"#morelove.

always":

Reading Smokii

Sumac's Transmasculine First Nations Poetry on and beyond Social Media

JAMES

MACKAY

queer bright

ktunaxa and proud

two spirit is a

responsibility a

relationship with

all of creation

but most of all with myself

and i'm just learning

to be kind to be

unapologetic so

please let me breathe deep

into who i am

Smokii Sumac is

a member of the ?Akisq'nuk Band of the Ktunaxa Nation as well as a citizen of

Canada, a poet whose excitable generosity of spirit shows in the dedication of

his debut collection you are enough:

poems for the end of the world (2018) to more than 125 individually named

people (some of them likely non-human). In a review essay written for Transmotion in 2017, and therefore

coterminous with the creation of that book, Sumac describes himself as follows:

I am queer, nonbinary,

transmasculine, and a poet. I am a writer, a PhD Candidate, and an instructor

of Indigenous literatures and creative writing. I am cat-dad, an auntie, an

uncle, a sibling, and a child. I am hyper-aware that even as I write this, my

experience of gender is shifting, changing, and growing. ("Two Spirit and Queer

Indigenous Resurgence" 168)

This series of

identities is given in a way that both complicates and refines Sumac's original

description of himself as Two-Spirit, and goes a long way to explaining the

joyfully expansive sense of multiplying identities that resonates throughout you are enough—which also includes

reflections on being a recovering addict and self-harmer. Sumac is clear that

Two-Spiritedness in itself is not a noun of identity so much as it is a verb of

performing responsibility, and that this responsibility is specifically decolonial.

In so doing he shares in a long lineage of Two-Spirit writing that seeks, in

Qwo-Li Driskill's phrase, "a return to and/or continuance of the complex

realities of gender and sexuality that are ever-present in both the human and

more-than-human world" (55), and which have been disrupted by the colonial

project.

There

are also some distinctions that need to be made when thinking about Sumac's

writing in such a context. Much previous scholarship on Two-Spirit voices has

concentrated, rightly, on the ways that creators such as Chrystos, Beth Brandt,

Maurice Kenny and Paula Gunn Allen primarily work to overcome erasure. Such an

attitude can be detected in the defiant title of Chrystos's first collection, Not Vanishing (1988), or when Janice

Gould describes a feeling of "being disloyal and disobedient to the patriarchal

injunction that demands our silence and invisibility," for example, just for

"speaking about lesbian love" (32). Craig Womack's novel Drowning in Fire (2001), published only twenty years ago and one of

the first full-length novels with an LGBT Native American protagonist was marketed as "groundbreaking and

provocative."

And Lisa Tatonetti, in an overview of thirty years of the journal SAIL, observes that academic criticism's

explicit engagement with queer contexts did not emerge for the first twenty

years of the journal's existence: it is only with Qwo-Li Driskill's 2004 essay

"Stolen From Our Bodies: First Nations Two-Spirits/Queers and the Journey to a

Sovereign Erotic" that "conversations about sovereignty and sexuality entwine"

(Tatonetti 154).

However, a strong focus on erasure does not quite do justice to the

current situation. Sumac is not contemporaneous with the group described above,

but is rather a part of a new generation, inheritors of decades of activism.

While homophobia, transphobia and settler erasure of Indigenous identities very

much remain active forces in 21st century Canada, Sumac and his

peers are able to access far greater resources and longer traditions of LGBTQIA+

(and particularly Two-Spirit) writing. With the sole exception of Max Wolf

Valerio, discussed by Lisa Tatonetti elsewhere in this special issue, there are

almost no literary transmasculine Indigenous forebears for him to draw upon. Yet

there are far greater resources than would have been available even a decade

previously, including historical recovery work and contemporary trans*

Indigenous groups.[3] Gwendolywn

Benaway demonstrates this in her essay "Ahkii: A Woman is a Sovereign Land" not

only by being able to discuss trans* historical personages and provide archive

photographs of trans* people, but also by noting that one of the problems she

encounters is that her interlocuters "don't want to wear the label of racist or

transphobe" (114). In other words, while people with transphobic views continue

to have powerful platforms, it is transphobia that is now increasingly seen as

a cause of shame in mainstream culture. Sumac's short career as a writer also

includes working with an entirely Indigenous publisher, Kegedonce, which had

been promoting First Nations voices for twenty five years when it accepted his

manuscript. He has also won Indigenous Voices Awards in both the inaugural year

of that crowd-funded Indigenous-only prize and the following year. All of this

makes for a better and more public support system than any Indigenous trans*

writer of even a decade previously could have enjoyed.

In

this article I explore the effects and ramifications of one specific venue for

that community. Sumac's poetic

practice is, I would argue, intimately bound up with social media. In an

interview we conducted in February 2020, he confirmed that many of the poems

from the collection were first posted to his Facebook account under the hashtag

#haikuaday and that publication had not originally been a goal (Mackay, 120).

It was only after meeting people who had enjoyed the poems that he decided to

collect them, and his publisher also approached him after becoming aware of the

poems on social media. He was also clear that social media affected the form,

stating in interview that "At one point my editor said, 'I don't know

why you have a period in some places and why in some you don't.' And I said, 'Well,

because they were all written on Facebook!'" (120). As I explain below, even

the cover of the collection is inspired by social media, being modelled on an

Instagram feed. Clearly Sumac is comfortable within digital environments, and

finds them both nurturing and sustaining. One could even argue that the social

media environment has worked its way into the very language of the book: in

creating the word cloud I explore in the final section, I discovered that the

second most common word in the book, iterated 76 times across 98 pages of

poems, is "like."[4]

There are many further ways in which spaces such as Facebook, Instagram,

YouTube and Twitter are very far from being neutral areas for self-exploration.

Designed to maximise user interaction, the better to generate data to sell to

their customers, the platforms utilise complex machine algorithms to determine

the placement of content within the feed, literally determining how many other

people will see anything self-published on the platform. The result is the

creation of millions of mini-communities, each centred on one person, in which

the platform and the individual collaborate to filter out unpleasantness. The

environment itself is characterised by, among other things, the haptic

experience of users sliding their finger across a smartphone and receiving

feedback in the form of vibration and sound alerts, the stress on "clean"

design elements in each of the major platforms, and the fact that these

platforms are available 24/7, often as an escape from boredom or stressful

situations, all of which further serve to alienate the user from everyday life

in the service of multinational corporations' mission to monetise everyday

life.

In this article, then, I intend to explore the ways that Sumac creates a

Two-Spirit transmasculine role for the 21st century within such an

environment. I begin by looking at the cultural implications of Sumac's choice

of cover images, comparing these with the choices of his trans* poet peers, and

use this as the springboard to a discussion of Sumac's use of social media

tropes, particularly hashtags, that situate his poetry as the product of a

specifically digital environment. This, I argue, is simultaneously a welcoming

space for trans* and Indigenous people to find community and develop communal

identities unaffected by physical distance, and also a space that carries

particular dangers not only for both groups, but also for creative artists, in

its flattening of affect. Finally, I look at the poet's use of natural

environments and images, and the ways that these function to balance and

indigenize a shifting and uncertain digital no-space.

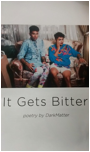

Cover Story

Recent years have seen a surge in the number of poetry

collections, chapbooks and anthologies of poetry by writers who identify as

trans*. While this genre cannot be said to have become widespread enough to be

predictable, a certain sameness does seem to have crept into the covers for

trans* authors' work. In making this statement I draw on two sources: the

GoodReads list titled "Poetry collections by trans / nonbinary / genderqueer

etc. non-cis authors" (Takács 2017), which as of June 2020 contained a sampling

of 139 such collections, and the finalists for the Lambda Literary Award for

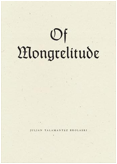

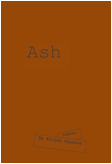

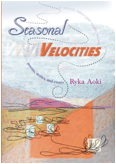

Best Transgender Poetry since 2015 ("Previous Winners"). Four major strands of cover design stand out. First,

as is common in 21st century

publishing, some collections, such as those from Julian Talamantez Brolaski,

Kari Edwards, Elijah Pearson and

Melissa Jennings, opt for simple typography as the

major visual element of their covers (Figure A). A particularly common trope

(which may also reflect general trends in poetry publishing, but seems

particularly motivated in the case of transgender authors) sees covers use abstract

or non-figurative art to suggest concepts of change (Figure B), with a

positively deleuzoguattarian visual language that emphasises rhizomatic lines

of flight (Ching-In Chen, Xandria Philips, Andrea Abi-Karam), holes (Jos

Charles, Yanyi), or maps and/as rhizomes (Ryka Aoki, Ashe Vernon & Trista

Mateer). Other covers depict the human figure, but use stylized art to situate

it as becoming or escaping, as in the examples from Gwen Benaway, Joy Ladin,

Kayleb Rae Candrilli and Max Wolf Valerio, as well as TC Tolbert and Trace

Peterson's edited collection (Figure C). This trend is developed in the last

major strain of cover art, where the poet them/him/herself is the subject

(Figure D). As can be seen from these examples from Vivek Shraya, Morgan Robyn

Collado, Pat Califia, DarkMatter, Dane Figueroa Edidi and Xemiyulu Manibusan

Tapepechul, the self-presentation is designed to highlight a singular identity

as genderqueer and/or trans*. These photographs emphasise the writer's

completeness, self-awareness and comfort under (or in defiance of) the world's

gaze, something that suggests a journey either finished or at least having

reached a way station.

FIGURE A – Typographical covers

FIGURE B – Rhizomes, holes, maps, lines of flight

FIGURE C – Abstract bodies

FIGURE D -

Portraits

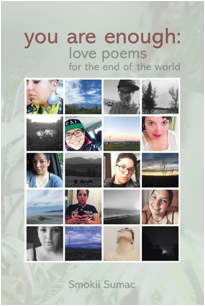

you are enough: poems for the end of the

world (2018), Smokii Sumac's debut collection, clearly stands at a distance

from all four of these possible trends. As in

Morgan Robyn Collado's cover,

reprinted here, the poet becomes his own subject in a number of poses. But

where Collado's photos are staged performances of her identity as a LatinX

working-class femme, Sumac's are candid and seem like a collage of personal photographs.

Unlike almost any other trans* poet that I have been able to find, Sumac's

cover—which he confirmed in our interview he was heavily involved in

designing—does not frame the body as either in a state of becoming via

abstraction, or in a state of arrival via decisive self-presentation to the

camera. Rather, these photographs create a multi-faceted and intimate portrait,

with Sumac presenting in different shots as butch, femme, Indigenous,

white-passing, playfully queer, or serious. The flatness of the format and the

non-chronological sequencing of the images means that no identity is

privileged, with the possible exception of the first top left photograph of

Sumac wearing some particularly gorgeous "watercolor earrings" by Navajo

jeweller Meek Watchman, which clearly signify as American Indian art and hence

emphasise indigeneity.[5] Certainly

there is no sense of a journey with either definitive start point or

destination. Instead,

the interleaving of photos of landscape and natural features declares a more

definitive sense that the poet has nowhere to travel to, since he already

belongs to this Indigenous land.

Morgan Robyn Collado's cover,

reprinted here, the poet becomes his own subject in a number of poses. But

where Collado's photos are staged performances of her identity as a LatinX

working-class femme, Sumac's are candid and seem like a collage of personal photographs.

Unlike almost any other trans* poet that I have been able to find, Sumac's

cover—which he confirmed in our interview he was heavily involved in

designing—does not frame the body as either in a state of becoming via

abstraction, or in a state of arrival via decisive self-presentation to the

camera. Rather, these photographs create a multi-faceted and intimate portrait,

with Sumac presenting in different shots as butch, femme, Indigenous,

white-passing, playfully queer, or serious. The flatness of the format and the

non-chronological sequencing of the images means that no identity is

privileged, with the possible exception of the first top left photograph of

Sumac wearing some particularly gorgeous "watercolor earrings" by Navajo

jeweller Meek Watchman, which clearly signify as American Indian art and hence

emphasise indigeneity.[5] Certainly

there is no sense of a journey with either definitive start point or

destination. Instead,

the interleaving of photos of landscape and natural features declares a more

definitive sense that the poet has nowhere to travel to, since he already

belongs to this Indigenous land.

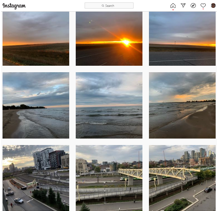

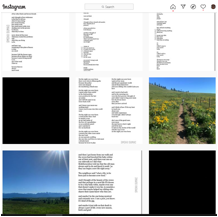

Significantly for the discussion in this article, the grid of squares

pattern is also very reminiscent of the Instagram platform. Indeed, some of the

photographs show up as posts on Sumac's publicly available Instagram account.

Instagram also gives further evidence of the fact that he takes great care over

visual as well as verbal self-presentation, as the following screen shots of

artfully staged and arranged photographs attest:

Sumac, as a

millennial and digital native, is at ease with the visual grammars of the

internet, and his Instagram presence shows some familiarity with the specific

form that poetry has taken in the social media age, while the cover design

analysed above demonstrates the interpenetration of social media and poetic

presences. In itself this is not surprising: Sumac is a millennial writer,

after all, and it is almost part of the job description for a modern poet to

keep their social media game on point. However, as I indicated in the

introduction, such digital spaces are far from neutral.

Being Two-Spirit and Trans* Online

Something most cisgender people

won't know about, when they read this story, is the wealth of knowledge and

connection that the internet has given transgender people (and Indigenous

people, for that matter, and I'm sure there are many other people who face

different forms of oppression who can say the same.) (Sumac, "Just Make Me Look

Like Aquaman")

There

is a surprising lacuna concerning digital spaces in Jack Halberstam's otherwise

comprehensive discussion of gender variability, Trans* (2018). Although he thoroughly discusses issues such as the

perceived tensions between radical feminist ideology and trans* identities, the

difficulties of representing the transitioning body, and the challenges that

trans* identities throw up for concepts of family relationships, the digital

landscape is mentioned only briefly and always in dismissive asides. Indeed,

Halberstam seems to find anything to do with the internet annoying: the fact

that "today Facebook famously offers you fifty-one ways of identifying yourself

on their site" (6) comes in for some mockery, while in a chapter on the

difference between the various generations of trans* people there is a clear

resistance to pesky youngsters "increasingly discover[ing] information about

themselves online" rather than learning directly from older activists now seen

as "as potential predators [...] and viewed with suspicion" (64). This may

reflect a changing dynamic in the 21st century. Surgical and

hormonal interventions to correct and reassign gender have been available

throughout the 20th century, beginning with Karl Meir Baer's

pioneering surgery in 1906, and continuing through such cases as Alan L. Hart

and Michael Dillon, while trans* people have been recorded throughout human

history, including ceremonial or sacred third gender roles such as the Omani khanith, Indian hijira or Thai kathoey.

But as Halberstam observes:

If I had known the term

"transgender" when I was a teenager in the 1970s, I'm sure I would have grabbed

hold of it like a life jacket on rough seas, but there were no such words in my

world. Changing sex for me and for many people my age was a fantasy, a dream,

and because it had nothing to do with our realities, we had to work around this

impossibility and create a home for ourselves in bodies that were not

comfortable or right in terms of who we understood ourselves to be. (1)

Given this history, it is easy to see that the digital

interconnectedness of the 21st century has changed trans* lives in

the West out of all recognition. As opposed to having to seek out specific

locations and subcultures usually based in heavily populated urban centres (for

instance the New York ballroom scene or the Polari-speaking drag cultures of

1950's London), young trans* people are now easily able to connect with one

another across the planet, to inform themselves about gender dysphoria and

their legal rights, and to investigate multiple possible modalities of trans*

expression. In previous decades the common trope of being "born in the wrong

body" continued to reinforce a binaristic view of sex, in that the trans* body

was seen as an error of biology that could be corrected, with the surgically

altered body sent out to fulfil a destiny as a now heterosexual woman or man

(it should be understood that I am discussing public perception here, not

reality). But with the coming of the internet and its potential for building

communities of often anonymous yet like-minded people, new potentialities for

trans* figuration came into view. As one of Richard Ekins and Dave King's

informants, Janice, puts it, "It was the Internet effect: that no matter how

small a minority you belong to, you could at last find your community" (28).

Andre Cavalcante makes the point that in the digital age transgender people

have had "access to hundreds of transgender themed websites, online forums, and

chat rooms in seconds," and that as such the digital world has formed a

welcoming space for trans* people to experiment with different identities

(114). Indeed, the internet is "central to surviving and thriving" for trans*

people, Cavalcante argues, as it is often easier to work, date and just hang

out in virtual spaces, which provide space not just for big issues such as

"gender reassignment surgery and political advocacy," but also for "the

smaller, mundane issues that define everyday life such as clothes shopping"

(117; 119).

Sumac clearly participates in such digital economies. In one poem, for

instance, he describes himself as a "trans tribe grindr dream" (33), while in

another he mentions learning from the online magazine Autostraddle, while yet another mentions "Chase Ross, youtuber and

trans 101er" (36), referring to the author of a Youtube series that includes

such titles such as "Pre-packed Underwear for Trans Masc Folks (GMP) Review"

(2019). The entire poem is even dedicated to a web company, Transthetics, which

manufactures products for transmasculine men. Such positioning in virtual

spaces does not only take place in poems focussed on transition. Advocacy and

political work for First Nations and environmental causes also requires

investment in digital identities. So one poem mentions, for instance, the

hashtagged campaign for "#justiceforcolten," referring to the campaign

following the acquittal of Colten Boushie's murderer (43), while others mention

"Trying to stay offline / news i can't look away from" (52), and a morning

routine where the poet needs to "block a few people / unfollow more / politics"

(91). More significantly, the entire collection is structured into six

sections, each titled with a hashtag – "#nogoseries": "#courting";

"#theworld"; "#recovery"; "#ceremony"; "#forandafter" – suggesting a view

of the world heavily mediated by social media experience. Additional evidence

comes in the form of an essay written by Sumac in 2015 about the #IdleNoMore

movement, in which he recalls "tweeting and Facebooking the hashtag along with

thousands of people across the world," and states that "For me, Idle No More created a sense of Indigenous

community that I had never been a part of before, and it did so through social

media" (98-99).[6] Although as

I will explore later in this article Indigenous identities have a complex

relationship to the digital world, Sumac clearly has found social media to be

as nurturing a space for First Nations collaborations as it is productive for

the development of trans* identities, as he explains in the quote that begins

this section.

However, if the digital landscape in Sumac's work is generally positive

and uplifting, that does not mean that there are no challenges to negotiate.

While the studies I previously quoted held that the online community of the

1990's and early 2010's contained revolutionary potential, others argue that

the effect of social media and increased trans* visibility has been to "unqueer" trans* discourse through a

fixation on narratives of passing (Siebler 81). Kay Siebler, for example,

suggests that "Transgender bodies are discussed, displayed, and regulated much

more rigidly on the Internet than the physical bodies of others within the

queer community" (83). Some of the blame for this, Siebler suggests, can be

placed at the door of dating apps which prioritise physical description, on

chat room discourse which centres on shorthand such as A/S/L, and on companies

which seek to profit by selling products designed to assist in passing. We can

see ripples from these pressures in the four poems that finish the #courting

section of you are enough. The

section as a whole has been structured around questions of love, consent and

acceptance (particularly in the central poem "at 29 i lie naked on the beach

and think of you," to which I return below), finishing with the poem sequence "haiku

/ consent series or / #makesexgreatthefirsttime" (27-31), and its imperative to

"forget the bad sex / I want to read the good."[7]

The last sequence takes up a specifically trans* journey into sexuality, with

the first poem consisting of the speaker's first use of the app Grindr

following a name change and beginning HRT. In this interaction he is literally

reduced to a body part:

question \ \ ftm / / question

"do you have a penis or a vagina?"

question

"i love bonus hole boys" (33)

The four poems

seem to have been ordered in line with the poet's transition. In the first the

poet is a "bonus hole boy" who has his lover "slide into you" (the poem is

written in the second person). In the second he mentions purchasing a strap-on

harness as a replacement for one stolen by a previous lover, but specifically

ties it to a queer rather than trans* identity by mentioning learning how to

wear a harness from the magazine Autostraddle.

The third poem is a depiction of mutual erotic ecstasy ("we didn't even /

notice / the power was out"), while the fourth and final poem,

self-explanatorily titled "'do you want to take the Cadillac for a ride?': Or:

a love letter to Transthetics / the company that made my prosthetic dick,"

makes the speaker's pleasure in his new penis clear ("I look down // and I am

transformed" (36)).

Siebler

sees such narratives as reinscriptions of conventional ideas of gender. While

trans* visibility has increased, and there are many examples of entirely

positive representations of trans* experience in contemporary media, the

inherent reductionism of digital chatrooms feeds into a general emphasis on the

correction of the misgendered body. Siebler argues that "Today transgender

people see hormones and surgery as a way to 'pass' in a heteronormative world

that mandates a rigid gender/sex binary" (77), becoming willing and active

consumers within a capitalist model that sees trans* bodies as sites for

profit. Sumac's poem, in such a view, partakes of the fantasy that a

pharmacocapitalist product is necessary to transform and thus improve a person,

literally becoming an advertisement for a company where the owner, himself a

transman, promises that "where there's a willy, there's a way! :)" (Alix).

Chase Ross, the YouTuber Sumac mentions, is one among many who have posted

regular updates on their transition over a ten year period: such video series,

structured in part to fit the algorithmically-controlled environment of

Youtube, form a kind of spectacularisation and regulation of the ftm trans*

body.[8]

Sumac, too, confesses to having made – but not posted – a "this is my voice 1 month on T" video,

and to have spent much time on the trans* internet watching such transition

videos. Where Susan Stryker sees a potential in trans* studies to "denaturise

and dereify the terms through which we ground our own genders," the digital

world has in Siebler's reading ended up re-reifying precisely those concepts of

gender that emerged from the Enlightenment period of taxonomisation that is so

bound up with colonial and imperial thinking (63). To say this is not in any

way to invalidate trans* personhood, but it is to ask whether trans* identity

is not itself in danger of being colonised by an overly medicalised capitalist

discourse which uses marketing techniques to externalise and "solve" a specific

mode of being. If Sumac's aim in you are

enough is to find a way to a poetic identity that is not only

transmasculine but also "queer bright / ktunaxa and proud / two spirit," with

that poem's implied challenge to whitestream cultures, then this flattening of

potential represents a real danger to his project.[9]

Sumac's resistance to this discursive reductionism can be seen at the end of

"'do you want to take the Cadillac for a ride?'" where the speaker's transition

is not in fact achieved with a prosthetic, but rather with a sexual connection

to another person – "and with her, I am transformed" (38).

A similar issue might exist with the sense of "Indigenous community" that Sumac found through

social media and hashtag activism. The phrase, which also turns up a lot in

discussion of the similarly internet-boosted #NoDAPL protests, carries inherent

challenges in its singularity, given the wide diversity of Indigenous cultures

found in North America. Gerald Vizenor, for one, has warned frequently and

loudly of the dangers of collapsing all tribal identities into a single indian signifier: however, in this case

the pressure is less one created in the self-justifications of settler

societies, and more the result of a specific and ever-narrowing tendency of

digital spaces towards monoculture. As of 2020, most of the top social media

sites most visited from the Canadian region (e.g. Instagram, Twitter, or

YouTube) use some form of algorithm to rank and prioritise content, as do

commercial sites such as Amazon. (Wikipedia, the main searchable source of

algorithm-free information, has its own issues with a non-diverse editor base.)

This environment introduces an inevitable and systemic set of biases. The

racist and misogynistic potentials of Big Data processing have been

comprehensively covered by researchers such as Safiya Umoja Noble, who notes

that many "algorithmically driven data failures [...] are specific to people of

color and women" (4). But the more subtle and insidious effect of social media

is in the filtering and narrowing of experience and of the potential for expressions

of difference in communal "bubbles" defined by a high degree of social

homophily, especially in the context of a platform designed to maximize user

engagement via manipulation of dopamine release in compulsion loops (Deibert

29). In the context of First Nations cultures specifically, there is a

potential danger of a loss of cultural diversity within a heavily online group,

driven away from tribal plurality by the algorithm into a pan-Indian average of

user preferences.

There is a specific danger for Indigenous

Two-Spirit youth in the existence of highly stratified digital spaces,

moreover. This is exemplified at the start of Joshua Whitehead's novel Jonny Appleseed (2018). The eponymous

Jonny, "Two-Spirit Indigiqueer and NDN glitter princess," moves in the first

two pages from masturbating over late-night silent pirate TV showings of Queer as Folk, through listening to "Dan

Savage and Terry Miller on the internet telling me that it gets better," to hooking up on the internet via "Facebook and

cellphones [and]... chatrooms on a gaming website," to "the photo-sharing apps

and cam sites" that allow him to make money as a virtual sex worker (7-8).

While the internet has allowed him to self-actualize, it also leads to his

leaving the reserve—where he has been the subject of homophobic abuse and

assault (91-92)—and operating in a Grindr world of non-Natives that

constantly fetishize his First Nations citizenship ("everyone on that damn app

was obsessed with New Age shit like [...] hipster shamans who collect crystals

and geodes looking for an NDN to solidify their sorcery"(18)). As in Sumac's

poetry, the digital therefore becomes a space that is both appealingly

accepting and potentially threatening both to tribal autonomy and also tribal

nations' cultural integrity. How Sumac navigates this challenge from online

no-space will be the subject of the final part of this article, but for now I

want to turn to a third area in which the digital space may be said to influence

production—in this case not just to content but also to form.

The poetry of likes

The popularity of poetry on social

media, particularly Instagram, in the past decade has been unprecedented. While

popular poetry has always existed, the sales of poets who first came to

prominence via the Instagram platform have been incredibly strong, especially

in the case of previously unknown writers. The standout is Rupi Kaur, whose

collections milk and honey (2015) and

the sun and her flowers (2017) have

not left the Amazon top ten list for poetry sales since publication. Her

publisher, Andrews McMeel, has become a central player in poetry publishing,

having published collections by r h sin, Amanda Lovelace, Courtney Peppernell,

Najwa Zebian and Pierre Alex Jeanty among many others. Often these writers are

labelled "Instapoets," a term that both recognizes their emergence from the

Instagram platform and also serves to denigrate much of their writing as

instant and disposable—for this reason, the label is frequently rejected

by poets such as Lang Leav (Shah). However, there are commonalities in this

group beyond their mode of production.

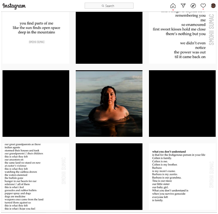

Posts to the Instagram platform

depend on visual appearance for gaining likes and shares. The power of the instant

feedback loop such likes provide can be seen in the fact that Instagram

executives in 2019 felt the need to begin hiding likes on accounts based in

Canada, in a bid to protect the mental health of its users (Yurieff). As

mentioned before, such likes have a physical effect in the dispensation of

dopamine, and it seems reasonable that this would affect poetic practice,

encouraging writers to reach as wide an audience as possible by removing

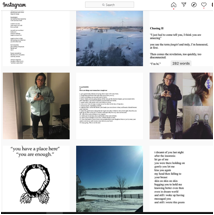

complexity from their work. The Instagram feed of Tyler Knott Gregson, where he

has published over 3,000 typewritten poems and almost as many daily

calligraphed love haiku, shows the rote mechanical effect of such a practice

(this is only a short excerpt):

Gregson is unashamedly commercial, as are his fellow Instapoets r.h. sin

(Reuben Holmes) and r.m. drake (Robert Macias), the latter of whom in fact

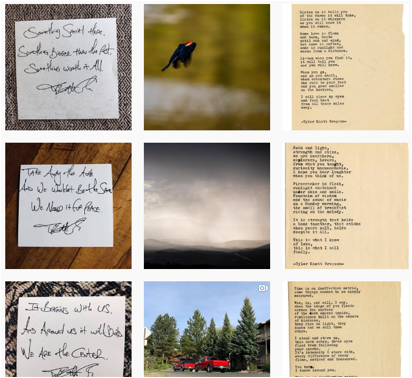

denies that he is a poet at all. A better example of the pressure to produce

particular types of content can be seen in the Instagram feed of the Dené poet

Tenille Campbell, who Sumac name-checks as an inspiration in finding self-love

(36), and with whom Sumac collaborated on the essay "Just Make Me Look Like

Aquaman." Campbell, a photographer as well as an academic and poet, curates her

feed to alternate between images usually drawn from nature, and short poems, as

in the screengrab below:

If, crudely, the success of a poem on

Instagram can be judged by the number of people inspired to demonstrate that

they like it by clicking a heart icon below the poem, then it is very

noticeable that the longer and more complex nature poem at the top of this

selection had garnered only 403 likes by the 3rd August 2020, and

the poem at the bottom with the racial signifiers gained 749. The middle poems,

on the other hand, with their lack of specificity and superficially feminist

message, had scored 834 likes for the right-hand poem and 1,136 for the one on the

left. In other words, the more the poem fits an image of a self-empowered and

sexually autonomous woman, the more cultural capital it accrues—and,

unlike previous generations of writers, social media poets receive such

feedback in real time. As Millicent Lovelock remarks in a conference paper, à

propos Rupi Kaur:

her

frequent use of simple, direct, and unambiguous language on the subject of

trauma and healing can be understood [...] as a reproduction of a pervasive

neoliberalism which centres the self as a site of labour and ignores the

specific societal conditions which might produce trauma.

Instagram's machine learning generated algorithm prioritizes posts for

display that other users are more likely to "like," based on a complex series

of factors including who else has already liked those posts or other posts by

the same user with similar hashtags. The effect for any one writer on any one

poem is arguable at best, but the overall pressure is undeniable. And this is

not just true as regards content, but it also applies to form. Instapoets

specialize in short poems that are brief and direct, such as the haiku—at

least, the anglicized version of the haiku, which requires only attention to

syllable count and often does not pay attention to the Japanese form's requirement

for kigo or kireji—and simple free-form verses formed from one or two

sentences with little or no attention paid to metrical patterning.

Facebook,

where Sumac's poetic journey began, differs from Instagram in that there is

less of a visual element and users are mostly only broadcasting to "friends"

and followers on the site (hashtags being only a small element of Facebook

interaction), meaning a more focused audience, but the pressure towards small

word counts and direct statements exerted by the "like" function and by the

requirement to generate a poem for public consumption per day still remains.

Some of Sumac's poems certainly have the direct simplicity of Instapoetry, as

in this example:

offer

what i can

but emotional labour

takes its toll

rest now (61)

Or

this:

"we have everything we need"

when you said it that first time

it took everything to try and believe

but when i woke up today

angry that they tried to make me forget it

i think i understand

i am everything i need (67)

Claire Albrecht coins the term "therapoeia" to describe the trend of

social media poetry, driven by the pressures outlined above, towards "readymade

self-love and acceptance," particularly poetry created by millennial and Gen-Z

writers in Western societies among whom levels of anxiety and depression are at

an all-time high (Albrecht). Sumac, who devotes one of the six sections of the

book to "depression and addiction" and who has been open about his own

struggles with such conditions, certainly enters this mode many times. These

fragments are not presented as discrete poems, and this fact forces them into

dialogue with the greater complexities of identity and belonging in other poems

in the collection: nonetheless, their existence demonstrates that Sumac's

poetry is subject to some of the flattening of affect observed in Instapoetry.

While the digital environment that shaped his early poems certainly has not had

a completely deadening effect on his writing (one only needs to compare Sumac's

syllabic control to the free-form chopped-up prose of a Courtney Peppernell to

see this), certainly it makes sense to situate him within this community of

digital creatives.[10]

As with the previous discussions of

online trans* and pan-Indigenous communities, it is not my intention to

demonize social media poetry. Not only is poetry publishing globally in a rare

rude state of health following the success of the Instapoets, but the genre has

created an opening for voices who have rarely been at the forefront of English

language writing in settler cultures. Young female voices of colour from

immigrant communities are particularly strongly represented, including Rupi

Kaur (born in India), Najwa Zebian (Lebanon), and Lang Leav (Cambodia), none of

whom, crucially, centre their writing on their experience as ethnic or gender

minority subjects. As Leav pointed out to me in an email, the seemingly

unmediated level of access provided by social media has also allowed for a

generation of working class voices to be appreciated by a wide audience, where

such voices might have been either excluded or ghettoized. It might also be

observed that the "perform your truth" ethos of the new poetry (which also owes

something to slam poetry events) benefits writers like Sumac, and other trans*

poets on Instagram such as Mia Marion and Hunter Davis, in creating an audience

willing to appreciate and celebrate his identity as a queer, nonbinary,

transmasculine, Ktunaxa citizen. However it is obvious that an uncritical set of

therapeutic generalities also carries the danger of forming what Lauren Berlant

calls an "intimate public": a body of sentimental texts bound by a common

recognition of pain, which gives its readers "permission to live small but to

feel large; to live large but to want what is normal too; to be critical

without detaching from disappointing and dangerous worlds and objects of

desire" (Berlant, loc 197). Such an intimate public is "juxtapolitical" (loc

103) rather than political, usually expressing a desire to return to the

conventional—one can see how the hashtag #justiceforcolten might not

easily garner likes within the bright and happy space of Instagram in the same

way it can do on Twitter.

This is where Sumac can be clearly

differentiated from the crowd of Instapoets, for you are enough is by no means purely in the mode of therapoeia, and

it certainly does not always insist on establishing commonality. To explain, I

compare two representative poems.

The first is from Atticus, a leading Instapoet:

Don't fear, her

father said,

sometimes

the scary things

are beautiful as well

and the more beauty

you find in them

the less scary

they'll become. (loc. 737)

We are not told

who the anonymous "you" of the passage is, but there seems little from the

context to suggest that this is a specific person. Rather, as with the

omnipresent "you" in r.h. sin's poems, this is a generic female addressee given

as few markers as possible, the better to provide a blank space for the (coded

female) reader to identify with. By contrast, here is a typical excerpt from

Sumac on the same subject:

when the rest of the world grieves for a world they

think is gone,

when we've awoken to a nightmare we didn't think was

possible,

when i am afraid that i can't make it to the next

sunrise and i

don't know if the tears will ever stop,

when smiling seems like it might be

a failure.

on days like these i find strength in your

presence—

like a lighthouse on fire in a storm i

couldn't find my way out of alone.

You once told me the kitchen floor is the best place

to cry;

("there are hierarchies of grief,"

46)

Both poems deal

with finding the strength to move through difficult emotions. However Sumac's

poem is a threnody dedicated to specific people, as evinced by the precise

details that collect throughout—"your generosity flowing from fingertips

on that piano you don't play." These form a private set of symbolic images,

which cannot be fully comprehended by anyone who does not know the intimate

details of the relationships being shown. Indigenous signifiers threaded

through the poem ("i think of how you taught me to carry and take care of / the

feathers" (47)) also explain what is meant by the titular hierarchies of grief,

how the individual's grief is given context and weight by wider griefs at the loss

of "a world." Here we see how Sumac's poetry, emerging from an online space,

nonetheless avoids the weightlessness of much social media poetry by engaging

with tradition and ethnicity embodied in natural imagery in phrases such as

"[you] showed me where your little star so / strong brought down a tree so we

could be with the / water" (47). And it is to water that I want to turn in the final

section of this article, to look at the ways that Sumac uses natural spaces and

ceremonial imagery to ground his poetry even in the digital context.

Smokii on the

water

The illustration

overleaf is a word cloud made up of all the words (including poem titles and

individual poem dedications but excluding acknowledgments, section titles and

copyright information) in the collection you

are enough.[11] Such word

clouds, as Samuels and McGann have argued in their article "Deformance and

Interpretation," continue the work of traditional criticism in deforming the

text to reveal and interpret hidden codings (152).

In the words of

Amanda Heinrichs, they "suggest both an immediate, impressionistic 'grokking'

of the underlying 'data patterns' of the thing they remediate and they invite

the reader to perform the searching, delicate, sometimes-clumsy work of

meaning-making that is close reading" (408). Certainly such digital methods

seem appropriate to an author whose practice I have argued is very much bound

up with digital contexts. And indeed a list of the most common words in Sumac's

writing, in order of frequency, practically becomes a new poem in its own

right:

|

Word |

Weight |

|

now |

82 |

|

like |

76 |

|

just |

61 |

|

love |

58 |

|

time |

53 |

|

know |

52 |

|

will |

51 |

|

one |

45 |

|

can |

44 |

|

see |

41 |

|

still |

39 |

|

think |

39 |

|

enough |

33 |

|

way |

32 |

|

back |

31 |

|

First |

31 |

|

Home |

30 |

This "tabular

poem" already shows the simplicity of language in Sumac's poetry and its major

themes of desire and the (re)claiming of space as home. A look at the full

database confirms this initial impression: the vast majority of words are

common monosyllables, and the primary verbs almost all express either emotion

or introspection for personal growth ("love," "know," "think," "feel," "need,"

'breathe," "learn"). But a second word cloud, this time concentrating on nouns,

is more revealing:[12]

Many of the

most significant words of the collection, as can be clearly seen, are to do with

time and seasonality. In particular, the combination of "moon," "time," (and

time-related words such as "today," "day," "night"), "heart" and "body" show, I

believe, Sumac's investment in a cyclical temporality and in images of renewal:

one poem-fragment reads, for example, "this will be last time / the next time

we come" (20). The frequent use of "way" and other travel signifiers also show

that Sumac, a poet who is deeply invested in ideas of home, sees being "at

home" not as stasis but as a form of movement, often in the form of interior

development. Of course, these sentiments are shared widely in therapoeic social

media poetry. Take, for instance, this untitled poem by r.h. sin, though there

are an almost infinite number of possible examples:

More interesting is the prominent appearance of the word "moon". Another

excerpt from Sumac's poems demonstrates the personal symbolism behind this

word:

and so i chased the sunset driving against my instinct

back east and

south and up that big hill past the teaching lodge where i went to my

first full moon ceremony to pray for the journey this body was about to

start

While the moon

functions as a female symbol in many cultures, frequently due to a cultural

association between menstrual and lunar phases, here Sumac relates such natural

cycles to his transition to masculinity. As he puts it in his article "Just

Make Me Look Like Aquaman": "The gender binary has consumed my ability to

understand that the moon is not judging me; I am. The moon still shows her face

to me. The moon still holds me like the tides." The same article also states

that this was his only full moon ceremony, implying a potential goodbye to

femininity.

As can be seen from the second word cloud above, other words relating to

natural phenomena ("skin," "sun," "fire," "blood") are used frequently in his

writing, nowhere more so than in the "#ceremony" section, in which poems on

just the first page celebrate "the kiss of the prairie moon," "river rocks" and

"tap[ping] the snow off cedar" (85). Such use of natural imagery within a

ceremonial context serves to ground Sumac's writing in a specifically

Indigenous, land-based system of belief, and acts as a strong counter-measure

to the digital flattening effect traced above. It is also significant that in

his poems Sumac gives very few details about the actual ceremonies. This

honours the spiritual imperatives against sharing with outsiders common across

pan-Indian religions, allowing Sumac instead to discuss the spiritual and

ethical lessons learned from the land ("the mountains told me / carry knowing

in your body (92)).[13]

For a special issue primarily concerned with trans* and Two-Spirit

writing, perhaps the most significant natural symbol Sumac uses—another

word that is repeated frequently—is "water." This focus on water imagery

may reflect elements of Ktunaxa cultural understandings and/or Ktunaxa

politics, as like many First Nations the Ktunaxa government are often in

negotiation with settler authorities for de

jure and de facto access to and

use of waterways within their ancestral homelands (see, e.g., Locke and

McKinney 204). More, it should be remembered that the collection was written in

the shadow of the protests against the Dakota Access Pipeline, hashtagged

#noDAPL, in which the Standing Rock Sioux and their allies argued that the

proposed (and now operational) oil pipeline represented a serious threat to the

tribal nation's water supply and to waterways guaranteed under treaty, so water

was a major element of pan-Indigenous discourse at the time. However the poem "at 29 i lie naked on

the beach and think of you" (24), perhaps the most confrontational piece in the

entire collection, shows that Sumac feels he has a more direct and intimate relationship

with water. In this poem, placed within the pivotal "#courting" section and one

of the first poems in the collection with a specified title, Sumac's speaker

remembers an ex-lover ("and i saw you on instagram smiling at pride. // you,

the baby dyke / that doesn't even like going down"). The speaker undresses himself on a beach and walks to the

water, observed by a voyeuristic older man who "just sits, his erection and my

knowing / between us," a form of attention that places him in a position of

power, and in fact seemingly empowers him towards the realisation that "i am

someone you could never understand." Although the "you" of this statement is

superficially the ex-lover, it also seems to be aimed at the reader and maybe

even contains a realisation for the speaker himself, as in the next line he

enters the cold water, which absorbs his tears of loss and anger. After a

momentary dissolution into pain, the speaker is reborn—an idea that,

Sumac makes clear, is not an uncomplicated one for an adoptee ("this gasp is

like the one i took bursting forth from the womb of a woman / who wouldn't even

look at me"). The poem ends with the speaker celebrating his "ktunaxa skin,"

buoyed up by the water.

The significance of this image-memory for Sumac can be seen in the fact

that, after entering transition, he re-staged the scene of stripping off and

entering the water in a photo-essay collaboration, ""Just Make Me Look Like

Aquaman": An Essay on Seeing Myself," which appeared on the blog "tea &

bannock" in February 2020.[14] Although

the voyeuristic male gaze is absent, Sumac in the series of photographs for

this piece is again being witnessed, this time by the photographer Tenille

Campbell, and again sees a bald eagle (mizigi) flying overhead. In a

progression of images, he disrobes and eventually faces the camera. In the

accompanying text, Sumac discusses harder truths about his life that are only

glanced at in the poems of you are enough—"the

molestation at 12, the rapes at 15, 17, 21"—which clearly underscore the

elements of rage and grief in the earlier poem. As in "at 29 i lie naked on the

beach and think of you," Sumac as "Aquaman" again conveys an experience of

transcendence, but this time frames it more academically in terms of overcoming

more familiar representations of Native American peoples in mainstream culture

("Too many people still want to photograph the Indians with their own Edward

Curtis-like agenda."). A transmasculine man, his breasts clearly on display,

standing thigh-deep in the ocean with his prosthetic penis touching the water,

is nobody's "vanishing" Chief Joseph: Sumac affirms his Two-Spirited

transmasculinity as being a native product of North American Indigenous lands,

a gesture of profound survivance.

Conclusion

At the

beginning of this article, I demonstrated the ways in which Sumac's art was

founded in, and is in some ways a product of, a digital landscape, particularly

of certain social media platforms. I argued that this landscape continued to

have an effect on the finished product, and that this could be seen in the cover

imagery, the actual form and language of the poems, and in some of the ways

that Indigenous and trans* themes were approached in the poems. I gave some air

time to the arguments of Kay Siebler, who argues that a loss of queer potential

was occurring through an algorithmically driven pharmacocapitalist environment

that enforced a new form of gender normativity for young trans* people, and

extended this discussion to incorporate concerns regarding the algorithmic

manipulation of Indigenous communities online and the flattening of affect seen

in popular poetry generated for a click and like economy. I am aware of the

risk that, being as I am a white male cishet Gen-X scholar born into privileges

of class, race, sexuality and gender, my negative feelings about social media

and changing identities may simply reflect the usual generational concerns

about a changing world and young people today, but I have provided evidence

from a number of different sources to justify this investigation. As someone

who is not Ktunaxa or First Nations, and cannot bring either detailed knowledge

or experience of ceremony to bear, I have also chosen to focus on those

elements of Sumac's poetry which particularly stand out to me, which I

acknowledge may also be a by-product of my having been in the limited digital

Facebook audience for early versions of some of his poems.

What the final section of this article begins to demonstrate, however,

is the way in which Sumac's work not only embraces all of the identities to

which I referred in the introduction, but also starts to weave them into a

coherent whole. Water and moon imagery, both universals but ones that carry

particular meanings in the poet's recovered Indigenous culture, serve as

springboards to assert a selfhood that can incorporate the poet's trans*

present and future without rejecting his female past, an Indigenous futurity

that does not ignore the poet's out-adoption and upbringing, a queer sexuality

that refuses to settle into a singular label. As such, it presents the

strongest possible challenge to Siebel's contention that the multiplicity and

potentiality of queerness is challenged by contemporary normative trans*

digital cultures, or similar concerns about the homogenising effect of digital

culture on Indigenous nations. I would also contend that Sumac's writing should

make us re-evaluate the practice of more mainstream/commercial Instapoets who

have emerged from the social media bubble. The hashtag is a potent organising

principle in Sumac's collection, both in the section names and in the

#haikuaday with which it began. It should also draw our attention to the

arrangement of the poems, where it is not even entirely clear where one

discrete poem ends and another begins. As with hashtags in the digital world,

the hashtags in Sumac's work serve to restructure the poems away from being

singular units and into becoming fluid and interlinked units of a larger

discussion, removing impediments to a free flow of energy and desire across his

writing. As such, it represents a potent evolution of Indigenous writing into

the interlinked realities of a digital world.

Works Cited

Abi-Karam, Andrea. Extratransmission. Kelsey Street Press, 2019.

Albrecht, Claire. "Therapoeia: The Hive

Heart of Online Poetry." Overland, 12

Jun 2018, https://overland.org.au/2018/06/therapoeia-the-hive-heart-of-online-poetry/

Alix. "About the Maker." Transthetics, https://transethics.com/about-the-maker.

Aoki, Ryka. Seasonal Velocities. Trans-Genre Press, 2012.

Atticus. Love Her Wild. Atticus Publishing, 2017, Kindle edition.

Benaway, Gwen. Holy Wild. Book*hug, 2018.

---. [As Gwendolywn Benaway]. "Ahkii: a

Woman is a Sovereign Land." Transmotion,

vol. 3, no. 1, 2017, pp. 109-138. https://doi.org/10.22024/UniKent/03/tm.374.

Berlant, Lauren. The Female Complaint: The Unfinished Business of Sentimentality in American

Culture. Duke University Press, 2008, Kindle Edition.

Brolaski, Julian Talamantez. On Mongrelitude. Wave Books, 2017.

Califia, Pat. Diesel Fuel: Passionate Poetry. Masquerade Books, 1997.

Campbell, Tenille K. [As

sweetmoonphoto]. Instagram feed. Instagram,

https://www.instagram.com/sweetmoonphoto/?hl=en.

Candrilli, Kayleb Rae. What Runs Over. YesYes, 2017.

Cavalcante, Andre. "'I Did It All

Online:' Transgender identity and the management of everyday life." Critical Studies in Media Communication,

vol. 33, no. 1, 2016, pp. 109-122, doi:10.1080/15295036.2015.1129065.

Charles, Josh. feeld. Milkweed, 2018.

Chrystos. Not Vanishing. Press Gang, 1988.

Collado, Morgan Robyn. Make Love to Rage. biyuti publishing,

2014.

Coman, Joshua. "Trans Citation

Practices: A Quick-and-Dirty Guideline." Medium,

27 Nov 2018, https://medium.com/@MxComan/trans-citation-practices-a-quick-and-dirty-guideline-9f4168117115.

Darkmatter. [Alok Vaid-Menon and Janani

Balasubramanian]. It Gets Bitter: Poems

by Darkmatter. Darkmatter, 2014, https://www.darkmatterpoetry.com/.

Deibert, Ronald J. "The Road to Digital

Unfreedom: Three Painful Truths About Social Media." Journal of Democracy, vol. 30, no. 1, Jan 2019, pp. 25-39,

doi:10.1353/jod.2019.0002.

Driskill, Qwo-Li. "Stolen From Our

Bodies: First Nations Two-Spirits/Queers and the Journey to a Sovereign

Erotic." Studies in American Indian

Literature, vol. 16, no. 2, 2004, pp. 50-64

Edidi, Dane Figueroa. Remains: A Gathering of Bones. No

publisher, no date, http://www.ladydanefe.com/remains-a-gathering-of-bones.

Edwards, Kari. having been blue for charity. BlazeVox, 2006.

Ekins, Richard, and Dave King. "The

Emergence of New Transgendering Identities in the Age of the Internet." In Transgender Identities: Towards a Social

Analysis of Gender Diversity, edited by Sally Hines and Tam Sanger.

Routledge, 2010.

Gould, Janice. "Disobedience (in

Language) in Texts by Lesbian Native Americans." Ariel: A Review of International English Literature, vol. 25, 1994,

pp. 32–44.

Gregson, Tyler Knott. [As tylerknott].

Instagram feed. Instagram,

https://www.instagram.com/tylerknott/?hl=en.

Halberstam, Jack. Trans*: A Quick and Quirky Account of Gender Variability.

University of California Press, 2018.

Heinrichs, Amanda. "Deforming

Shakespeare's Sonnets: Topic Models as Poems." Criticism, vol. 61, no. 3, Summer 2019, pp. 387-412,

doi:10.13110/criticism.61.3.0387.

Jennings, Melissa. Afterlife. CreateSpace Independent

Publishing Platform, 2017.

Kaur, Rupi. milk and honey. Andrews McMeel, 2015.

---. the sun and her flowers Andrews McMeel, 2017.

Ladin, Joy. Impersonation. Syracuse University Press, 2015.

Locke, Harvey, and Matthew McKinney.

"The Flathead River Basin." In Water

without Borders?: Canada, the United States, and Shared Waters, edited by

Emma S. Norman, Alice Cohen and Karen Bakker, University of Toronto Press,

2013.

Lovelock, Millicent. "Healing is

Everyday Work: Instapoetry, Intimate Publics, and the Language of Self-Help." Reading Instapoetry, University of

Glasgow, 14th-16th July 2020. Conference Presentation.

Mackay, James. "Sweatlodge in the

Apocalypse: An Interview with Smokii Sumac." Transmotion, vol. 6, no. 2, doi:10.22024/UniKent/03/tm.918.

McGann, Jerome, and Lisa Samuels.

""Deformance and Interpretation." In Poetry

& Pedagogy: The Challenge of the Contemporary, edited by Joan Retallack and Julia Spahr,

Palgrave Macmillan, 2006, doi:10.1007/978-1-137-11449-5_10.

Noble, Safiya Umoja. Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines

Reinforce Racism. New York University Press, 2018.

Pearson, Elijah. Ash. Poem Sugar Press, 2013.

Peppernell, Courtney. "The Road

Between." Instagram, 16 August 2020, https://www.instagram.com/p/CD9FXJxnZ3o/.

Philips, Xandria. Hull. Nightboat, 2019.

"Previous Winners." LAMBDA Literary, 2020, https://www.lambdaliterary.org/previous-winners-3/.

Priddy, Molly. "Why is YouTube

Demonetizing LGBTQ Videos?" Autostraddle,

22 Sept 2017, https://www.autostraddle.com/why-is-youtube-demonetizing-lgbtqia-videos-395058/

Ross, Chase. "Pre-packed Underwear

for Trans Masc Folks (GMP) Review."

YouTube, 28 Aug 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xfty_4gcslE.

Shah, Manali. "Poet Lang Leav talks

about being an unlikely social media celebrity." Hindustan Times, 25 Nov 2016, https://www.hindustantimes.com/more-lifestyle/exclusive-poet-lang-leav-talks-about-her-new-book-and-being-an-unlikely-social-media-celebrity/story-yHOJx4lxDIlwoBonJ1cclJ.html.

Shraya, Vivek. even this page is white. Arsenal Pulp Press, 2016.

Siebler, Kay. "Transgender

Transitions: Sex/Gender Binaries in the Digital Age." Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, vol. 16, no. 1, 2012,

pp. 74-99, doi:10.1080/19359705.2012.632751.

sin, r.h. i hope this reaches her in time. CreateSpace Independent Publishing

Platform, 2017.

Stallings, A.E. "Sestina: Like." Poetry May 2013. Poetry Foundation. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/poems/56250/sestina-like

Stryker, Susan. "Transgender

Feminism: Queering the Woman Question." In Third

Wave Feminism: A Critical Exploration, edited by Stacy Gillis, Gillian

Howie and Rebecca Munford, Palgrave MacMillan, 2007, pp. 59-70.

Sumac, Smokii. "Just Make Me Look Like Aquaman: An

Essay on Seeing Myself" Tea & Bannock.

2020. https://teaandbannock.com/2020/02/11/just-make-me-look-like-aquaman-an-essay-on-seeing-myself-smokii-sumac-guest-blogger/

---. [As smokiisumac]. Instagram feed. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/smokiisumac/.

---. "On Idle No More: A Review Essay."

Transmotion, Vol. 1, no. 2, Nov.

2015, pp. 98-105, doi:10.22024/UniKent/03/tm.198.

---. [As smokiisumac]. Photograph of

earrings. Instagram, 16 Sept 2016, https://www.instagram.com/p/BKikJ4vDdWA/.

---. "Two Spirit and Queer

Indigenous Resurgence through Sci-Fi Futurisms, Doubleweaving, and Historical

Re-Imaginings: A Review Essay". Transmotion,

Vol. 3, no. 2, Dec. 2017, pp. 168-75, doi:10.22024/UniKent/03/tm.447.

---. you are enough: love poems for the end of the world. Kegedonce,

2018.

Takács, Bogi. "Poetry Collections by

Trans / Nonbinary / Genderqueer Etc. Non-Cis Authors (157 Books)." Goodreads, 20 Jan. 2017, www.goodreads.com/list/show/107863.Poetry_collections_by_trans_nonbinary_genderqueer_etc_non_cis_authors.

Tatonetti, Lisa. "The Emergence and

Importance of Queer American Indian Literatures; or," Help and

Stories" in Thirty Years of SAIL."

Studies in American Indian Literatures, Vol. 19, No. 4, Winter 2007, pp.

143-170, doi:10.1353/ail.2008.0013.

Tapepechul, Xemiyulu Manibusan. Metzali: Siwayul Shitajkwilu {Indigenous:

Heart of a Womxn Writing). CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform,

2018.

Thom, Kai Cheng. A Place Called No Homeland. Arsenal Pulp

Press, 2017.

Tolbert, TC, and Trace Peterson. Troubling the Line: Trans and Genderqueer

Poetry and Poetics. Nightboat, 2013.

Valerio, Max Wolf. The Criminal: The Invisibility of Parallel

Forces. EOAGH Books, 2020.

Vernon, Ashe, and Trista Mateer. Before the First Kiss. Words Dance,

2016.

Watchman, Meek. "Aerial Poet: Artist

Statement." Meek Watchman, no date, http://meekwatchman.com/artist.

Whitehead, Joshua. Jonny Appleseed. Arsenal Pulp Press, 2018.

---. "Why I'm Withdrawing From My

Lambda Literary Award Nomination." TIA

House, 14 Mar 2018, https://www.tiahouse.ca/joshua-whitehead-why-im-withdrawing-from-my-lambda-literary-award-nomination/

Wordclouds, https://www.wordclouds.com/.

Yanyi. The Year of Blue Water. Yale University Press, 2019.

Yurieff, Kaya. "Instagram is now

testing hiding likes worldwide." CNN,

14 Nov 2019, https://edition.cnn.com/2019/11/14/tech/instagram-hiding-likes-globally/index.html