The

Crisis in Metaphors:

Climate

Vocabularies in Adivasi Literatures

ANANYA MISHRA

Kuni Sikaka, Arjun Samad, Dodhi

Kadraka, Manisha Dinde

Adivasi Lives

Matter, a social media forum for young

Adivasi thinkers, shared these four names listed above, following recent arrests

of climate activists in India ("Young Adivasi").

The forum extended their solidarity and raised their voices against the detainment

of Disha Ravi. It remembered and recognised the contributions of young Adivasi

climate activists who have resisted industrial invasions and have been

similarly arrested or incarcerated for demanding protection of their ecologies.

Adivasi voices on climate action remain largely marginalised, while Adivasi

communities have steered and sustained "this battle" for climate justice "for

generations" ("Young Adivasi")

in the Indian context. The forum's timely reminder adds vigour to a global

Indigenous concern: that the current form of the climate crisis is largely

anthropogenic, and to comprehend and repair the interface between humans and

non-humans is paramount for a sustainable future, a point that has been

consistently articulated by Indigenous thinkers. Métis scholar Zoe Todd claims precisely that the

absence of Indigenous voices in framing the crisis, while being the most

vulnerable to its impact, "elide[s] decades of Indigenous articulations and

intellectual labour to render the climate a matter of common political concern"

(Todd 13). Indigenous knowledge systems of the non-human that are based on the

essential co-existence of humans and non-humans, with lived practices that

acknowledge "all our relations", are overlooked. Akash Poyam, a Koitur (Gond)

journalist and writer, articulates allied concerns for the absence of Adivasi

voices in the Indian context. In an online panel discussion organized by

Indigenous Studies Discussion Group (ISDG), he said, "Even though Adivasis are

said to be in the frontline of the crisis, their voices are not there in the

discourse. It is an upper-caste dominated environmentalist discourse" (Poyam,

Soreng, et al.).

Questions

raised by Poyam and Adivasi Lives Matter reveal the position of Adivasi

voice in climate discourse which, as I consider in this paper, mirrors the

precondition of Adivasi voice in the humanities. As the perpetual subaltern in postcolonial

literary studies, Adivasis "[embody] the limits of representation as the limit

horizon of modernity itself" (Varma "Representing" 103). Adivasi

voices are still accessed either through the "imperial copy"[1]

of ethnographical disciplines like folklore, or the subaltern in

representational narratives.[2] This is while

a thriving movement towards an Adivasi "self-governing literature" (Wright,

"The Ancient Library")[3] has been

ongoing since the early twentieth century. The archived speeches of Jaipal

Singh Munda and the poetry of Sushila Samad are testaments to this history. The

writings of Bandana Tete, Alice Ekka, Ramdayal Munda, and Hansda Sowvendra

Shekhar, the poetry and songs of Jacinta Kerketta, Bhagban Majhi, Dambu Praska

and Salu Majhi, among many others, and the thriving archives of adivaani,

Adivasi Resurgence and Adivasi Lives Matter, voicing ongoing land

dispossession and lived positions in contemporary India, command critical centring

in the climate discourse as well as in postcolonial literary studies. This

positioning cannot be limited to the area-specific context of South Asian studies

alone. Adivasi voices challenge the global industrial complex, and their

concerns echo those voiced by Indigenous communities in settler colonial

contexts (mining giant Adani, for instance, impacts Indigenous communities in

India and Australia). Indigenous critical theory from settler colonial contexts

that complicates or rejects the postcolonial (Corr, 187-202; Tuck and Yang,

1-40) critically positions the centrality of land for Indigenous communities.

Accordingly, it re-directs discourse to understand the Adivasi position within

the postcolonial nation. It revisits Adivasi demands for sovereignty as

separate from its appropriations within Indian nationalism and recognizes

settler practices replicated by the Hindu nationalist state. Besides,

foregrounding Adivasi voices in transnational Indigenous studies allows for a

reading of "literary sovereignty" or "sovereignty of the imagination" in

Adivasi literature alongside those ideas envisioned and theorized by Alexis

Wright, Simon Ortiz, and Robert Warrior.[4]

My use of the word "sovereignty" in this article is to evoke these essential

linkages.

By

method and readership, this paper addresses comparative literary studies. However,

given the composite forms of Indigenous thought that interweave the literary

and the historical, the paper is interdisciplinary, and hopes to present

relevant questions across disciplinary boundaries. Thus, it is divided into

three sections. First, I discuss the position of Adivasi voices in literary

studies in relation to the wider problematic of the absence of Indigenous voices

while framing the climate crisis and the Anthropocene.[5]

Further, this section explores a literary methodology to recover early

Indigenous response to the crisis. Rob Nixon echoes a call for a return to

metaphors, thus: "Sometimes [metaphors are] just hibernating, only to stagger

back to life, dazed and confused, blinking at the altered world that has roused

them from their slumber" ("The Swiftness"). I claim that Indigenous literatures

hold early warnings of the climate crisis in metaphors we do not yet centre in

climate discourse. The second section examines the climatic processes

(meteorological and anthropogenic) that have radically altered the climate of

eastern India. Although my focus is on the historical context of Odisha

(eastern India), I draw from a wider range of resources, given that these

processes, and their consequences, are not limited to the present-day borders

of Odisha alone. Accordingly, this paper claims that early warnings of a "crisis"

were registered in the recurrence of concerns around jal, jangal, jameen

(linguistically translated as water, forests, land) from the late nineteenth

century onwards. Jal, jangal, jameen is a ubiquitous refrain in diverse

Adivasi movements. These vocabularies work as a "common organizing concept" (Todd,

5-6) for Adivasi concerns because they evoke a common climatic history.

Moreover, they encompass specific non-humans in the ecologies of jal, jangal,

jameen interconnected with Adivasi knowledge systems. The third section

provides literary readings of Adivasi songs emerging from the particular

geography of southern Odisha. Focusing on particular ecologies of Kashipur and Niyamgiri,

I examine the songs of Kondh poet Bhagban Majhi (Kashipur), and late Dongria

Kondh poet Dambu Praska (Niyamgiri). The two singers pay attention to local

markers and traces in ecology to assess climate breakdown following industrial

invasions by Utkal Alumina International Limited (UAIL), Aditya Birla, and

Vedanta. I read how their literary metaphors serve as archives of

interpretations of the climate crisis as already confronted in these

geographies.

I.

The

Crisis in Metaphors

In The Great Derangement: Climate Change

and the Unthinkable, Amitav Ghosh writes: "it was exactly the period in

which human activity was changing the earth's atmosphere that the literary

imagination became radically centred on the human" (66). There was a general "turning away" from the "presence

and proximity of non-human interlocutors" during the Industrial era, and in

recent decades the concern has found a rejuvenation with an "interest in the

nonhuman that has been burgeoning in the humanities", together with the rise of

"object-oriented ontology, actor-network theory, the new animism" (31). On this

phenomenon in literary studies, Stephen Muecke writes in his review of Timothy

Morton's Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World,

that "postmodernism has returned with a vengeance, bolstered with all the moral

force of global ecological concerns" (Muecke, "Global Warming", np). While reading Ghosh, Todd, and Muecke's respective

works, I gleaned two corresponding strands of thought: as in the history of

philosophy that centred the human, this "renewal" of engagement with the

non-human too is yet again overpowered by the position of its production—one predominantly representative of the global North, and particularly the

Euro-American man. From this positionality, literary fascination with climate

crisis and the non-human, can claim postmodern newness to the extent of having

rationally discovered relevance of the concepts themselves, solely by the

virtue of occupying the discourse position of the Euro-American centre. For

communities, and their histories deemed "unthinkable" (referred to in the sense

of Trouilliot's "unthinkable history")[6],

literary studies has yet to centre Indigenous literary traditions as literary

beyond the reams of anthropological proof. That Indigenous communities may have

articulated early forms of the crisis still remains in the realm of the "unthinkable".

It is precisely a "crisis of the

imagination" (Ghosh, 9) that has foreclosed a literary reading of Indigenous

philosophies of the non-human and of Indigenous articulations (oral and

written) that intimated the crisis. When Indigenous land, people, or artistic

practises are referred, if at all, they create the "hypersubject" (Muecke, "Global Warming", np). Peripheral geographies and the oppressed

on the peripheries of the enquiry are called upon to be reinstated as the

representation of outerwordly crisis (reproducing visual constructions similar

to colonial encounters of "contact"), but never to qualify their own concerns. In

this context, Zoe Todd and Jen Rose Smith discuss the hypervisibility of the

Arctic (Todd, 6; J.R. Smith, 158-162). Similarly, among distinct (and numerous)

Adivasi land rights movements against mining ongoing in eastern India, it is

chiefly the images of Dongria Kondh communities that are used to exoticise

ecological margins. Moreover, for philosophies built on the metaphysics of a

centre, a metropole or a symbolic universal space of human crisis, the crisis

is often read as events, as the experience of the "uncanny" (Ghosh, 30)[7] or

as marked instances defined by a state of significant visibility such as the melting

of polar icescapes. This

practise may unconsciously displace the seemingly insignificant particularities

of "localised markers" in peripheral geographies as adequate evidence of the

climate crisis.

Besides, marginalisation of Indigenous

responses to the crisis depoliticises the fact that the climate crisis in the

peripheries is the result of excesses of the Euro-American centre, not just

historically but in contemporary global industrialism (Agarwal and Narain, "Global

Warming",np). The way the Kondh songs that I discuss in this paper are linked

to the United Kingdom, for instance, is that they sing against mineral

extraction by Vedanta, a bauxite mining giant with its headquarters in London.

The capital flow from the company's profits is felt predominantly in centres of

capital and culture in the Global North, rather than outside the company walls

in southern Odisha, where the Adivasi communities are displaced. Therefore, positioning

these songs in literary studies is not simply to answer the question of why

Indigenous literatures continue to occupy particular corridors in literary

studies, a subject of continued engagement in decolonising syllabuses recently.

Attending to the voices of resident communities in these geographies in our

literary readings of the Anthropocene is to render the crisis in these

geographies visible and disrupt the inequalities and centre-peripheral binary

which global capital does not follow but insidiously maintains. Historicising

the "locality in the Anthropocene", Vineeta Damodaran writes, "challenges

planetary debates by earth scientists through a historical and political

engagement with capitalism, democracy and resource extraction and to focus on

communities in particular periods and places and specific places in the Global

South" (96).[8]

Her work in environmental history foregrounds the local and Indigenous in

eastern India, specifically Jharkhand and Odisha. I emphasise Indigenous

literary articulations as fundamental evidence of this history, given that an

account of climate vocabularies cannot be assembled outside the realm of

Indigenous literary traditions that serve as historical archives.

Literary methodology serves to

uncover metaphors and other literary devices used to describe the crisis in regional

languages and, more importantly, to help recover and restore Indigenous voices.[9] The

absence of Indigenous imaginations of the crisis in contemporary discourse is

rooted in the problem of the absence of Indigenous literary voices. Here, I will

briefly discuss the particular absence of Adivasi literary voices. An access to

imaginations and representations of Indigeneity or "Adivasihood" of the Global

South in transnational discourse has been aided largely by subaltern studies

and postcolonial theory. However, these methods have been dominated by

caste-privileged scholars. Here, I similarly acknowledge my positionality as

one, and hence I am cautious of my voice operating within this structure. While

engaging with Adivasi voices from an institutional position in the United

Kingdom, a first introduction to understand the position of subaltern voice is

Gayatri Chakrabarti Spivak's essay "Can the Subaltern Speak?". Similarly, the

first primer to "Adivasi literatures" are the representational narratives of

Gopinath Mohanty and Mahashweta Devi. These texts are representative of the

textual decolonisation of the dominant canon and decolonised syllabuses. In

postcolonial studies, they occupy the positions of canonical literary and

theoretical treatises. Both accounts are crucial to challenge the continued

Eurocentrism of institutional discourse that I discussed earlier and do not in

themselves form the primary problematic. The concern, however, is that Adivasi literatures

are accessed, but from sources twice-removed from the original source. In transnational

literary studies, these texts become exemplary to situating Adivasi concerns.

In the process, they have marginalised Adivasi voices and positionalities. It

further shifts focus from Adivasi agency for the (now) indispensable necessity

to complicate the postcolonial Indian nation state, and its virulent Hindu

nationalism, where the idea of the "Adivasi" is

employed in maintaining the myth of the Hindu nation at the same time as

Adivasi sovereignty is deemed as a threat to Hindu nationalism.

Subaltern Adivasi histories have

been recovered to challenge the mainstream nationalist narrative. Still,

literary history and criticism has often failed to read into the disquiet within

Adivasi literary tradition and the complexities they voice through

self-definitions not only in the "self-governing literatures" (Wright "The

Ancient Library", np), but also in the interface of folklore collections and

colonial archives. Though literary studies (global and national) can claim the

sheer diversity of literatures across several Adivasi languages and literary

forms, and scarcity of translations to access these literatures, it is in fact

the continued marginalisation of Adivasi literatures as literary that

precludes impetus to translation, transmission, and publication. Santhali

writer and activist Bandana Tete critiques the Brahminical Hindi literary tradition

that has dominated vernacular literary culture. She claims that not only has this

literary tradition acted as the central voice in Indian "national" literatures

but also exercised control on publications and publishing houses. She writes

that "their" incompetence in finding Adivasi women's writing should not be an

excuse (here, I translate and summarise) "to elide the very essential existence

of women in the history of poetry writing" (Tete 7). Recovering Adivasi

voices in literary reading, therefore, centres the "self-governing" Adivasi

literary landscape where the subaltern no longer remains the subaltern

but embodies sovereignty.

Recovering

voice recovers vital evidence. Here, I return to my previous point about

Indigenous voices on the crisis. Literary

methodology can serve to unravel overlooked markers of crisis already felt

in peripheral geographies.

These imaginations present "localised markers" and the local impact on

non-humans. They do not necessarily intimate an apocalyptic imagination of

sudden colossal change, but rather direct attention to long-term changes in

ecology which frequently go unarchived in dominant cultures of documentation. It

directs us to question what is considered as legitimate evidence of the

crisis? Heather Davis and Zoe Todd discuss the language of evidence in

documenting anthropogenic impact. They discuss that evidence, especially the

one measured and conceptualized in scientific disciplines, does not necessarily

accommodate the possibilities of imagining evidence from material and embodied

community histories. In order to theorise the Anthropocene from land-based

philosophies, the writers provide methods to understand the particular place

that the non-human occupies in Indigenous knowledge systems (Davis and Todd,

767). [10]

On discussing personal narratives of seeing "a flash of a school of minnows"

and memories of growing up beside the prairie lakes as "tracers" to the way

they see ecological change, Todd argues that these "fleshy philosophies and

fleshy bodies are precisely the stakes of the Anthropocene" (767). Documenting

the "school of minnows" as the "tracer", here, serves to connect the material

and the epistemological. The writers communicate that not only has the

Anthropocene aggravated "existing social inequalities and power structures",

but it has separated people from the land/material (here, minnows in the

prairie lake) "with which they and their language, laws and knowledge systems

are entwined". The argument made here is not to pit the scientific and the social

to serve as evidentiary for the climate crisis; making binaries of these

categories is not a productive endeavour in either discipline. Rather, the

argument is to reveal that the crisis has profound political and social

repercussions within communities. The crisis is not impersonal and distant but

is keenly felt and interpreted by different species—human and non-human.

And these localised markers and personal memories of climate change likewise

need documentation.

As Ghosh notes briefly in

relation to people of the Sunderbans and Yukon, some communities in fact "never

lost this awareness" of "non-human interlocuters" (63-64). How, then, to

recuperate these imaginations which would serve as evidence to the crisis? An

emerging glossary in contemporary English language has served to accommodate

the climate breakdown, the "realization" of living in the epoch of the "Anthropocene",

and ways to comprehend the dissimilar magnitudes of historical and geological

timescales. Likewise, Indigenous languages have imprinted in them the distinct

registers of historical processes markedly felt as a "crisis", in vocabularies

that we do not yet centre in climate studies. Apart from the meteorological terms

of analysis that are required to write climate history, it is imperative to

foreground recurring terms and popular vocabularies that have served as means

to communicate similar phenomena. Given that these vocabularies might not

necessarily be historically archived, literary studies need to trace the

occurrence of terms that have echoed increasing anthropogenic impact. Although it

needs acknowledging that these connections may not occur as direct lines of

causation, of exact historical co-relation between events and literary

responses (in songs, oral narratives, or written literature). Historicising

climate resistance vocabulary necessitates literary criticism to ponder on and imagine

a potential map of literary traces from significant historical junctures to ascertain

a consciousness that is often absent or erased given that these have been

minority histories and voices. As has already been reasoned in the context of

South Asia, Native American oral history, and Australian Indigenous

literatures, among others, Indigenous ways of historiography and archiving

memory span across literary genres (Skaria; Rao et al; Womack; Benterrak et al;

Wright). While a significant scale of resources is available for

history-writing and literary studies for dominant communities (given they have

dominated ownership and access to knowledge as settler colonisers or caste

hierarchies in India), Adivasi histories and vocabularies from the nineteenth

and early twentieth centuries exist between the crevices of anthropological

constructions, and erasures. This makes it all the more important for literary

studies to create interpretative spaces. In these spaces, metaphors and

repetitions of particular words can be imbued with meaning, to assemble a

repository that restores gaps in the deliberations around the crisis.

Language, additionally, is crucial

to comprehend the loss of the material that has occupied an other-than-human temporality.

Cultivation of attention to perceive deep time in the minute details of the

local is facilitated by the metaphorical function of language. Robin Wall

Kimmerer, the Potawatomi plant scientist and writer, calls such a function a "grammar

of animacy" (Braiding 48). She writes that, along with being a plant

scientist, she is a poet: "the world speaks to me in metaphor" (29). She

theorises that a "profound error in grammar" in scientific conceptions of the

natural world (and consequentially of the climate crisis) is because of "a

grave loss in translation from [N]ative languages" (48). To understand a bay,

a non-human element of the landscape, she retrieves the word from its

containment as a noun form in English. She explains that the Potawatomi word

for a bay, wiikwegamaa, is a verb that assigns agency to the

non-human feature of landscape: "To be a bay" is the bay making its

presence known (55). The other elements around it, the water or "cedar roots

and a flock of baby mergansers" (55) variously interact with the bay as animate

entities striking alignment through their specific channels of communication.[11]

In the final section of this paper, I discuss the poetry of Bhagban Majhi and

Dambu Praska, remembering this "grammar of animacy" (48). Together with

providing a linguistic pathway to understand the deep time of non-human

elements, [12]

this "grammar" is committed to an

understanding of political inequality.[13]

Indigenous poetry provides rich sites that amalgamate a political critique of

colonialism alongside cognitive tools to situate the non-human.

Through a literary reading,

therefore, I frame jal, jangal, jameen as climate vocabularies, in the

next section. The plural form of "vocabularies" used in this paper is to

encompass the translations and transmutations of jal, jangal, jameen in

several Adivasi and other vernaculars. Here, I will briefly raise the question

about the choice of using "climate" in climate vocabularies and climate

consciousness, as opposed to an ecological or environmental consciousness. Wider

awareness about changing earth systems over geological time-scales and their impact

on humans globally, is arguably recent. The global day-to-day acceptance of

climate as a planetary system as opposed to regional weather regimes is also

contemporary. The Anthropocene, similarly, is a recently coined (English) term

to define an epoch where humans have influence at a geological scale. More than

a definitive stance on when a climate consciousness of the current form of the

crisis begins, I would like to maintain an open-ended one. This might allow a

space for rethinking and robust gathering of vocabularies from a longer time-period

that informs current understanding. As I discuss in the next section, work on

climate history and extreme weather events was ongoing in research and

scholarship much before it grew into common parlance. Indigenous populations

were not just affected by local ecological phenomena, but by these events which

we currently study as global climatic occurrences (ENSO). Moreover, while the

use of "climate" in the humanities, more than ecological or environmental, refers

to a recent and specific conglomeration of ideas on planetary phenomena, it

remains one which is bound to an understanding in scholarship within the

dominant English language.

To use the word climate is thus

to acknowledge the many other iterations and interpretations of the term in

Indigenous languages that are similar and may contribute to a broader social and

historical understanding of the term and phenomenon as we use and know it today.

Consider, for instance, Rachel Qitsualik's (Inuk, Scottish, Cree) and Keavy

Martin's definition of Sila. In its varied use in Inuit languages, Sila

encompasses a material understanding of climate as tangible phenomena.

Here, climate is a combined influence of land, air, and sky and a

community-held belief in its separate presence and animacy (Todd 5; Martin

4-5). Of a similar iteration, Inupiaq anthropologist Herbert Anungazuk called

some of the "old ways of weather and ice predictions" as "ilisimiksaavut—'what

we must know'" (Anungazuk, 101). In the context of Australian country, Nyigina

elder Paddy Roe evokes the word liyan which approximates as an "intuition"

or "life force of a place" that "enables people to feel their environment" (Roe,

qtd. in Morissey and Healy 229). It is in this glossary, I choose to examine

the occurrence of jal, jangal, jameen. Finally, the focus on the local

is to question continued Eurocentrism in climate studies and to centre

marginalised histories. However, an either/or between the local and the

planetary is limiting to a deeper reflection on the crisis. It tends to streamline

the complex understanding of both which Indigenous thinkers and artists have

sought to express in their literatures. Thus, it is with care that these

vocabularies need to be read and situated. A simplified leaning to unearth the "precolonial"

as the site for "alternative" knowledge as an isolated framework to

study the crisis can do more harm to decolonial endeavours. Such a method often

tends to exoticize rather than historicise key Indigenous understanding on the

crisis. It frames it as a "return" to a past of Indigenous knowledge systems,

rendering them stagnant as opposed to an evolving, continuous process of

interacting intellectual histories. Climate vocabularies, therefore, are an

invitation to seek the fine print of the crisis registered in literary

metaphors; this reading can enrich our knowledge of the crisis as it unfolds

today.

I

re-iterate, here, the need to access Indigenous voices in archived literatures.

This is emblematic of a larger problem while reading oral traditions, origin

myths, and archived Indigenous literatures, which come to the researcher

removed from their context and burdened with the constructions created in

colonial/upper-caste translation or ethnographic work. However, this does not

discourage readings of these texts. Adivasi literary archives open to a

significant world of possibilities when read in conversation with other

Indigenous writers and when studied with the methodologies formulated by

Indigenous theorists. Creek historian Craig S. Womack critiques the ongoing "problem"

of Native American texts (oral, performative, and written) characterized as "lost

in translation" (64) as opposed to translations from other dominant cultures; this,

he argues, postpones contextual and political analysis. Therefore, rather than a rejection of

early twentieth-century archives of Adivasi songs and myths, transcribed and

translated by colonial anthropologists and ethnographers, I read them as texts

operating within the milieus of their historical encounters and responding to

colonial methods of collections and archives. Being supported by methodologies

of literary reading provided by Womack and Muecke among others helps recover

Indigenous voice from the aporias around oral texts and translations built by

structural categories in colonial ethnography. This allows for the text's

reinstatement as political and presents possibilities for a "literary repatriation"

(Unaipon xliii).

II.

Jal, Jangal,

Jameen as Climate Vocabularies

The climate history of

Odisha is largely anthropogenic. Mineral extraction of the last few decades has

exacerbated the crisis on ecologies already fragile from a history of

exploitation of jal, jangal, jameen.[14]

Odisha—which in recent years is known as a cyclone-prone region—was infamously called marudi anchala or Land of Droughts. El Niño and

the Southern Oscillation (ENSO) occurrences caused meteorological dry periods

in the region. In addition, hydrological droughts[15]

significantly increased from radical changes in land use during the nineteenth

century, especially with the growth of commercialized agriculture and

deforestation. The time-period in Odisha's history that is primarily remembered

for its scarcity is also, ironically, a time when land use became largely

agrarian to increase revenue. Prior to 1850, upper-caste communities from the

plains of Sambalpur and Raipur started migrating for settled agriculture in the

districts of Kalahandi, Bolangir, and Koraput (KBK) (Pati Situating 101-102),

areas with the highest population of resident Adivasi communities in eastern

India. Grain shortages, due to changes in the crop cycles (ibid), also began during

this period, leading to resistance by Adivasi communities. The scarcities

become acute in the 1860s. J. P Das, in his historical narrative A Time Elsewhere

(2009), translated by Jatin Nayak, earlier published in Oriya as Desa

Kala Patra (1992), describes the years leading up to

1866, the year of the deadly Odisha famine. This was a decade of paradoxes for

the region. The reigning leaders and litterateurs like Madhusudan Das, Fakir

Mohan Senapati, and Radhanath Ray eagerly awaited Odisha's first printing press.

An independent press would establish the eminence of Oriya literature and, in

turn, Oriya nationalism, rescuing it from the colonial impact of Bengal. At the

same time, houses were steadily declaring grain scarcity. The famine ravaged. Market

prices soared, grain was exported to the empire, stocked rice controlled by

zamindars and colonial officers along with imported relief was stranded in

ports and delayed reaching the famished (Das ch.2) The drought and the Great

Famine of Odisha in 1866 killed a million people, nearly a third of the

population of Odisha (Odisha division of Kolkatta presidency) at the time,

leading to vast demographic and geographical change (Mohanty, 608).

Following this year, the famines of 1876-79

severely impacted east-Indian geographies, with a total of 50 million deaths

across India (Grove, 144). This was a severity similar to the 48-55 million

deaths between 1492 and 1610 because of disease and enslavement (Lewis and

Maslin, 75) that is commonly considered as the beginning of the crisis for

American Indigenous communities. The Odisha Famine of 1866 served as a warning

to the famines that followed. Henry Blanford was appointed as imperial

meteorological officer to the government of India on the recommendation of the

1866 Orissa Famine Commission to study the failure of monsoons and the

persistence of droughts (Davis, 217). Climate studies on east-Indian geography were

supported since agricultural failure directly impacted the empire. Richard

Grove discusses this history: severe droughts and shortage of rainfall of the

1870s and 1890s have been determined to be a result of ENSO, extreme warm

events that have a global climatic impact leading to similar drought conditions

in South Asia, Australia, Southern Africa, the Caribbean, and Mexico (124).

However, as he mentions, climate studies had already been conducted since the

1700s to record the periodicity of droughts and study the reason for long-term

weather conditions. Colonial researchers like William Roxbourgh, who had been

collecting data on tropical meteorology, had identified the relationship

between climate change and recurrent famines as relating to colonial impact

(even leading to afforestation efforts in the nineteenth century).

Global meteorological surveys and

climate studies were, yet again, within a limited realm of knowledge controlled

by the empire and dominant communities. It could be argued that the scientific

conception of a world climate system and its effect to generate conditions of

crisis did not yet exist as community knowledge (or it requires further search).

However, the severity of drought and famine conditions as a result of these

climatic events—and the exploitation of jal, jangal, jameen to

facilitate revenue-generation for the British empire—framed the climate

vocabulary of eastern India. Anthropogenic impacts on these geographies (the jal,

jangal, jameen of Adivasi communities) had rendered them incapable to

cushion the force of periodically occurring calamities. More than a singular "event",

the year of 1866 and the following famines have been read as part of a "process"

that was a direct continuation of land-loss to zamindars (landlords) and

commercialized grain trade without adequate returns to the farmers (Mohanty

609).[16]

The easy accumulation of jameen

(land) was aided by the Land Acquisition Act of 1894. Changes in the use of jameen

meant that Adivasi communities were assimilated into the caste system, serving

under highly oppressive forms of bonded labour like bethi and gothi,

systems in which existence was defined by a perpetual state of debt and

enslavement to the landlord. A significant number of Adivasi communities

migrated to forest tracts, given the increase in agricultural settlers on their

land. However, the India Forest Act 1865, designed specifically to clear

forests for railways, and later the Forest Act of 1878, heralded the "reserved"

forests to increase timber production and to grow more cash crops such as jute

and indigo. This act prohibited use of the jangal and curbed Adivasi

agricultural practices such as bewar, jhum, or podu chasa,

various forms of shifting cultivation practiced on forest slopes. The jameen

and jangal (and jal), the non-humans that sustained Adivasi

communities, were appropriated as resources. Furthermore, they were regimented

to disallow interconnected living. The onset of fragility of east-Indian

geographies was brought about by an accretion of control on jal, jangal,

jameen. This lent itself to a lived sense of "crisis", owing to fractured

ecologies and growing inequalities felt in the apocalyptic proportions of the

century's famines which Mike Davis describes as "late Victorian Holocausts"

that formed the "Third World" (see Davis). Having lost jal, jangal, jameen,

the once-princely communities became destitute within half a century. When the

colonial government imported "poorhouses", Davis quotes a missionary document

as saying, "Confinement was especially unbearable to the tribal people, like Gonds

and Baigas, whom one missionary claimed, "would sooner die in their homes or

their native jungle, than submit to the restraint of a government Poor House'" (Davis,

147). He claims that such antipathy was less about confinement and more

revealing of the diet the poor houses served: flour and salt. For Adivasi

communities, these decades prefigured a dire future. Their essential organizing

ecologies were not only colonized, unresponsive, and crumbling, but they had to

depend on the apocalyptic measures of the colonizer for survival.

While these early instances of a

seismic shift in eastern India may have found utterance archived in Adivasi

oral traditions of the nineteenth century, we may have lost access to them in

transmission. Moreover, apart from the climatic constants of famines and

droughts, the micro-climates of eastern India were heavily altered with the

beginning of mineral extraction that exacerbated ongoing concerns of land

dispossession. By the end of the nineteenth century, there were increased

invasions on eastern Indian landscape through mining for mica, slate, and

chromite (Mishra "From Tribal to", 30). We see articulations of mining activity

in myths transcribed by Verrier Elwin in Tribal Myths of Orissa

collected in the 1940s-50s, and we can assume that these songs had already been

in circulation in popular memory before these decades.[17]

One of the Bonda myths from Koraput reads:

There

was no money in the old days. But after Mahaprabhu gave the kingdom of

Simapatna to Sima Raja and Sima Rani, a government office was made to deal with

everything [...] One day Mahaprabhu took Sima Rani to the Silver Mountain and

showed her great heaps of silver. "That is silver", he said [...] Then he took

her to the Gold Mountain and showed her great heaps of gold [...] Then he took

her to the Copper Mountain and showed her great heaps of copper. (Elwin Tribal

Myths, 561)

The myth not only

demonstrates land transactions, as Sima Raja and Sima Rani are "given" the

kingdom, but also the entry of a third entity that carried out these

transactions, "the government office". That a scanning of the landscape to

determine sites for mining minerals was on-going is reflected in how Sima Rani

is "shown" these riches of the land. She subsequently mints them into coins,

signifying a transition from seeing mountains as living entities to seeing them

as capital.[18]

Such occurrences in mythical narratives coincide with increased mining in the

region. Coal and iron ore exports steadily increased with the expansion of

railways and industries in the 1880s. Tata and Sons

and the Bengal Iron and Steel Manufacturing Company started sustained mineral

extraction in 1905 (Pati Adivasis, 257). Samarendra Das and Felix

Padel explore the history of bauxite in Odisha, a sedimentary rock that has

become a site for struggle in recent movements, which I explore in the next

section. They write about how the bauxite-rich hills of Kalahandi were

documented as a resource by geological surveys carried out by T. L. Walker in

early 1900, who named the rock Khondalite, after the resident Kondh community

(Das and Padel, 58). Subsequent surveys continued through the twentieth century

until the last decade, when liberalization of the economic policies of the

1990s allowed multinational companies access to mine the hills. The mining

excesses of the last three decades further impaired an already fragile ecology,

and form a significant period in the climate history of Odisha after the decade

of 1866. Therefore, Bhagban Majhi and Dambu Praska's poetry, which I discuss in

the next section, situate the present crisis as one with a longer history.

The

radical impact on jal, jangal, jameen had been noted as a significant

climatic concern albeit in a language and scale that was localized. Jal, jangal,

jameen, apart from evoking this common climatic history for diverse Adivasi

communities, unify a common understanding of material ecology and provide a

holistic basis to "sacred"[19]

philosophies present in Adivasi knowledge systems. A recent resolution was

passed for Sarna to be accepted as a religious code which would include Adivasi

religions similar to Sarna under its fold. It was claimed that the acceptance

of Sarna as a separate religious group by the Indian government would also regulate

"resource politics" (perhaps, in favour of the Adivasis). This rested on the

claim that religious identity of Adivasis is founded on the natural resources

of jal, jangal, jameen (Alam "Why the Sarna Code", np). These intricate

systems that combine a philosophy of ecological interdependence, religion, and

literary tradition[20] have often

evaded colonial classifications,[21] those

classifications that presupposed Adivasi "primitivity" and intellectual

inferiority. Perhaps for this reason, the archival transcriptions of

anthropologists like Verrier Elwin and Shamrao Hilvale, among others, carry the

warnings of crisis, without further consideration of the predicament

articulated by Adivasi communities. The loss of the jangal was

registered as a "calamity" in a song transcribed by Elwin and Hilvale in the

1930s and 1940s:

Such

a calamity had never been before!

Some

he beats, some he catches by the ear,

Some

he drives out of the village.

He

robs us of our axes, he robs us of our jungle.

He

beats the Gond; he drives the Baiga and Baigin from their jungle. (Elwin The

Baiga, 130)

Here, the "calamity" is described as

unforeseen and of a form not encountered previously. The song proclaims that

the hand of colonial power and human intrusion on the jangal practiced

excesses that even surpassed the accustomed bearings and regularity of a

natural "calamity". Localised resistances to counter the increased control on jal,

jangal, jameen were ongoing since the early nineteenth century. It was

Birsa Munda's movement, or ulgulan in Chottanagpur province in the 1890s,

that provided an impetus for jal, jangal, jameen to become a "common

organizing force" for Adivasi communities. Birsa specifically demanded the

re-instatement of Khuntkatti system, which was based on collective

ownership of land and forests by Adivasi communities. In his reading of Gond

history, Akash Poyam claims that the slogan "jal, jangal, jameen"

as a unified call for protection was later coined by a forgotten Gond Adivasi

leader from Telangana, Komaram Bheem ("Gondwana", 131). Sharing "common cause" with Birsa Munda to resist against

exacting taxes and oppression by landlords, Bheem used the call during the

Gondwana movement against the Nizam government of Hyderabad to demand complete

land and forest rights. Poyam contends that the vocabulary of jal, jangal,

jameen was specific in its concern to establish Gond sovereignty and

autonomy over jal, jangal, jameen ("Komaram Bheem"). Contemporary discourse on climate change and environmental

conservation, therefore, cannot be studied separately from the long history of

Adivasi movements for land rights and sovereignty. These contexts reveal

Adivasi vocabularies that signal structural inequalities which makes them more

vulnerable to the current crisis.

The crisis of the human, especially

after the theorization of the Anthropocene in geology in 2000 in dominant

Euro-American centres, has critical precursors in the peripheries. For Adivasi

communities, the crisis of human and non-human existence was anticipated in the

calls to protect jal, jangal, jameen. Jal, jangal, jameen rhymed

and echoed to sustain material and epistemological continuity after the

calamitous impact of resource exploitation during the nineteenth century.

Although it is beyond the scope of this paper to access further literary

readings of archives and transcribed myths and songs, my intention is to

revisit the recurrence of jal, jangal, jameen and read them as climate

vocabularies. These vocabularies are recurrent because they archive a

generational memory of lived crisis during climatic occurrences (such as

droughts and famines) and anthropogenic impact on non-humans around which

Adivasi philosophies are organized. The political consciousness of Adivasi

movements on land rights that is deeply committed to the indispensability of

protective measures for jal, jangal, jameen is indeed contemporary

climate discourse prefigured. To this climate history and genealogy of

resistance, the songs of Bhagban Majhi and Dambu Praska bear allegiance. Their

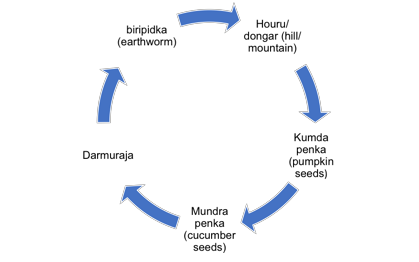

invocations of the mountain, earthworm, and seeds present vital evidence of the

enmeshed ecology of jal, jangal, jameen particular to their contexts in

south Odisha.

III.

Of Mountains and Earthworms

Bhagban Majhi, a Kondh

singer and leader from Kucheipadar village (Rayagada district in southern

Odisha), was one of the leading voices of Kashipur resistance against bauxite

mining by Utkal Alumina International Limited (UAIL), and later, Aditya Birla.[22]

The movement began in the early 1990s and continued for over two decades, a momentum

of resistance that was later carried forward by the Dongria Kondh community to

oppose Vedanta in Niyamgiri. Despite a sustained struggle by the Kondh-Paraja

community in villages around Kashipur, Aditya Birla acquired land and, in

present day, the displaced Adivasi communities live in the peripheries of the

factory walls.[23] Bhagban, as

a teenager, along with Lima Majhi, composed a number of songs (in kui and

desia, which was later adapted in Oriya and Hindi), that were widely transmitted

to unite the communities. From those specifically composed for the movement, Gaan

Chadiba Nahin (We Will Not Forsake This Land), was identified as a common

anthem in several movements against mining and forced evictions in India. Having

found utterance in a dominant language such as Hindi, with a popular video Gaon

Chodab Nahin subsequently produced by K. P. Sasi, the song acquired

pan-cultural presence. Apart from its rhyme that was predisposed to

transmission across linguistic and regional borders, Gaan Chadiba Nahin

remains one of the most subversive songs to be formulated as part of Adivasi

literary song traditions in recent decades. Bhagban's political critique is

embedded in Kondh-Paraja epistemology particular to south Odisha. His

interpretation of jal, jangal, jameen which, in this song, is articulated

as dongar-jharan-jangal-paban (mountains-waterfalls-forests-winds),

connects it to the long history of Adivasi climate consciousness.

We will not yield,

we will not give up,

no, we will not forsake this mountain.

[...]

Our hills, our companions,

our growth, our progress.

We are the children of this earth.

With folded hands,

we bow down to our earth mother.

[...]

We are the people of this earth—

we are earthworms—

mountains—streams—forests—winds—

if we forsake this earth

how shall we endure?

Worlds shall collapse,

lives will crumble, when

the pathways drown,

how will we endure?

We will be nowhere

we will be no more—

there is no hereafter—

no, we will not forsake this land. (Prakrutika,

19)

My translation is from a desia

(a pidgin variety of Oriya and Kui) transcription of the song archived in the

Kashipur movement pamphlet, Kashipur Ghosanapatra, published by Prakrutika

Sampad Surakhya Parishad (a local environmental protection committee

founded during the Kashipur movement). Here, Bhagban presents two fundamental

ideas, unnati (progress/development) and matrubhakti (love for

the mother). Matrubhakti for the mountain or dongar as the mother,

as invoked in Bhagban's song, departs from invocations of the motherland/mother-earth

in the context of Indian nationalism. Additionally, matrubhakti

linguistically may have its roots in songs composed during the Gandhamardhan

movement against Bharat Aluminum Company Limited (BALCO). In its philosophy,

however, Matrubhakti digresses from the Hindu mythical motifs that

became the driving force in Gandhamardhan. Here,

the salutation of deference bows to non-human elements. Matrubhakti is

ethical kinship with "all our relations".[24]

Matrubhakti is for the earth mother, Dharni penu. Notably,

because of this conception of mountains forming essential basis to all human–non-human

life forms, they occur invariably as gods, or kings, as entities who are

agential, in the religious beliefs prevalent in Kashipur as well as Niyamgiri.

Through a general use of dongar, Bhagban alludes to Baplamali, Kutrumali,

and Sijimali, the bauxite-rich ranges of south Odisha, which have formed "through

the alternating rhythm of rain and sun continuing every year for about 40

million years, eroding layers of feldspar and other rocks" (Das and Padel, 32).

Bhagban presents evidence of this elemental bind that sustains the ecology of

eastern India: "dongar-jharan-jangal-paban" or "mountains-waterfalls-forests-winds"

exist because of the mineral-rich mountains. The Kondh community is intricately

bound to this ecology.

His

song, consequently, offers the Kondh understanding of humans as matira poka,

or biripidika – earthworms.[25]

As part of the movement against mining, he demanded, "We ask one fundamental

question: How can we survive if our lands are taken away from us? [...] We are

earthworms. [...] What we need is stable development. We won't allow our billions

of years old water and land to go to ruin just to pander to the greed of some

officers" (qtd. in Das and Padel, 394-395). For Bhagban, notions of unnati

or development are embedded in a cosmology that has decentred the human. For dikus

(outsiders) of such a conception, his poetry conveys a radical understanding of

progress that necessitates discerning the temporalities of the earthworm and

the mountain. The "fleshy philosophy" of the earthworm opens a "pathway" to

grasp the dissimilar magnitudes of temporal perceptions that the Anthropocene

commands: the dongar of deep geological time, and the dongar as

capital in the history of mineral extraction. Kondh conceptions of the human as

biripidka or earthworm, the human as part of the elemental cosmology of

the Kucheipadar landscape, enables a comprehension of mountains as autonomous

annals of knowledge beyond their reductive quantification as "resource" for a

nation's progress. To understand the extent of irredeemable loss of the dongar

would require understanding its existence as separate from human history, with

its own annals of millennia of slow formation and evolution.

Unnati

and matrubhakti have essentially formed the ideological basis of the

Hindu nationalist state's divisive enterprise and the nation state's invasion

of Adivasi land for industrial progress. Bhagban's interpretation of these

words thus becomes crucial. He frames climate action as the political

responsibility of the present to resist complicit governments whilst having a

deep-time consciousness of the mountains, a dual task that delineates human

positionality in the Anthropocene. In his speeches and testimonies, unnati

as imagined by the Indian state and mining companies for short-term profit that

would deplete this "resource" within thirty to forty years, is juxtaposed with unnati

rooted in a comprehension of the mountain that has a profound dimension. He

asks, "Sir, what do you mean by development? Is it development to destroy these

billions of years old mountains for the profit of a few officials?" (qtd. in Das

and Padel, 10). He represents and communicates a Kondh humanism in his songs

through his interpretation of development as one that honors the human's

ethical relationship to land. "Humans as earthworms" in kinship with the

mountains orients human perception and equally counsels on the fragility of

these enmeshed interfaces. During our conversation in 2017, he presented this

thought as a "fairly basic" idea which he had attempted to convince people of

during the movement. Human impact on land is fueled by industries, and to

oppose destruction of ecologies is a universal responsibility. He said, "People

think this is for Adivasi's self-interest. This resistance is against 'loot'.

The riches of the land that is being destroyed is not of the Adivasi's alone.

The environment, sky, this is not of the Adivasi's alone. It belongs to the

living, and the living suffer. The profits are for the company" (Majhi).

Bhagban's

political thought, beside a consciousness of "humans as earthworms", poses

further questions to our belated understanding. Is the binary by which we

understand the Anthropocene in literary imagination, of geological and

historical time, adequate to comprehend the lived temporalities of non-humans?

For are not our metaphors for understanding the non-human again dependent on

the scales of human measurements and the grammar of theory? What is the

language in which to imagine scale and inhabit temporal dimensions as

earthworms and living mountains? As in several Adivasi creation stories, the

earthworms collected earth until it sufficed living beings. The dongar

is a law-making entity as much as its creation and sustenance depends on the

enterprise of the earthworms. And yet again, given the mutuality in their

relationship, can the temporality of the mountain alongside the earthworm be

imagined at all through progression or variations in scale? The dongar

and biripidka claim sovereignty on temporality, equally on the forms of

the annals they maintain. As a conduit to their claims, Bhagban Majhi's

political activism becomes critical. For young Kondh leaders of the movement,

understanding the metrics used by the company was equally important to predict

the "calamity" that mining would ensue. To thoroughly investigate the statistics

proposed by the state and the company, the "tonnes of bauxite" as opposed to a

living dongar was vital, so that Kondh ideas of progress could be

proposed and reasoned. To examine the measures of employment and education that

was promised by unnati was to ascertain whether the villages would be

direct beneficiaries or marginalised again. The annals of the earthworms and

the mountains had to be juxtaposed with metrics that stem from and accommodate

human centrality and that are estimated to have higher "pragmatic" value. As we

shall come across in the next section, the translation of Dambu Praska's song

carries a similar duality: "a measuring has begun of Leka houru" (Praska,

qtd. in Dash 2013). Praska, similarly, juxtaposes temporal scales of his origin

epic and company metrics. The elders of the village, and singers like Bhagban

Majhi, were consequently part of a philosophical struggle to grapple with the

modes of adopted languages to convey Kondh epistemologies connected to the dongar

and biripidka. This leads me to explore yet another "fleshy philosophy"

of the earthworm in Dambu Praska's epic rendition.

IV.

Of Mountains and Seeds

Listen, O elder, O brother,

the story I tell you:

this mountain is our ancestor, our Darmuraja.

This mountain is cucumbers, pumpkins, and all that was

created.

Listen, O brother, our only story.

.................

The king summons the elder brother to the feast,

the middle ones with tattered clothes,

are asked to leave—

crossing mighty rivers, the middle ones are scattered

.................

A call resounds from village to village—

assemble on the mountain—

But we shall not leave.

There, lives Darmuraja... (Praska, qtd. in Dash 2013)[26]

The late Dongria Kondh poet's song "The

Lament of Niyamraja" is rooted in the Dongria Kondh oral epical tradition. As

the jani (priest) of the community, he sings in a literary form of Kui.

The singular long-form of this rendition is archived in the video documentary

by Bhubaneswar-based filmmaker Surya Shankar Dash titled "Lament of Niyamraja".[27]

Here, my English translation is based on a recent full-text translation by Arna

Majhi (from Kui to Oriya) that has clarified the complex text of Praska and

helped bring previously unconsidered aspects of the song to light.[28]

The song was collected in the years leading up to the village council hearings

held in Niyamgiri by the Supreme Court of India in 2013. India's apex court

demanded legitimate reasons why the Dongria Kondh community opposed Vedanta's

proposal to mine bauxite on their hills. One afternoon during the movement,

Dash asked Dambu Praska that, if Praska was called by the state to a hearing,

what would he render as a reply on behalf of his community? In reply to Dash's

question, Dambu Praska sang "The Lament of Niyamraja", presenting evidence of

legal ownership of the hills: the intimate knowledge of penka (seeds)

which for him are "the stakes of the Anthropocene" (Davis and Todd, 767).

Through metaphors in his poetry, he communicates legal conceptions embedded in penka

or seeds of the pumpkin (kumda penka) and cucumber (mundra penka).

In his song, the Dongria Kondh cosmology is represented as having its origins

from non-human elements like the earth and its earthworms (biripidka), as

well as the sky, who is called Darmuraja, the god who transmits this law and

knowledge.

Darmuraja, also known as Dharmaraja or

Niyamraja (King of Law), is believed to be an ancestor, an animate entity who

holds a religious position and is resident on the hills of Niyamgiri. The name "Niyamgiri"

itself suggests why it is essential to read this song through the philosophies

of the non-human articulated in Dongria Kondh mythology. "Niyamgiri", as the

name of the hill of Darmuraja, might have been a Sankritised import: giri

means hill, niyam means law in Oriya and some other Indo-Aryan

languages. It is unclear when the words may have entered Dongria Kondh

vocabulary. It is worth pondering with some skepticism whether it is a recent

import or a result of interactions with dominant traditions like Oriya, Telugu,

and Hindi, among others, during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries or even

earlier. Therefore, contrary to what is widely believed in non-Indigenous

readings of Niyamgiri, that Niyamgiri is the "Mountain of Law", with "Niyamraja"

or "Dharmaraja" presiding as the "King of Law", might be our error in

translation or an idea in Dongria Kondh mythology that has grown out of linguistic

adaptation. Dharma is a Sanskrit term for "just action" or "duty", whereas

Darmuraja refers to the Dongria Kondh "ancestor", who decides the law of

the community. The law that Dambu Praska sings about is distinctive and not

related to "dharma" in Hindu traditions. In other words, Dambu Praska is

potentially singing about the law embedded in the seeds of the pumpkin and the

cucumber.

Praska

braids the origin myth of the Dongria Kondhs with the narration of present-day

call to a court hearing. He speaks through numerous voices in a tense

arrangement that alternatively straddles the temporalities of the origin myth

and the present day, where the mythical elder brother of Darmuraja, called to

the king's court to decide on the proposed settlements of their community,

overlaps with the Dongria Kondh villager called to a state hearing. Both, the

brother and the villager, are asked the same riddle:

How many seeds in a pumpkin?

How many seeds in a cucumber?

How many shall sprout and how many are hollow? (Praska, qtd.

in Dash 2013).

Dambu Praska's song

performs a struggle to answer the riddle of seeds, an answer that would form

communal evidence of belonging to their hills. At one point, Darmuraja sits

beside him to offer answers through a secret understanding, an answer Dambu

Praska does not reveal to us, the listeners. Praska's metaphorical use of the

riddle of seeds forms the basis of Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK)[29]

to judge those seeds (nida penka) which would yield a healthy crop, a

local knowledge passed down through generations in the form of a riddle. Traditional

knowledge of ownership is often guarded and closed to non-members of the community—Darmuraja, the King of Law, offers the knowledge to Praska and not the

listener. That is why Dambu Praska sings that both acts, of sharing and denial

of this "sacred" knowledge, threaten him. On the one hand, he cannot break his

community's rules of intellectual property. On the other, withholding this

proof of ownership would displace his community. At one point, the narrator in

the song denies seeds that are offered to him in order to protect their hills.

Here, the penka or the seeds become an allusion to non-Indigenous seed

varieties that were introduced on Adivasi land promising a high yield, but

which were essentially seed varieties that yield monocrops and are not suitable

for cyclical sustainable production.

Robin

Wall Kimmerer, similarly, writes of corn and essential Indigenous epistemology

and history associated with varieties of the crop that has been deemed as "primitive"

by colonial settlers. The industrial production of corn is "waste producing",

she writes, far removed from the relationship between maize and human as

planted and consumed within an "honor system": "[The]

human and the plant are linked as co-creators; humans are midwives to this

creation, not masters. The plant innovates and the people nurture and direct

that creativity." ("Corn tastes better", np). When Dambu

Praska similarly rejects the seeds that are offered to him in a "pouch", a non-Indigenous

variety for a high yield, it is his way of maintaining the Dongria Kondh "honor

system" for seeds indigenous to the hills. The hollow seeds (hatun) also

suggest the history of settlements by colonial and upper-caste communities in

southern Odisha since the nineteenth century, that I discussed earlier in this

paper. It is Dongria Kondh women who are the "guardians of seeds" (Jena "Tribal

Priestesses", np). Dongria Kondh

priestesses conduct a ritual for the collection and protection of indigenous

millet seed varieties that are in decline on the slopes of the hills.

Travelling by foot to other villages, the women request seeds to be accumulated

and sown for harvest. As reported on Vikalp Sangam, these travels reveal

not only vanishing millet seed varieties but also the sheer diversity of

indigenous seeds sown as opposed to monocropping: Dasara Kadraka, a bejuni

(priestess) from Kadaraguma village, cites the existence of thirty millet seed

varieties from the hill alone that are endangered ("Tribal Priestesses").

The

poetic repetition of seeds, the apparently simplistic and straightforward

listing of vegetables and grain, are evidentiary of sustainable practices

embedded in complex knowledge systems. The question of the number of seeds in a

cucumber, the materials of pumpkins, fruits, and grains that Darmuraja

provides, is the vital materiality that determines Dongria Kondh law and

survival. This relationship that binds Niyamgiri's ecology to the Dongria Kondh

community stands threatened in the Anthropocene. Consequently, invocations of

vegetal produce of Niyamgiri were a recurrence in the oral testimonies of

Dongria Kondh villagers presented to the Supreme Court of India to protect Niyamgiri

from bauxite mining. Dambu Praska, similarly, comments on the incoming

dispossession by the mining industry. He laments that the answer to the riddle

of the seeds is ultimately irrelevant if the land is threatened:

Seven days in the sun,

the

seeds of the pumpkin and cucumber dry up.

Listen,

O brother,

with

the sunrise, the earth warms, the mounds crumble—

the mountains grow muddy,

flow murky in the streams—

know

this, O brother,

a

measuring has begun of Leka houru.

Tell

me, O brother,

how

many seeds of the pumpkin are hollow?

how

many will sprout?

Here are nine pouches of pumpkin seeds,

here are nine pouches of cucumber seeds—

if

the land is lost, how would seeds matter? (Praska, qtd. in Dash 2013).

Praska

conveys a disillusionment with the government hearing. The Supreme Court

hearing was limited to only a few villages in Niyamgiri. By then, continued

industrial mining (more regularly since the 1990s) had already displaced

several Adivasi communities and destroyed the ecology of the neighboring hills

and villages in south Odisha. His image of muddy mountain streams evokes the

image of the toxic industrial mud ponds constructed by the company. Vedanta

alumina refinery not only consumed water that forms perennial streams of the Niyamgiri

hills, but also constructed an ash pond at the mouth of Vamsadhara River. The

river and streams on the mountains were polluted, rendering them unusable for

human consumption. Praska is aware of the ongoing devastation to their hills

and performs a series of denials towards the end of the song. He denies the

offer of seeds, buffaloes, and mangoes, metaphorical suggestions to the

material gains that the company and state offered in the name of "development"

and progress. The narrative voice in the song realizes and communicates the

indispensability of the dongar. Similar to Bhagban Majhi, Praska

communicates that mining their dongar would herald a breakdown,

destroying the slow and prolonged elemental bind of the mineral that has formed

the ecology of eastern India. The continuity of seeds, and consequently of his

community depends on the continuity of the mountain.

Conclusion:

They cannot tolerate the existence of

trees

for the roots demand land. (Kerketta,

168)

In a visionary couplet written

in Hindi, in her second anthology Jadon Ki Jameen (Land of the Roots),

Oraon poet Jacinta Kerketta engraves the existential "stakes of the

Anthropocene" (David and Todd, 767). As the titular poem to this anthology, a

two-line afterword that appears on the last page, she says that the reason they

cannot tolerate the presence of trees is because the roots demand jameen

(land). This form of non-human need is unimaginable and therefore

unaccommodated within human systems of legality and ethical practice. In this

couplet, she effectively articulates that to comprehend our present crisis

necessitates re-formulating the question of land rights, evoked here as the

rights of the land.

Through

a literary reading, I situated the recurrence of jal, jangal, jameen as

climate vocabularies to explore the Adivasi literary tradition's response to the

climate crisis. The paper was limited to the context of east-Indian

geographies. What are the other possibilities of imagining climate

vocabularies, and how will these literary readings support work on

micro-histories of particular geographies and documentation of specific Adivasi

philosophies? Similar to the "fleshy philosophies" of earthworms and seeds,

present in the songs of Dambu Praska and Bhagban Majhi, what are the ways to

archive and read similar connections to the material and vegetal? This further

raises the question of what are the various forms that climate vocabularies can

take in different Indigenous traditions and languages? In a paper titled "Inventing Climate Consciousness in Igbo Oral

Repertoire: An Analysis of mmanu eji eri okwu and Selected

Eco-Proverbs" by Dr. Chinonye C. Ekwueme-Ugwu and Anya Ude Egwu, the two Nigerian writers

present a climate consciousness embedded in Igbo proverbs. Similarly, Nicole

Furtado's evocation of "Ea", a concept stemming from Native Hawaiian

epistemology, informs the climate vocabularies framework.[30]

In the panel discussion titled "Climate Change,

Infrastructure and Adivasi Knowledge", panelists Akash Poyam, M. Yuvan, Archana

Soreng, and Raile R. Ziipao shared some of their ongoing documentation of

Indigenous knowledge traditions, ecological vocabularies, and sustainable

practices (Poyam, Soreng, et al.). These methods—for instance, M.

Yuvan's Instagram handle titled "A Naturalist's Column"—are innovative

archives and a necessary glossary for ecological education. Similar work can help uncover literary recurrences

that have served as a "common organising concept" (Todd, 5-6) in diverse

contexts and languages.

I

hope a transnational glossary on climate vocabularies can channel further

comparative work that connects the climate histories of India with settler

colonial nations, and Indigenous literary responses in the respective contexts.

Similar to India, ENSO occurrences have impacted Australian geographies

resulting in severe drought conditions in the nineteenth century. Settler

colonialism's lasting impact on North American and Australian land through

forced removals, disease, and genocide radically altered ecologies. The global

industrial complex further impacts Indigenous communities in all three

contexts. The raging bushfires of Australia in 2019, the wildfires of

California in 2020, and the recent forest fires on the Similipal reserve,

eastern India, in 2021 are some of the many symptoms of insurgent eco-systems.

Here, Indigenous communities are affected by climate change and ironically held

responsible. In India, the conservation narrative excludes Indigenous

participation and sustainable practices and penalises Indigenous communities

for environmental encroachments on their own land. Adivasi peoples are

displaced to "protect" wildlife and habitats. Kharia climate activist Archana Soreng,

therefore, demands that Adivasi communities lead the narrative and efforts on

conservation, rather than be made "victims" (Poyam, Soreng, et al.). Forthcoming

discourse on climate, conservation, and the pandemic may need to reflect on the

role of authoritarian nationalism and racism in abetting already fragile

conditions. Indigeneity and land rights of Adivasi communities are oppositional

to the Hindu nation and aligned corporate and industrial interests. Here,

Adivasi and other minority communities become dispensable bodies in their lands

as well as in urban centres where they work as migrant labourers. The exodus of

migrants from urban metropoles following the Indian state's overnight lockdown

during the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 was an authoritarian measure. In so far as

the pandemic is indicative of the climate emergency, the exodus was also a

climate-induced displacement.[31]

How to rethink and safeguard Indigenous climate justice in authoritarian

nation-states? This concern is not limited to the Hindu nationalist state. Appropriations

of Indigeneity in Europe and Britain has led a rise in xenophobia claiming

indigeneity of the "original white" population. Claiming such indigeneity, the

Far Right draws a dangerous analogy between immigration of minority populations

to UK and colonialism in settler nations.[32]

This ideology can influence conservative anti-immigration policies. At a time

when climate-induced displacements and violence within authoritarian regimes of

the Global South render Indigenous and minority populations homeless, these

policies, if realized, will deprive alternatives of safety to climate refugees.

Acknowledgements:

I acknowledge the contemporary Adivasi writers and

communities from Odisha and India, and those who have generously informed ideas

and inspired this work: Arna Majhi, Salu Majhi, Bhagban Majhi, Anchala, and Rajkumar

Sunani, to name a few. Some invaluable online presences that have informed this

paper: Adivasi Resurgence, Adivasi Lives Matter, Video

Republic, People's Archive of Rural India (PARI), and Vikalp

Sangam. This research was made possible by discussions with Saroj Mohanty,

Rabi Pradhan, Sudhir Pattnaik, Sudhir Sahu, Surya Shankar Dash, Nigamananda

Sarangi, Ranjana Padhi, Ruby Hembrom, Devidas Mishra, Kedar Mishra, and many

others. The paper is significantly informed by presentations, discussions, and

ideas emerging from the Climate Fictions/Indigenous Studies Conference

(2020). I thank the presenters and my co-convenors. Equally, it is informed by

an online panel discussion on "Climate Change, Infrastructure and

Adivasi Knowledge: Perspectives from India" (2020). I am grateful to the convenors,

and speakers Archana Soreng, Akash Poyam, M.Yuvan, and Raile Rocky Ziipao. I

thank my supervisor, Priyamvada Gopal, and my doctoral examiners, Chadwick

Allen and Robert Macfarlane, for their invaluable feedback and encouragement.