creation stories: survivance, sovereignty,

and oil in MHA country

STEPHEN ANDREWS

Berthold

before Bakken, and Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara before Berthold. Before Tribe, there was river and sea,

and before water the back information of Time that shapes the meaning of this or

any other narrative.

It is January 2013, and

snowfall is beginning to thicken as these thoughts congeal into notes. Just returned from the first of several

interviews I was granted permission by MHA administrators to conduct, I am

awaiting a cheeseburger at the Wrangler Café in Parshall, North Dakota, home of

the Braves, located just on the eastern edge of its namesake oil field, which

was discovered in 2006 by EOG Resources in conjunction with consulting

geologist Mike Johnson.[1] Commentators

on the history of the Bakken boom point to the discovery of the Parshall Field

as the "eureka" moment that for oil investors and lease operators alike

transformed the Bakken from enormous potential to immediate "play." By the time

my burger arrives, seven years later, so to speak, I've already heard whispers

of another taking. Not the land outright, as in 1949, but a swindle of mineral

and drilling rights to the tune of nearly a billion dollars. The

more things change...

It

is 1943, and flooding along the lower Missouri has "caused billions of dollars

in damage and flooded thousands of farms in Nebraska and Iowa." After nearly "a

century of catastrophic flooding," the floods of '43 are a tipping point that

triggers a call for a massive engineering project to build a series of dams

across the upstream portions of the Missouri and tame the Big Muddy

(VanDevelder 26). The Pick-Sloan Plan, according to namesakes Colonel Lewis

Pick, of the Army Corps of Engineers, and Glenn Sloan, of the Bureau of

Reclamation, will provide access to irrigation for "four million acres of bone

dry prairie" upstream while ensuring flood control to downstream farmers in

Iowa and Nebraska (27). The "jewel in the crown" of the Pick-Sloan Plan will be

the Garrison Dam, set to be located in the heart of Mandan, Hidatsa, and

Arikara country. Once the dam is completed, the symbolic and economic heartland

of the Three Affiliated Tribes of the Forth Berthold Reservation, an area that

includes the tribal headquarters at Elbowoods, will be submerged under "a six

hundred square-mile lake." The Tribes will lose 153,000 acres of bottom land

that has some of the richest topsoil in the world—18 feet deep in some

places, according to Cory Spotted Bear—and many will be forced to attempt

farming and ranching on the less arable "bad" lands west of the river.[2]

The Tribes, with help from Wyoming Senator Joseph O'Mahoney, fight valiantly

for four years to "forestall" what Paul VanDevelder refers to as an "inevitable

catastrophe" (28). On October 9, 1945, during Congressional hearings on the

matter, Senator William "Wild Bill" Langer of North Dakota asks the Chairman of

the Three Affiliated Tribes, Martin Cross, how long his ancestors had been

living in the area in question. "Since time immemorial," the Chairman replies

(117-18). Given that answer, what could possibly constitute ground of equal

value or the price of "just compensation?" By then, though, all involved know

too well that relocation to acreage of equal value would not be forthcoming in

a Plan that has all the earmarks of a fait accompli in which the cultural and

economic well-being of the Tribes seems a mere and increasingly irritating

afterthought. Built to accommodate the submergences and dislocations of what

the Elders would thereafter refer to as "the Flood," New Town, located on

Highway 23 some 70 miles northwest of Elbowoods and twelve miles west of

Parshall, will be established as the new tribal center as of 1951.[3]

As if in cruel mockery of the immemorial "heart" of Tribal life now lying

submerged under the waters over Elbowoods, New Town is about as far north as

one can go and still be on the Reservation. But at least it was dry.

Several other tribes

along the Missouri, including the Sioux, were traumatized by the effects of the

Pick-Sloan Plan. But as Michael L. Lawson points out, "the most devastating

effects suffered by a single reservation were experienced by the Three

Affiliated Tribes whose tribal life was almost totally destroyed by the army's

Garrison Dam" (29). Recently, in December of 2016, MHA Chairman Mark Fox highlighted

the irony of these tragic events in commemorating the restoration of nearly

25,000 acres that had hitherto been under the control of the Corps of

Engineers. "Half of our adult men were fighting for their country and

their homes in World War II when the federal government began making plans to

take our lands for the Garrison Dam," Fox said. "The flood caused by the Dam

displaced 90 percent of our people from their homes. It literally destroyed our

heartland" ("Interior Department"). The legal basis of such action, referred to

by the government as a "taking," can be found in Amendment V of the

Constitution: "'nor shall private property be taken for public use, without

just compensation." "Just

compensation," unlike beauty, is not in the eye of the beholder so much as in

the pen of the colonizing power, in this case represented by the Army and the

Bureau of Reclamation, both working on behalf of descendants of settlers rather

than in the best interests of the Tribes. As if to underscore this point,

amateur historian and blogger Judi Heit points out that "the Corps of Engineers, without

authorization from Congress, altered the project's specifications in order to

protect Williston, North Dakota, and to prevent interference with the Bureau of

Reclamation irrigation projects. However, nothing was done to safeguard Mandan,

Hidatsa or Arikara/Sahnish communities" ("Ghost Lakes"). Do I need to add that

Williston is not on the Reservation and that the majority of its residents were

white? When

all was said and done, according to legal scholar Raymond Cross, son of the

aforementioned Martin Cross, "just compensation" for the Fort Berthold Taking

Act (Public Law 437), signed into law by President Truman on October 29, 1949,

turned out to be 7.5 million dollars—a paltry sum indeed for land on

which the people had been living since "time immemorial."[4]

"Just compensation," then, turns out to be just compensation, just one more turn of the colonizer's screw, and

hardly surprising at that.

Colonization," according to Elizabeth Cook-Lynn, "is not just the invasion and inhabiting of a place owned by others; it is the setting up of laws to legitimize the power of occupancy and ownership" (2012 138). As an example of the kind of legitimizing she has in mind, Cook-Lynn points to this same "mid-twentieth-century Missouri River project, which, through federal law, destroyed millions of acres of treaty-protected land for hydropower over the objections of the citizens who lived there" (138). For Cook-Lynn, herself a member of the Crow Creek Sioux Nation that was also adversely impacted by the Pick Sloan Project, the social goods of cheaper power, accessible irrigation and effective flood control are each a metonym for a history of Native eliminationism in the name of social progress. As such, these "goods" will not be allowed to blunt the urgencies of her central and abiding question: "for how long will the courts and academia and the intelligentsia of this country refuse to describe this history as genocide?" (68 emphasis in original). As a means of pointing out the ramifications of that history, Scott Richard Lyons makes a useful distinction between "migration" and "removal." Lyons imagines that migration has a "value" akin to what "Gerald Vizenor has called transmotion: a 'sense of native motion and an active presence,' that is recognized by 'survivance, a reciprocal use of nature, not a monotheistic, territorial sovereignty'" (5). Removal, Lyons later states, "was a federal policy established in 1830 by President Andrew Jackson, and it would now go by the name of ethnic cleansing" ("Introduction" 8, emphasis added). Not only would it go by that name now, but as Cook-Lynn reminds us, "[o]n Indian reservations even today the writing and enforcement of the laws of colonization are always charted by the federal system, often without the consent of the governed" (138 emphasis added). Even today—pipelines and competing jurisdictions crisscross Indian Country and undercut the very idea of sovereignty.

In October of 2013, Lisa

DeVille and her husband, Walter, gave me a tour of the oilfields along an

unpaved BIA road in the Mandaree area, where

Fig. 2a

Fig. 2 the artificial palm trees are located at top left corner of this mini-man-camp.

Fig. 3 Where fracking is concerned, there is no oil without water In what will turn out to be an even greater irony than

the oil itself, the water of Lake Sakakawea, beneath which lies the Tribal

heartland, will be even more valuable than the oil.[6]

From Fox's perspective, MHA will have gone from what Raymond Cross, borrowing

from Bonnie Duran, calls the debilitating effects of "intergenerational

post-traumatic stress disorder" (Cross 2000, 958), a disorder underscored for

his generation by a righteous rhetoric of too much water and not enough solid

land, to a post-oil future in which MHA, facing West, will have surplus water

for a world that cannot get enough of it. "One day," Fox says by way of

emphasizing his point, "in this nation and in this world, a barrel of potable

drinking water is going to be more valuable than a barrel of oil." All the more

reason, then, to minimize wastewater contamination, which may turn out to be

easier said than done. According to a 2016 Duke University report, "there have

been approximately 3900 brine spills reported to the North Dakota Department of

Health by well operators." The report goes on to define "brine spills" as "the

accidental release of brine that may potentially impact groundwater or surface

water" (Lauer). The key words here are "accidental" and "reported," since both the

DeVilles and the aforementioned Tribal Business Council member, Cory Spotted

Bear (Twin Buttes Segment), are convinced that there are occurrences of illegal

dumping. Illegal dumping, while pernicious in its cumulative effects, may turn

out to be the least of their worries. On July 8, 2014, a

leak in Crestwood Midstream's Arrow Pipeline "dumped more than 1 million

gallons of brine and oil in a Mandaree tributary of the colossal lake formed by

the Garrison Dam" (Nauman). That "colossal lake" is what Fox is envisioning as

a liquid lock box for MHA's future. Moving

forward, as with looking back, the problem that the oversight of environmental

hazards presents is that so much is out of the direct control of MHA. In what

follows, I will trace out the implications for Tribal sovereignty as it

pertains to the aspirations of two MHA members—Lisa DeVille and Cory Spotted

Bear—both of whom I interviewed in the summer and fall of 2013. In doing

so, I will elaborate on and interweave four different types of creation

stories: the tale told by oil which, like the immemorial past of the MHA

people, is a resource buried under the weight of its own history; the

aspirational stories told by Spotted Bear and DeVille and the examples they embody

that take sustenance from that deep past in

order to progress toward a workable and sustainable future; the critique of

the dominant culture's political creation story as elaborated by Raymond Cross,

a legal scholar for whom the founding of a doubled America—"one Indian

and one non-Indian" (Cross 2004, 61)—might now, in a post-boom world,

become an opportunity for renegotiating "the existing civil compact between the

Indian and non-Indian peoples" under the aegis of what he calls, following

Charles Taylor and Clifford Geertz, "'deep diversity'" (64). These creation

stories will themselves be served by another type of creation story, the

writer's peculiar form of re-creation which we have come to call the essay. I.

Essay/assay: the first doubling All stories, according

to self-described "postindian ironist," Gerald Vizenor, are creation

stories—none more so than that late arrival, the essay. Merging the

neo-pragmatist critique of Richard Rorty with his own critique of the logic of

Manifest Destiny that he calls "manifest manners," Vizenor goes on to say that

"[t]he shadows in trickster stories would overturn the terminal vernacular of

manifest manners, and the final vocabularies of dominance" ("Shadow" 68). For "native stories," as Vizenor

explains in "Penenative Rumors," "are the canons of survivance: the tease of seasons, scent of cedar,

oneric names, shamanic creases, and the transmotion of sovereignty" (23). He

might as well have said "canyons," where the tease of natural reason sent by

cedars and the twists and turns of elemental forces over time have creased the

very landscape of selves that are decidedly "not... essence, or immanence," but

are instead "the mien of stories" (20). Quoting literary theorist David

Carroll, Vizenor is careful to emphasize that "master narratives"—the

upper case Creation Stories of manifest manners and final

vocabularies—"perpetuate an injustice" in their "denial of the right to

respond, to invent, to deviate from the norm" (27). Such deviations—which

I take to be synonymous with Vizenor's notion of mien—are definitive, if necessarily diffuse, as implied in

the following Vizenor quote from Jean François Lyotard's "Lessons in Paganism":

"the people does [sic] not exist

as a subject but as a mass of millions of insignificant and serious little

stories that sometimes let themselves be collected together to constitute big

stories and sometimes disperse into digressive elements" ("Shadow" 68). That

key word "mien," then, which figures as attitude and affect, is a sign of presence

and belongs neither to teller nor auditor but links them both to the

contingencies of the story being narrated. As

Vizenor suggests, every story impels many miens and no single story speaks for

the order of things. Since "[t]he native essay is the transmotion of nature,

culture, and sovereignty," the stakes, as Vizenor sees them in "Penenative

Rumors," are high indeed (25). In what amounts to an essay on essays, Vizenor

takes pains to point out the multifarious "miens" of the essay form. It is, he says,

"resistance," "contention," "mediation," "venture," and above all

"contingency"; it is also a "tease of creation" as well as a "trace of

survivance and sovereignty" (23-4). As if to underscore that the essay is

ultimately in the service of something larger than itself, Vizenor switches

from indicative to imperative mood: "The essay must tease creation," and "[t]he tease must reverse modernist

theses, models of the social sciences, and the narratives of a native absence

as an indian presence" (23, emphases

in original). In Vizenor's hands, the essay is the medium that best expresses

his sense that "the eternal tease is chance" (Postindian Conversations 19). "Chance," as I understand it, teases

us in the form of contingency, and provokes us in the form of risk. From that

perspective, Vizenor's notion of the essay is very much in line with that of

Michel de Montaigne, who is generally credited with being the inventor of the

modern essay. For Montaigne, the essay ushers forth "a new figure—an

unpremeditated and accidental philosopher" ("Apology"). Philosopher Ann Hartle

opposes "accidental philosophy" to what she calls "deliberate philosophy." The

former, being "nonauthoritative" (34), seeks not to "aim at a preconceived

conclusion" but instead follows a path "of discovery that allows the accidental

'some authority'" (87). Deliberate philosophy, Hartle stresses, seeks nothing

less than "divine stasis," as in

Plato's "eternal forms" or Aristotle's "first causes" (27) or in the implied

teleology of manifest destiny. With its reliance on the logical forms of "the

syllogism, the disputation, and the treatise," deliberate philosophy "assumes

the truth of one's premises," and so "aims at a predetermined conclusion" (87).

We can see that the protocols of deliberate philosophy are very much in line

with those of what Vizenor calls "modernist theses" and "models of the social

sciences." As he explains in Native

Liberty, "I write to creation not closure, to the treat of trickster

stories over monotheism, linear causality, and victimry" (6). The task of his project, then, is to

figure out how to restore "some authority" to the ongoing traces of "survivance

and sovereignty," traces that are constantly under threat of sedimentation by

the deliberative discursive pressures brought to bear by 500-plus years of

"accidental" indianness. Here, too,

Lyons' distinction between migration

and removal is on point: the

story-telling essay is a migratory form. "Stories," as Kimberly Blaeser reminds

us, "keep us migrating home" (qtd in Lyons, 5). Their discursive counterpart,

the argument grounded in "deliberate philosophy" with its quest for logical

purity, is necessarily a function of removal—more akin to assay than

essay. For

our present purposes, it is useful to know that the word "essay," used as a

verb, was once synonymous with the word "assay." Both imply a "trial" or "test"

(Hartle 4, 63). To essay, according to the OED, is to "put to the

proof." The emphasis, as I understand Hartle and Vizenor, is less on "proof"

than on "put": for the obligation of the essayist is to

chance the topic under review. In

what would seem a slightly different register, one tests for the presence of a

mineral by assaying, or proofing, its

ore. But are these truly different registers? Inasmuch as there is no gold standard for the logic of an

essay, how, for example, does one test for presence in an essay? As poet Diane

Glancy reminds us in a short segment on Vizenor entitled an "Essay on the

Essay," the "variable units" of Vizenorian language are "the four directions of

trick, disturb, interpret and realign." Glancy figures these verbs, each

stressing a dislocution or a dislocation, as cardinal virtues in Vizenor

country, even as they map out the contours of Glancy country as well. Within,

she goes on to explain, are "texture," and "a geology or geography of written

language as conduit" ("The Naked Spot" 279). The transmotion of Glancy's

figurations, from "texture" to "geology" to "language," invites a pivot from

the creative storytelling of essays

to the creation stories imbedded within geologic assays. In this case, the assays I have in mind are the core

samples by which petrologists test for oil. While the geologic story they tell

originates thousands of feet below ground and millions of years ago—from

time immemorial, we might say—the surface story plots out a narrative of

transmotion wherein the tragedy of removal might potentially allow MHA an

opportunity to frack out a migratory and redemptive irony of the last laugh.

After all, as we shall discuss, they, too, according to their creation stories,

came up to the surface from deep underground. II.

Reading from the ground up The idea of geology as a

story seems a foundational metaphor for North Dakota's Geological Survey

Department. In their 1997 guide book to the geology of the area around

Dickinson, North Dakota, Robert F. Biek and Edward C. Murphy explain that

"geologists often view the earth as a book." They go on to add that "the story

is not told in words and sentences... but in layers of rocks that record geologic

history. Each layer is like "a page in a book," with pages "grouped into

chapters and the chapters into four great volumes" (2). These "volumes," from

the earliest to the most recent, are the Precambrian or Cryptozoic, Paleozoic,

Mesozoic, and Cenozoic Eras (3). While Biek and Murphy go on to stress the

incompleteness of the text of geology, figuring that it might better be thought

of as an "incomplete diary," they nevertheless insist that the "record... with

careful observation can be pieced back together" (2-3). In The Face of North Dakota (2000), State Geologist John P. Bluemle

sounds a more cautionary note while utilizing a similar bibliographic analogy:

"The rocks and sediments found in North Dakota are not all the same age," he

writes. "Like the pages in a long and difficult history book, they record

events of the past. The 'book' however, is incomplete. Many pages are missing; other

pages—even entire chapters—are torn and tattered, difficult or

impossible to decipher." Missing pages notwithstanding, Bluemle assures his

readers that geologists "know" that "the record of life in North Dakota goes

back between 500 and 600 million years" (135). Much

of that knowledge is gleaned from core samples drilled in order to assay for

petroleum (Biek 3). And, in keeping with the bibliographic metaphor, these core

samples are readily available for review at the Wilson M. Laird Core and Sample

Library. With 18,000 square feet of climate-controlled storage space, this

voluminous facility "currently houses approximately 70 miles of cores and

34,000 boxes of drill cuttings," including about 95% of "the samples collected"

from "the North Dakota portion of the Williston Basin" ("Core Library"). Cores from the Bakken formation

constitute a significant portion of this archive, and to a State geologist they

provide the necessary texture with which to plot out their ur-text—a

creation story of the deep structure of North Dakota geology that intersects at

surface level with a complicated social history wherein land, water, and people

converge. The plot has its rising action in volume 2 (the Paleozoic Era), with

a series of transgressions and regressions of warm inland seas, and of the

consequent deposition and sedimentation of layers upon layers of mud mixed in with

the organic residue of lush, tropical vegetation.[7]

"Long after the sea... dried up," or so the storytellers say, "the weight of

thousands of feet of overlying rocks, coupled with heat from the earth's

interior" triggered in that organic slush chemical transformations that

produced petroleum. Additional pressure "caused the petroleum to migrate from

the source rocks (mainly shale) into more porous rocks (mainly sandstone and

carbonates)" [Bluemle 147-8]. As of now, the richest deposits in the Williston

Basin are to be found in the Bakken Formation, so named in 1953 by geologist J.

W. Nordquist after H.O. Bakken, the man who owned the land in Williams County,

North Dakota, on which the Amerada Petroleum Corporation took core samples from

its test hole #1.[8] A relatively

thin layer of source rock—only 46m thick at its "depocenter" (defined as

the site of maximum deposition)—the Bakken is a layer of "organic-rich

shales" that "overlies the Upper Devonian Three Forks Formation and underlies

the Lower Mississippian Lodgepole Formation" ("Diagenesis" 4). This would date

the formation at about 360 million years.

A

comparative analysis of core samples done by a well-trained eye can pinpoint

where the oil is and approximately how much of it has been generated. Indeed,

this is how the late Julie LeFever, geologist and longtime Director of the

Laird Core Library, earned her affectionate sobriquet of "Miss Bakken." She "knew where the oil was," according

to colleague Kent Holland. "She looked at nearly every Bakken core, logged it,

and put that information together.

She knew it was there before the technology existed to extract it"

(Orvik). According to a study published in 2001, by Janet

K. Pitman, Leigh C. Price, and LeFever, the Bakken "generated approximately 200

to 400 billion barrels of oil in place" ("Diagenesis" 1). As the 200 billion

barrel swing might indicate, oil generation estimates are in dispute. As

geologists develop ever more sophisticated computer models, the amount is

adjusted—sometimes higher, and sometimes lower. Even if all could agree

on a fixed amount, generated oil does not necessarily equal "recoverable" oil.

There is a great, and one supposes often frustrating, disparity between what

nature is deemed to have generated and what technology and pricing will allow

to be recovered. In a 2006 paper co-authored by LeFever and Lynn Helms,

legendary geologist Leigh Price is quoted as placing the recovery estimate "as

high as 50%." Headington Oil Company, operating in Richland County, Montana,

put a "primary recovery factor of 18%" for their operations, while North

Dakota's Industrial Commission came in with the most conservative estimate of

from 3-10%. Admitting that the "Bakken play" in North Dakota is still in a

"learning curve," LeFever and Helms go on to point out that technological

adjustments (including horizontal fracking) and the price of oil "will dictate

what is potentially recoverable from this formation" ("Bakken Formation"). In

2008, the State of North Dakota estimated that 11-14 billion barrels were

recoverable, whereas in 2013 the US Geological Survey put the number at just

under 7.4 billion (Gaswirth, et.al.).

Be

that as it may, they don't call it a "boom" for nothing. Actual production in

the Bakken, even with the recent plunge in oil prices, is still above a million

barrels a day.[9] And for

various reasons, not all of them good, that boom may very well reverberate in

MHA Nation for a long time. The Reservation is located right at ground zero of

what North Dakotans affectionately refer to as "the Patch." For MHA, the

metonym "the Patch" is counterpoised to an earlier metonym, "The Flood," the

traumatic effects of which have been intergenerational. It remains to be seen

as to what is ultimately "recoverable" within that scenario. Maps

of the Bakken Total Petroleum System (which also include the Three Forks

formation that undergirds the Bakken) show that the area under review stretches

east-west from longitude 99° in east-central North Dakota to longitude 107° in

eastern Montana, and north-south from the Canadian border (although the actual

geological formation extends into Manitoba and Saskatchewan) to latitude 45° in South Dakota. Compare those boundaries to the

following: Commencing

at the mouth of the Heart River; thence up the Missouri to the mouth of the

Yellowstone River; thence up the Yellowstone to the mouth of the Powder River,

thence in a southeasterly direction to the headwaters of the Little Missouri

River, thence along the Black Hills to the headwaters of the Heart River;

thence down the Heart River to the place of the beginning. ("Laws and

Treaties") So reads the language of

the 1851 Treaty of Fort Laramie. Starting at the mouth of the Heart, the

boundary circles back, as if to come home. These days, the southern boundary of "home" for the MHA

Nation is some 100 miles north, as the crow flies, from present-day Mandan, a

city situated at the mouth of the Heart on the west side of the Missouri across

from Bismarck, the state capital. A two and a half hour drive will get you to

tribal headquarters at Four Bears, across the river from New Town. At

approximately 500,000 acres, the tribal land base is miniscule compared to the

roughly 12 million acres allotted in the original treaty ("Demographics").[10] In

the oral tradition, this lost area is referred to as "the heart of the world." It was here, at the Heart River

villages, that the Mandan expanded their agriculture-based economy by

establishing a "great trading bazaar" that became a "commercial hub" along the

Mississippi-Missouri trade routes (VanDevelder 17). When Spotted Bear recounted

this history to me, he used the analogy of Sam's Club—a one-stop

retail-warehouse shopping experience under the corporate aegis of Walmart—to

connect MHA's past prowess as traders to today's commercial circumstances.

Archaeology bears this out. According to Elizabeth Fenn, at one particular

Mandan site in Hull, North Dakota (south of Heart River), "investigators have

unearthed items traceable" to locations as far-flung as the Pacific Northwest,

Florida, the Tennessee River, the Gulf Coast, and the Atlantic Seaboard (18).

Given the centrality of trade to agriculture-based and hunting-gathering

peoples alike, it would indeed be fair to call the Heart River villages "the

heart of the world." But the people of MHA had other reasons for calling this

the "heart" of their world. In one version of their creation story, Lone Man

and First Creator engage in a friendly contest to create their respective

portions of the world. They begin and end at the confluence of the Heart and

the Missouri (Fenn 5-6). As

it turns out, each of the Three Affiliated Tribes has some version of a

creation story that indicates an origin from deep underground. One Mandan account,

for example, as told to Wolf Chief by Chief, his Mandan father-in-law, tells of

"a high point on the ocean shore that the Mandan came from. They were said to

have come from under the ground at that place and brought corn up" (Bowers 2004

156). Wolf Chief was Hidatsa, and they, too, had tales that reckoned an

underground origin. In one account, from an unnamed source, it is said that

First Creator "caused the people who were living below to come above, bringing

with them their garden produce" (Bowers 1965 298). In Arikara origin stories

the people are likewise said to have come up from the ground, or from an

underground cave. As Star tells us, "A long time ago, people lived in the

ground" (Dorsey 18).[11] In

the time "long ago" it was corn and other garden produce that the people

brought with them from below. Since 2008, what comes from below has primarily

been a volatile mix of oil, natural gas, and wastewater. The nearly constant

movement of tanker and supply trucks is literally spreading and widening BIA

roads, most of which are unpaved. This constant rumble of oil-related products

is further complicated for MHA members by issues pertaining to resource

allocation, Native sovereignty, environmental concerns, and federal, state, and

local laws. Since the advent of

Bakken oil, MHA highway fatalities—"40 in the last few years," according

to Fox—have increased at an alarming rate[12];

drug and sex trafficking are rampant; and with the Four Bears Casino and the

expected revenues from oil, fewer and fewer youth are seeing any good reason to

further their education beyond high school. I learn all this from several

persons I was granted permission by Tribal administrators to interview during

the boom year of 2013. All of them

had at least a college degree, several had Masters, and one, Fox, a law

degree. Three of them had served

in a branch of the armed services. All are very alive to the deep irony of

recent tribal history in which MHA's best land had been "taken" in the late

1940s by the Federal government on behalf of the Pick-Sloan plan to dam up the

Missouri for purposes of flood control. The notion of "transgenerational

trauma" in reference to that post-Flood generation is a touchstone concept

expressed by almost all the people I interviewed.[13]

The youngest of these, Cory Spotted Bear and Lisa DeVille, live on the west

side of Lake Sakakawea, in Twin Buttes and Mandaree, respectively. MHA Nation,

and Mandaree in particular, turns out to be at the heart of the most productive

portion of the Bakken boom. Their stories show the extent to which creation is

an ongoing process. III.

Cory Spotted Bear "I'm to the top of my

head in the earth here," Cory Spotted Bear declares. We are sitting around the

dining room table of his house in Twin Buttes, North Dakota, on an early

afternoon in July, and he is explaining to me why he has no desire to move

away. Because he has just graced me with an hour-long survey of the history of

the MHA people, I think I know that this statement means more than a deep

personal commitment to the priority of place. As we have seen, since time

immemorial "the people" of MHA have always imagined themselves as having come

up from the ground. Spotted Bear, too, sees himself as emblematic of that

tradition. And at 36, he feels that he is just now beginning to emerge from the

ground up to grow into a vision of himself that he has been cultivating since

his senior year in high school. Signs

of a continuous past are all around us. There was the sweetgrass burned in the

smudge pot to welcome me into his home and to sanctify the time and space of

our conversation. There is talk of building an earth lodge on the grounds of

the local elementary school, just across the street from Spotted Bear's home.

Later in our conversation he will tell me that he is preparing for a sun dance

and will need to get a proper tree for the ceremony. Spotted Bear is a mesmerizing speaker, so I am not surprised

to learn that he is often called on by outside groups to talk about MHA-related

issues. For that reason, our time today will be limited, although he will give

me even more of it than I had hoped. A humble man, he seems almost embarrassed

to explain that shortly after I leave he will be relating his Tribal history to

a documentary film crew from Wales, chasing down the hoary old myth of the

"Welsh" Mandan. Spotted

Bear is proud to say that he grew up a reservation boy, raised in the old ways

by his grandmother, Olive ("Ollie") Benson. Mrs. Benson happened to be a

"full-blooded Norwegian," or masi,

but Spotted Bear tells me that because she was raised on the reservation and

because she had learned the old ways from her husband, Lorenzo "Larry" Spotted

Bear, he thinks of her unapologetically as a conduit for the old ways. One of

these teachings is to honor one's relatives. In light of that, Spotted Bear considers

himself to be "socially Mandan," while acknowledging his Norwegian and German

ancestry. "You must acknowledge your parts in order to be whole," he tells me.

But make no mistake, Spotted Bear affirms the synergy that the parts add up to

when he tells me, with pride quite evident in his voice, that, since both his

mother and father were half, he considers himself to be "full-blooded

Indian." Trying

to make tradition continuously present also means coming into contact with the

vestiges of genocide. There is the "historical trauma" that Spotted Bear identifies

with assimilation and acculturation when talking about his father and mother

and why they were ill-equipped to raise him. "After boarding school," he says,

"they say we did not know how to love our children." He was raised during

formative years by his Uncle and Aunt, Dennis and Berta, who taught him a good

work ethic by way of the many chores that a working ranch requires. Chores and good grades were a negotiating

point for the avid young basketball player. As

with many Native men, Spotted Bear sees in basketball an opportunity for young

persons to be "warriors." During his senior season in high school, he had what

he refers to as an "embarrassing experience with weed," one that left him

feeling psychologically unsettled for a couple of months. "I felt like

something was missing," he says, "I always felt like I was forgetting

something, or like there's something that should be there that wasn't

there." Spotted Bear says he

didn't really have a language for making sense of those uneasy sensations until

years later after he had begun sun-dancing. As he began to come to terms with

what he calls "the ceremonial way of life," he learned that "when we are not

doing good, part of our good spirit leaves us. It can't be around us anymore

because it is so pure, like a child." As he tells it, he now understands what

his spirit was doing during those two months. "It was up in the heavens,

talking to other spirits, talking to my ancestors, talking to my grandmas and

grandpas. And it was getting wisdom, and it was getting stronger, and it was

preparing to come back and start helping me down in this earth again." Grounded

once more, the consequences were very real for Spotted Bear. He began to think

about deepening his education in various ways. The BA he earned at Haskell and

the MA in Indigenous Studies from the University of Kansas may have provided

him with a credentialed portfolio that pointed him to the future, but his

experiences at these institutions also buttressed an intensifying commitment to

learning the old ways from his Elders, what he refers to as "teachings."

Without them, he would continue to feel as empty and rootless as he had after

that episode in high school. In asking about the old ways, Spotted Bear was

struck by how often his Elders would affirm the value of getting an education.

Both his Grandma Ollie and his Grandma Martina spoke of its importance, the

latter doing so on her deathbed. His late aunt, Alyce Spotted Bear, herself an

internationally recognized educator, had, during her stint as Tribal Chair,

guided MHA through the Joint Tribal Advisory Committee (JTAC) investigations

that eventually led, in 1992, to the allocation of an additional 149.2 million

dollar compensation for the tribal lands appropriated by the Forth Berthold

Taking Act.[14]

Raymond Cross had successfully argued that case all the way to the Supreme

Court. For Spotted Bear, a more complete education would have to embody not

only the academic finesse exemplified by Elders such as Alyce and Raymond, but

it would also have to include learning the intricacies of tribal ways that had

been passed down since "time immemorial." After

a detailed, and at times emotional, explanation of tribal and personal history,

Spotted Bear says, "Maybe you want to know my take on the oil." Based on my

introductory phone call, he knows that interviewing him on this topic is the

primary reason for my visit. But being a consummate host, he gently explains

the deferral in relation to the old ways. "The intelligent answer is the

pondered answer; I'm pondering things still," he says. "I'm okay with this oil

if we can do it in compliance. But because we went through so much trauma, we

tend to do things out of order. I could run an oil-field service, but are we going

to build a house on the ground or are we going to build a nice foundation

first?" After a short pause, he continues. "Let me paint a picture for

you: there are those of us who

absolutely love our way of life—the Earth way, the fact that we are

businessmen." It is in this context that he talks about Sam's Club and the

Mandan reputation as traders extraordinaire. Rightly proud of this tradition, Spotted

Bear thinks the oil can be leveraged in such a way that MHA can continue to be

trade brokers long after the oil is gone. "Today," he says, "what my view is

right now is that we can do these things in balance." Lest I get the wrong

idea about his self-interestedness, he quickly explains that he doesn't get any

oil revenue. "There is talk of a People's Fund," he says, "and I might possibly

get a monthly stipend off the interest from the fund.

Fig. 4 Are these trucks bringing water in or taking wastewater out? At

his invitation, we hop into his pickup for a tour of the area. He takes me up

on the buttes where many of the pump units, gas flares, and container pits are

located. We see trucks lined up at one site (figure 4 above). Are they bringing

the much-needed water for the fracking proppant, or are they waiting to carry

out the wastewater? It's hard to tell. But Spotted Bear frequently patrols the

backroads, doing what he calls "community watch" on what is, after all, his community. He occasionally queries

truckers pulled over to the side of a dead-end road or some out of the way

spot, and guesses they are probably illegally dumping drilling wastewater,

which, by some accounts, is "ten times saltier than ocean water" (Stockdill).

Fig. 5 This landscape scene could be the "before" to the scene with the pump, right.

"We left such a small scar on the

earth," he says wistfully, thinking back to his ancestors. "We lived in close

proximity to nature" (see figure 5, above). Then, as if to emphasize the

potential for oil to disrupt that equilibrium, he goes on to say that if "you

create a culture that you can be proud to claim, then in the process you are

reclaiming your past." To that end, he and others have started The Earth Lodge

Movement, dedicated to living in earth homes as sustainably and as

self-sufficiently as possible. "We are going to have a wind turbine," he says,

"even if we have to buy one from Menards." Spotted Bear's dream is that as

"inherent stewards of the land," MHA will be at the forefront of green energy.

It's in his cultural DNA, we might say. "I really believe I'm a plant, and that

I can walk around. This oil," he

continues, with a sweep of his arm, "this oil is going to make the wind blow

harder." I take him to be making a double-edged statement: that oil will make going green more

economically feasible, since the financial resources from oil revenue could

enable development of sustainable alternatives; and that if they wait until

after the oil dries up, going green will become more environmentally necessary

but by then it may be too late.

Since

my interview, Spotted Bear has been elected to MHA's Tribal Business Council,

where he currently serves the Twin Buttes segment (MHA is divided into six

administrative segments—the other five are New Town/Little Shell;

Parshall/Lucky Mound; White Shield; Mandaree; and Four Bears). The fact that

his subcommittee assignments are on the Education and Economic Development

committees bodes well, I think, for both Twin Buttes and for MHA. IV.

Lisa DeVille I first met DeVille in

the cafeteria at Fort Berthold College, in New Town, on July 10, 2013. She

immediately handed me an inch-thick dossier of documents related to various

issues, most of them oil-related, including some of her own environmental

impact studies. As I thanked her for the dossier, I couldn't help but think of

the Lac-Mégantic, Quebec, disaster four days earlier in which a train

containing Bakken oil had derailed and exploded, killing 47. The oil, so pure

as to be highly volatile, had been loaded in New Town. According to an article

in the Globe and Mail, local

residents in New Town "like to boast that the honey-coloured oil is so light they can

take it right from the well and pour it into truck engines because it requires

little refining" (McNish and Robertson). A point of local pride had just

erupted into an international nightmare, and as I would come to find out, those

are precisely the kinds of disasters that Lisa is concerned to prevent at the

local level. By the time I met her, DeVille had already

garnered quite a bit of attention as a go-to source for many journalists

working on MHA-related stories about "the Patch." Part of her appeal, I

suspected, is that she is very outspoken, absolutely unabashed about telling it

like it is from the perspectives that matter most to her: as a 37-year old

mother of five; as an enrolled member of MHA (Manda/Hidatsa); as a member of

Mandaree Segment much concerned with issues of equity and sustainability in

relation to the distribution of oil revenue that MHA holds in common; and as a

citizen who is very critical of the lack of oversight on the part of Federal,

State, and Tribal leaders in regard to environmental impact. As with Spotted

Bear, she, too, wants to push ahead into an oil-based future with an eye toward

promoting traditional values. Raised

in straitened economic circumstances, DeVille knows too well what it is to do

without. "I grew up hard," she informs me. "I didn't have a father. It was my grandmother who raised me. We

had alcoholism, my husband had alcoholism in his family. So we grew up hard. No

money. Sometimes we only ate once a day."

That personal past is what drives DeVille to focus her activism around

the holistic mantra of "healthy hearts, healthy minds, and healthy homes."

Given the amount of oil revenue coming into Tribal coffers, she is adamant that

there are "many, many, opportunities that Mandaree should be having right now.

Our children shouldn't be sitting there 90% obese. They shouldn't be sitting

there diabetic at the age of twelve or whatever. There should be a rec center,

and they should be incorporating more culture into our community." By "they," DeVille

means Tribal administrators, who, she feels, have thus far let them down.

Fig. 6 Emergency services are sorely needed in Mandaree. Fig. 1 Residue from flares turns some snow in Mandaree yellow.

Fig. 1 Residue from flares turns some snow in Mandaree yellow.

The

1940s Taking had such a traumatic effect on the Tribe as a whole that

reparation in whatever form is bound to be attractive, especially if it comes

with a healthy serving of poetic justice that made the bad land they'd been

shunted off to turn out to be the most valuable, at least in the short run. DeVille

is quick to point out that her husband, Walter, receives oil money from some of

his land but that, like Spotted Bear, she does not. All of this oil bonanza is

happening so quickly, and so inequitably, that she worries that MHA, in some

ways, is not ready for it. For this reason, they have to be prudent, she

thinks, about how they proceed. "We're modern today," DeVille explains, "but it

doesn't mean we have to give up our traditions." To punctuate her point, she tells

me that she knew what she wanted to be as far back as 7th grade. "It

was either going to be nursing, attorney, or business, one of the three. I

wasn't sure yet." She attributes her success in education to the fact that she

had people who believed in her. Her grandmother, who had just recently passed

away, made the biggest impact on her education. One day while they were picking

juneberries, she told her granddaughter, "People say there's oil under here,

but they can't get to it because of the boulders. They'll figure out a way to

get it, but I won't get to see it." "But she did get to see it," DeVille says.

"Then she told me, make sure you get your education, because you know the white

man, what they did to us before. When that oil gets here they're going to be

taking again. You get your education so when they put that paper in front of

you, you know what they're giving you." Or taking away, as the case may be. But DeVille is also quick to point out

that without sufficient oversight, Tribal authorities themselves may be

involved in underhanded or misguided deals that ultimately benefit themselves

at the expense of the Tribe.[15] Listening

to DeVille and her friend exchange opinions on this, I hear myself chiming in

with "The taking continues, but now it's an inside game," to which they readily

assent. One manifestation of this, as DeVille describes, is tribal leaders using

"tradition" as a way to bolster their own status. DeVille's own commitment to

tradition is very much in evidence in the way she talks about her own

upbringing and about how she is raising her own children. Her eldest son was

with her on the day we talked, and DeVille, who is Catholic, spoke proudly of

his having been selected to be a Tribal spiritual leader. "If you don't know

who you are," she says, "you're lost."

Since

our initial talk, DeVille's tireless efforts on behalf of keeping various constituencies—Tribal,

State, and Federal—attuned to the need for environmental awareness and

oversight have been recognized by the North Dakota Human Rights Coalition

(NDRHC). On Nov. 13, 2015, she received the Arc of Justice Award from the

Coalition. Barry Nelson, outgoing

chair of the Coalition, expressed the following sentiments in reference to her activism:

"Lisa DeVille embodies the NDRHC Arc of Justice Award in her lifelong quest for

justice and for advocating for the protection of the land about her. She is

someone that people can look to for inspiration and leadership." Nelson went on

to explain that DeVille was nominated due to her "strong record of achievement

combining skills in diverse areas of organizational development, group/staff

leadership, program development, project management, building partnerships and

community relationships." It is clear from the award and from her increasingly

diverse portfolio of committee and interest-group activities, including

membership on the Dakota Resource Council and the National Environmental

Justice Advisory Council, that DeVille is well on her way to becoming a State

and National figure on issues of environmental justice. But increased

visibility, while serving as a useful magnifier by which to augment her

critical opinion, is not her primary concern. Global exposure is merely a

function of local commitment. DeVille's primary concern is that MHA keep its

share of the exceptionally pure and extremely volatile oil safely on track for equitable and sustainable use for all members of MHA, now and in the future.

I

can easily envision a future in which Spotted Bear and DeVille both continue to

develop into exceptionally savvy and effective leaders. Spotted Bear's way of

surveilling his Twin Buttes community is to drive around and be a visible sign

of Native sovereignty; DeVille's way is to keep an ear to her scanner.

"Something happens almost every night," she says, "either a spill, something

tipped over, or something's exploded."

V: The

Fold in the Constitution

Raymond

Cross has consistently argued that if MHA is to benefit from the extraction of

oil rather than be victimized by it, then "reasonable legal and social

regulation" mandated by the Tribes will have to win out. If not, what looks

like a boon now may end up "jeopardiz[ing] the progress the tribal people have

made in their recovery from the disastrous effects of the Garrison Dam taking

some sixty years ago" (Cross 2011, 569). However, Cross thinks there is "reason

for optimism" since "both the federal and state governments have an important

stake in helping the tribe regulate oil and gas development." But in order to

turn Cross's optimism into hard fact, the other two governments will need to

"acknowledge the tribe as an indispensable

regulatory partner in the realization of this common goal" (569, emphasis

added). I take Cross's sly

invocation of "indispensable" as a way of gesturing toward the hard sovereignty

grounded in the commerce clause of Article I, section 8, clause 3 of the

Constitution, wherein is stated that "Congress shall have power to... regulate

Commerce with foreign Nations, and with the several States, and with the Indian

Tribes." Constructing the Tribes as "indispensable" partners is a way to undercut the authority of the halfway covenant

articulated by Chief Justice Marshall in Johnson

v. McIntosh (1823), in which the "doctrine of discovery" is presumed to

trump Native occupancy, and in Cherokee

Nation v Georgia (1831), wherein tribes are defined as "domestic dependent

nations."[16]

Rhetorically, if not legally, Cross's adjective "indispensable" turns

"dependent" into independent. Rhetorical

finesses notwithstanding, "the meaning of Indian tribal sovereignty within the framework

of U.S. Indian law" and its application across the legal landscape, as David

Carlson reminds us, remains "ambiguous." Carlson goes on to explain that "even

in the most generous interpretations tribal sovereignty has been held... to be

something inferior to state sovereignty" (30). This "something inferior"

originates with the Marshall Court's establishment of the "principle" that

"discovery gave title to the government by whose subjects, or by whose

authority, it was made, against all other

European governments, which title might be consummated by possession" (Johnson, emphasis added).

As

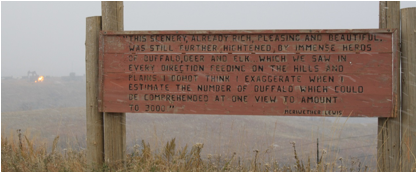

we were about to wrap up my October guided tour of Mandaree, we came upon a brown,

weather-beaten sign overlooking Lake Sakakawea, presumably set up by the BIA. Once

I read it, the situational irony between text and context was too tempting to

leave untended, so I got out and snapped a few pictures. The content of the

sign, as it turns out, is a quote attributed to Meriwether Lewis, one half of

the duo appointed by Thomas Jefferson to lead the Corps of Discovery.

This

scenery, already rich, pleasing and beautiful, was still further hightened by Immense

herds of buffalo, deer and elk... which we saw in every direction feeding on the

hills and plains. I do not think I exaggerate when I estimate the number of

which could be comprehended at one view to amount to 3000. (see figure 7 below)

Fig. 7 Excerpt from Lewis and Clark Journal

The

attribution is correct and is excerpted from a relatively lengthy journal entry

by Lewis dated Monday, September 17th, 1804. Given the placement of

the sign overlooking the Missouri near Mandaree, one might be excused for

thinking that Lewis was referring to what he encountered on that fall day in

what is now MHA country. As it turns out, though, the location that elicits

from Lewis such a gushing survey of aesthetic beauty "hightened" by a detailed reckoning

of material plenitude is actually located near the town of Oacama, in Lyman

County, South Dakota, closer to the present-day Crow Creek Sioux Reservation

than to the Heart of the World in Mandan country some 400 miles upstream (Journals 79-82). Placing the quoted passage back into the historical context

exposes some of the complications imbedded in the concept of sovereignty.

Reflecting

on the Lewis and Clark bicentennial "celebrations" that proliferated some 15

years ago along the expedition's route, Elizabeth Cook-Lynn, historian and

member of Crow Creek Sioux Nation, offers a survey of a different kind. "As one

surveys the history of massive land thefts, treaty violations, U.S. court

decisions, genocidal policies, and the diminishment of tribal sovereignty that

followed the Lewis and Clark adventure," she writes, "the hope of many Indians

that people of good and free will may rise up and make correct moral

determination is fragile indeed" ("The Lewis and Clark Story" 42). Such

fragility is further exacerbated by the aesthetic and environmental imperatives

invoked by the sign itself. Dislocated from its point of origin, the sign

unavoidably becomes a sign of absence, emblematic of all the dislocations so

recently enacted under the right of eminent domain. Vizenor, in comments

reflecting on Jefferson's attitude toward Native Americans, says that "Natives

were named in connection with the vast distances of an unexploited nation."

Viewed as a direct threat to the "vast," "unexploited" distances described so

agreeably in Lewis's account, "Natives," Vizenor concludes, "were removed as a

vindication of the environment. The absence

of the indian in the histories of

this nation is an aesthetic victimry" (Fugitive

Poses 21 emphasis in original). This sign, then, in its presumption of a

universalizing pose that dislocates geographic and cultural specificity on

behalf of celebrating, in the abstract, what

was once here, affirms, as well, the ways in which aesthetic contemplation

itself is an avatar of discovery. Franklin K. Lane, the Secretary of the

Interior when the first National Parks Portfolio was published in 1916,

imagined such contemplative engagement with iconic American landscapes as a

"further discovery of America" ("Introduction"). Add to this the unavoidable

fact that one can no longer view this particular sign, at this particular place,

without making visual contact with the oil rig and pumps operating in the

background, and one can begin to appreciate the extent to which Native sovereignty

is indeed a vexed concept. Legal pragmatists like Cross would take solace,

however, in the fact that "sovereignty," as Carlson stresses, "is truly

meaningful in its use and not as a

mere formal category or abstract concept" (30). "Sovereignty is the guiding

story in our pursuit of self-determination," declares Lyons, "the general

strategy by which we aim to best recover our losses from the ravages of

colonization: our lands, our

languages, our cultures, our self-respect." As a guiding story, it is

necessarily a nested narrative, one that simultaneously invokes the promises of

home even as it threatens the possibility of homelessness. Best then to

imagine, as Lyons does, that the "pursuit of sovereignty is an attempt to

revive not our past, but our possibilities" (449). From that perspective, those

rigs and pumps are as much a sign of "possibilities" at work as they are a

prompt for environmental protectionism. If the sign proper underscores Native

absence, the rig and pumps that ostensibly "mar" the "beauty" of the landscape

affirm Native presence as much as they underscore global capital. Where work is

to be done on behalf of "environmental protectionism," that work will have to

be undertaken and enforced by the very people who have for so long been its

primary victims.

For

Cross, then, living the lessons of the Taking, here and now, means insisting

that sovereignty will have to be both protected by the Tribes themselves and

respected by State and Federal governments. According to Cross, it is

sovereignty itself that hangs in the balance of environmentally responsible oil

production. "[T]he biggest potential adverse effect," he writes, "would be to

erode the tribe's status as an economically viable, and culturally intact,

political entity. Therefore, development, if it is not regulated in a legally

and socially responsible manner, may threaten the tribe's cherished political

and legal rights as a federally recognized Indian tribe" (Cross 2011, 543). The

warrant for Cross's concerns in regard to the potential for erosion of

sovereignty, if not its evacuation altogether, can be found in an obligation

mandated by the 1886 treaty with the Federal government "to use its tribally

reserved lands... as the means of achieving economic self-sufficiency" (543). That

self-sufficiency, and the sovereignty that Cross insists it anchors, "will be

sorely tested by large-scale development on tribal lands, though, because

development brings with it novel regulatory challenges that will test the

tribal people's sovereignty in new ways" (544).

In

order to reinforce the Tribe's continuing socio-political ties to reservation

land, Cross references the tribe's creation stories that "tell of how Lone Man

and First Creator selected the Fort Berthold lands as the tribal people's

permanent homelands." He goes on to emphasize that by virtue of "the people's

continuing re-enactment of their cultural and religious practices, they strive

to renew their ties to these lands and to help secure the creator's continued

blessing for their good uses of those lands" (Cross 2011, 545). In anchoring

his call for tribal sovereignty in his people's traditional creation story,

Cross reaffirms his own status as a tribal member, an affirmation that in turn

acts as synecdoche for the Tribe's

adherence to the mandates of the 1886 treaty. From Cross's perspective, American

legal mandates and his own Tribal obligations constitute twin creation stories

that, if treated with mutual respect, may "enable" the two cultures to

"navigate in what has become a 'splintered and disassembled' modern world" (Cross

2004, 65). Following constitutional scholar Martin Becker, Cross views "the

privileged moment" of the founding of the United States of America as a signal

event when "[t]wo Americas—one Indian and one non-Indian—were

simultaneously created" (61). This creational

doubling up becomes, for Cross, an opportunity for a creative doubling wherein Native and non-Native Americans can

dialogically "re-negotiate" their "civil compact" with one another. The short term goal for Cross would be

very much in line with the notions he espouses on behalf of safeguarding MHA

sovereignty by virtue of having a greater say in regulating environmental

protections—it's about "mutual and reciprocal respect" (64).

Such

dialogue will have to "meet a high standard" of mutual receptivity in which the

"interlocutors must embody" what anthropologist Clifford Geertz describes as

"'new ways of thinking that are responsive to particularities, to

individualities, oddities, contrasts, and singularities,'" that are in turn

"responsive" to a "plurality of ways of belonging and being, and that yet can

draw from them—from it—a sense of connectedness that is neither

uniform nor comprehensive, primal nor changeless, but nonetheless real" (qtd in

Cross 2004 65). Such a radical doubling, Cross stresses, will not be found in

"dreary tomes written by constitutional law scholars or the drab scientific

texts written by Indian anthropologists or ethnographers"—will not be

found, as Vizenor might phrase it, in the texts of manifest manners. It will instead be through the

"respective 'creation myths' these people offer to justify the great individual

and collective sacrifices demanded by the founding of the shared America we

know and love today" (66). From that perspective, as Cross makes clear, it is the

recognition of Native creation stories, Native experiences and Native

sacrifices—in short, Americans' reckoning with Native

survivance—that will provide the grounds for this new foundation.

"Native

stories of survivance are the creases of transmotion and sovereignty," Vizenor

reminds us (Fugitive 15). A crease

implies a fold unfolded, a mind made up and then unmade, an opening that

refuses the very closure that created it. Such is the history of American

treaty making, and hence the necessity for strategies of survivance. But how often can one fold and unfold

along the doubled crease of the Constitution before wearing thin the fold that

binds us? Better to move forward

into the future—however accidentally—with a clear legal vision and

a trickster's soul, than to be doubled over in the pain of a traumatic past

that cannot be recovered.

And yet "recovery," as it pertains to a past immemorial and the oil beneath the ground, will continue to be a key word—for the costs associated with rising waters have been that high. One would love to imagine a future in which the people of MHA, if they are careful stewards of their treaty obligations and their natural resources, will be in the right place to make the profitable commercial exchange when the price for water rises, as it inevitably will. While the past clearly has levied its costs in the form of intergenerational trauma, MHA leadership will have to proceed into the near future with eyes wide open and ears to the ground in order to ensure that the next generation is not permanently scarred by the negative environmental and cultural effects so often associated with extraction (figure 8, below). There is, for instance, anecdotal evidence of an alarming increase in human and drug trafficking, both of which are

Fig. 8 Sign on BIA 12, just west of Mandaree.

To emphasize the path MHA must travel to

engage the future that is best for them, Fox uses the example of two nearby

tribes. His aspirational ideal is embodied by the casino-rich Shakopee Mdewakanton

Sioux, located just southwest of the Twin Cities. There, each enrolled member

receives over a million dollars a year (see Daily

Mail, 8-12-12). Based on the

money already coming in to MHA coffers and on projections of future revenue, Fox

says that MHA "should wake up and we should be Shakopee—or close to it." In

this ideal vision, "everybody's got a home, everybody can work if they want to,

have an education, [and their] health system's good." As an example of what not

to do, Fox points to the once oil rich Fort Peck Reservation, circa 2013. "If

we don't change the course of where we're at, we're going to end up being Fort

Peck," he admonishes. "Go to Fort Peck.

What do you see? Poverty is

worse, crime is worse. They didn't

make the right choices." As a case in point, in 2011, as Fort Peck geared up

for another run at extraction, residents of the nearby community of Poplar were

dealing with the recent past in the shape of a "plume of salty brine" that was already

contaminating the local drinking water (Groover). Poised between the promise of

Shakopee and the problems of Fort Peck, Fox emphasizes that "if the end result

of somebody coming in and extracting that oil" is that we have to "take the

revenue just to deal with the extraction of it, then we've made a poor choice.

If that is the end result, then we better just leave it in the ground like a

bank account."