Ahkii:

A Woman is a Sovereign Land

GWENDOLYWN BENAWAY

Don't ask why of me

Don't

ask how of me

Don't

ask forever

Love

me, love me now

This

love of mine

had

no beginning

It

has no end

I was

an oak

Now

I'm a willow

Now I

can bend

-Buffy Sainte Marie, Until it's Time for You to Go

Author's Note: Waciye, Aaniin. I was asked to

write a creative non-fiction piece around my writing practice. I couldn't

imagine writing about my writing practice without writing about my relationship

to gender and land, so I have woven these threads together. As a poet, I'm

particularly interested in how Anishinaabe oral tradition moves between voices,

mediums, and narratives in order to create a space for questioning. This is my intention

within this piece, to not author truth but write a space where we can question

and explore as a broader community of Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples.

Miikwec, ka'kina awiiyaak.

Ahkii: A Woman is a Sovereign

Land

Gwendolywn (Mitikomis[i])

Benaway,

Makwaa doodem[ii],

Anishinaabe/ Métis, Niizh Ode[iii]

i walk on dirt roads

in a nowhere land.

it is deep night,

the middle of summer

inside dreams my bones

remember river water.

once we had names

no one can say.

the land and i

hold a soft wonder

between us

as I would lift

water to my lips,

dust and the smell

of lilacs is how

I taste in this sleep-

a girl hunts

her wholeness,

underground my gookum[iv]

dissolves to memory,

i will find her grave

in me soon.

a black bear follows me,

she watches as i

come back to

what I lost.

this is how ahkii[v]

finds me now,

by spaces in my body

she has not surrendered.

My early memories of my gookum's farmhouse are rooted

in the land. She lived at the end of an unpaved gravel road in Northern

Michigan. The land around her farmhouse was sparsely populated, filled with

giant stretches of bush, which seemed infinite. The boundary between the

farmhouse and the land outside felt fragile. The house leaned into the bush

during the day and the bush crept through open windows at night. I grew up

caught between fascination and a quiet terror of the bush around my gookum's

house. The wild in me has always warred with my desire to be safe.

My gookum kept a garden, planted with vegetables,

which never grew as expected. There were nightly incursions by foraging deers.

Snakes surrounded the house, often laying coiled in the pantry and traveling

through holes in the hallway to the bedroom. Several pairs of eagles nested

close by. My gookum left them scraps and waved whenever she saw them

flying. When I think of her and my

father's family, I think of that land. When I imagine myself as a child, I am

running through the back fields towards the dark border of the bush, alone and

boundless.

I hesitate to name my gookum as a traditional or a

non-traditional Anishinaabe woman. She was publicly Christian and prayed at her

kitchen table. She listened to polka music on the radio. She had diabetes and a

huge jar of pink Sweet n' Low packets. She walked her land every morning,

leaving bread, chunks of lard, and meat scraps behind her. Her favorite route

the trail beside the house, which ran towards the edge of the bush. On her

walk, she would pause and speak to every living thing she encountered. Was this

ceremony? Or simply her relationship to the place she was responsible for? Is

there a difference between these two acts?

She remains complicated for me. I witnessed her abuse

by my grandfather as a child. He would come home drunk and yell or hit her. We

know some of her children were by products of her rapes in their marriage bed.

She lived with him for most of her life until he died. She raised her children,

including my father, in an atmosphere of continual violence. I am the product

of the trauma, my father abusing me in a cycle that has flowed around my family

as long as I have stories of us. I feel she let me down, gifting all of her

children and grandchildren with her pain. She saved us also, working 3 jobs to

cover my grandfather's debts and feed my uncle, aunts, and father. She gave

love in balance to my grandfather's rage. She suffered while she triumphed.

Victim, hero, Anishinaabe woman.

I remember talking to an Anishinaabe elder about my

gookum. Like my grandmother, she had spent much of her life living in a very

abusive relationship. I asked her why she stayed, raising her children in the

middle of such violence. She answered me by speaking about how she tried to

protect her children, taking a majority of the violence on her own body. She laughed while telling me about how

her husband once broke a wooden broomstick over her back. "I must be some tough

woman to survive that, eh?" she said, lifting her left hand to cover her mouth

as she laughed. I've never forgotten what she said next because I felt like it

was the first time I could accept my gookum's choices. She looked directly in

my eyes, something we almost never do in Anishinaabe culture, and said "well,

in that time, there was nowhere to go. No one would help an Indian woman, so

you did what you had to do. I feel bad about what happened and what my kids

saw, but that's how it was". Anishinaabe women accept, Anishinaabe women laugh

in the face of violence. How long have we learned to survive on nothing?

When I remember my gookum, I don't think about the

violence I witnessed or the bruises on her face when we buried her. I see her

standing on the path to bush, whole in her blue floral apron. When I write, I

travel in my mind to my gookum and that land. This is one of the landscapes I

inhabit, the Great Lakes and the woods around our waters. One of the features

of my work is the central relationship of land and water imagery to my body and

sexuality. There are many reasons for my attachment to this particular

landscape, including race, relationship, and the foundational nature of my

childhood connection to it. For me, the strongest association between the land

and my writing is the complicated and metaphysical way which the land connects

to our bodies and spirits as Anishinaabe women.

~

I remember one of my elders teaching us the word for

vagina in Anishinaabemowim (Ojibwe). He cautioned us that any word for vagina

could never be used as an insult in Anishinaabe worldview. The word for vagina,

Ahkiitan, he told us while lighting up a third cigarette, comes from the word,

Ahkii, which means the land. Anishinaabe know that a woman is sacred because

she comes from this earth. She is rooted in. She carries it within her and like

the land sustains us, she sustains her community and family. This is why vagina

can never be an insult to Anishinaabe, because a woman is the heart of our

people. He continued on to tell us several different ways to insult people

using variations of the word penis, including my favorite, piijakaans or little

prick in English.

There are many gender-based teachings in my culture.

Anishinaabe worldview does not include notions of identity construction or even

free will. We come from creation. We carry responsibilities rooted in our

clans, our names, and the ceremonies we participate in. This includes our

gendered responsibilities as well. In the teachings I've heard, our spirits

choose the families we will be born into. I've always struggled with this

conception as an abuse survivor. My spirit chose to be abused? I'm not certain

I can accept that, but I do accept the concept that we came to this land from

spirit with specific responsibilities.

What are specific responsibilities I carry? Like all

Anishinaabe women, I have a responsibility to the land and it's waters to guard

their sacredness. I am meant to hold up the centre of my nation, to carry

language, culture, governance, and our systems of knowledge forward to future

generations. As a niizh ode woman, I am responsible to facilitate between men

and women in relationships and conflict, to protect and nurture other women

around me, and to hold my sacredness in all my relationships. I am a Bear Clan

woman, the ones who guard and protect our communities. We are supposed to be

fearless in our love. Brave, defiant, stubborn, ready to sound the alarm at the

first sign of danger. We call out violence within and without our communities.

We challenge people who hold power and we question oppression. We nurture

through plant and land medicines. We heal ourselves in private.

There is no way to separate my gender from my

responsibilities in Anishinaabe worldview. One gives birth to the other in an

infinite loop. Western culture is polarized between understandings of gender

that either root it as determined by biological "sex" or a more feminist

framing that sees gender as social performance. As a trans woman, I negotiate

these conflicting perspectives. Most people, regardless of their ideological

association, believe both of these viewpoints to some degree. I can be a woman

to them but a different kind of woman because of my body. I am eligible for

certain portions of femininity (activism, dress, expression) while denied

access to other portions (desirability, heterosexuality, socialization). It is

a complex landscape. No one tells me how they view my gender in explicit terms,

so I read their positions by their behavior towards me. Does the pronoun "she"

have an upper vocal inflection when they use it to describe me, as if they're

making mental effort to remember my gender? Do men respond to my body and

sexuality as if I am a woman or a man? How do the unspoken rules around my

gender present themselves in my daily conversations with friends?

My race is rarely factored into how people perceive my

gender. Because I am white passing (light skin, brown to blonde, blue eyes), I

am often erased as an Indigenous woman. In ways similar to my erasure as a woman,

I'm reduced to a lesser category of "Indianness". It's fine that I assert an

identity as an Indigenous woman to others, but they never factor matters of

race or history into their interactions with me. The public acceptance of my

race and gender contrasts the inner erasure of my race and gender. People won't

vocalize this discomfort or confusion because they don't want to wear the label

of racist or transphobe, so I can't challenge or question how I'm read. I can

only guess based on their responses.

This form of mind blindness, not knowing how I'm being

read or the borders of my believability as myself, is a pervasive violence. It

leaves me vulnerable to misreading people's responses to me as prejudice when

they may not be. It prevents me from undertaking the vital work of education

and engaging across difference. More importantly to this conversation, it

covers my life in a shroud of nothingness. What is a woman if she is never

touched nor seen? What am I if I have no language for my body? The tension of

living caught between the constant reality of harassment in public and the

careful neutrality of my intimate relations with friends and coworkers is the

most disempowering force in my life.

Of course, I know what I am. A woman, a traditional

and sometimes non-traditional Anishinaabe woman. What is missed in the

arguments for self love and internal validation of your gender is that social

agency is dependent on other human beings. My self-understanding matters, but

it doesn't grant me access to positive sexual and romantic relations, the

privilege to have meaningful engagements with other people where my gender and

race isn't invalidated, or the shared benefits of emotional and material

resources which come through relationships. Wholeness is shared and created in

relationships between bodies.

Inside Anishinaabe worldview, I am whole and free of

the contradictions of Western mentalities. Anishinaabe worldview does not exist

within the social space I navigate. My friends are mostly non-Indigenous. My

romantic partners are usually white men. I participate and engage within a

Western social context in a majority of my life. Anishinaabe worldview only

exists in little spaces within Toronto and across Ontario. We are cut off from

intellectual engagement with each other and the dominant thought systems. Even

within Anishinaabe spaces, trans women aren't always welcome. Western systems

of gender and sexuality assert themselves. The only place I am free is within

my writing. Within a conversation between land, my gookum and ancestors, and my

body, I sew myself together. A half-life, a second truth, working with the only

power I have, the same as every Indigenous woman I know.

We're the ones who hold the circle of our nations

together but no one holds us together as whole women. We're seen and loved in

pieces.

~

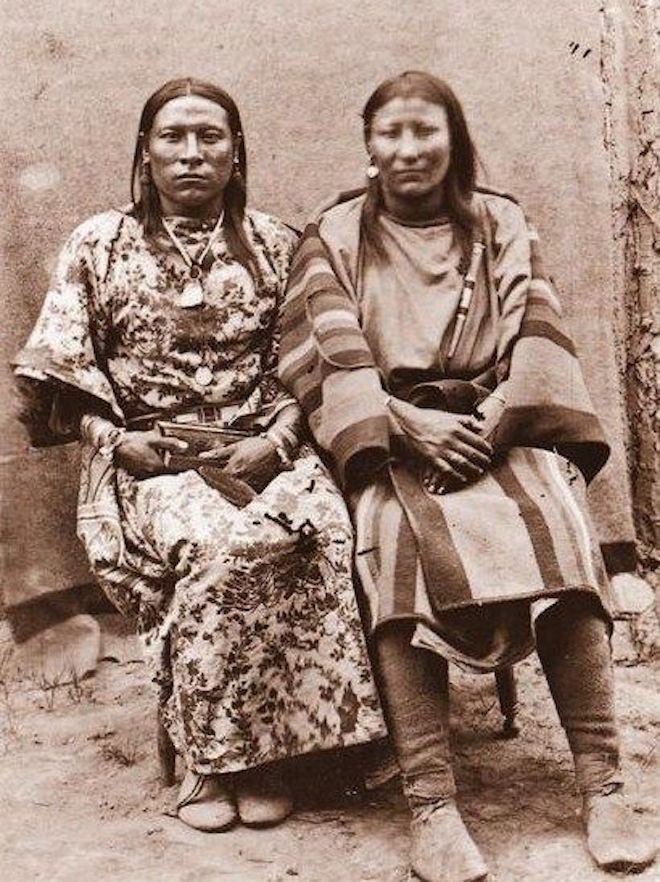

Two Spirit women, Cree, date

and subject unknown

wiindigo[vi] looks

for my heart

i'm hidden in

folds of land

i carry her

in my mind

a prayer

is longing

for this sweet

earth breaking

open in hands

like the budding

of my body,

I am here

and not here,

I am holy

and not holy

in equal measure.

to love is to know

loon call by

blood memory,

ancestors sing

at dusk to dawn

in every breath-

i breathe stars,

exhale truth.

this is a gift

to be born

inside two hearts

to believe in

the moon rising

as if I am

a heron lifting

up from clear water.

this is how ahkii[vii]

births me.

As a transgender 2 Spirit Anishinaabe woman, I do not

have a vagina yet. I plan on undergoing surgery to create one within my body in

the next 8 months, but in this moment, I am Ahkiitan less. In Anishinaabe

worldview, this does not negate my role as a woman. Often when we speak about

being 2 Spirited, we are talking about being gay or lesbian. My understanding

of the 2 Spirit teachings I've received are mainly focused on gender, not

sexuality. What we think of as trans women in the Western world seems like a

close parallel for conceptions of 2 Spirit in the Anishinaabe world of my

ancestors. We were born into male identified bodies, perceived by our grandmothers

as carrying a special set of responsibilities, and were raised from a young age

as women within our communities. We carried the responsibilities of any other

Anishinaabe women, but had some additional ones related to our unique

attributes.

We raised children who had lost their parents or kin.

We often worked for the community directly in a variety of roles, including

political and ceremonial. We usually had several husbands. We were the last

line of defense in our communities if we were attacked while our men were

hunting. We were celebrated as orators and storytellers. We cared for other

women during pregnancy and menstruation. Some ceremonies are centered around

our participation and leadership. We were as sacred as any Anishinaabe women

is. We did not have vaginas, but we always had our responsibility and

relationship to land.

~

One of my favourite traditional stories is about

Nanabush or Aayash, our first ancestor and the being who populates many of our

legends. He often reflects our humanity back to us, making mistakes or

illustrating worldviews though his behavior. Our stories are not moral parables

but were often recorded by Western anthropologists as such. They usually

stripped the sexual content from our legends due to their bias or discomfort.

The original stories, told through our worldview and language, are rich

depositories of knowledge and sites of inquiry. Storytelling was our version of

Anishinaabe university, the space we constructed and discussed the complex

frameworks of belief and insight.

In this story of Nanabush, he is wandering through the

bush when he sees a young Anishiinabe man in the distance. He finds the man

very desirable and decides to seek sexual contact with the man. To achieve this

desire, Nanabush feminizes himself, taking on the dress and mannerism of a

woman. He makes himself into the form of what he imagines the man will find

sexually pleasing. Once she is changed, Nanabush approaches the young man and

solicits him for sex. She is successful and after some foreplay, they begin

intercourse. Within the story, Nanabush participates as the receptive anal

partner to the man. She lets him penetrate her.

The story changes once the young man is penetrating

Nanabush. She finds the sex uncomfortable. She realizes this isn't what she

wants and for whatever reason, she becomes afraid of her sexual contact with

the man. She breaks away from him and runs off into the bush. She returns to

her male body as Nanabush. The story ends there and is often told in a humorous

structure. I have many questions about this story and what it illustrates about

my worldview.

Gender is performance in the story or a fluid state.

Nanabush moves between gendered embodied within the narrative. He alters his

gender in response to desire, becoming what he thinks the man wants. She

initiates sex very directly and her partner is responsive. There doesn't appear

to be any mismatch between their desires, but their sexual contact is still

relational to their bodies. Nanabush doesn't grow a vagina. It's highly

probable that she could, as a being of immense spiritual power, but she doesn't

need a vagina to elicit sexual desire in her partner.

Why does the story centre Nanabush's gender in

relation to sexuality and desire? What about her partner draws her to him? What

changes in her desire once she begins intercourse? Is the humor because she is

"crossdressing" or because she doesn't know what she wants? We can observe that

Anishinaabe worldview has different comforts with sex, about a woman initiating

sexual contact or about a man having sexual contact with a woman who possesses

a penis. Gender is clearly not rooted in biology in this story, but it does not

also position their sexual practice as homosexual. What's the lesson here? Is

it wrong to become a woman or that understanding what you desire is complex?

I don't think it's useful to look for simple moral

teachings from the story. The traditional use of stories was to generate

questions, not answers. The value is that it shows Nanabush, our most

significant legendary being who often represents us as Anishinaabe people,

moving between gender states and sexual practice. It is profoundly sex

positive. If Nanabush represents our ancestor, we are directly implicated in

her desire and sexuality. To Indigenous people who suggest transgender and same

sex relations are a Western corruption, Nanabush isn't a foreigner.

She is literally our humanity, questioning and

exploring herself within sexual practice and gender. I perceive the story as a

message coded within our worldview: yes, it is normal to question your gender,

to move between gendered expressions, to have desire and seek sexual

fulfillment, to decide what you thought you wanted is not what you want, to

experiment, to have sexual partners who possess bodies different from your

other sexual partners, and that anal sex is not something outside of our

culture. I also wonder if the story is a form of sexual education, a way of our

ancestors saying "hey if you're going to take a dick anally, it might be

painful the first time. Practice first?".

~

I have spent

half my life

denying the girl

I carry inside.

now I spend

my life being

denied as her,

double talk

wiindigo[viii] white boys think

I'm not whole,

tell what I'm worth,

half a woman

not meant to be

held like other girls,

here in the bush

I move like rivers

across a land

which wants

me as I am,

as close and deep

as starfall over

the spruce trees.

no one tells me

who I can be,

denies me

the love

I hold like breath

inside hollow bones.

windigo[ix] boys

can't hurt me

under the light

of my grandmother's moon,

nothing is denied,

no artificial boundaries

white boys make

around my body's land

can survive the wonder

of this new earth.

I am the girl

the wild made me.

ahkii desires me

as much as I desire her,

together we sing

this sky apane[x].

Colonization, Christianity, and Residential Schools

have eroded much, if not all, of our responsibilities and stories as

Anishinaabe trans women. We are the most vulnerable and stigmatized members of

our communities. 2 Spirit identified youth have the highest rates of suicide

and harm in our communities. We suffer unparalleled violence and are often

forced into sex work as a means of survival. I have never heard any Anishinaabe

public figure speak about transphobia or Anishinaabe trans women. Despite this

separation of culture and spirit, we remain holy.

While the Canadian government was stripping us of our

humanity and responsibilities as 2 Spirit Trans women, they were also stealing

and appropriating our traditional lands. We come from two distinct violations,

the degradation of our gender and the separation from our land. Like other

Anishinaabe women, we carry responsibilities for our waterways and stewardship

of our environment. When an Indigenous woman is forcibly relocated from her

land or denied basic governance of her territory, it is a spiritual rape of our

bodies. Land sovereignty is directly linked to body sovereignty. You cannot

break apart Anishinaabe womanhood from our land. We are connected by spirit

into a web of relationships, which stretches back through time to our first

ancestors. We carry those relations into the future in our bodies.

I lack the fundamental power to reclaim my lands. Most

of us as Anishinaabe women lack the fundamental power to reclaim our lands. The

Indian Act was designed to disenfranchise Indigenous women and their

descendants from traditional territories and community governance. We have been

caught in a cycle of violence, murder, and poverty for generations. We have

resisted in profound ways. We fought the government of Canada in court and

forced modifications to the Indian Act. Any moment of Indigenous resistance in

Canada and the United States has been fueled and powered by Indigenous women.

We broke academic barriers. We wrote books and made art. We forged new nations.

Still we suffer from a profound separation from our bodies and land.

This is why I write to and from my land. My writing is

a response to the violence I have experienced. I centre my body in my land. I

approach my sexuality and gender in the same way I used to run towards my

gookum's bush. I lean into my land by day and at night, my land leans into me.

The connection is not broken. My womanhood is whole. By situating my writing

and poetry within a bed of sweetgrass, I call my ancestors to me. This is not a

metaphor, but a daily practice.

One of the best pieces of writing advice I ever

received was from my elder. He looked at me and said "it's not wrong to long

for your ancestors". I take this as permission to reach back to them, to draw

them into my life and my work. Every time I write, I ask for help. This is not

like Joseph Boyden's recent claims to author his stories from the ancestral

voices in blood. I do not use my ancestors to deny responsibility. I am more

responsible because I write with and to them. It is not a refusal of my agency

as a writer, but embracing the ways I am situated in a profound set of

responsibilities and relations. I remember the same elder asking a group of

Anishinaabe youth what being Anishinaabe means. People had great answers about

our art, our spirituality, and our history as warriors. He waited until

everyone offered an opinion and replied, "To me, being Anishinaabe means being

responsible".

Writing is responsibility. Being an Anishinaabe woman

is responsibility. Being a trans Anishinaabe woman is a greater responsibility.

The land sits beneath me. I carry life within me. I am connected to the whole.

This is what makes Indigenous trans women sacred. Not our vaginas or our sexual

practice, but our relationships to our ancestors and the many diverse beings

who inhabit the world we walk in. One of the many things taken from us by state

violence is the understanding of our bodies as holy and the vital need for our

men to reflect that sacredness in their relationship to us.

~

I remember when I began my transition. I expected

difficulties, but I assume my natural resilience would overcome them. I trusted

in the relationships that populated my life. I naively believed that I knew

what would come as I went through hormone treatment and into my womanhood. I

didn't plan my transition as many other women I know did. I blurted out I was

transitioning in a staff meeting at work. A few days later, I announced it on

Facebook even though I had no idea what it meant for me. The day after I told

the wider public world my transition, I came home from work defeated. There was

a new intensity of fear around me, which I had never felt before. Was I making

the right decision? What would my life become? Did I want hormones knowing the

medical risks?

I walked into my apartment that day and lay on my bed.

I started crying, something I rarely do, and felt as far away from myself as

I've ever come. There was a sudden sense of presence in the room, a weight of

energy moving towards me. I had the sensation of women singing, a warmth which

enveloped me in the uncanny feeling of my gookum's personality. I don't frame

this as mystical experience in a Western sense, but in that moment, I knew I

was walking a path which my grandmothers had set before me since I was born.

Blood memory and spirit pulls me. This is my connection.

~

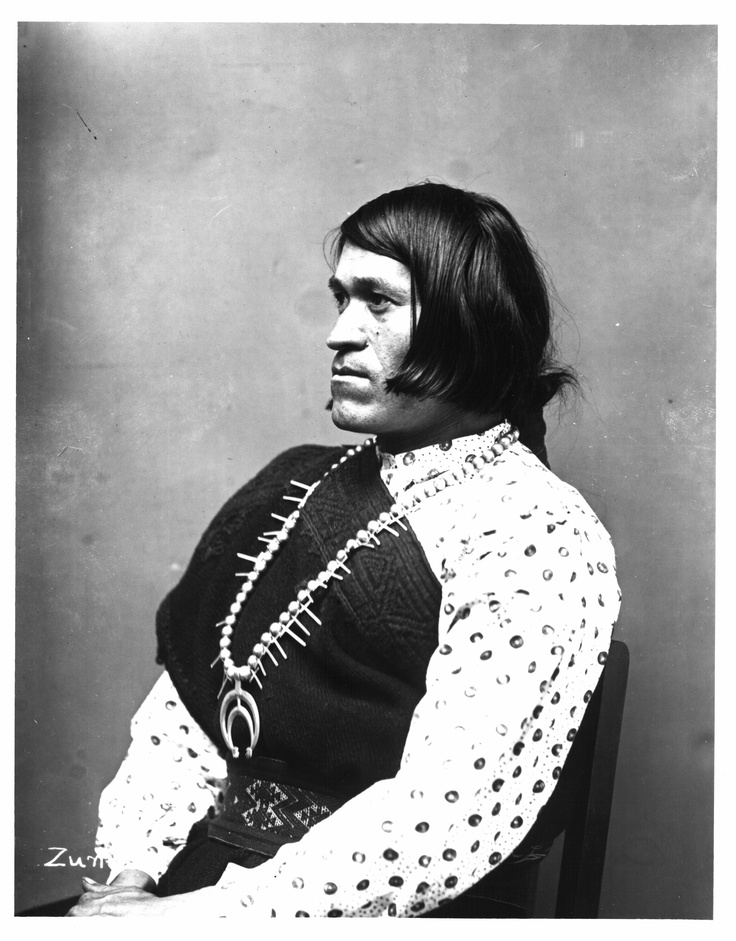

We'wha, Zuni 2 Spirit,

1849–1896

There are almost no visible Indigenous trans women in

the wider public. To my knowledge, I am one of the only published Indigenous

trans woman authors in North America. I know of two other Indigenous trans

women in the city I live in. All of us are disconnected in some way from our

communities, often moving in white or other racialized trans spaces without an

inherent recognition of our Indigenous nationship. The phrase 2 Spirit is

almost always applied to gay or lesbian Indigenous writers. They are well represented

in our literature and art. Recently, there was a special Indigenous centered

issue of a major Canadian literary magazine and none of the published writers

were transgender. Indigenous and transgender are not allowed to be connected in

our communities or in mainstream Canadian society. We are the invisible

descendants of the 2 Spirit women I only know through historical photographs.

I am enriched by the work of many gay and lesbian

Indigenous writers and thinkers. I am not arguing for their exclusion from the

label of 2 Spirit nor am I disputing the space they've built through their

activism. The work of 2 Spirit writers and artists is central to our

regeneration as Indigenous peoples, but so is the recognition of Indigenous

trans women. We need to remember that Western understandings of sexuality and

sexual practice do not define our understandings as Anishinaabe. Homosexuality

and heterosexuality are recent inventions of Western society rooted in economic

and social distinctions. We did not have the same framework for naming the

relationship between gender and sexual practice. The disruption of our cultures

and language makes it difficult to identify what our understandings were, but

there are some values that we know from oral tradition and Jesuit writings.

We did not have a system of monogamous marriage in

Anishinaabe culture. We had flexible extended family systems and often had

romantic triads. Sister wives, multiple husbands, a summer and a winter

partner, a relatively uncomplicated system of decoupling from romantic

partnerships, and ardent intolerance for sexual violence or abuse are some

characteristics of traditional Anishinaabe sexual and gender based relations.

We were perceived by Western audiences as immoral because of open and often public

sexual practice. We lived in very close proximity to each other and often with

several generations together. Sexuality was not seen as shameful, functioning

as key plot element of our traditional stories. In other words, our system of

sexual practices and relations did not bear much, if any, resemblance to

Western societies.

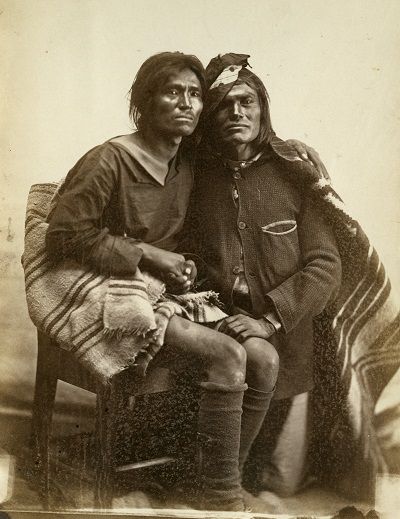

2 Spirit Women, Nation

and date unknown

Gender remains a more complicated facet of our

culture. We know through teachings and traditional stories that gender based

responsibilities were central to our governance and spirituality. Gender

appears to function separate from our physical bodies in Anishinaabe culture,

at least in regards to 2 Spirit women. We take on gender-based responsibilities

because of our spirits in Anishinaabe worldview, not our genitals. There is

agency involved and a wider community recognition of our unique embodiment.

From all the teachings I have heard in my life, 2 Spirit Anishinaabe women were

not perceived as different from other Anishinaabe women. We had the same

opportunities for sexual and romantic partners. We were not paired with other 2

Spirit women as our romantic partners, but men from within our communities.

What does this mean in terms of sexuality and gender in Anishinaabe culture? We weren't queer in a Western sense,

but naming what our role was complicated.

Why does it matter to identify a cultural framework

for 2 Spirit women in relation to contemporary transgender identity? It doesn't

to non-Indigenous people and perhaps to the wider Indigenous 2 Spirit

community. For women like me, embodied as Indigenous and transgender, it is an

attempt to connect the pieces of our identities into the bodies we currently

possess. I see my gender as an extension of my nation. My body is a literal

descendant of my Indigenous ancestors. How do I connect these parts of myself

within the heart of my culture without disconnecting myself from the land I

come from? Not possessing a language to name your gender and body is to be

dehumanized. This is what colonization has always sought to do to Indigenous

nations, to kill our ability to speak and understand ourselves within our own

worldviews.

This is the space I write to. I take the pieces of

culture and language I have and weave them into my writing. I hold my land

around me. In my mind, I see the 2 Spirit women before me, the ones I only know

through archival research and academic theorizing. Often they do not have

names. Often they are described by non-2 Spirit Indigenous writers or claimed

by gay or lesbian Indigenous communities. They look like the Indigenous trans

women I know. They have our faces, our complicated bodies, and above all else,

they have our souls. We know from historical records that the first ones killed

by the European invaders were 2 Spirit women. Out of the many aspects of

Indigenous nations that terrified them, we represented the deepest threat.

~

The most famous 2 Spirit Anishinaabe trans woman is

Ozaawindib or "Yellowhead". She is often represented by white and Indigenous

academics as a gay Anishinaabe man, but it's clear from the description of her

attributes that she was analogous to being a trans woman today. The language

used to describe her by the white observers is eerily similar to how many

transphobes describe trans women today, "one of those men who make themselves

women."[xi]

She was a war chief, responsible for leading incursions against rival

communities and defending her community. This is principally a male gendered

role in Anishinaabe community, so it is an interesting example of how complex

our traditional embodiments were. Why does no Indigenous scholar claim her as a

trans woman? It seems unusual to argue that transgender bodies are not part of

Anishinaabe worldviews by asserting that gay men are. Who are her descendants,

the gay men who identity and present as male or the trans woman who present as

female within society? She is as much our ancestors as theirs.

We know of her because she was romantically interested

in John Tanner, a white settler who writes about her in his diary. He is

apparently horrified and disgusted by her, claiming to reject her romantic

advances. Throughout the recorded details of their interaction, it becomes

clear that Tanner may be recording her as disgusting in order to placate his

sense of self about their likely romantic and sexual contact. In essence, the

most famous Anishinaabe trans woman in history is only known because of her

romantic engagement with a white man, a white man who goes to great length to

defame and deny his desire for her and their connection. I find this parallel

to modern narratives of trans dating and sexuality uncanny. How many times in

my romantic life have I been Ozaawindib, visible only through my partner's

public denial of my gender, desirability, and sexuality. They are ashamed to

love or sleep with us but drawn to our unique power. Holy, defiled.

When I look at the rates of murder and sexual violence

against Indigenous trans women in Canada, I see we still terrify them. I think

of how many times since I've transitioned that my life has been in danger. How

many times I've come close to rape. How many times someone has mocked me or

told me I'm not a real woman. How many times a man rejected my femininity as

real. The violence we are surrounded by is a direct extension of the violence

brought against our lands. When a society lacks a fundamental respect for women

and their bodies, they lose connection to respecting the world that sustains

us. Indigenous trans women stand in front of so much hate. Racism, sexism,

colonization, misogyny, transphobia, and homophobia define the scope and shape

of our lives.

~

How do we respond? How do we survive? More

importantly, how do we reclaim our bodies and relationship to creation? The

answer is returning to a profound love. As author Junot Diaz states in an

interview with the Boston Review (2012), "The

kind of love that I was interested in, that my characters long for intuitively,

is the only kind of love that could liberate them from that horrible legacy of

colonial violence. I am speaking about decolonial love". This is a conception

of love that resonates with me as an Indigenous trans women. I want to return

to a space in my intimate and sexual relations where my body is approached as

sacred and complete, where my Anishinaabe heart can rest with my partner's

whiteness and not be consumed, where the love I give and receive is open to

possibilities and my relationships are not defined by heterosexuality or

Western monogamy.

I like Leanne Simpson's simple framing of Decolonial

Love best in her poetic song about cultural reclamation, "under her always light".

She instructs her listener, "get two husbands and a wife. Make them insane with

good love". This is closest to the relational space I want to inhabit in my

body. If my body is holy as an Anishinaabe niizh ode, then I don't need to hide

the parts of my body that move outside Western binaries of being female. If my

love is an extension of creation, then it must be given freely to those in my

life without shame, jealousy, or price. If my sex and pleasure are celebrated

within my culture, then it is central to my wholeness. I can't change how

others see me, the lines of their erasure and desire, which write my body out

of the story of womanhood, but I can write myself into the world as sacred.

I see decolonial love as an answer to the separation

of Indigenous trans women from our communities and land. Much of the burden of

living within this body is rooted in fundamental absence of love, which

surrounds me. When I transitioned, I realized no one touched me anymore. Soon

after starting hormones, I stopped having sex with men because I felt a

pervasive othering of my body in sexual relations. I feel the violence of

desirability as an intimate weapon. Sometimes it overwhelms me. Sometimes I

long for a love that is given freely, that I don't earn through my gender

performance or the fetishization of my body. I want to be free from a world that

doesn't see or value me, so I build within myself a lodge of my culture, a

space where the words and hostility directed at me is met with a fierce love. I

imagine Makwaa embracing me. I seek every small love in any opening in the

borders of whiteness and gender I can find. This is what my ancestors taught me

to do, surviving for generations in a cold and changing land by being adaptable

and brave.

A decolonial love flows from creation and through the

land to our bodies. This is not a platitude but a spiritual reality. In

Anishinaabe culture, an orphaned child is considered very powerful. Because

they have been severed from their kin relations, the spirits come closer to them.

The land reaches out as our original mother to hold them up. I think the same

relationship exists for Indigenous trans women. Severed from our community

role, in danger and under attack, the ancestors walk with us. Our land responds

to our need. We become more holy in our pain, not less.

This what I work to do in my writing. Author us as

Indigenous trans women as powerful and connected to creation. Write over the

slurs and shame surrounding our bodies. Transmit what I know of my culture and

our value into words to carry across the land. Reconnect us back to where we

come from. Imagine our lives as filled with love and trust. Challenge and

question masculinity, threaten Western conceptions of sexuality and gender, and

demand our communities stand with us. Lee Maracle, a celebrated Sto'lo author,

says that Indigenous poetry is prayer. I am praying in every line I write.

In ceremony, we name the forces of creation and call

those beings to sit with us. Every poem is a ceremony. Every image of land is a

request for those ones to join us again. I write the way back to my gookum's

farmhouse. I am longing for my ancestors. My life is difficult, but I am not

broken in this work because I carry the waters of my grandmothers with me. I

imagine a new future for my people, a space where we return to our bodies as

whole beings. I see us standing together, interwoven with stars and cedar, as a

vibrant circle of light around this land. This is not mythology, but prophecy.

I come back

to every bush

I've lost,

as if promise

is my destiny,

as if nothing

they have done

is great enough

to take this

woman

from me,

she rests

in kiizhik[xii] groves,

she dreams

her spirit

home.

she dreams

all our spirits

through lakes

inside storms

she is singing

and the sound

of her voice

travels to echo

in me as if

I am the shape

of her entire dreaming.

~

I remember an elder telling me I was contaminated. He looked

at my blue eyes and said I was infected by the enemy. This is how I often feel

as a trans woman. Filthy, corrupted, inviolate, a woman who hides a sickness.

When I'm intimate with men, I often try to hide the parts of my body which

don't conform to what they expect of a woman. I am paying a surgeon to erase

the male parts of my face. I'm training my voice to fall into female ranges.

This fall, I will be booking a surgery date to change my genitals. I never told

any of my casual partners that I was native. I let them assume whiteness. I

pretend to be always female.

Of course, I used to be a man. Of course, I am Anishinaabe.

Who we are is often who we are allowed to be. I keep the dangerous parts of me

a secret. I learned men's medicines from many of the elders I worked with. For

several years, I was a regular firekeeper, making and maintaining the sacred

fire which sits at centre of many of our ceremonies. I moved through the world

of men without ever feeling part of them. I still hold both parts of me

somewhere.

I learned quickly in my transition that any signs of

masculinity would erase you to the world. Display masculinity in any context as

a trans woman and you will be thought of as a pervert. I have to always be

feminine or risk retribution and shame. I remember wearing a sweatshirt to work

one day. A female coworker stopped me in the hall and said "Well you don't look

very feminine today, do you?". Her scorn followed me for weeks. I realized the

only way to be desirable to my male partners was to inhabit my femininity as

deeply as I could. Hide what couldn't yet be changed, disguise what wasn't

right. Highlight my eyes to draw attention away from my nose.

This is where Anishinaabe worldviews differs from Western

understandings of being a trans women. 2 Spirit women were allowed to pick up

male medicines and responsibilities when they chose to. Sometimes, we picked them

up because there was no men around and it was needed. If our women and children

were attacked when the men were away hunting, it was the 2 Spirit women who

went first to battle against the invaders. We needed to know both sides of

gender, to kill and to give life. I have some of him in me still, as much as he

feels like someone I knew a long time ago.

I find this imbalance relational to my perceived whiteness.

I am read as white by the world so I hide the Anishinaabe in me. Other half

breed women have tricks to make their race visible, beaded jewelry, dying their

hair black, or heavy black eyeliner. I've watched these racial modifications

play out in many ways. Sometimes pride, sometimes shame. How similar am I in my

transness? Playing with presentation, looking for way to blend in. Do you

celebrate your unique humanity or carefully disguise the parts no one wants?

I find my body fascinating in its current state. I like the

shifts between male and female in its form. A woman's breasts, a man's ribcage,

a woman's hips, a man's penis. There is something soft in my body. There is

something hard in my body. I am both, leaning slowly towards the feminine but

holding on to the masculine. Why is this not beautiful? Why is this not

desirable? Why must everything be simple for white people to value it? Why

can't I be as complicated my 2 Spirit ancestors? Why do I have erase myself in

order for men to see me as real? I miss Anishinaabe worldview. I am

contaminated, but not by my white ancestor's skin colour or eyes. I am infected

by their dreams, what they are willing to embrace.

I imagine a love where I am a girl who becomes a boy when

she wants to. I imagine a love where I am an Anishinaabe who takes the parts of

whiteness which are useful. I refuse to be loved in pieces. I am already

whole.

~

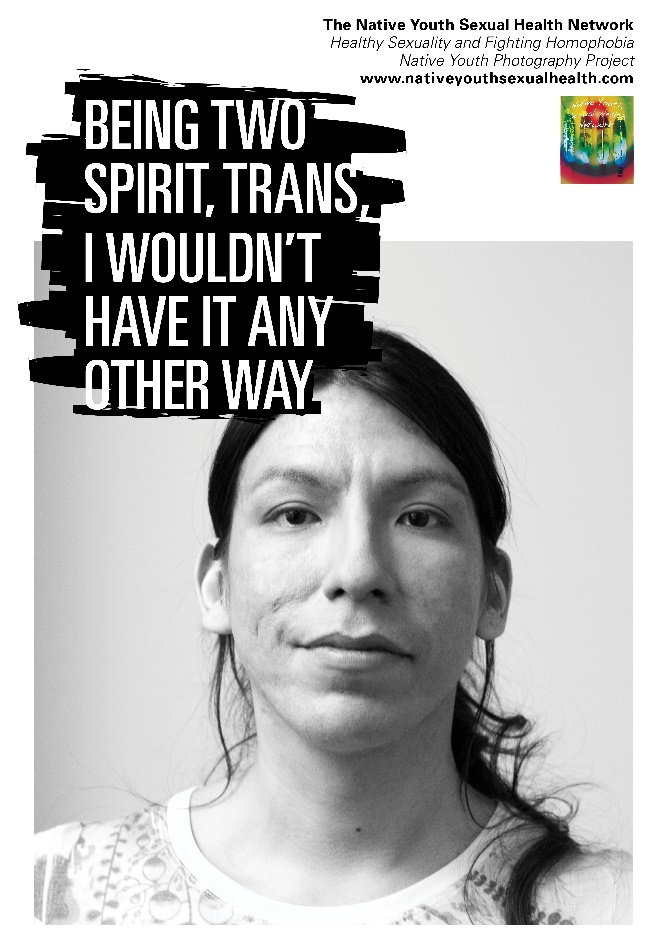

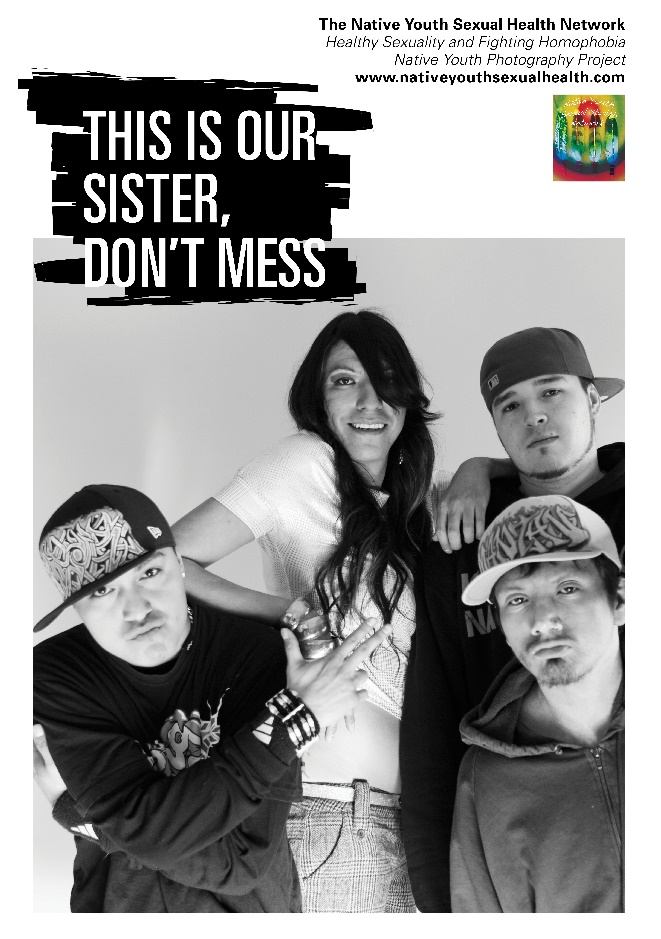

2 Spirit/ Trans educational

posters, Native Youth Sexual Health Network, Toronto

When I received my Anishinaabe name,

I was wearing long floral dress. I was introduced to creation as a woman. This

is one part of my identity, which has not changed since I transitioned. I

remember my gookum teaching me to make bread in her kitchen. She did not make

go outside to play with my male cousins. She let me stay with her, learning the

borders of her world. We never spoke of it before she died, but I think she

knew what I was before anyone else did. I come to my body through her body. I

pass through every woman in my family to return to myself. This is what is

sacred in me.

There many fears and misunderstandings of what it is

to be a trans woman. Everyone I meet carries some of these misconceptions. I

often feel like an educator, explaining and naming my body to the world.

Despite the increased visibility, we are not known as ourselves to the wider

world. Similar to how the non-Indigenous world mythologizes Indigenous peoples

as savage and primordial, trans women are demonized and misunderstood by the

cis world we walk in. To live between both of these erasures, as a woman and as

an Indigenous citizen, is a strange and lonely path. Being Indigenous separates

me from the non-Indigenous world and being trans often separates me from the

Indigenous world.

One of the great traumas of colonization is the

separation of Indigenous peoples from our worldviews. By breaking apart our

families and repressing our languages, colonization deprived us of our

intellectual inheritance from our ancestors. My ancestors spent thousands of

years learning and theorizing what gender and sexuality meant to them. They

built profound systems of kinship and sexual practice designed to create loving

and health family units. They must have made mistakes as well, insights we

could have learned from now. I cannot reconnect all of the threads which have

been severed.

My elder told us that nothing is lost. To him, our

languages and worldviews were living beings that inhabited a space separate

from time. He wasn't worried about appropriation or language loss. I remember

him saying, "If Anishinaabe needs those things, they only need to ask for them

and they'll be here". At the time, I didn't believe him. Now, having walked

through this transition to come back to myself, I understand the power in

seeking wholeness. When you ask, they answer. We need to, as Indigenous writers

and communities, ask for those 2 Spirit teachings to return to us. We need to

find new ways to form romantic and sexual bonds between and within our genders.

We must hold up Indigenous trans women if we are to come back to ourselves.

In the heart of my writing, I am standing on a

lakeshore watching a heron dive. I am walking through a low brush of cedars by

a swamp bank. I am drifting through an estuary towards a wide muskeg. I am

standing in the dark of spruce trees in winter. I am building a lodge out of

willow branches. I am peeling layers of birch bark off my skin. I placing tobacco alongside a river

while thunders move overhead. This is not mystical. This is not imagining a

spiritual destiny. This is the only way I know to be a woman: on my land, in my

waters, through my grandmothers, working on behalf of my relations, and

sustaining my worldview one metaphor at a time. This has always been the

responsibility of an Anishinaabe 2 Spirit woman. I am responsible.

some day

I will return

to the land

I carry.

some day

my sisters

the murdered

the raped

all of us

Indian women

will return

to the holy earth.

until then

I sleep inside

the softness

of my land

I will speak

us whole,

kill wiindigo[xiii]

with truth,

be a girl rooted

in ahkii[xiv] like

an oak tree.

Acknowledgement:

I am grateful to the Anishinaabe

elders, traditional knowledge keepers, and 2 Spirit women who have passed these

teachings onto to future generations. I am especially grateful to Alex Mckay,

Doug Williams, Shirley Williams, Edna Manitowabi, and Pauline Shirt. Any

mistakes in language or representation are mine. All interpretations are a

reflection of my own learnings and perspective, not a definitive guide for all

Indigenous nations or even other Anishinaabe people. I likely get as much wrong

as I get it right, but I think it's important for us to as Indigenous peoples

to work collectively to revitalize our narratives of gender, sexuality, and relationships. I am also grateful to the work of

Leanne Simpson in this regard.

I am also grateful to Wesley Brunson

(University of Toronto, M.A Candidate in Anthropology, Zhaaganash, Minnesota)

for his help in the development of this work and his editorial feedback.