Indigenous

New Media Arts:

Narrative Threads and Future Imaginaries

THEA PITMAN

This

article seeks both to communicate a sense of the vibrancy and diversity of Indigenous

new media artworks and projects, and to "frame" them within the context of the

particular transnational networks of friendship and support into which they are

born and in which they circulate. It is my contention that Indigenous new media

arts[1]

have particularly flourished across the parts of the "Anglo-world" (Belich)

that are the result of the early waves of British settler colonialism, most

notably in countries such as Canada, Australia, Aotearoa/New Zealand, and the

United States (including Hawai'i).[2]

There are a number of reasons why

Indigenous new media art initiatives have really been able to thrive across

this particular geopolitical framework. Firstly, there is the nature of settler

colonialism itself and the type of transnational dynamics it leaves us with. In

distinguishing between colonialist and settler colonialist frameworks, critics

have noted that while the former privileges a centre-periphery dynamic, settler

colonialism is "inherently transnational" and requires a "'networked' frame of

analysis" to capture the movements and exchanges between colonies (Lester, qtd

in Veracini 10). Nonetheless, although the phenomenon of setter colonialism has

the capacity to bypass the original metropole, it still depends on that

metropole for the provision shared cultural values and a lingua franca through which cultural sharing may take place. Thus,

from the outset, there is a network of settler communities with lots in common

and a shared language in which to explore similarities and differences.

Furthermore, while the original

circuitry of settler colonial "worlds" is based on the movement and exchanges

between settlers rather than the Indigenous peoples the settlers sought to

displace, assimilate or eliminate, the same overarching networks and linguas francas have also been

strategically appropriated by Indigenous peoples to provide the framework for

the growth of a pan-Indigenous movement that has blossomed over the last forty

years. While this global Indigenous movement stretches far beyond the

"Anglo-world," Ronald Niezen argues for a predominance of Indigenous voices

from the "Northern Hemisphere," particularly Canada and the United States, in

the first Indigenous-specific meetings organised at the United Nations that

provided the basis for the development of this movement (69-72).[3]

Secondly, there is the critical relationship

between the global Indigenous movement and new media technologies. The development

of the Indigenous movement has been considerably facilitated by the rapid spread

of networked digital communication technologies since the late 1980s. As Niezen

notes, "the clearest evidence of indigenous networking can be found on the

Internet," and, drawing a comparison with Benedict Anderson's influential

arguments about the importance of the relationship between printing

technologies and the rise of nationalisms, he argues that "the development of

information technology has similar implications for the rise of international

consciousness among those marginal to nation-states" (226, n.12).[4]

Furthermore, it is worth noting that these technologies were developed first in

the United States, almost all computer programming languages are based on

English, and the lingua franca of the early internet was, by default, English.

Thus those Indigenous communities resisting within the "British" (post)colonial

settler world,[5] and who were

minded to appropriate the structures and technologies of that world to advance

their own decolonial agendas, were ideally placed to take advantage of new

technologies such as the internet and to undertake the networking necessary to

support the development of a nascent global Indigenous movement.

Furthermore,

Maximilian Forte argues that while "it is important to

underscore the extent to which the symbols and discourses of indigenous groups

in one part of the world can and do impact the symbols and discourses of

indigenous groups in another part of the world, especially on the Internet,"

the circulation of "globalized indigeneity" is not multilateral, and "North

American Indian labels, motifs, and representations" have significant sway in "influenc[ing]

contemporary articulations" of indigeneity elsewhere in the world.[6]

Other research in the field focusing on the first decade of the internet's

existence would suggest that even if Forte were not overstating the influence

of North American Indigenous iconography at the point in time that he was

writing, other sources of Indigenous influence were quick to spring up in

places such as Australia.[7] Nonetheless

the predominance of Indigenous voices and visions from

across the "British," "Anglophone" (post)colonial settler world in the context

of networked digital media is still apparent.

And finally, although new media technologies are

essential to the development of the contemporary global Indigenous movement,

new media arts per se have not

flourished everywhere that there are self-identifying Indigenous communities

that use the internet to network with other Indigenous communities, either in

English, or increasingly in other linguas

francas of colonisation that have substantially increased their presence

online such as Spanish or Portuguese.[8] It is the

case that, while socio-political conditions in (post)colonial settler

nation-states such as Canada or Australia are far from ideal from an Indigenous

perspective, these are nonetheless "'successful' colonies" (78) in Niezen's

terms: they are large, politically stable, liberal democracies with strong

economies that are well able to support and sustain a healthy Indigenous arts

"scene" in a way that has not been possible in other contexts either within the

"Anglo-world" or in other (post)colonial settler contexts such as Latin America.

It is this contrast between different

contexts and how they may facilitate, or not, the creation and circulation of

Indigenous new media arts that underpins my curiosity to explore the artworks

and projects that are the focus of this article. My main research interests are

in Latin American cultural studies, and I am currently involved with a project

entitled AEI: Arte Eletrônica Indígena

[Indigenous Electronic Art] (www.aei.art.br), run by the NGO Thydêwá (www.thydewa.org). The project promotes the

co-creation of what they refer to as "electronic art"[9] between

(typically) non-Indigenous artists and interested Indigenous community members

in nine different communities in the North East of Brazil. In order to analyse

and evaluate the artistic processes and products of the project, I felt the

need to familiarise myself with the kind of new media/digital/electronic

artworks and projects that I was aware were already being produced by other

Indigenous artists in North America. As I began this research, the need to

recognise the fact that new media arts created by Indigenous artists in the

United States and Canada exist in an "(art) world" that is distinctively

structured by the legacy of British settler colonialism, and has strong links

to other "comparable" countries such as Australia and Aotearoa became apparent.

The vibrancy of Indigenous new media

arts across this particular geopolitical framework is evidenced by a wealth of

different artists' networks, residencies, group exhibitions and anthological

publications. While some of these are confined to just one locale or, for

better or worse, nation-state, others seek to span the full geopolitical range.

Whereas more place-based and financially demanding activities such as

residencies, workshops and exhibitions tend to be circumscribed by local,

regional or national frameworks, arguably it is Indigenous-led

artistic/academic networks of friendship and support that are most likely to

span the full range of settings. The special issue of the journal Public, entitled Indigenous Art: New Media and the Digital (eds Igloliorte et al.,

2016), provides maximum proof of the scope and rationale of these networks. In

the introduction, Canada-based Indigneous editors Heather Igloliorte, Julie

Nagam and Carla Taunton are clear about the transnational (post)colonial settler

colonial framework that the works and projects selected span, although less so

about its British origins and Anglophone underpinnings: Despite the repeated

use of the term "global" in reference to the "Indigenous media art" showcased,

they also repeatedly emphasise that "This publication gathers scholars,

curators, and artists from the Indigenous territories in Canada, the United

States of America, Australia and Aotearoa" (9), all "colonized countries" (13)

that "share similar histories of settler colonialism" (6).

With what is such a dynamic, creative

"thread" of activity spanning across continents and oceans, it is an invidious

task to select materials for specific comment. I have thus structured what

follows around various vectors that will give a sense of the diversity of the

field: I start with some of the earliest projects, followed by those that most

clearly project Indigenous cultural imaginaries into the future ("First

Encounters and Indigenous Futures"). I then go on to explore the very different

modalities of Indigenous new media arts as well as some of the common threads

that bind them together ("Multidimensionality: Voices and Visions"), before

closing with a consideration of the different audiences that this kind of art

engages ("Sharing Indigenous New Media Arts").

In terms of the relationship of my

approach to Indigenous-led academic publications such as the special issue of Public mentioned above, as well as the

Canada-specific anthology Transference,

Tradition, Technology: Native New Media Exploring Visual and Digital Culture

(eds Claxton et al., 2005), and the North America-specific Coded Territories: Tracing Indigenous Pathways in New Media Art

(eds Loft and Swanson, 2014), these works for me constitute primary materials

in themselves. As Indigenous-led publications they provide compelling evidence

not just of the artworks and projects themselves, but also of the transnational

networks of friendship and support that underpin their creation and

circulation, and of Indigenous understandings of the purpose and intended

audiences of Indigenous new media arts.

First Encounters and Indigenous Futures

The

beginnings of Indigenous new media arts are contemporaneous with the

development of new media itself. Indeed, Indigenous engagement with computing

and with code as communication technologies go back at least as far as the

early twentieth century—Native American languages were used as code to

send messages in both First and Second World Wars (Eglash 181). In the case of

the development of the internet, the United States-based Ojibway artist

Hymhenteqhous Mizhekay Odayin, more commonly known as Turtle Heart, started

creating art on computers from the early 1980s (Eglash 182), and his American Indian Computer Art Project

website started life on a Bulletin Board System before being hosted by the

Massachusetts Institute of Technology as a World Wide Web site in 1991 (Turtle

Heart), i.e. before the Internet took off as a widely-accessible public

platform in 1994. The American Indian

Computer Art Project is essentially Turtle Heart's personal artist's

website, and it showcases his artistic trajectory, including drawings,

paintings, sculpture and computer-generated visual art, the latter a strong

thread throughout his career. According to the AICAP website, it was one of the first thousand websites ever to be

created and has been archived in the Permanent Collections of the United States

Museum of Computer History at the Smithsonian Institute. The site switched to

personal ownership in 1998 (http://www.aicap.org) and is still live on the

internet twenty years later—this quarter-century trajectory is quite a

phenomenal achievement for any web-based project.

Fig 1. Hymhenteqhous

Mizhekay Odayin/Turtle Heart, first

capture of the American

Indian Computer Art Project

website on Internet Archive Wayback Machine (12 Dec 1998). Reproduced with kind permission of the artist, for

academic and educational use only. No commercial use of any AICAP materials is allowed, implied or

granted.

While

Turtle Heart's AICAP is an individual

artist's website, and came about as a result of his close links with US

academics in the field of computer science (personal email), other Indigenous

artists in Turtle Island/North America, particularly those much further north

in Canada, first came to new media via the networking and dissemination possibilities

offered by the internet for spatially dispersed Indigenous artists, together

with the support of art institutions such as the Banff Centre for Arts and

Creativity in Alberta. Starting in the mid-1990s there were a whole host of

initiatives to network Indigenous artists as well as encourage take-up of new

media technologies through face-to-face events and exhibitions, online gallery

spaces and chatrooms. See, for example, Drumbytes.Org (http://drumbytes.org,

1994–), Cyber Powwow (http://www.cyberpowwow.net, 1996–), and isi-pikîskwewin

ayapihkêsîsak / Speaking the Language of Spiders (http://spiderlanguage.net,

1996–).

These early initiatives have also

continued to develop over the last twenty-five years and have led to Indigenous

media arts research networks such as Aboriginal Territories in Cyberspace (AbTeC;

http://abtec.org, 2004–) and more recently the Initiative for Indigenous

Futures (IIF; http://abtec.org/iif; 2015–), both led by Cherokee/Hawaiian/Samoan academic

and artist Jason Edward Lewis and Mohawk/Irish artist Skawennati. As Lewis

notes, while AbTeC was focused on "claiming territory in the newly formed

virtual places of cyberspace," IIF directs its attention at "claiming territory

in the future imaginary, or better yet, creating our own" (Lewis 37). Both

initiatives thus ensure Indigenous presence in virtual and/or imaginative

spaces to contest the dominant view that these spaces are terra nullius where "white" people can make themselves at home

having removed any concern for competing and/or prior claims for such space, or

where their dominance will inevitably prevail after many battles (the typical

narrative arc of Western science fiction).[10]

Lewis's and Skawennati's own artistic

outputs are important in their own right. See, for example, Skawennati's

complex and painstaking TimeTraveller™

(http://www.timetravellertm.com, 2009–) video-art project created using

machinima technology that records real-time interactions in gaming

environments, in this case the actions of avatars created by the artist to

support roleplay scenarios in Second Life, and which retells significant

episodes of history from a First Nations perspective (Ore; LaPensée and Lewis).

Fig

2. Skawennati. "Dakotas Raise Weapons",

machinimagraph from TimeTraveller™

(2010). Reproduced with kind permission of the artist.

Image may not be reproduced without permission.

However, what is perhaps even more

important is the fact that the directors have arguably inspired a whole

generation of Indigenous artists to work with computer gaming technologies

through the Skins Workshops on Aboriginal Storytelling in Digital Media (http://skins.abtec.org)

that AbTeC has been running since 2008. (See, for example, the work of Beth

LaPensée.) These workshops have focused on developing the potential of

Indigenous youth from a wide variety of different ethnic groups, predominantly

in Canada but also in places such as Hawai'i, to simultaneously engage with new

technologies and with their own cultures through the design of computer games

that represent them and their worldviews, including their visions of what kind

of futures they want to have. This is not only important in terms of ensuring

the passing on of Indigenous knowledge and cosmovisions (worldviews), from

generation to generation, but also in terms of contributing to the envisioning

of possible futures for the whole of humanity. That is to say, one hopes that

Indigenous science-fiction imaginaries can offer much needed correctives to the

above-mentioned mainstream science-fiction narratives that tend to rerun

colonialist first-person-shooter scenarios, thus delivering only the

unimaginative futures conjured up by those who hanker after the glories of

conquests past.

Similar initiatives are also evident

elsewhere in the British settler colonial world, such as in the Pilbara region

of Australia, where Ngarluma youth have collaborated on a project

sponsored by Big hART—a not-for-profit community arts initiative—

to create an interactive animated science-fiction comic storybook for iPads

called The Neomads (http://yijalayala.bighart.org/neomad,

2010–), and which is based on "Dreamtime stories about the land, seas and

rivers, sacred sites and spirits" (Bessant and Watts 1). Bessant and Watts

voice some concerns about the ability of the project to not simply further

essentialise and commodify Indigenous identities in a new medium and to offer

real agency for the Ngarluma youth

involved (11-12). Nonetheless, they conclude that "The Neomads contests the idea of who is a 'real' Aboriginal by

demonstrating that the young participants are savvy technicians skilled in new

media" and "creative bricolage," and that they are able to use new media to

strengthen their sense of community belonging, as well as relate to a

fast-changing, multicultural world (Bessant and Watts 11-12). Thus, through

these gaming imaginaries, and the creative, intercultural skills and

positionalities developed in their composition, Indigenous youth and artists

can be seen to be making a significant contribution to future-proofing their

cultures.

Multidimensionality: Voices and Visions

The

different manifestations of Indigenous new media arts are as diverse as one can

imagine, ranging from Inuit (Pond Inlet, Nunavut) artist Ruben Anton Komangapik's

Nattiqmut Qajusiqujut (the seal that

keeps us going) (2014), a 15cm-wide mixed-media piece combining harp seal

skin, various different metals and nylon thread and incorporating a QR code

dyed into the seal skin which leads to a YouTube video of the artist telling a

family story of cultural survival; to British/Māori (Ngapuhi, Ngāti

Hine and Ngai Tu) artist Lisa Reihana's c.20m-wide and 4m-tall,[11]

64-minute-duration video installation In

Pursuit of Venus [Infected] (2015-17). The latter work took Reihana ten

years to create and it is based on a revisionist re-enactment of first

encounter between Indigenous people and Captain Cook and his crew in Tahiti for

the 1769 Transit of Venus—a prelude to the colonisation of the entire

region—as seen in "a scenic wallpaper from 1805 called Les Sauvages de la Mer Pacifique (or Savages of the Pacific), created by

French manufacturer Joseph Dufour based on the design of painter Jean-Gabriel Charvet"

(Jefferson). In the "digital wallpaper" installation, the figures depicted

"come to life," embodied by Australian Indigenous actors in the main, and act

out vignettes that trouble any Manichean readings of the narrative of first

encounter, encouraging viewers to adopt their own point of view (a play on the

work's acronym, "POV"). Yet, despite vast differences in materials or scale,

there are, nonetheless, obvious common threads running across a great many of

these works relating to questions of Indigenous voice and agency, cultural

heritage and "story-telling" via new media, as well as wider questions of

cosmovision and ethics of representation.

Fig

3. Ruben Anton Komangapik, Nattiqmut Qajusiqujut

(the seal that keeps us going) (2014). Harp seal skin, indelible

ink, steel, bronze, sterling silver, nylon cord, and waxed nylon, 114.5 x 180 x

6cm, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. Reproduced with kind permission of the

artist and the National Gallery of Canada. Image may

not be reproduced without permission. Scan QR code with any QR code reader to

access the video.

Fig

4. Lisa Reihana, In Pursuit

of Venus [Infected] (2015–17). Single channel video, 16k Ultra-HD video, colour,

sound, 64 mins, c.20m-wide/4m-tall screen. Supported by Creative New Zealand, New Zealand at Venice,

Artprojects, Campbelltown Arts Centre, Park Road Post. Installation view, Lisa

Reihana | Cinemania, Campbelltown Arts Centre, 2018.

Photo: Document

Photography. Reproduced with kind permission of the

artist and CAC. Video footage showing how the

installation was made and how it works available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WmMRF5nw9UI

As Jason Edward Lewis argues, the

multidimensionality of digital art forms (the facility to provide different

layers or divergent narrative threads via links, for example) is an excellent

way of providing "a much fuller picture of what this history is or what this

contemporary situation is" and ensuring that a wider range of voices can be

heard (Lewis, in interview with Smyth). Excellent examples of layering,

multi-voiced-ness and alternative means of story-telling are to be found in the

multimedia work of Diné (Navajo) artist William Ray Wilson. In a series of

beadwork "weavings," including Auto

Immune Response: Weaving the Sacred Mountains (2011-12) and eyeDazzler: Trans-customary Portal to

Another Dimension (2011), Wilson embeds scannable QR-codes into the

weavings. In Auto Immune Response these

QR-codes link to short videos that focus on "a post-apocalyptic Navajo man's

journey through an uninhabited landscape," and raise questions about ecological

change, the loss of key Indigenous sacred landscapes, and the possibility of

survival and "reconnection to the Earth" (Wilson, interviewed by Moomaw and

Lukovic). In eyeDazzler, a much

bigger public-art piece made of 76,000 4mm-diameter glass beads, the textile is

much more complex in itself, referencing a particular two-sided Navajo textile

design as made by the artist's grandmother. Where the

cultural knowledge required for the elaboration of such traditional textiles is

being lost, Wilson uses two identical QR-codes to offer an alternative

"trans-customary portal" (in his terms) to access that knowledge—the

codes lead to a two-channel video of his mother and aunt discussing, in Diné,[12]

how

their mother had made the original rug, while the viewer sees images of how the

new rug is being made and who is involved in the project.[13] As Wilson

notes, rather than simply foisting something new and high-tech onto an artform

perceived as "traditional" and "static," "our project was always about working

from within and developing a trans-customary form based on something that our

mothers and their mothers before them have always been innovating" (Wilson,

interviewed by Moomaw and Lukovic). The eyeDazzler

project was also a community collaboration, given the enormity of the task of

making the piece, and designed as a piece of public art to complete the

feedback loop between creative communal praxis and its intended local

(Diné-speaking) audience.

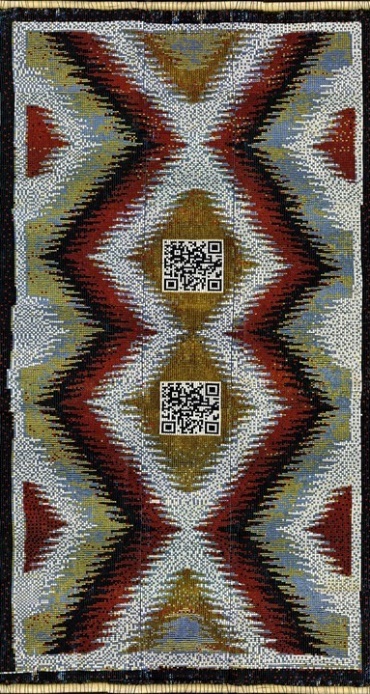

Figs

5 & 6. William Ray Wilson, eyeDazzler:

Trans-customary Portal to Another Dimension (2011);

whole work and detail. Reproduced with kind permission

of the artist.

A more recent project that evidences

the facilities of "layering" in digital art, is Wilson's Critical Indigenous Photography Exchange (CIPX) which includes a

series of eight "talking tintypes" (https://willwilson.photoshelter.com/gallery/Talking-Tintypes/G0000n_hiXQrBXNw,

2015).[14]

These are conventional-looking ethnographic black-and-white tintype photographs

of Indigenous subjects in the style of Edward S. Curtis. But these are not just

conventional ethnographic portraits, presenting objectified, decontextualised

images of unnamed Indigenous subjects for consumption by the Western gaze. The

"exchange" of the title suggests that these images are the result of a

collaborative "exchange" between sitter and photographer which grants the

sitter greater agency in the way in which they are represented and offers new

ways for viewers to understand contemporary Indigenous identities. It effects

this exchange by means of adding new layers to the ostensibly traditional

image. Indeed, when they are scanned with an Augmented Reality app (Layar), the

images are overlayed with video material from the sitting such that sitters can

both return the viewer's gaze and speak for themselves.[15]

The results, as readers may judge for themselves by downloading the free Layar

app and scanning the images below, are really very arresting and effective.

Figs 7 & 8. William Ray Wilson, "Insurgent Hopi

Maiden" (2015), and "Chairman

Shotton of the Otoe-Miossouria Tribe" (2016), from the "Talking Tintypes"

series in Wilson's Critical

Indigenous Photography Exchange (CIPX) project. Reproduced

with kind permission of the artist.

Another way of thinking about the issue

of layering in these images is also to consider the fact that Wilson has chosen

to include some ostensibly Latina/o subjects alongside

the Native American sitters,[16] thus

hinting at the complexity of the relationships and/or overlapping identities

between Native American communities in the South West, the large, and

fast-growing, numbers of mestiza/o

(mixed-race) Chicanas/os and Latinas/os in the region, and the

not-insignificant numbers of Indigenous community members from further south in

the Americas who have settled in the area. While the majority mestiza/o population likes to emphasise

its Indigenous ancestry as a way asserting an a priori right to reside in the

US Southwest and emphasising its own sense of colonisation by Anglo-America,[17]

this indigenist dynamic also tends to erase the presence of self-identifying

Indigenous peoples among the Chicana/o and Latina/o populations as a whole.

Indigenous people of Latin American origin in the US Southwest have to

negotiate their multiple oppressions as both Indigenous and Chicana/o or

Latina/o, as well as the complexity of their "settler" relationship vis-à-vis Native

American communities in the region. As critics have noted, these are "layered,

complex, multifocal, and multi-vocal Indigenous" (Blackwell, Boj Lopez and

Urrieta Jr, 132) identities that are very much part of the contemporary,

transnational, transcultural, and cosmopolitan forms of indigeneity (Forte)

that Wilson sought to photograph.

A significant amount of Indigenous new

media arts created to date has come in the form of large-scale digital video

and multimedia installations. Lisa Reihana's Tai Whetuki—House of Death Redux (2015), for example, focuses

on Māori and Pacific rituals around death and mourning. The two-channel

video installation takes up two whole sides of a room that is otherwise in

complete darkness. Nonetheless, the videos are designed to partly project, and

partly reflect onto the polished floor, thus over-spilling their "natural"

limits, and a hazer is also used to create a mist that is picked up by the

light of the projector. This last element was intended by Reihana to evoke a

sense of "spirit" (interview with Tamati-Quennell 67).

Another example—one that offers a

meta-narrative about "old" media and voice to boot—is The Phone Booth Project (http://www.lilyhibberd.com/The_Phone_Booth_Project_new.html,

2012-13), by non-Indigenous Australian artist Lily Hibberd and Martu filmmaker

Curtis Taylor. The installation stems from a community-based project around the

social role still played by phonebooths in the remote communities of

Australia's Western Desert (Biddle, Hibberd and Taylor 110). When installed in

the Furtherfield Gallery in Finsbury Park for the Networking the Unseen exhibition of Australian aboriginal digital

art curated by Gretta Louw in summer 2016, the installation consisted of three

whole-wall videos featuring Martu community members discussing, in different

languages (but with subtitles in English), what the phonebooths meant to them,

how they have appropriated this technology, as well as other footage of the

booths in the communities. In the same space there was also a real phonebooth,

red sand on the floor and lighting to mimic the pounding heat of the desert sun

(Rai).

In both these cases, what is important

is the immersive, visceral impact of the installations: this aspect is really

enhanced by the non-digital elements that force viewers to engage with the

works through all of their senses. This decentring of the digital, relegating

it to be just another means for communication that Indigenous artists may

appropriate at will, is a helpful corrective in a field that has often given in

to too much celebratory, utopianist hype about the potential of digital media

to revolutionise human society, including "freeing us from the meat" of our

carnal bodies and painstakingly-negotiated social identities.[18]

Furthermore, the "whole-body" experience offered by such video installations

helps to move them beyond the conventions of "Western" documentary practices,

and works, instead, to engage the viewer with Indigenous cultural repertoires.[19]

Fig

9. Lisa Reihana, Tai Whetuki—House of Death Redux (2015). Ultra-HD, widescreen cinema aspect

ratio, 2-channel video, sound, 14 mins. Photograph of the installation at The Walters Prize 2016 exhibition,

Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, 2016. Installation

view, Lisa Reihana | Cinemania, Campbelltown Arts Centre, 2018.

Photo: Jay Patel. Reproduced with kind permission of

artist and CAC. Sample of video available at:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x6tVOhG2Ruo

Figs 10

& 11. Lily Hibberd and Curtis Taylor, The

Phone Booth Project (2012-13). Photographs of

installation as featured on the project website. Website also includes sample

videos. Reproduced with kind permission of the artists.

Sharing Indigenous New Media Arts

Indigenous

new media artists and community art projects have flourished across the

contemporary British (post)colonial settler world over the last twenty years

(or so), particularly in Canada, the United States, Australia and Aotearoa.

Integral to this flourishing, such artists and projects have often used the

networks of friendship and support provided by other Indigenous artists and supporters

elsewhere in that "world," as evidenced by the Indigenous-led works of

scholarship on the subject, in order to strengthen their sense of identity as "Indigenous

peoples," as well as raise the profile of this kind of art. But the question

remains, raise the profile with whom? Who is the intended audience of this kind

of art?

As the

editors of the special issue of Public

dedicated to Indigenous Art: New Media

and the Digital (2016) note, their anthology was designed precisely "to

showcase the invaluable momentum created by existing global networks of

Indigenous artists, curators, and scholars, and to share the knowledges and

practices advanced through such networks" (Igloliorte et al., 6). Elsewhere in

their introduction, however, the editors make the case for the primacy of

global Indigenous artistic and cultural exchange achieved through these works

and projects, of an engagement with Indigenous (counter)publics, invoking the

potential that these practices have to promote decolonial forms of critical

mass referred to as "gathering" (they

appropriate Māori scholar Linda Tuhiwai Smith's term), "Indigenous networking," and "Indigenous-to-Indigenous

dialogue around the world" (Igloliorte et al., 6).

Nonetheless, in the earlier Indigenous-led,

Canada-specific anthology, Transference,

Tradition, Technology: Native New Media: Exploring Visual and Digital Culture

(2005), one of the editors, Dana Claxton, specifically notes that as Indigenous

new media arts become more recognised and enter formal gallery spaces, they are

predominantly appreciated by a "non-Aboriginal audience" (16). Despite voicing

concerns about the possible co-optation of Indigenous new media art by the

dominant, largely non-Indigenous academy and art world, Claxton is positive

about the decolonial potential of the increasing presence of Indigenous new

media art works in such fora, hoping that the exchange with the non-Indigenous

viewer can be "one of pedagogy, understanding, truth, hope" (16), building "trust

and interrelationships with non-Aboriginal and Aboriginal communities" (17).

She goes on to argue that "By decolonizing the exhibition space and art

discourses, an Aboriginal worldview will flourish, taking hold within the

artworld" (17).

It is in this sense, then, that we

should celebrate the fact that the most successful of Indigenous new media

artists featured in this article now figure in the exhibitions and permanent

collections of major institutions both within the geopolitical limits of the contemporary

British (post)colonial settler world, as well as beyond. For example, an

installation of Lisa Reihana's In Pursuit

of Venus [Infected], called The

Emissaries, was selected for exhibition

in the New Zealand pavilion at the 2017 Venice Biennale, and praised as the

best work of the whole exhibition by eminent art critic Waldemar Januszczak.

At present (November 2018), the same work is being exhibited at the Royal

Academy in London as part of the impressive "Oceania" exhibition of indigenous

art from the region, from first encounter to the present day. The presence in

these venues of Reihana's large-scale critical revisioning of first encounter

is a significant part of what a decolonisation of those spaces entails,

particularly given their tendency to function within the nation-state framework

of international "world fair"-like exhibitions or anthropologically-curated art

"spectacles" reminiscent of the imperial-legacy collections of "world" art in

places such as the British Museum.

Other of the artworks featured in this

article have recently been purchased by major galleries in the relevant

(post)colonial settler nation-states that clearly seek to expand their

collections to be more inclusive of the ethnic diversity of the nation in question.

See, for example, Ruben Komangapik's Nattiqmut Qajusiqujut which has been purchased by the National Gallery of Canada,

or some of Will Wilson's photographs that are now held by the Portland Art

Museum. While this is also to be celebrated, one of the dangers with purchase

by art galleries is, however, that they place a stranglehold on the further

circulation of (images of) such works such that they are reserved only for

those with the cultural and economic capital required to visit such institutions

or to purchase expensive art books.

A lot rides, therefore, on the careful

curation of international exhibitions and state-owned collections so that

Indigenous new media arts are not shoe-horned into "frame"-works that limit and

neutralise their ability to communicate, nor made inaccessible to those

communities whose stories they tell. Furthermore, circulation in such fora

should, of course, not be taken as the only measure of success. Travelling

exhibitions that take works to Indigenous communities themselves and

co-creative community new media arts projects have an important role to play in

ensuring that Indigenous communities continue to be both participants in the

creation of such works as well as the primary audiences thereof.