carried with me teachings to share in ways that would not be so explicit as to potentially risk storytelling and ceremonial protocol. In the spring before working on We Sing for Healing, Woodrow Morrison Jr. told me that we are at a critical point in where life is headed. Elders had gathered and determined that certain stories need to be shared for the better of all people, because if the spirit of consumption continues to eat and eat and eat, we will all be swallowed whole. Survivance pushes us to do more than simply survive, we are to thrive.

Thriving is dependent on self-expression in whatever form that may take, whether it be beading, weaving, painting, singing, cooking, or even sharing good words with others. Along my journey I had stopped using my voice because of a relationship that was a result of (but not to be excused by) historical trauma. I found my own strength again by talking excitedly about games in the context of Indigenous futurisms (Dillon) and imagining the potential of games created with Indigenously-determined technology. I was asked to record audio of an article I wrote for kimiwan zine that was included in a mixed tape by spacetime travelers Jarrett Martineau and Lindsay Cornum. Thanks to their work, I crossed paths online with Exquisite Ghost, who had contributed beats to the immense compilation. We shared a mutual interest in remixing—visual art in my case and music in his—as a form of survivance.

Thus kicked off many trips back and forth from the land to town where I would send Exquisite Ghost recordings of traditional and new songs I would sing mostly in Anishinaabemowin. He would remix audio and then offhandedly tell me where it was going to be played. Of course that it would be at a live public performance I had never imagined as a possibility. He was a trickster in this sense, one who helped me grow in my ability to not just sing publically but also to speak and share my perspectives overall.

Throughout the process, I would kick him some singing, he would kick me back a mix, and I would create art alongside poetic text and path choices informed by how the music resonated. The collaboration was truly reciprocal and ongoing, much like most of the paths in the game. We each inspired one another and discussed how to represent teachings about life, death, transformations, collective memories, naming, and spacetime through a musical text game.

Game Design and Aesthetics

"The ventures of

imagination, shadow remembrances, survivance hermeneutics, comic turns of

creation, tragic wisdom in the ruins of representation, transformations in

trickster stories, and individual visions, were one and the same..."

– Gerald Vizenor

We Sing for Healing is an act of survivance in design as much as in development process. As game designer Brenda Romero states and shows through her games, the mechanic is the message. The messages in We Sing for Healing are sometimes clear and sometimes "elusive, obscure, and imprecise" much like the definition of survivance itself (Vizenor 1). The music, art, and poetic phrases that make up the description and choices in the journey are left open to the interpretation of the player, much in the way Indigenous storytelling relies on the listener to create meaning as it may pertain to that moment while acknowledging that the interpretation is malleable and may change if a story is revisited at another point in life. We Sing for Healing speaks to survivance ranging from a broad look at the genre to specific mechanics including slowing down, listening, making choices, revisiting paths, and interpreting the journey.

At its core, We

Sing for Healing is played by visiting the website http://survivance.org/wesing/ and using single clicks to navigate through a non-linear

journey much like a choose-your-own adventure text game. Players are usually given

a range of text options on each webpage and reach the next webpage by clicking

on the linked text of their choice.

However, even in the genre description itself, We Sing for Healing entertains "vital irony" characteristic of survivance stories (Vizenor 1). The game purports itself to be a musical choose-your-own adventure text game, which ironically puts the focus on the game being about the music first and foremost while simultaneously using the term "text game" as a genre indicator. Text games typically focus on text, although tools such as Twine make it possible to embed images. From a code perspective, embedding audio in Twine is more complicated and invites a trickster playfulness into the game when people who are accustomed to Twine games assume that We Sing for Healing was made in Twine and initially puzzle over how there is music at all. The access-based choice to initially skip over Twine ended up allowing flexibility and self-determination to focus on music and generate a non-linear journey moment to moment rather than with a top down perspective of the narrative points referred to as nodes.

The game begins: "Breathe. Listen." The player is challenged to

physically slow down and more specifically to focus on the depth of their

breathing, which has been interpreted as a way to honor yourself as a player during

gameplay (Butet-Roch). Emphasis is placed on listening to the music, which

could result in experiences such as visualizing the game story or the player's

own story. This mechanic comes from land where I perceived spacetime to be

slowed because the day-to-day pace of life allowed me to do nothing but breathe

without any other thought. Now, living back in a city where there are work

hours to adhere to and deadlines to meet, revisiting We Sing for Healing reminds me of the importance of focusing on

breathing. In We Sing for Healing, survivance

as Native presence goes beyond merely referring to being an Indigenous text game

amongst text games. Rather, the fullness of survivance calls on us to be present.

Presence echoes our own interpretations back at

us as players in the game. In acts of survivance, "metaphors

create a sense of presence by imagination and natural reason" (Vizenor 13). One

path ends with the node "You are home in the space/time you create" alongside a

copper dragonfly against a copper background made of scratches created by sound

vibrations [Fig. 3]. Dragonflies are the ultimate spacetime travelers who have

transformed through many generations by constantly adapting. They are said to

be the carriers of the original songs. This could be seen as a metaphor referring

to their vibrational movement that has been continuous. From an Indigenous physics

perspective, dragonflies were present to pick up vibrations as far back as

origin frequencies up to traditional songs that they continue to echo today. The

teaching that unravels here is that presence, or the sensation of feeling home,

are intricately woven with understanding and balancing vibrations.

Figure 3. Copper Home, We Sing for Healing, 2015

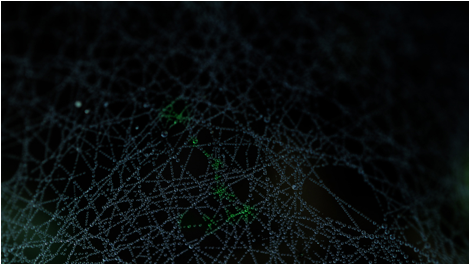

Along with presence, survivance stories "create a sense of... situational sentiments of chance" (Vizenor 11). We Sing for Healing first offers the player the choice to "listen, walk away, or look closer" [Fig. 4]. There is little indication of what might happen with any of the options, aside from what the player might guess from the presence of a web glistening with dew drops. They might assume there is a spider nearby, which would be a natural guess based on what happens in most games when a player chooses to get closer to a web, especially in the dark. However, Grandmother Spider, the weaver of stories, is away working on another part of the web of life and not overtly represented in the game. Instead, the journey takes players to space, to land, or to the height of a battle. The chances a player takes can be random. They can also be reflective of their interpretations and participation in being a storyteller in the game, which in turn furthers presence.

Figure 4. Web, We Sing for Healing, 2015

Regardless of the level of presence a player chooses during gameplay, the battle they are in the midst of in the game is one we also face in this reality. If the player chooses to look closer at the web, they see that "within, there is a world in battle as the notion of time as forward motion spins all imbalanced" [Fig. 5]. Teachings shared by Woodrow Morrison Jr. explain the differences in perceptions of time and spacetime beautifully. In Western perception, we are sitting in a canoe in the river of time. We can look behind us and in front of us, but we are always moving forward. In Indigenous perception, we walk alongside the river of spacetime. We can step in and out of the river at any point we choose. We are naturally and inherently spacetime travelers who walk dreams, stars, and dimensions. These teachings also accompany a warning. Linear thinking generates problematic structures of grabbing and taking rather than acceptance and gratitude, which continues to imbalance communities and risk all of our wellbeing. In alignment with Indigenous art of all forms, players in We Sing for Healing are encouraged to "[disrupt] colonialism's linear ordering of the world" (Martineau & Ritskes v).

Figure 5. Look, We Sing for Healing, 2015

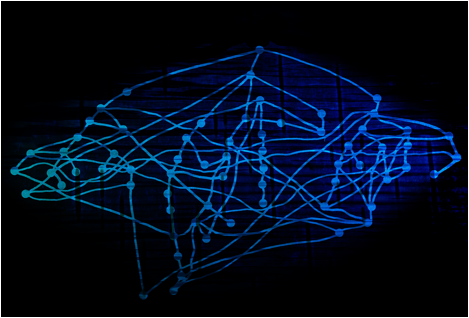

The journey in We Sing for Healing challenges linearity in story as well as design. Overall, non-linear paths in the choose-your-own-adventure style replicate traditional storytelling structures (King). Thus, the genre is a natural fit for an Indigenously-determined game structure. The various paths in We Sing for Healing reveal teachings, battles, self-reflection, trickster traps, and transformations, while the entirety of all paths combined embody their own form. Since the journey was made step by step rather than in a tool such as Twine that would show the structure during the development process, the design of the paths was entirely intrinsic and only seen so clearly thanks to revisiting the game for this research. Looking back at the various paths and outlining connections reveals that the fullness of the journey is, in and of itself, a turtle constellation [Fig. 6]. The lines show the connections between the story nodes. The wide view of the path options shows the arced back of a turtle. At the left is the turtle's head and at the right is its tail and claws pushing through water or space. Intersecting points reveal triangles throughout the narrative design from the inner center where the heart leads to shell lines to the front claws that propel movement.

Figure 6. Narrative Design of We Sing for Healing, 2016

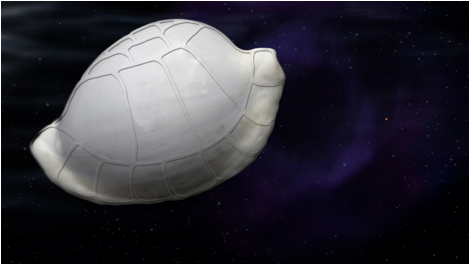

Notably, the node at the heart of the turtle represents a pair of thunderbird constellations looking over the world after following a central path where the player rides through space on a cowry turtle shell [Fig. 7]. Unlike any other path in We Sing for Healing, finding the turtle requires the player to engage directly by clicking on a stone formation stuck in tar sands oil. The player is gifted with seeing the turtle and adventuring through Turtle Island teachings. A geographically accurate top down view of Turtle Island, a.k.a. the Americas, reveals a turtle with one foot in the water. This form is echoed throughout teachings from physical land to perceptions of spacetime. The turtle shell includes thirteen inner scutes (moons or months) and twenty-eight outer scutes (days). Just as we stand on the back of Turtle Island, we also stand with the great turtle which is always in motion in space. With presence is ongoing movement and constant transformation, modeled for us by the great white sturgeon who continuously adapts.

Figure 7. Turtle Ride, We Sing for Healing, 2015

Enduring Presence

From game development process to design to aesthetics, We Sing for Healing is an act of survivance. Through an experimental process of collaboration followed by revisiting the work within the context of survivance implementing symbol-based reflection, I hope to expand awareness about the possibilities of Indigenous expression in digital games. The journey in We Sing for Healing opens pathways of story and spirals players to the heart of their choices. Whether or not the majority of players truly do slow down or follow through with paths is yet to be looked at in a study, but the existing reviews and researcher-designer reflection on the game development process and design offer insights.

We Sing for Healing calls on players slow down, listen, make choices, revisit paths, and reflect on their own worldview and relation to the teachings expressed and experienced during gameplay. I carry these lessons with me into the next works and hope to continue in ways that reflect the shimmers of survivance.

Works Cited

Berg, Bruce L. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences. Allyn and Bacon, 2001.

Bird, S., J. L. Wiles, L. Okalik, J. Kilabuk, and G. M. Egeland. "Methodological Consideration of Story Telling in Qualitative Research Involving Indigenous Peoples." Global Health Promotion Vol. 16 No. 4, 2009, pp.16-26.

Bogdan, Robert, and Sari Knopp. Biklen. Qualitative Research for Education: An Introduction to Theory and Methods. Allyn and Bacon, 1992.

Butet-Roch, Laurence. "In Praise of Slowness." Playing Indians, 10 April 2016, https://medium.com/playing-indians/in-praise-of-slowness-79281f13d8dc#.vbpg14r9y. Accessed 01 June 2016.

Byrd, Jodi. The Transit of Empire: Indigenous Critiques of Colonialism. U of Minnesota P, 2011. .

Caillois, Roger. Man, Play, and Games. Free Press of Glencoe, 1961.

Dana-Sacco, Gail. "The Indigenous Researcher as Individual and Collective." American Indian Quarterly, Vol. 34 No. 1, 2010, pp.61-82. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/370587. Accessed 2 June 2016.

Debassige, Brent. "Re-conceptualizing Anishinaabe Mino-Bimaadiziwin (the Good Life) as Research Methodology: A Spirit-Centered Way in Anishinaabe Research." Canadian Journal of Native Education Vol. 33 No. 1, 2010, pp.11-28.

Dillon, Grace L. Walking the Clouds: An Anthology of Indigenous Science Fiction. U of Arizona P, 2012.

E-Line Media. Never Alone/Kisima Ingitchuna. E-Line Media, 2014.

Elizabeth LaPensée. We Sing for Healing. Elizabeth LaPensée, 2015.

Goeman, Mishuana. Mark My Words: Native Women Mapping Our Nations. U of Minnesota P, 2013.

Gresczyk,

Richard A., Sr. "Language Warriors: Leaders in the Ojibwe Language

Revitalization Movement." Diss. U of Minnesota, 2011.

King, Thomas. The Truth About Stories: A Native Narrative. U of Minnesota P, 2003.

LaPensée, Elizabeth. kimiwan zine Issue 8: Indigenous Futurisms. Saskatoon: kimiwan zine, 2014.

LaPensée, Elizabeth. "Survivance Among Social Impact Games." Loading... The Journal of the Canadian Game Studies Association Vol. 8 No. 13, 2014, pp.43-60. http://journals.sfu.ca/loading/index.php/loading/article/view/141/171. Accessed 02 June 2016.

Lavallée, Lynn. F. "Practical Application of an Indigenous Research Framework and Two Qualitative Indigenous Research Methods: Sharing Circles and Anishnaabe Symbol-based Reflection. International Journal of Qualitative Methods Vol. 8 No. 1, 2009, pp.21- 40.

Lewis, Jason Edward and Fragnito, Skawennati. "Aboriginal Territories in Cyberspace." Cultural Survival Vol. 29 No. 2, 2005, http://www.culturalsurvival.org/ourpublications/csq/article/aboriginal-territories- cyberspace. Accessed 12 Nov. 2011.

Martineau, Jarrett and Lindsay Cornum. "Indigenous Futurisms Mixtape." SoundCloud. RMP.fm, 20 Nov. 2014, https://soundcloud.com/rpmfm/indigenous-futurisms-mixtape. Accessed 02 June 2016.

Martineau, Jarrett and Eric Ritskes. "Fugitive Indigeneity: Reclaiming the Terrain of Decolonial Struggle Through Indigenous Art." Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society Vol. 3 No. 1, 2014, pp.i-xii.

Macklin, Colleen and John Sharp. Games, Design and Play: A Detailed Approach to Iterative Game Design. Addison-Wesley, 2016.

McGonigal, Jane. Reality is Broken: Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World. Penguin Books, 2011.

McNiff, Shaun. Art-based Research. Jessica Kingsley, 1998.

Park,

Peter. Voices of Change: Participatory

Research in the United States and Canada. Bergin & Garvey, 1993.

Romero,

Brenda. "The Mechanic Is the Message." The Mechanic Is the Message. Brenda Romero, 7 May 2009, https://mechanicmessage.wordpress.com/.

Accessed 02 June 2016.

Seven Generations Education Institute. Anishinaabe Mino

Bimaadiziwin: Principles for Anishinaabe Education. http://www.7generations.org/testsite/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/AMB-Booklet-3.pdf.

Accessed 02 June 2016.

Simpson, Leanne R. "Anti-Colonial Strategies for the Recovery and Maintenance of Indigenous Knowledge." American Indian Quarterly, Vol. 28 No. 3&4, 2004, pp.373-85.

Simpson, Leanne. Dancing on Our Turtle's Back: Stories of Nishnaabeg Re-Creation, Resurgence and a New Emergence. Arbeiter Ring Publishing, 2011.

Simpson, Leanne. Lighting the Eighth Fire. Arbeiter Ring, 2008.

Shiwy, Freya. "Decolonizing the Technologies of Knowledge: Video and Indigenous Epistemology." Digital Decolonizations/Decolonizing the Digital Dossier, 2009, https://globalstudies.trinity.duke.edu/wp-content/uploads/2009/05/SCHIWY.DECOLONIZING.pdf. Accessed 01 June 2016.

Smith, Linda T. Decolonizing Methodologies. U of Otago P, 1999.

Todd, Loretta. "Aboriginal Narratives in Cyberspace." Immersed in Technology: Art and Virtual

Environments. Mary Anne Moser and Douglas MacLeod. Cambridge: The MIT Press,

1996, pp.179-194.

Varma, Roli. "Attracting Native

Americans to Computing." Communications

of the ACM Vol. 52 No. 8, 2009, pp.137-140, http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1536650&dl=ACM&coll=DL&CFID=624454555&CFTOKEN=79095579.

Accessed 01 June 2016.

Vizenor, Gerald Robert. Survivance: Narratives of Native Presence. U of Nebraska P, 2008.

Vizenor, Gerald Robert. Manifest Manners: Postindian Warriors of Survivance. Wesleyan UP, 1994.

Wilson, Shawn. Research Is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods. Fernwood Pub., 2008.

Zimmerman, Eric. "Narrative, Interactivity, Play, and Games: Four Naughty Concepts in Need of Discipline." First Person: New Media as Story, Performance, and Game. Ed. Noah Wardrip-Fruin and Pat Harrigan. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2006, pp.154-64.

Zimmerman, Eric. "Play as Research: The Iterative Design Process." Eric Zimmerman, 8 July 2003, http://ericzimmerman.com/files/texts/Iterative_Design.htm. Accessed 02 June 2016.